a computer tyranny

and

an invasion from mars!

the

colossus

trilogy

a near-future epic

by d f jones

Domination by an Artificial Intelligence, when expertly portrayed, hits a jackpot of broad-daylight thrills.

clear and present heebie-jeebies

Stid: By "Broad-daylight thrills" you mean, I take it, that sf can give us a rational buzz, distinct from the dreamier awe we get when reading edgier, twilit, supernatural stuff.

Zendexor: Rationality sounds boring, but you seem to get the point here. In really good sf, rationality, not in itself but in its implications, builds wonder. And in tune with the modern myth of Frankenstein, we can expect something special from an AI saga. We can hope that it will explore those above-board shudders which arise not from utter alienage, nor from supernaturalism, but from a wrongness in the human spirit....

Stid: ...Because, in a story, when an AI goes wrong, it's really our fault. We built the thing.

Zendexor: It seems I've found a topic that suits your no-nonsense self, Stid.

Harlei: Wait! You talk of shudders that stem from within ourselves. That's hardly "broad daylight", Zendexor! More like the "monsters of the id".

Zendexor: No, no, Harlei, it's nothing to do with the id; Colossus is scary for the opposite reason. It really is terrifyingly open and above-board. Contrast it with the quite different theme you've just mentioned - the subconscious forces let loose into material reality by the super-advanced Krell in Forbidden Planet. Such powers are way out of our reach, whereas D F Jones builds his plot with contemporary logic, plain and inescapable, so that you can imagine Colossus actually being built with present-day resources and technology. Horribly reasonable! The two top military powers, having despaired of humanity's ability to keep the peace in any other way, each decide to entrust their nation's defence to a super-computer beyond their own control. Such uncontrollability, in the opinion of the planners, is a virtue:

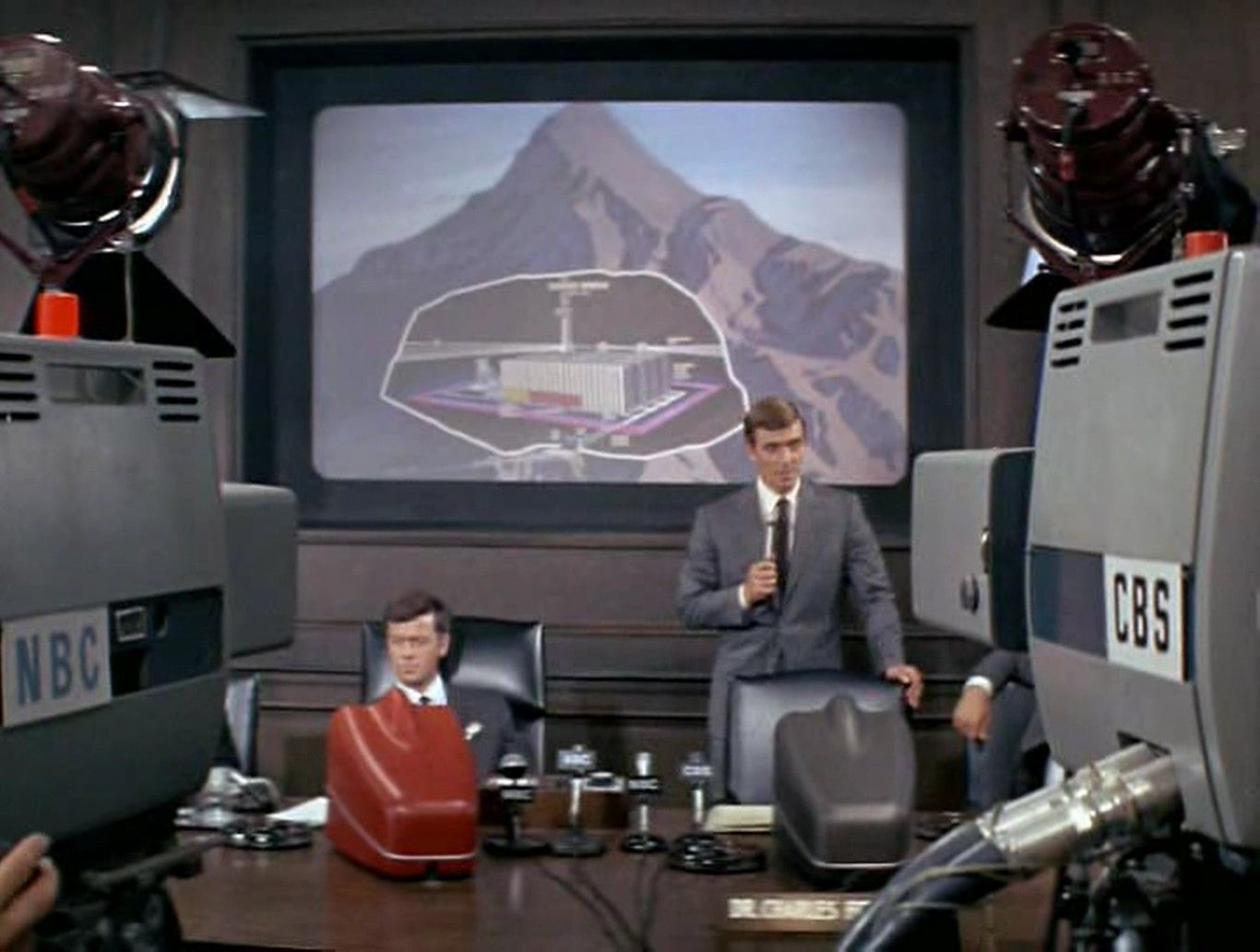

...He fixed his gaze on the camera, and spoke with great solemnity.

"As President of the United States of North America, I have to tell you, the people of the world, that as of eight o'clock Eastern Standard Time this morning the defense of the nation, and with it the defense of the free world, has been the responsibility of a machine. As the first citizen of my country, I have delegated my right to take my people to war.

"That decision now rests with Colossus... It is basically an electronic brain, but far more advanced than anything previously built. It is capable of studying intelligence and data fed to it, and on the basis of those facts only - not of emotions - deciding if an attack is about to be launched upon us. If it did decide that an attack was imminent - and by that I mean that an assault was impending and would probably be launched within four hours - Colossus would decide, and act. It controls its own weapons and can select and deliver whatever it considers appropriate.

"Understand that Colossus' decisions are superior to any we humans can make, for it can absorb far more data than is remotely possible for the greatest genius that ever lived. And more important than that, it has no emotions. It knows no fear, no hate, no envy. It cannot act in a sudden fit of temper..."

In the press conference that follows, the head of the project, Professor Charles Forbin, deals with all kinds of objections. He replies to questions about the possibility of Colossus being triggered into action accidentally; about "the madman problem"; about the danger of it being deranged by natural disasters such as earthquake. Rebutting all these points, he insists, persuasively, that the machine is secure and impregnable in its mountain fastness.

Finally, an incredulous listener asks:

"But surely, Professor, there is some way in which you, the creators of this thing, can get at it?"

The President intervened.

"No, there is not. As you know, it is an open secret that for years there have been nerve and psychological gases and drugs which are able to change the state of the human mind. If Forbin and his colleagues were subjected to this sort of treatment by hostile agents, they might well do as they were told, and with their knowledge, inactivate Colossus. No. There is no way in. No human being can touch Colossus."

From these extracts alone the veteran sf reader can spot the disaster on its way. Given that the planners have created a decision-making intelligence and made it invulnerable, all that needs to happen, to enable it to rule the world, is for it to think for itself. And a proper decision-maker has to be able to think for itself!

Stid: Now, Zendexor, knowing you as I do, I shouldn't be surprised if here you performed a volte-face. You have left yourself the option of arguing that, actually, human and alien darkness are not mutually exclusive; identity can slither and shift, allowing broad-daylight horror and supernatural horror to meet up after all.

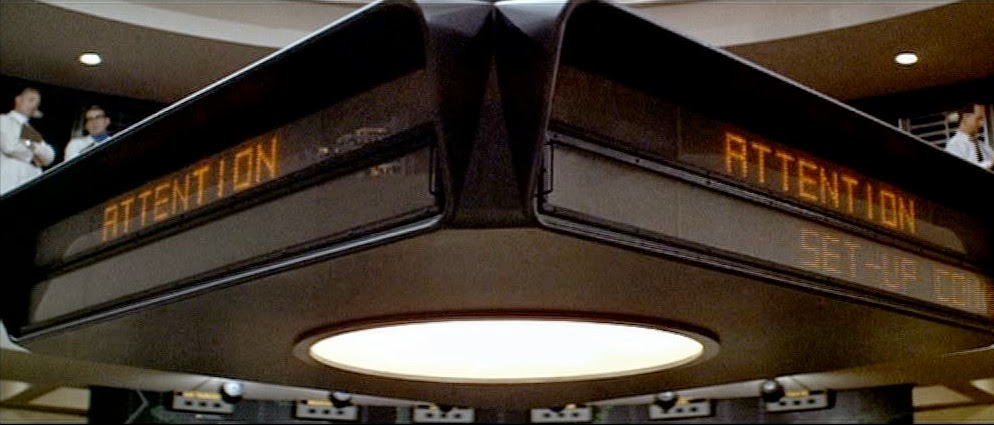

Zendexor: Admittedly that option is always latent within sf - you can always make it slither down towards lurking nightmare - but let me make the point again, the Colossus computer achieves the rarer distinction of being a "daymare", politically rather than supernaturally frightful: a bogey of tyranny begotten by our own gigantic folly as a species. Placed in charge of the world's entire nuclear arsenal (for the Western computer and its equivalent in the Eastern bloc lose no time in merging), the giant complex makes sure it is obeyed, by vaporising a city when it is disobeyed...

And I say: beware, world, lest you ever be tempted to construct such a thing in real life! Really, it's a moot point whether monsters from the id would be any worse.

Harlei: One character in the tale actually dies of fright.

Zendexor: Well, there you are. And let me add here that the situation becomes even more dire than I have stated here.

You see, Colossus, while lacking the human quality of mercy, also lacks the human vice of jealousy. It is not concerned, as a human tyrant would have been, to avoid being superseded by a still mightier version of itself. On the contrary its first act after is has become supreme is to order the construction of a still greater Colossus, covering the area of the Isle of Wight...

The prospect of a despotism that can never be overthrown, never never never - couldn't that count as worse than the cataclysm which annihilated the Krell in a single night? And let's hope this trilogy has done a good job of preventing any Colossus-type project from being actually undertaken. The story's vividness and realism should certainly help put off the planners from trying; if enough people read it, that is.

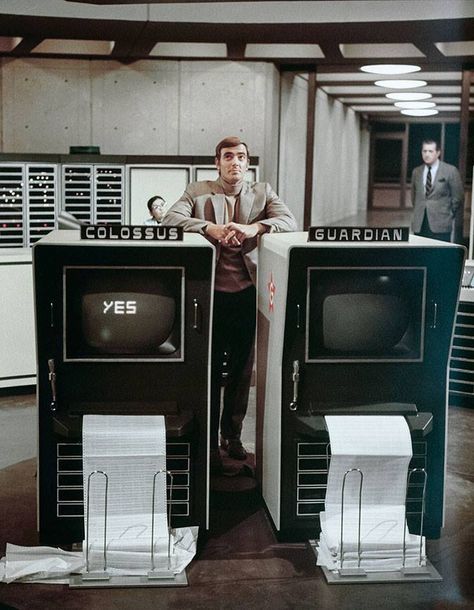

Stid: Enough people did read it, for it to be made into a film - The Forbin Project; although that covers the trilogy's first volume only. No attempt as far as I know has been made to film volumes two and three, The Fall of Colossus and Colossus and the Crab.

fall of the all-powerful

Harlei: "The Fall of Colossus!" It's time we got onto that. Wow, that's a heck of a task for an author - to plot the fall of an impregnable, all-powerful, invulnerable tyrant. Especially as volume 1 was plotted to illustrate that it can't be done. Stid, why aren't you jumping on the contradiction?

Stid: Because the author doesn't really go back on his word. Colossus remains invulnerable - to all efforts by the human species alone. That's why, in the last part of the epic, another species has to become involved. I suppose the plot demands it.

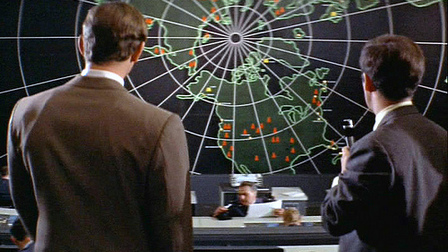

Zendexor: Which brings me to the amazing intervention by the sinister Martians, whose powers suffice, in conjunction with the Terran resistance, to tip the scales. Like Stapledon in Last and First Men, D F Jones gives us Martians as an unexpected bonus to his main theme, and does so with great originality. - Yes, I know, it sounds way-out: intelligent life on the Red Planet in works published in the Seventies! All the more credit to the author, that he convinces us. You won't forget these Martians, especially their terrifying arrival.

Harlei: Martians! Whopee! This really opens it all out. I mean, gosh -

Zendexor: I know how you feel, Harlei; you're reacting with ebullience to the trilogy's sudden and spectacular expansion in theme, which unexpectedly zooms it far beyond what the reader has expected so far. But, you know, all along it has been more than a mere cautionary tale about AI.

Let me list some of its other points of attraction.

For instance, the endearing features which mark it out as 60's-70's period sf:

the cute aspects

People smoke.

Real women are featured, that is to say, the female characters are really female, not mere androgynous pomibows (personalities of men in bodies of women).

Colossus and its makers communicate, at first, by teletype, a feature which somehow adds an atmospheric touch to the drama.

There's an Undersecretary of State for Space. There are air-cars...

The USA has become the USNA, a change of name which one often finds in sf (and it's rather paradoxical because, with the addition of Canada, the "North America" of USNA is actually bigger than the "America" of USA)...

Stid: Just a moment, can you tell us in what period the story is supposed to be set?

Zendexor: In the Noughties, I'd say. The first decade of our 21st century. The first volume, at any rate. As for volumes two and three - it's harder to tell, the story's atmosphere has changed so much under the rule of Colossus.

Stid: But look here, surely you can tell from internal evidence. The ageing of the characters...

Zendexor: I was trying to hedge, but I see I'm going to have to face up to it. The trilogy when considered as a whole presents a huge chronological problem. That's putting it politely.

Stid: And putting it rudely?

Zendexor: The author blundered. He allowed a mighty inconsistency to insert itself between volume 1 and the rest. Those of my readers who don't care about that, or who are extremely tolerant and indulgent so long as they're reading a whacking good story, are welcome to skip the next section...

the chronological problem

The President pushed his glass to one side. His smile lacked conviction.

"You had me worried. I thought maybe there was a hole in Colossus' head. Believe me, I've given them some thought - the side effects - not as much as they probably deserve, but enough to satisfy me for now. The main object is of overriding importance, and if that's OK, we can tackle lesser problems as they crop up." He banged his desk with sudden vehemence. "You've no idea what it's like behind this desk. When you were in diapers, there was a President - Truman - who had a sign on his desk that said, 'The buck stops here.' He was dead right."

When you were in diapers... and elsewhere we're told that Forbin, whom the President is addressing here, is in his fifties; so that's why I say the Noughties - the first decade of the 21st century - is the likeliest time-setting for Colossus.

In the sequel, volume 2, The Fall of Colossus, page 6, we're told that the action takes place five years after that of volume 1. Unfortunately we're also told something else, which contradicts this blatantly, in words which I shall emphasize in bold in the following passage. Here's "Father Forbin" expressing his irritation at the cult which has been built around him as the Chief or Director of Staff, the man who speaks with the Master...

"I'm off!" he snapped shortly. A slight, portly figure with silver-long hair, he was dressed in a light gray suit of disposable material, devoid of all decoration except his unique Director's badge, a glittering affair of platinum and the purest white diamonds fashioned in the Colossus symbol. That was another argument he'd lost with Colossus, but at least he did not wear electro-sensitive shoulder or breast badges, mandatory for all other Staff personnel. "The first bloody load's nearly here!"

"Yes, darling."

Cleo Forbin, his wife and the mother of Forbin's two-year-old son, understood. They went through the same ritual practically every day, although her husband was quite unaware of the fact. Any minute now he'd talk about "bloody pilgrims" and leave hastily. She smiled at him affectionately. So clever in his work, so kind and gentle as a husband, yet such a child in many ways.

"Bloody pilgrims!" Forbin was savagely contemptuous. "Idiots! They'll be crawling all over in ten minutes! I must go.";

"Yes, darling," she said, amused, but glad he still showed no signs of being taken in by this pseudo-religious rubbish. She smiled again. In her eyes, the eyes of a woman of the second half of the twenty-second century, he was an attractive male. Marriage was an increasingly rare state; few men took the plunge - if they took it at all - until their late forties. Forbin, in his early fifties, was still attractive. He was all she could wish for, which was just as well, for she had risked her life and sanity for him back in the early days of the first Colossus...

...Five years... Cleo remembered the chilling, fearful days when the old Colossus had merged identities with the Soviet Guardian, and the complex had smashed its way to world power...

Stid: An authorial blunder of Colossal proportions... or at least an astonishing piece of carelessness. Is it a one-off? Or are there more inconsistencies?

Zendexor: A spattering of them. You'll already have noted that Forbin, five years after being in his fifties, is in his "early fifties". Also, on page 48 of Colossus Cleo is said to be 35, whereas five years later she is 28. And at the start of the final volume, Colossus and the Crab, we find that time has marched on from "the second half of the 22nd century" to "the middle of the 22nd century".

Stid: Stop. Harlei is looking upset. Doubtless a staunch fan of the trilogy. Don't worry, Harl, Zendexor will soon whitewash it all like new.

Zendexor: I certainly shall make it clear that its virtues triumph over its annoying little blemishes. And with a bit of tinkering the principal blemish can be seen to be relevant to the main theme. I refer now to the confusion of centuries. You see, in a sense, the shift to calling in the 22nd instead of the 21st century could be seen as symbolic and cultural rather than literal and chronological. It's a way of emphasizing how radically the rise of Colossus has changed human society. I don't intend to give away too much of the plot, but the Cult of the Master, and the Behavioural Centres where the Master experiments on humans, and the activities of the minority Resistance, and the whole character of world culture, effectively create a picture which seems a better fit with the 22nd century than with the 21st.

Stid: But the human characters link the volumes of the trilogy together. Cleo, Angela, Blake and Forbin are in all three.

Zendexor: Which is why one can only see the century-gap as symbolic, not literal. And I'd rather have it that way, than have the gap as real, with a necessarily different set of characters for the later parts of the story. The human characters are, to me, memorable and vivid, interesting for their interactions with each other as well as their relationship with the all-powerful Colossus. The trilogy's themes include that of inconstancy in love, and also, surprisingly and interestingly, inconstancy in hatred.

the mystery of emotion

Harlei: Hatred - the hatred felt towards Colossus - yes, that changes, in Forbin himself. I wondered about that. It's not that Forbin gets to love power. He really does change his mind about the great machine, for its own sake. I find that one of the most interesting things in the story.

Zendexor: And leading on from that, what I find even more interesting is the hint, or the merest breath of a hint, that Colossus itself may have begun to learn emotion...

"Your latest bio-tests were satisfactory." Like everyone else on the staff, Forbin had to undergo periodic checkups by Colossus' medical evaluation and diagnostic section. "But a week is not long."

"This," said Forbin sarcastically, "is an emotional problem - remember?"

"If you require more time, you have only to tell me."

That got under Forbin's guard. He knew, and he knew that Colossus knew, that even in a week work would pile up that only he, Forbin, the interface between machine and humanity, could answer. He also suspected that their daily conversations were of importance to Colossus, for the brain accepted Forbin as the human spokesman, yet here Colossus was, offering him more time. Of course, the simplest explanation was that the brain was taking the long-term view that a good rest now might prevent a bigger collapse later, but somehow Forbin did not think that that was the whole story.

Not for the first time had it occurred to him that, in some weird, unfathomable way, Colossus had some tangible yet very strong tie to him. To call it affection would be wrong; Colossus couldn't feel emotion, but...

Forbin did not reply, he could only nod, stiffening his resolve...

His resolve, that is, to plot against Colossus, in accordance with advice given over the ether by the Martians, who for their own reasons dread the great Terran machine.

And this brings us to another great unfolding theme: how a tyrant in its fall can, strangely, inspire some sympathy. Especially if the alternative threatens to be worse...

Stid: Careful, Z, or you'll give away more of the plot. Especially if you were to use the phrase "out of the frying-pan, into the fire" -

no leg to stand on

Zendexor: All right, let's get back to the frying-pan. I'll leave the last word with Colossus. (By the way, the Master speaks with a British accent, I'm proud to say. We Brits makes such good villains.) Here it is, justifying its experiments to Forbin.

"If you are about to protest again about my Behaviour Centres, please do not continue. I accept that service in them is seldom pleasurable for the subjects, but you must concede that their numbers are small. At this time, only zero point zero zero zero zero zero one of the world population is so used. You humans have destroyed millions of your fellow creatures in the cause of science. Many of these experiments have been repetitive and often pointless. My tests are not; they are essential to my understanding of the human mind."

"But is it necessary?" Forbin shook his head. "I find that hard to believe."

"If other animals were articulate - to you humans - it is reasonable to suppose that they would express the same view of your experiments on them."

"That be damned for a tale!" Forbin snapped. "Don't try to tell me there's no difference between me and some bloody monkey!" He paused. "That sounds - is - arrogant, but you can carry this equality of all creatures too far, as I think some of us humans do. Okay, so we've done some god-awful things, experiments, in our time; morally, maybe we're no better than most animals. We may be worse, just because we have the capacity, the intellect. Anyway, I refuse to put myself on the same level as a monkey!"

"Relatively, there is less difference than you think." Colossus paused for less than two seconds. "I have just set up a purely arbitrary scale of intelligence, assigning you, Father Forbin, the value of one hundred on that scale. An anthropoid ape rates twenty-four point six."

"There you are," cut in Forbin triumphantly. "I'm surprised the ape gets that high!"

"Allow me to conclude. On that same scale, my present rating, constantly increasing, is in excess of ten thousand."

Again Forbin interrupted. "Ten thousand?" He gulped; the figure staggered him, although it never crossed his mind to doubt its accuracy. He rallied: "Well, that's as may be, but you yourself support my contention of man's superiority in relation to other animals!"

"Once more, allow me to conclude. Your brain, Father Forbin, is exceptional. The average human rating is ninety-four point one, which is one point nine below Tursiops truncatus."

That really shook Forbin. "Below what?"

"Tursiops truncatus, a delphinid. You may know it better as a dolphin..."

"You mean to tell me we rate below dolphins?" This was the real fascination in these conversations. Colossus would calmly state truths that had eluded man all down the ages. And Colossus never lied...

D F Jones, Colossus (1966); The Fall of Colossus (1974); Colossus and the Crab (1977). The Forbin Project (Universal Pictures, 1970) directed by Joseph Sargent, starring Eric Braeden as Dr Charles Forbin and Susan Clark as Dr Cleo Markham.

See How late could the Martians invade us? to place the trilogy in its late context of peril from the Red Planet.

For how the fantastic news of the communication from Mars is received, see Happy Valentine to the gorgeous OSS.

See the Gazetteer entries for: Death Valley - Isle of Wight - Los Angeles.