- Home

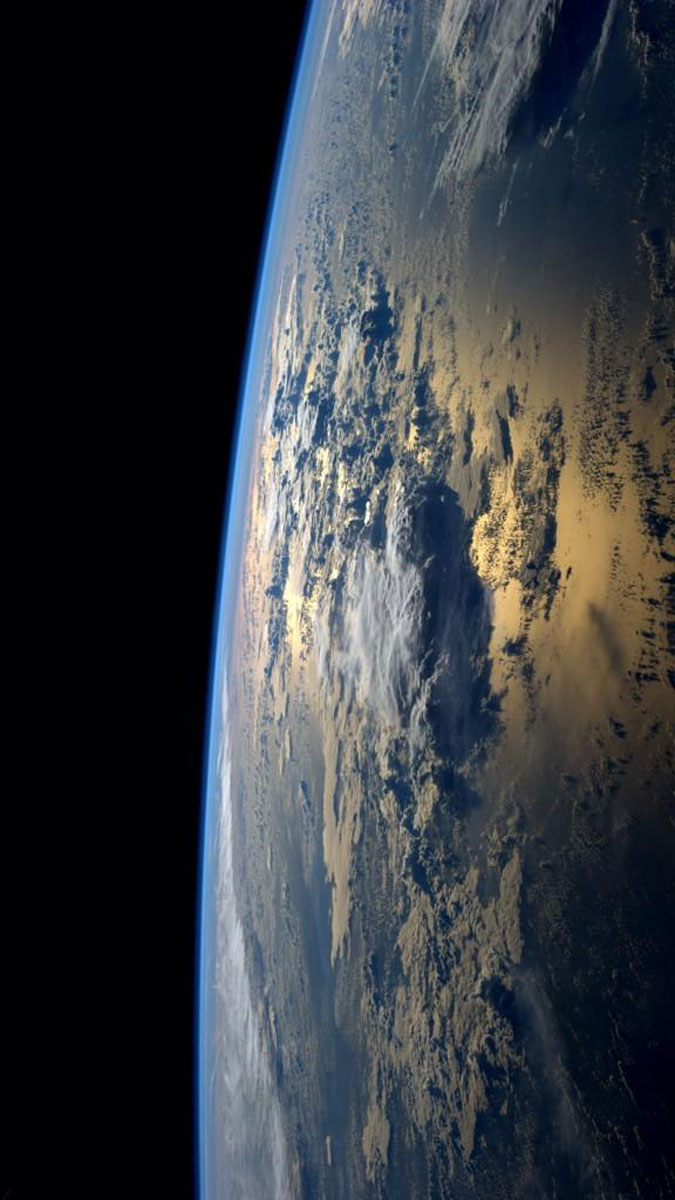

- Earth

the mystery planet called

Earth

[+ links: A Plea for Lost Civilizations - A Relic from the Old Space Program - America's Own Haunting - The Colossus Trilogy - The Drop - Eerie Earths - EU madness - Far Future - H Rider Haggard -

William Hope Hodgson - Robert E Howard - Jasoomian Gathol - Kroth - Man of the World - Morecambe and Heysham - The Old Space Program - Mervyn Peake - Pellucidar - Provided at Generous Prices - The Rise - The Slavanns Must Play - Star's Reach - Tolkien: Tangential Wonder - What to see on Earth - Word-rehab ]

Forgetting all bias, let's consider our world afresh.

Beamed down into wombs, we're born on a mission to Earth, we open our eyes and begin to explore.

It's quite a planet. The greatest rocky body in the System. And loaded with life-forms.

And there's more than meets the eye. We can explore extensions such as Pellucidar and Kroth, plus might-have-beens such as the Old Space Program... not to mention the multiple reality-layers caused by meddlesome time-travellers... and the all alternate Earths, notably in Simak stories, extending the possibilities to infinity...

All this is possible because of Earth's remarkable tendency to throw off enlargements or emanations of itself: a capacity for literary extrusion which I term the Shimmer, and which makes the science-fictional orb a lot larger than that described by geographers - a point which is discussed in our page eerie Earths.

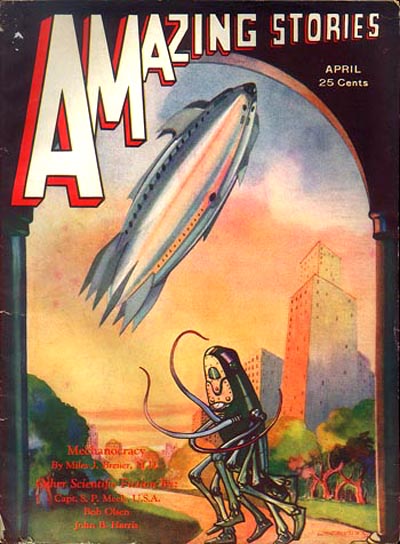

Harlei: Before you go on - I've got an idea: let's start from the Martian point of view! Not just any old Martian, either. One of the high-ups: Mu Tel, cynical yet benevolent Toonolian prince in The Master Mind of Mars, who plays with an interplanetary monitoring gadget, looking sunward towards Earth.

Suppose, being Mu Tel, you catch sight of (for example) Ludlow. What's your reaction?

You exclaim: "Issus! What a culture layer!"

Stid: Why Ludlow? Have you got shares in the place?

Harlei: I did say for example. I actually picked it because I have no connection with it. So like the Unknown Soldier, let it stand for many others. In this case, many another everyday

taken-for-granted view of Earth.

mad Jasoomian jeddak

mad Jasoomian jeddakMore widely, and with whetted appetite, Mu Tel's vision then roves around the entire planet and it really gets him thinking.

"By my first ancestor!! Those Jasoomians have as much land area as we Barsoomians, plus an ocean surface over twice as extensive as the land, and much of it dotted with islands. Though their history is much shorter than ours, their huge, beautiful, exciting world has cities, flying machines, ships, jungles, mountains higher and more numerous than ours, savage beasts, mad rulers, the lot. Only its beautiful princesses seem in short supply, but the potential is there, given the right political reforms..."

even madder Jasoomian jeddak

even madder Jasoomian jeddakStid: Not sure why you're doing this, Zendexor. Why a page about Earth, anyway? What's it doing on this site? Of course one could endlessly list science fiction tales set on Earth - but this website is supposed to be about the Old Solar System. That is, our heritage of dreams about our neighbouring worlds. Dreams dreamed during the first two thirds of the twentieth century, before the age of space probes, but long after the Age of Discovery on Earth.

In other words we're supposed to be focusing on planetary romance which closely pre-dates, and contrasts with, what we learned from the 1960s onwards.

A bright flowering, just before a cut-off.

Jasoomian banth

Jasoomian banthHow, then, is that 1960s cut-off relevant to tales set on planet Earth? There's nothing like that sort of boundary for Earth fiction - no sudden break between Old and New Earth stories. We're living on Earth, we've always lived on it, and since the main terrestrial Age of Discovery occurred centuries before science fiction was invented -

Zendexor: Well, actually, that's arguable. The Travels of Sir John Mandeville...

But no, don't worry, I'm not going to deny, that strictly speaking there's no pre-probe Old Earth contemporary with the pre-probe Old Solar System.

Harlei: Wait, Zendexor, don't give up yet. You could cite lost-race stories by Haggard and Merritt, and the Tarzan tales in which he discovers lost cities and lost empires galore in Africa. And then there's the subterranean and hollow-Earth stuff, Land Under England, The Perilous Descent, Pellucidar...

Zendexor: You're lumping together stuff that is best kept separate. And you're veering away from where I intend to go - but first let me deal with the issues you've raised.

Lost-race tales set on Earth: yeah, there are quite a few of them. And they are a bit sad; I mean they're disappointingly cramped.

Unless, that is, you can "jasoomise" your imagination, as you did at the start of this page (that's to say, view Earth as the mighty Third Planet seen by fresh eyes).

Even if you do jasoomise, though, there's still the fact that a lost-race tale has to be set in a region that's out of touch with the rest of the world - so why not go all the way and set it on another planet? Might as well give the story its very own scope!

(Unless - wait a minute - I need to re-think - unless the very setting of the lost races on Earth marks the positive development of a localised Earth-Shimmer, and thus a welcome enlargement of Earth itself - see the argument in A Plea for Lost Civilizations.)

As for Pellucidar, that, I grant you, is a special case. A theme with dual-genre-citizenship. A terrestrial setting yet combined with the wonder of another world. It deserves a page to itself. As does the far future: another example of Earth-being-'another-world'.

Meanwhile here let's focus on Earth as one of the nine planets.

Stid: Earth is a planet, sure. I knew that, actually.

Zendexor: Try not to be dense. What I'm driving at is this:

Science fiction enables us to visit Earth. All right, our education may have told us that Earth is a planet, but it needs science fiction to make the message sink in. SF shows us we'd never really realized it - never actually grasped the planethood of Earth with our emotions before.

We need this visited Earth. We need sf to rebound it against us freshly. Our vision is then born anew.

Such is what happens to the protagonist of Valeddom, after his return from his Mercurian adventure, when he leafs again through his tatty, stained old children's encyclopaedia where previously his eye had always skidded boredly over the third of the nine paintings on the double-page spread of the nine planets. Now, for the first time, he views the third picture fairly. Now he sees Planet Three as of equal interest alongside the others.

For he has jasoomised (or, if you like, 'valeddomised') his home world at last.

Or one might consider the "Brackettisation" of Earth in Star's Reach: that is to say, its gradual evolution into a kind of analogue of the Brackett Mars, a world of ageing and sinister mystery.

As Eliot says in Little Gidding:

And the end of all our exploring

Will be to arrive where we started

And know the place for the first time.

Stid: I still reckon you're skirting perilously close to the clichés uttered by astronauts...

Zendexor: Relax, I promise not to point out that national frontiers are invisible from space. Or that the biosphere is thin and vulnerable. Or any suchlike screamingly obvious stuff.

Stid: Just as well if you do refrain, because it runs counter to your thesis.

Zendexor: Why do you say that? Surely, "Earth as a planet" is an idea that can be helped either by fiction, or by science and astronautics, or by all of them together.

Stid: Yes, but the chronology of it is against you. You're still trying to fit "Earth as a planet" into the "Old Solar System", whereas in actual fact, the one came just as the other went. The ability to see "Earth as a planet", far from fitting in with the old pre-probe OSS, actually arrived with the space age - that same space age that abolished the OSS.

Get out of that one, Zendexor.

Zendexor: Easy - because you're totally wrong. Earth-as-a-planet long predates the space age. That's what I intend to show you - that Earth wasn't left out when the OSS was developed as a freeway for the imagination. In fact, our world was one of the important stop-offs on the freeway. All OSS worlds reflect upon each other, just as the night side of a crescent Moon can shine by Earthlight. Even the quarantined Earth of the Ransom trilogy - Thulcandra, the Silent Planet - remained part of the picture: we read that the Intelligences of the other worlds remain concerned with Thulcandra, and eventually descend upon it in the great Chapter Fifteen of That Hideous Strength.

I admit, though, that there's bound to be some pressure against Earth-planet as a story setting. We 'know' it too well. Lopsidedly familiar compared with the other planets, it is overpopulated with familiar ideas, familiar themes and humdrum associations which squash its chances for mystery. Like a city under pressure due to limited land area, if it expands it must do so in other directions, like Manhattan bulging skywards. By that I mean, that writers must find a special "angle" to make Earth-as-a-planet interesting.

In which case - let's think about how this is done. What way, or in which directions, do the ideas 'bulge' in Terrestrial science fiction? Or to use the term I suggested earlier, what are the sources of the Shimmer?

Here are six possible answers:

One: An actual frontier, the one which still exists for real, namely the ocean deeps - The Kraken Wakes, The Deep Range, Davy Jones' Ambassador - or the bowels of the earth - Journey to the Centre of the Earth, Land Under England, The Perilous Descent.

Two: Physical extension into a hollow world - Pellucidar - or a newly risen continent (no example springs to mind).

Three: Dimensional extension - Kroth, Sail On! Sail On!, The Autumn Land. I suspect the most extreme example of dimensional out-reach will turn out to be the "prior-universe" foreshadowing in Man of the World. But there's also the terrifying reality-state reachable by "Omega mode" inter-atomic oscillation in Lambda 1 (see the podcast discussion devoted to that story).

Four: Time-extension - The Shadow Out of Time, Last And First Men, Seeds of the Dusk, The Night Land and other tales that reach into the far past and far future.

Five: The might-have-beens of alternate history and in particular the golden age of early astronautics in the Old Space Program - Blast Off At Woomera, The Man Who Sold The Moon, Prelude to Space. Also, deliberately-altered history caused by time-travel and reality-change.

Six: Following on from the previous category: we have the effect of science-fiction itself on reality. Good science-fiction often adds value to a geographical area - imbues it with a kind of cosmic nostalgia, like Simak's Wisconsin - see the page on America's haunting.

Out of these six, perhaps the only one which is not completely self-explanatory is category number three, "Dimensional Extension".

I mean something more than mere parallel or alternate Earths here. (Those are listed as Category Five.) Category Three, Dimensional Extension, is where I'd place any version of Earth with different natural laws.

I therefore use it to include aspects of Earth which share a basic identity with our world but which (as it were) "face out from" it into a different kind of cosmos. For example, the Earth in Sail On! Sail On! is not spherical.

It does have a horizon - only this is "not because we live on a globe, but because the earth is curved only a little ways, like a greatly flattened-out hemisphere", argues one of the voyagers in Columbus's expedition. And it turns out he's right. The ship gets caught in "the topple of Oceanus into space".

Kroth, likewise, is an Earth you can fall off, though Kroth is spherical. It inhabits a universe with unidirectional gravity, which means there's only one direction up, and only one direction down.

Bruce Carter, The Perilous Descent (1952); Edgar Rice Burroughs, the Pellucidar series (At the Earth's Core (1922), Pellucidar (1923),Tanar of Pellucidar (1929), Tarzan at the Earth's Core (1930), Back to the Stone Age (1937), Land of Terror (1944), Savage Pellucidar (1963)); The Master Mind of Mars (1927); Arthur C Clarke, Prelude to Space (1953), The Deep Range (1957); T S Eliot, "Little Gidding" (1942; the last poem in the "Four Quartets"); Philip José Farmer, "Sail On! Sail On!" (Startling Stories, December 1952); Raymond Z Gallun, "Davy Jones' Ambassador" (Astounding Stories, December 1935), "Seeds of the Dusk" (Astounding Science Fiction, June 1938); Robert Gibson, Valeddom - Mercury Awaits (2013); the Kroth trilogy (The Slant (2012), The Drop (2014), The Rise (2015)); Man of the World (2016); John Michael Greer, Star's Reach (2014); Robert A Heinlein, "The Man Who Sold the Moon" (1951); William Hope Hodgson, The Night Land (1912); Colin Kapp, "Lambda 1" (1962); C S Lewis, the Ransom trilogy - also known as the Cosmic trilogy (Out of the Silent Planet (1938), Perelandra (1944), That Hideous Strength (1945)); H P Lovecraft, "The Shadow Out Of Time", Astounding Stories, June 1936; Joseph O'Neill, Land Under England (1935); Clifford D Simak, "The Autumn Land" (The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, October 1971); Olaf Stapledon, Last And First Men (1930); Jules Verne, Journey to the Centre of the Earth (1864, as Voyage au Centre de la Terre); Hugh Walters, Blast Off At Woomera (1957); John Wyndham, The Kraken Wakes (1953).

Note: dates are of publication, sometimes years later than composition, e.g. Clarke's Prelude to Space (published 1953) was written in 1947.

For Earth as the arena for a second Genesis: see characters of worlds.

For a varied discussion of lost races and dimensional stretch, see A Plea for Lost Civilizations.

For the book that taught a fascinated young Zendexor all he knew about

palaeontology and Earth history, see the Diary, 24th November 2016,

regarding Patrick Moore's True Book About the Earth.

For Earth's deepening culture layer, see the Far Future page, the Star's Reach page,

and the OSS Diary for 28th January 2017.

For a non-rotating Earth, see the OSS Diary, 4th February 2017.

See the OSS Diary, 20th March 2017, for the article "Whimsies of Terran history - a mysterious island".

See the Diary entry Planet D'Artagnan for reflections on the parallelism between Dumas and Barsoom.

See the Diary entry A Park-like Future Earth? for Wells' The Time Machine and Simak's Time and Again.

For David I Masson's Mouth of Hell see Tilted Landscape, Pre-Kroth. Sub-genre: "geographical horror".

For cetacean conflict nine million years ago, see A Prehistoric World War.

See Hostile Plants on a Far-Future Earth and the intelligent plants page for Hamilton's early story Ten Million Years Ahead.

For a way to view our Earthly circumstances in a Burroughsian light see I-Spy Jasoom.

For the worn-out Earth of Russell's Dear Devil see A Martian Poet Saves the Human Race.

For the Earth as a living organism, as portrayed in Sir Arthur Conan Doyle's When the World Screamed, see Living Worlds.

For the sub-genre of geophysical romance see the Diary for 23rd and 24th September 2016, and also Pole Shift.

An Electrical Monster refers to David Stringer's High Eight, a horror tale which suggests that technology can trigger new forms of evolution.

For a gradual increase in Earth's mass, see Earth Accretion - Robotic Initiative, referring to Barrington Bayley's The Rod of Light.

For patriotism and the kallomantle see The greatest Terran RPG.

For a delightfully normal prospect see The surprisingly human Vancian future. A sort of "Marsish" Earth is developing in Earth after millennia of galactic spread.