- Home

- >

alien scripts

and the perils of decipherment

in the old solar system

The perils of decipherment? Yes, a dead script is very much alive, full of romantic mystery and possibly sinister menace.

I seemed to be a prisoner, and horror hung broodingly over everything I saw. I felt that the mocking curvilinear hieroglyphs on the walls would blast my soul with their message were I not guarded by a merciful ignorance... - The Shadow Out Of Time

Stid: You've just quoted from what may be Lovecraft's greatest story. And yet, mere "decipherment" is not the "peril", even in that tale. More generally, shouldn't you talk of "pitfalls" rather than "perils"?

Zendexor: Granted, it would seem, by analogy with the epic triumphs of scholarship which we know of in real life - Champollion's with ancient Egyptian, Rawlinson's with cuneiform, Ventris' with Cretan - that in learning to read the script of a vanished culture, you'll encounter enormous challenges, but no actual dangers. At least, not from the glyphs themselves. SF, even OSS SF, doesn't deal in black magic, after all.

Stid: Precisely, which is why I think "perils" seems a bit over-the-top, if we're thinking of serious science fiction that explores the intellectually exciting business of learning to open the window on a vanished alien culture. But then, I suppose that since we're dealing with OSS stuff, realism goes out that window, anyway.

Zendexor: Not necessarily! As a matter of fact, in the first of the three stories we shall consider, the analogy with terrestrial archaeology is in some respects very close. And yet the perils are real, though they're career-threatening, rather than life- or soul-threatening.

Stid: Really? A low-key tale, without blasters going off?

Zendexor: Cerebral and scientific, that's the stuff.

Stid: You sure anyone wants to read it?

finding the key

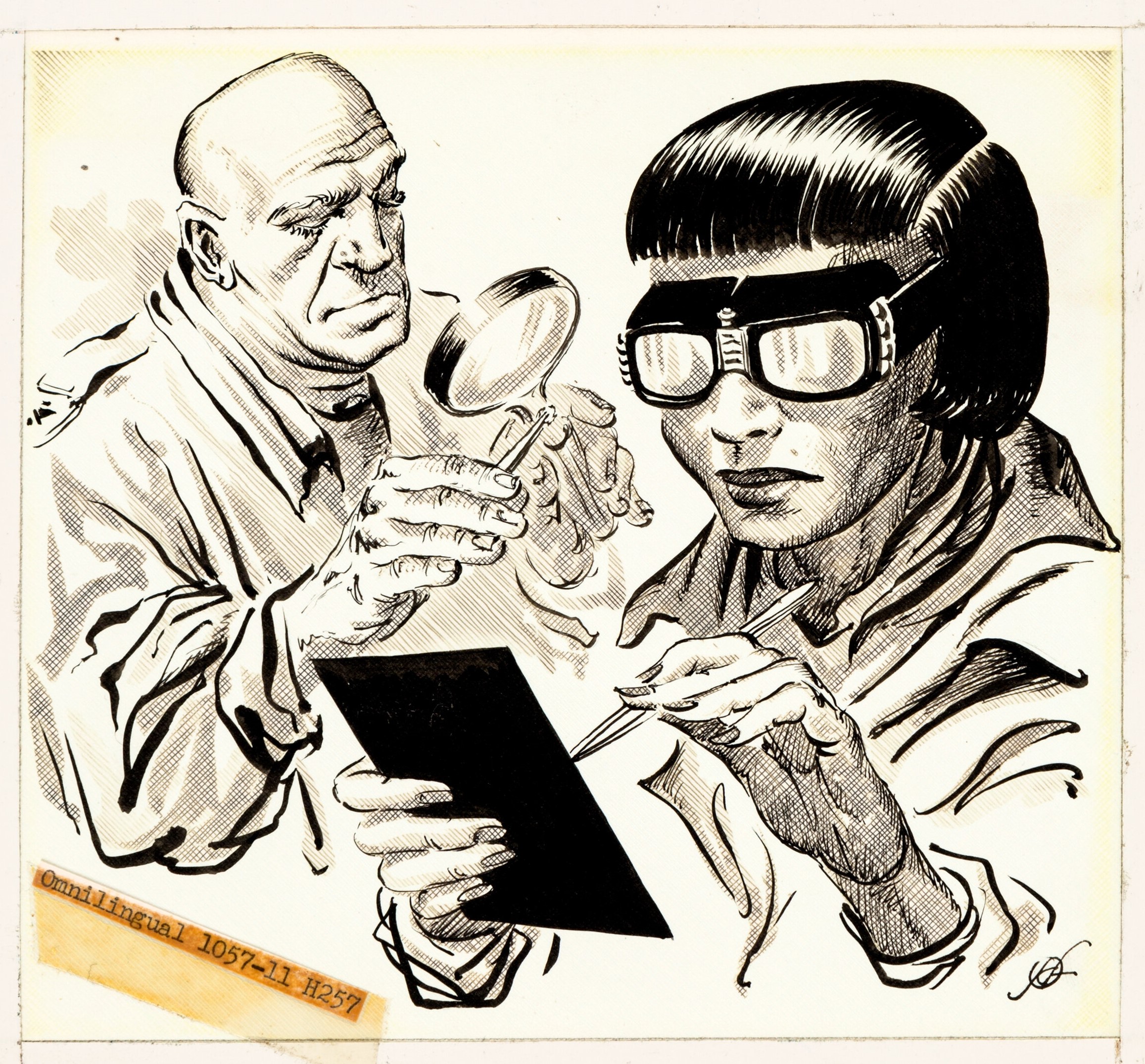

Zendexor: Indeed I can't imagine any reader not being charmed and captivated by Omnilingual. Forty-three pages of delight, set among the first archeological expedition to Mars. Intellect and emotion are both involved. The heroine, Martha Dane, is a likeable idealist who longs to understand the writing of the extinct Martians. But she is the only member of the expedition who insists on believing that decipherment is possible.

She sat down, lighting a fresh cigarette, and reached over to a stack of unexamined material, taking off the top sheet. It was a photostat of what looked like the title page and contents of some sort of a periodical. She remembered it; she had found it herself, two days before, in a closet in the basement of the building she had just finished examining.

She sat for a moment, looking at it. It was readable, in the sense that she had set up a purely arbitrary but consistently pronounceable system of phonetic values for the letters. The long vertical symbols were vowels. There were only ten of them; not too many, allowing separate characters for long and short sounds. There were twenty of the short horizontal letters, which meant that sounds like -ng or -ch or -sh were single letters. The odds were millions to one against her system being anything like the original sound of the language, but she had listed several thousand Martian words, and she could pronounce all of them.

And that was as far as it went. She could pronounce between three and four thousand Martian words, and she couldn't assign a meaning to one of them...

Her friends in the expedition think she is wasting her time; that her quest is hopeless, given that no contact has ever occurred between Terrestrials and Martians, and that therefore there can be no bilingual key, no "Rosetta Stone" to give us an entrée to the Martian language.

Martha's opponent, Tony Lattimer, is a careerist self-promoter who ridicules her efforts. He is alarmed when the leader, Selim von Ohlmhorst, shows signs of believing in Martha after all.

"Are you really beginning to treat this pipe dream of hers as a serious possibility, Selim?" Lattimer demanded. "I know, it would be a wonderful thing, but wonderful things don't happen just because they're wonderful. Only because they're possible, and this one isn't. Let me quote that distinguished Hittitologist, James Friedrich: 'Nothing can be translated out of nothing.' Or that later but not less distinguished Hittitologist, Selim von Ohlmhorst: 'Where are you going to get your bilingual?'"

"Friedrich lived to see the Hittite language deciphered and read," von Ohlmhorst reminded him.

"Yes, when they found Hittite-Assyrian bilinguals." Lattimer measured a spoonful of coffee-powder into his cup and added hot water. "Martha, you ought to know, better than anybody, how little chance you have..."

Lattimer gets really upset when vol Ohlmhorst announces he's staying on Mars permanently.

"We've made a start," vol Ohlmhorst maintained... "I'm going to be able to read some of those books over there, if it takes me the rest of my life here. It probably will, anyhow."

"You mean you've changed you mind about going home on the Cyrano?" Martha asked. "You'll stay on here?"

The old man nodded. "I can't leave this. There's too much to discover. The old dog will have to learn a lot of new tricks, but this is where my work will be, from now on."

Lattimer was shocked. "You're nuts!" he cried. "You mean you're going to throw away everything you've accomplished in Hittitology and start all over again here on Mars? Martha, if you've talked him into this crazy decision, you're a criminal!"

The subsequent personality-clash is very well handled. It ends with an outburst from Lattimer that rather gives the game away. Martha sits, avoiding the eyes of the others as she witnesses the man's seething professional jealousy:

...when you want to be a big shot, you can't bear the possibility of anyone else being a bigger shot...

Meanwhile the story is progressing on many fronts....

Harlei: I was waiting for you to say that, Zendexor. We don't want the bickering atmosphere to take over completely. This is Mars! Discoveries on Mars! If people can't think big on Mars, it's a poor show.

Zendexor: Don't you worry - vistas are continually opening in this story, I can assure you. The Martians, though dead as dodos, are yet, as a challenge to our understanding, amazingly present and real. Much more real, in fact, than they are in many tales that I have read in which they are still living...

They found a globe of Mars, made when the city had been a seaport. They located the city, and learned that its name had been Kukan - or something with a similar vowel-consonant ratio. Immediately, Sid Chamberlain and Gloria Standish began giving their telecasts a Kukan dateline, and Hubert Penrose used the name in his official reports. They also found a Martian calendar; the year had been divided into ten more or less equal months, and one of them had been Doma. Another month was Nor, and that was a part of the name of the scientific journal Martha had found.

Bill Chandler, the zoologist, had been going deeper and deeper into the old sea bottom of Syrtis. Four hundred miles from Kukan, and at fifteen thousand feet lower altitude, he shot a bird. At least, it was a something with wings and what were almost but not quite feathers, though it was more reptilian than avian in general characteristics... About seven-eighths of its body-capacity was lungs; it certainly breathed air containing at least half enough oxygen to support human life, or five times as much as the air around Kukan.

Harlei: The Mars of this story is borderline, a Worn-Out Mars not far from being a Breathable-Air Mars.

Zendexor: Rare pockets of more and more friendly physical conditions play their part in the approach to the climax. So far, no one has found any bodily remains of the Martians themselves; only of their artifacts - their buildings, books, cities.

The high point came when one party, at thirty thousand feet below the level of Kukan, found breathable air...

The high point of mere physical exploration, that is. But then Tony Lattimer brings the archaeological side of things back into the news -

Martha and Selim were working in the museum on the second floor, scrubbing the grime from the glass cases, noting contents, and grease-penciling numbers; Lattimer and a couple of Space Force officers were going through what had been the administrative offices on the other side. It was one of these, a young second lieutenant, who came hurrying in from the mezzanine, almost bursting with excitement.

"Hey, Martha! Dr von Ohlmhorst!" he was shouting. "Where are you? Tony's found the Martians!"

Selim dropped his rag back in the bucket; she laid her clipboard on top of the case beside her.

It seems that Lattimer has now fulfilled his ambition to be a big shot. The public and the media are agog at the news, and have no attention for anything but Lattimer's discovery: a roomful of alien bodies in armchairs around a table: eighteen Martians, "skeletons covered with leather", dead for fifty thousand years.

Stid: Should you be telling us this, Zendexor?

Zendexor: Don't worry, this isn't a spoiler. I don't do that. It would be a spoiler if I were to say too much about what happens next. Martha Dane makes a discovery that trumps Lattimer's and turns the tables on him - she finds her "Rosetta Stone" after all. But as to how she does it, all I can say is, read the story!

I'll give you one clue. If ever humans really do find an alien script to decipher on some other world, where the writers of the script belonged to some advanced though now extinct civilization, there'll be a new factor to consider, an opportunity which did not exist for Champollion, Rawlinson or Ventris who only dealt with pre-scientific cultures...

And now let me summarize. Omnilingual is a wonderfully human tale of science, of fulfilment of the yearning to know. The humanity and the science and exploration all fit together perfectly.

Harlei: Good enough for me! I'd love to have been on that expedition!

Stid: Good boy! Shows you aren't limited to blood-and-thunder.

Zendexor: We're all singing from the same hymn sheet here. And now, having agreed on our appreciation for the gentler forms of discovery, let's move on to a rather more fraught encounter with an alien script.

being found by the key

Those squiggly scribbles running in rows along the buildings, which I assumed to be mere decorative graffiti when I first came to Ixli, and which I now knew to be inscriptions in Noleddern, were sticking little needles of meaning into my mind as I walked past, whispering tales from the buildings' history, so that, as my unwary glance travelled along the lines of scribble, my sight began to film over with mental movies, ghost images of the structures being erected amid the bustle of a long-vanished age. I wrenched my gaze away; I wasn't ready for all this just yet. - Valeddom

Transplanted Earthmind Hugh Dent, in his Mercurian body, doesn't need to strive to read the Mercurian "ultimate language". Rather, it costs an effort not to read it.

Stid: Is this where we arrive at black magic at last?

Zendexor: No, we're still in science fiction, for this is a science-fictional idea:

"You experienced the sharper headache because you are a precocious reader of Noleddern." Once more I caught that flicker of gloating.

"All right," I sighed. No point in pretending that I don't know.

Noleddern is the ultimate language. It is picture-writing - hieroglyphics - taken to a point so advanced that it somehow cuts out the whole intermediate business of symbols; the sight of it doesn't merely signify, it merges with, it is, the meaning. So the language can be read without being learned.

Harlei: I like the sound of that: a new language which the reader of it doesn't need to learn! But for the story's sake, the reader must hope it isn't too easy.

Stid: No chance of that. Hints abound, that there'll be a price to pay.

Zendexor: And the adaptation process is not trite. Though you don't "learn" Noleddern, you do have to grow into it. As the narrator says:

It only works when you've reached a certain stage of development. Before then, it's just scribble, but when you're ready, ignorance is suddenly no longer possible - the scribble writhes into significance, you see it, you get the full message, instantaneously.

Yet though it's straightaway inside you, you don't necessarily digest it quite so fast. That's the scary part of it. You may not know at first exactly what it is that your mind has swallowed, but at the same time you do know that there's no getting rid of it and that you inescapably will know.

Harlei: So here the "decipherment" is more like swallowing - as in, "oops, I've swallowed something; wonder what it'll do to my insides". I agree with the narrator: this could be scary.

Zendexor: Scarily irrevocable. And that's also true generally, regarding how one grows into being able to read the stuff.

You'll discover the unfortunate fact that education doesn't prepare you. Guides to Noleddern merely tempt you, making you look forward to reaching reading age. Then suddenly it's worked its way inside you and it's too late to pull back.

It seems that the only defence is to be too stupid to grasp it or too weak to endure it. Otherwise, you're in for it. And once you get so far as to sit at a table in the Great Library at Ixli, with a volume of Mercurian history open before you, well, you're really in for it... your mind is going to travel, and meet what is described on the page. See the discussion of Mercurian evil, on our Valeddom page.

And come to think of it, see the Mercury page itself. In particular the discussion of Mercury in myth as connected with language - a link brilliantly evoked by C S Lewis in That Hideous Strength. The use of the language theme in Valeddom is surely influenced by this tradition: it's surely not coincidence that there the ultimate language is something Mercurian.

luckily losing the key

Now that we've travelled to Mars and Mercury in our discussion of alien scripts, let's try yet another planet for our third story. We're going to explore that fantastic planet named Earth.

Stid: Just a moment. Remember, we want alien scripts. Mere Atlantean or Muvian or Lemurian stuff won't do. It needs to be non-human.

Harlei: Let Zendexor approach the theme in his own way! I bet he can provide some non-human intelligences that are as native of Earth as we are. Can't you, Z.?

Zendexor: In a sense... You'll guess in what sense, when I say, we're going back to the tale I mentioned at the beginning of this page: The Shadow Out Of Time.

Stid: Ah, time. The enormous stretches of it, that form Planet Earth's history. So vast, you could fit anything in, I suppose, during those millions upon millions of years. Technological civilizations... they'd have to be advanced, to create writing materials which survive the megayears for us to find their books and read them. And as for decipherment... well, we might learn to read them in the end. For at least they would be natives of the same planet as we. Moreover some scientific concepts would be in common between us.

Zendexor: You're on track, in a sense...

Stid: What's this "in a sense" supposed to mean? You got something up your sleeve, or what?

Zendexor: The plot of The Shadow Out Of Time is a complete contrast to that of Omnilingual. And yet it is, in a sense, a tale of archaeological discovery. Deep underground in what is now Western Australia lie the archives of the Great Race, cone-shaped beings who flourished in the Triassic Period.

The archives were in a colossal subterranean structure near the city's center... Meant to last as long as the race, and to withstand the fiercest of earth's convulsions, this titan repository surpassed all other buildings in the massive, mountainlike firmness of its construction.

The records, written or printed on great sheets of a curiously tenacious cellulose fabric, were bound into books that opened from the top, and were kept in individual cases of a strange, extremely light rustless metal of grayish hue, decorated with mathematical designs and bearing the title in the Great Race's curvilinear hieroglyphs...

But I'm telling this all very misleadingly. Selecting passages carefully so as not to give the amazing plot away.

Stid: What can you say, then?

Zendexor: I say, read it, and be knocked flat by the spellbinding brilliance of a great tale. And though it would be a crime to give away the ending, I'll add this:

The narrator, Professor Peaslee, finds a book, dating from the time of the Great Race, that he can read. And the reason he can read it, turns out to be the ultimate in terrifying irony.

Robert Gibson, Valeddom (2013); H P Lovecraft, "The Shadow Out of Time" (Astounding Stories, June 1936); H Beam Piper, "Omnilingual" (Astounding Science Fiction, February 1957)

For the related theme of Solar System language, see the OSS Diary for 20th July 2016.

See also reply re Mercury myth influencing Valeddom.

For the "documentary" approach that is so enjoyable in Omnilingual, see also Academia on Mars, concerning The Dead Sea Bottom Scrolls by Howard Waldrop.