- Home

- Mars and its moons

Mars

[+ links to: A Coercive of Mars - A Distant Sun - A Return to Bradbury's Mars - A Rose for Ecclesiastes - Academia on Mars - Allen M Steele's Enigmatic Mars - Arabella of Mars - Barsoom - Barsoom and NSS Mars Matchup - Be Seeing You - Leigh Brackett - Ray Bradbury - But is it NOSS? - The Cold White North of Mars - The Colossus Trilogy - The Crimson Courts and My Martian Dreams - The Date of the Invasion - Field Observations from a Far-Future Mars and beyond - Global Dispatches and Extraordinary Gentlemen - Home on Mars - The Implicizer Aimed at the Diagram of Power - The Implicizer Aimed at the Moth-Men of Phobos - In the Courts of the Crimson Kings - In the Tombs of the Martian Kings - The Inorganic Character of RSS Mars - Long Live the Billion-Year Spacereich! - The Magistrate - Man to Mars and Moon - Mars et la terre à la belle époque - Mars Quiz - The Martian Crown Jewels - Martian Landings in The War of the Worlds - No Man Friday - Old Mars - Out of the Silent Planet Overview - Pirates on Mars Again - Red Planet - Sailing the Seven Spaceways - The Sands of Mars - Shoals - Thoughts on Michael Moorcock's "The Lost Canal" - Time To Rest - Wanderers of Mars - What makes a good Mars story - What to see on Deimos - What to see on Mars - What to see on Phobos - World of Never-Men ]

MARS!! The most storied planet of them all! A banquet of scenes, shapes, sizes: adventures, alien creatures, civilizations... and the Red Planet's personality overarching them all.

Stid: Tell me, Zendexor, how the dickens are you going to impose some structure on all this mass of material?

Zendexor: Well, let's try and sort it.

natures

I see (broadly) three versions of Mars. Three sub-genres of Mars science fiction. And of these we only need consider the first two.

First sub-genre: the Breathable Mars (BREM).

This, though it has its harsh side, is a world you can go about on without breathing equipment or pressure suits.

It's the Mars of Edgar Rice Burroughs, Leigh Brackett and Ray Bradbury, but also of other, shall we say, more realistic tales - I mean realistic in mood, despite the oxygenated air.

Traditional BREM stories range from

the wonderful romps of the Barsoom series to the more speculative A Martian Odyssey, the mysterious and dramatic Vault of the Beast and Vulthoom (both of which hinge upon the reactions of ancient Martians to an even more alien being from somewhere else), the staid fascination of Omnilingual

(barely a BREM - the Martian air is breathable at one single

low-altitude location mentioned in the story), the stylistic marvel of A Rose for Ecclesiastes and the haunting

reflection of Time to Rest. And finally we have the neo-OSS In the Courts of the Crimson Kings - which combines modern planetology with BREM ideas.

The War of the Worlds is a BREM story in a way, although the action takes place on Earth not Mars - for since the invading Martians can breathe our air, it follows that we could breathe theirs.

Second sub-genre: the Worn-Out Mars (WOM).

This is closer to reality than the BREM, insofar as on the WOM you need breathing equipment at least, probably with a pressure suit as well.

Life exists, but usually not at an advanced level, though Red Planet and No Man Friday are exceptions to this with their wonderfully conceived intelligent Martians. Also, the remarkable Duel on Syrtis powerfully depicts a threadbare Martian ecology which nevertheless has the collective power to resist a big-game-hunting Earthman.

More typically the WOM is the 1950s Mars of Arthur C Clarke and Patrick Moore, an inspiring arena for Man's struggle to colonise a harsh and almost-but-not-completely dead world.

In my view the archetypal WOM masterpiece is The Sands of Mars.

The focus is full on the standard model Mars colony, with domes,

tractor-vehicles, etc, and it all lives and is fresh and real and

personal, and so it succeeds in being exciting for its own sake.

Harlei: I wonder in which category you'd place Old Faithful - BREM or WOM? On the one hand, Mars is certainly worn out - in Martian society the old are only kept alive when they are particularly useful. Old Faithful (or "Number 774" as he is known to his own people) has opened communication with Earth - but that isn't deemed sufficiently "useful".

...He had lived the allotted span fixed by the Rulers.

With food and water as scarce as they were, no one had the right to live longer unless he had proved through the usefulness of his achievements that it was for the good of all that he be granted an extension. Otherwise the young and strong must always replace the old and weak.

...but nevertheless the Martians live and breathe, restricted though their lives are.

Zendexor: Call it a BREM, then.

Harlei: But on the other hand because it's a story about the first voyage between Mars and Earth, told mostly from the Martian point of view, how can we tell whether the Martian atmosphere (breathable of course by Martians) is breathable by us?

Zendexor: Oh all right, Old Faithful doesn't really fit my plan, I admit. Just as well you mentioned it, though - this page would be woefully incomplete if I were to ignore such a classic tale. Let's place it on the border between the two sub-genres, BREM and WOM.

As for the third sub-genre - it comprises the realistic, probably lifeless Mars which we know from space probes.

We shall not be exploring this. Read Kim Stanley Robinson's trilogy if you want the hard real dead stuff. It's a magnificent work, but not relevant here. His Mars does eventually become breathable, but only as a result of humans' efforts at planetary engineering; and what may be done in the future to today's Mars is just as obviously outside the scope of an Old Solar System website as is today's Mars itself.

makers

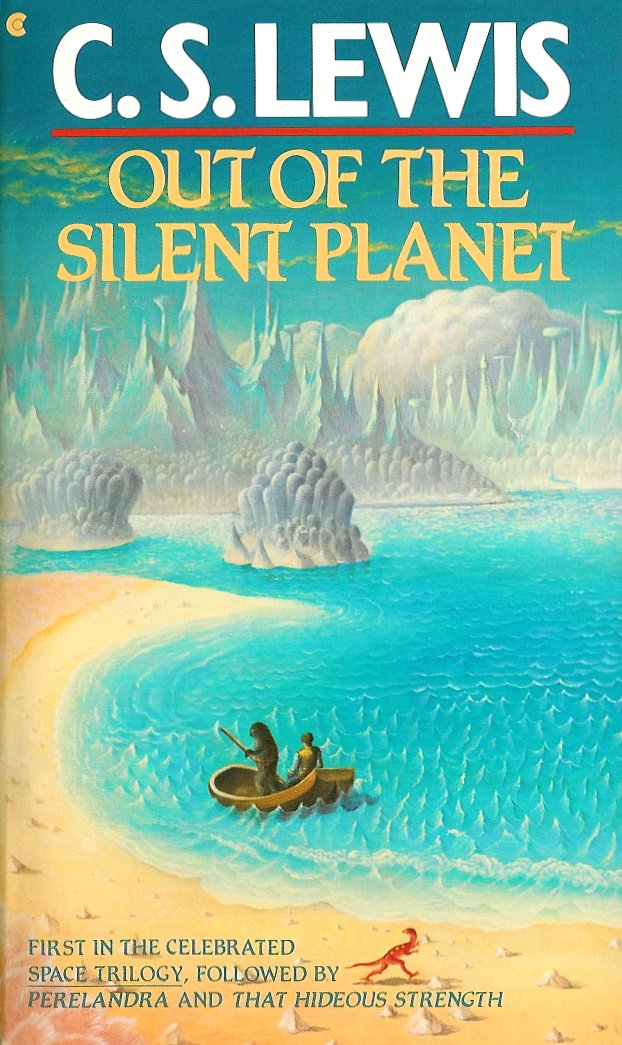

Harlei: Hmm... yes the BREM/WOM distinction sounds useful, but, er, how would you classify Out of the Silent Planet? Is its Mars a BREM or a WOM?

Zendexor: A tactful question! It's your polite way of hinting to me that my pigeon-holing won't work - at least not for that novel, which is one of the best Mars tales ever, perhaps the absolute best. Well, no matter - just call Out of the Silent Planet a BREM-WOM, for truly it is both. That's to say: Malacandra (Lewis' Mars) is a BREM down in the canyons and a WOM up on the lifeless tableland.

(Also, there are some broad low-lying areas which remain breathable, though the hero is merely told about these; he doesn't get to see them.)

Stid: Your BREM and WOM are of some use to sort the heap of tales, but do they reduce it enough? Still a bit too vast to be covered with one web page each, if that's what you're planning! So maybe it's time to try out another set of pigeonholes -

Zendexor: Go ahead, Stid, show us your taxonomy.

Stid: My suggestion is, that we sort by author-type, instead of by setting.

Here are four types of Old Solar System author:

First type: "realistic-back-then". Those

who cared about getting it right. They wrote stuff based on the best knowledge available at the time.

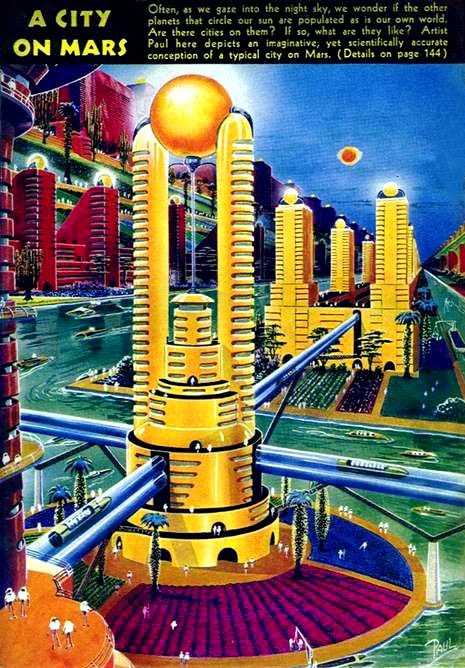

A City on Mars by Frank R Paul

A City on Mars by Frank R PaulThis "knowledge available at the time" group cuts across the other categories - because the available knowledge changes with time. I'd say, on a hunch, that although A Martian Odyssey is BREM and The Sands of Mars and No Man Friday are WOM, yet Stanley Weinbaum and Arthur C Clarke and Rex Gordon are all realistic-back-then - though I can't prove it.

Harlei: Why not? Don't you know enough?

Stid: That's right, I don't - yet.

To prove that scientific opinion

about Mars really did undergo such a change between the early 1930s and

the early 1950s, that a BREM was just as realistic for Weinbaum as a WOM

was for Clarke and Gordon - well, I'd need to know a lot more than I do about the

history of planetary science. Give me time. Meanwhile -

Zendexor: Stid, the way you talk about these realistic authors, about how they aim scrupulously at "getting it right" - aren't you begging the question -

Stid: Yeah, yeah, I get the point you're going to make - that "getting it right" according to myth and tradition is just as valid as "getting it right" according to science.

But realism happens to be my yardstick here, all right? So, now let me get on with my sorting of writers. I've described the "realistic back then" type. Next comes the "borderline-realistic-back-then".

This second author type writes stuff that is old-fashioned, but still acceptable - dubiously acceptable - to the science of that time.

It's hard to differentiate between this group and the third one, but I think - I'm not sure - that I'd place Edgar Rice Burroughs here - at any rate, the ERB of 1911, at the start of the Barsoom series.

Third author type: "borderline-unrealistic-back-then".

These are the writers who took advantage of the

popular ignorance, to squeeze an out-of-date Mars into acceptance for

the sake of the story. Brackett could fit here, I think. C S Lewis also belongs in this group. He admitted it himself: he already knew the "canals" of Mars

were no longer seriously believed in by scientists at the time he wrote Out of the Silent Planet.

Harlei: Thank goodness he didn't let that stop him.

Stid: I've almost finished: let me get on to the fourth and final type on my list.

This last author type I call the "new-unrealistic". Defiant retro-writers, these. They are the ones who don't give a damn if they flout current scientific knowledge.

Lin Carter belongs here, his four Martian adventures deliberately anachronistic. Note, though, that even for these "retros" it's not true that anything goes. For example you couldn't get away with ignoring the true size of Mars, or the location of its orbit. And of course we have the more recent S M Stirling - whose In the Courts of the Crimson Kings is far more ambitious than anything by Lin Carter.

Zendexor: You need to find out more about the history of science, Stid, specifically the history of Mars-science, before you can be sure of your "Author stance" categories. It all depends on what was known -

Martian Canal by Chesley Bonestell

Martian Canal by Chesley BonestellStid: True, but I can speculate. I'd be prepared to bet that, in their heart of hearts, planetary scientists weren't sure about dismissing the Martian "canals" until the Mariner 4 probe reached Mars in 1965; in fact I'd go further and say that even then, since that probe was only a fly-by and imaged only a small percentage of the surface, hopes of the "canals" persisted until the first Mars orbiter, Mariner 9, in 1971-2.

A popular-science article, "Intelligent Life in Space" by Ben Bova, as late as 1963, expressed quasi-belief in the "canals" - the author thought they had been photographed, but he wasn't sure whether they were artificial. That's one indicator. We could find others, maybe chart them on a timeline...

Zendexor: In that case, Lewis can't have been certain that there weren't really some canals or "handramits" on Mars.

Stid: Ah, but he thought it very unlikely.

nurtures

Harlei: Listen, you two. All this may be quite interesting but if you're not careful, you'll involve yourself in a stack of work. Suppose you do manage to plot your timeline, Stid, what happens next? I can just see you setting up a grid, with BREM and WOM on one axis and your four Author-stances on the other. That would give you no less than eight possibilities.

Stid: Is that too much?

Harlei: It may be enough to spoil the fun. I want to suggest another way. Let me take over for a bit. Or rather - let Mars take over.

Zendexor: A Martian invasion.

Harlei: If you want to put it that way. I'm suggesting we try to group our material, not according to physical setting (as Zendexor suggested) or author attitude (as Stid suggested), but according to types of Martian culture.

Stid: Great idea. Only problem is - you'll never do it. The field is far too diverse. Unless you're prepared to give individual treatment to every author who's ever invented a Martian culture. And that approach won't bring any kind of order - it's not classification at all. You'd just be frolicking about in infinity.

Harlei: Ah, but watch my structured frolic:

I can arrange all tales about Martians along a comprehensibility spectrum. Ranging from the straightforward to the utterly mysterious.

Zendexor: But are there any straightforward Martians? Aren't they all exotic and mysterious? Won't any author worth his salt make efforts to tinge his Martians with mystery?

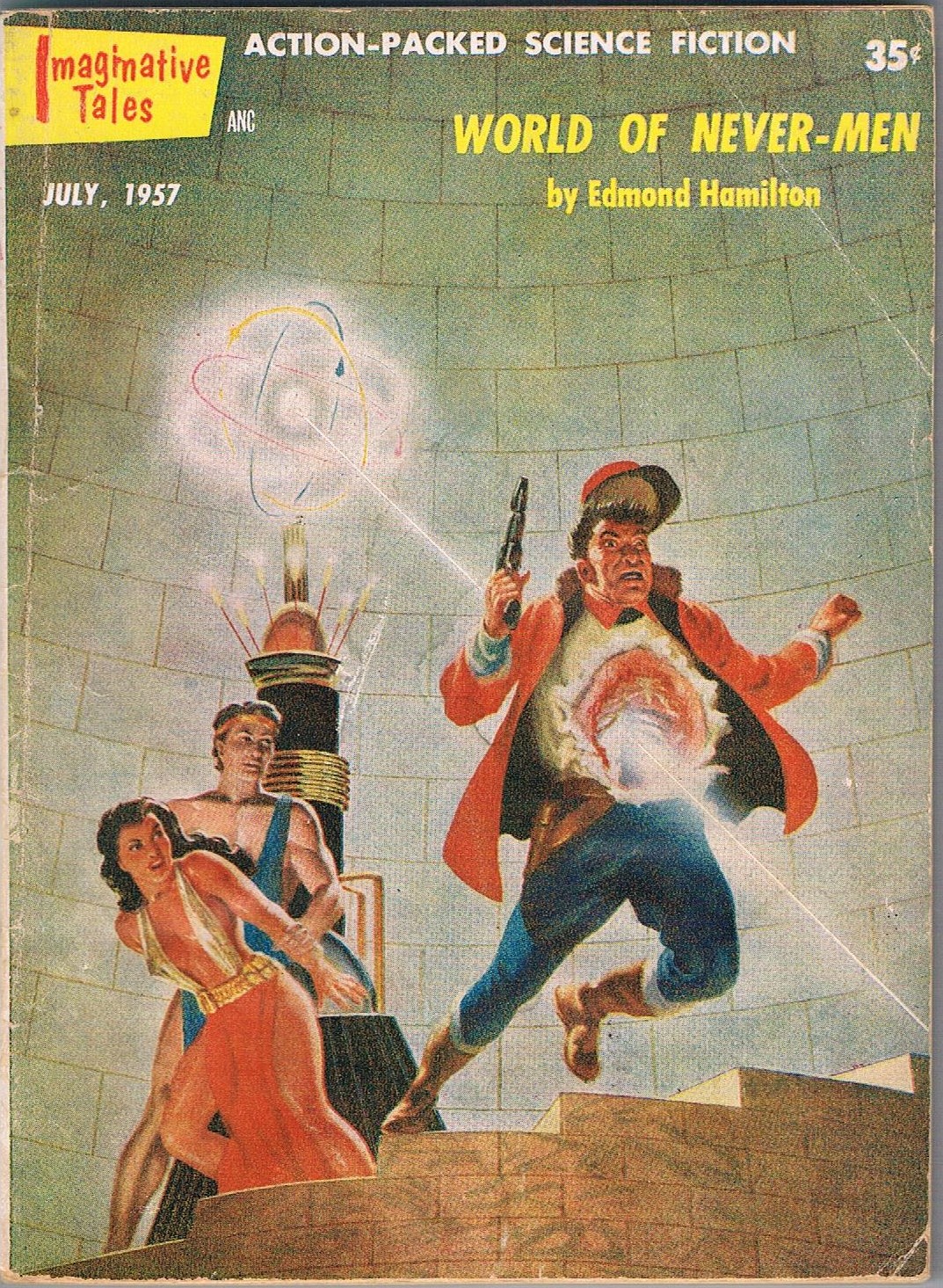

Harlei: "Tinge" is right. The straightforward Martians have just enough aura of mystery to give the story sufficient colour. A Martian, just by being a Martian, is cloaked in exotic glamour. Authors of the "straightforward" kind are concerned to paint a certain type of easy picture, with archetypes which the reader can greet like old friends. Many great tales are like that. The Secret of Sinharat and World of Never-Men are fine examples. The strangeness is a tincture. Excellently administered; but a tincture, no more. But then there's another kind of author, another kind of tale. At the other end of the spectrum, the heavy mystery end.

Stid: Where reside the "incomprehensible" Martians, I take it.

Harlei: Let's say, they're the stories where the cultural mystery is not just a part of the "costume" or colour of the tale, but of its inner nature. These stories... or some of the glimpses we get in these stories... are not contributions to the "standard model" Mars, so much as additions to it, extensions to it. Tales like Huddling Place, The Crystal Egg, Vulthoom... They are never swashbuckling yarns, though they may be adventurous enough. And then you have the cloud-like Martians who invade Earth in Last and First Men. They really are the goods. They deserve a volume of lit. crit. just for themselves. Stapledon gives us the origin and evolution, the physiology, the psychology, the culture, science, art and religion of his utterly original Martians, intelligent clouds of microscopic sub-vital units:

...Just as a cell, in the terrestrial form of life, has often the power of altering its shape (whence the whole mechanism of muscular activity), so in the Martian form the free-floating ultra-microscopic unit might be specialized for generating around itself a magnetic field, and so either repelling or attracting its neighbours. Thus a system of materially disconnected units had a certain cohesion. Its consistency was something between a smoke-cloud and a very tenuous jelly. It had a definite though ever-changing contour and resistant surface. By massed mutual repulsions of its constituent units it could exercise pressure on surrounding objects; and in its most concentrated form the Martian cloud-jelly could bring to bear immense forces which could also be controlled for very delicate manipulation. Magnetic forces were also responsible for the mollusc-like motion of the cloud as a whole over the ground, and again for the transport of lifeless material and living units from region to region within the cloud...

After a chapter on "The Martian Mind" we come to "Delusions of the Martians":

...After the age of racial massacres they sought to persuade themselves that the excellence, or ethical worth, of any organism depended upon the degree of complexity and unity of its radiation. Century by century they strengthened their faith in this vulgar doctrine, and developed also a system of quite irrational delusions and obsessions based upon an obsessive and passionate lust in radiation.

It would take too long to tell of all these subsidiary fantasies, and of the ingenious ways in which they were reconciled with the main body of sane knowledge. But one at least may be mentioned, because of the part it played in the struggle with man. The Martians knew, of course, that "solid matter" was solid by virtue of the interlocking of the minute electro-magnetic systems called atoms. Now rigidity had for them somewhat the same significance and prestige that air, breath, spirit had for early man. It was in the quasi-solid form that Martians were physically most potent; and the maintenance of this form was exhausting and difficult. These facts combined in the Martian consciousness with the knowledge that rigidity was after all the outcome of interlocked electro-magnetic systems. Rigidity was thus endowed with a peculiar sanctity. The superstition was gradually consolidated, by a series of psychological accidents, into a fanatical admiration of all very rigid materials, but especially of hard crystals, and above all of diamonds...

...all known diamonds were exposed to sunlight on the pinnacles of sacred buildings; and the thought that on the neighbour planet might be diamonds which were not properly treated, was one motive of the invasion.

So there you are. Hardly standard-model Mars, as you'll doubtless admit. Typical of the inexhaustible richness of that masterpiece, Last And First Men, that it tosses off an unequalled Martian culture as well as giving us two billion years of future Earth.

Zendexor: I absolutely agree; but since Stapledon is in a class of his own - since, in fact, each individual piece of writing at that fissiparous mystery-end of the spectrum has to be in a class of its own - I prefer to go back a step and look at something else you said. Just now you slipped that phrase "standard model Mars" quietly into the debate for the second time. If there is such a thing, we ought to look at it full in the face.

Stid: Yeah, nail the cliché - then we'll get somewhere.

Zendexor: Knowing you, Stid, I expect that what you mean by "get somewhere" is: give each story a certain number of points according to how far it can avoid "cliché".

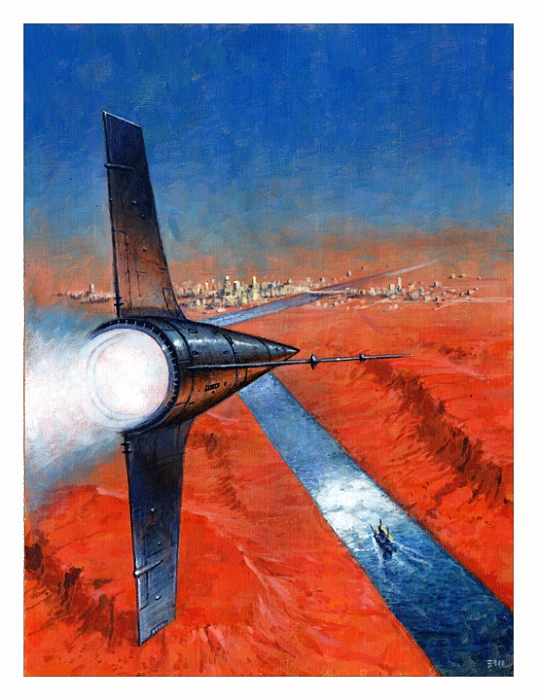

Stid: Right. The cliché Mars - the dying, drying-up world full of deserts, crumbling ruined cities, and wise enigmatic sword-wielding Martians, occasionally stumbling over fragments of the lost scientific wizardry of their ancient forebears - all this is all right as an undercoat to a genre, but doesn't do for the gloss finish. The reader wants something more.

It's like the Wild West. The archetypal Wild West of literature and films. It's not enough - a good story has got to go beyond it...

For example there are the stories which suggest that evolution on Mars might be forced - by the harshness of conditions there - to push ahead into categories of life unknown on Earth. The mysterious biospheric co-operation of Duel on Syrtis comes to mind. Or the awesome realization that comes to the narrator in No Man Friday:

...what I had not thought of was that there might be some other creature which had developed since Mars was filled with life like Earth. That such a creature should come into being during the slow decline of the planet's life was perhaps inevitable, but I had not thought of it any more than I had solved the problem of how life had come into being at all on a planet that now possessed no sort of sea and which lacked what life most needed, oxygen and water.

Such a creature would have to be independent of supplies of oxygen from the air. It would have to be able to sustain its body heat regardless of heat or cold or night. It would have to derive its total energy from lower forms of life. It, on Mars, would have to prey on the animal kingdom, and be dependent on it, even as animals on Earth lived only because of the plants that drew energy from the sunlight and the bacteria that drew nitrogen from the air and made it available in the soil. On Earth, man drew oxygen from the air and drank water as a mineral, but for all the rest he was completely dependent on the complex substances built up by other living things. Only one stage further would evolution have to go, and then...

So that's why I think Harlei's spectrum from "straightforward" to "mysterious" could be re-named - to put it bluntly - as the range from "hackneyed" to "interesting".

Zendexor: The reason you put it that way, Stid, is that you want to demand that every Mars story be assessed entirely on its own merits, rather than by how well it conforms to some standard model of OSS literary Mars - the "cliché" as you call it, or the set of recurring elements which make up a body of myth greater than its parts, as I call it.

Stid: Assess a story according to its merits - what in Space can be wrong with that?

Zendexor: Ah, but it can be argued that conformity with genre-myths is one of the merits of a story!!!

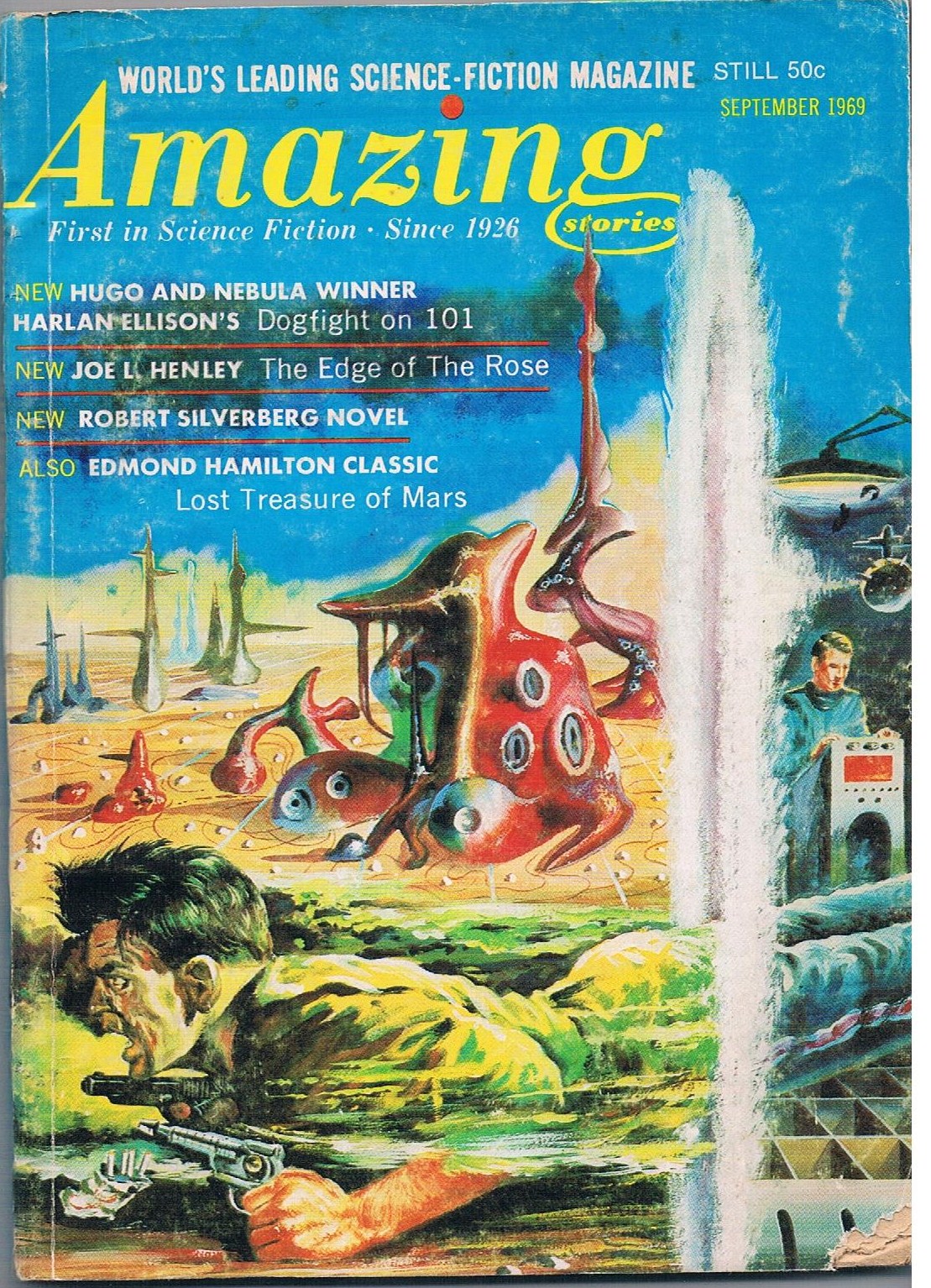

Of course, if you don't hold this view, fair enough. You will then have to class a tale such as The Lost Treasure of Mars or World of Never-Men as second-rate, because really there is little or no point to those stories apart from the excellent way in which they epitomise the motifs of standard model Mars.

And you know, Stid, I'm sometimes in a mood to agree with you - almost! After all, you only have to compare a standard-model tale with Out of the Silent Planet to see there's really no contest.

One problem with the standard-model approach, as exemplified with the Leigh Brackett version of Mars, is what I call COMOLD - the common-origin let-down. The boring idea that the people of Mars are distantly related to us.

Fortunately she also describes some real Martians - the scaly people in The Last Days of Shandakor, and the evil giants in People of the Talisman. But the folk in The Secret of Sinharat (one of her best stories) are unfortunately related to us, and so are most of the ancients in The Sword of Rhiannon (though we can hope that the Quiru aren't, and the ophidian baddies of Caer Dhu certainly aren't).

Stid: By the way, how come all these Celtic names on Mars...?

Zendexor: Probably part of the common-origin scourge.

COMOLD is a drag, no doubt about it. To get away from it, to find indubitably real Martians, you need to turn to the mysteries of Red Planet, No Man Friday, Out of the Silent Planet, Vulthoom... or even Barsoom. At least ERB's human Martians are real home-grown convergently-evolved denizens, born in the Valley Dor at the south pole of Mars twenty-three million years ago. Sorry, must shut up. Anti-COMOLD is a hobby-horse of mine.

Stid: Anyhow, it brings us to a conclusion: that for story-strength, the mysterious end of the spectrum wins out over the straightforward end.

Zendexor: Except that the best tales are both mysterious and straightforward. They make the mystery so real, it becomes part of our life.

So-called alien-ness then becomes just another beautiful colour in our existence. I mean to say, what else can one make of The Martian Chronicles?

Yes, it's time we got onto this one. I've been putting it off, because it's such a challenge to any sf critic.

Stid: It's a mood-piece, that's all.

Zendexor: Yes - but book-length! It could never have been done as a novel, but because it's constructed of interlinked stories and fragments of narrative and description, it builds the mood like a pointillist builds a painting.

The sf themes are all familiar, recurrent, clichés if you like; yet Bradbury's style - "blunt-ethereal", I call it - nets those clichés into a unified dream and then tacks it on to our lives. Mars thus becomes part of our mental furniture, whether we are sf readers or not. Almost, you might say, a mainstream-dream. Hardly genre sf at all - it's the mainstream that has been enlarged.

Phew! Let's hurry back into our genre ghetto and end this page with the archetype of archetypes of Mars, the immortal scene-setting paragraphs of Vulthoom:

It was the Martian hour of worship, when the Aihais gather in their roofless temples to implore the return of the passing sun. Like the throbbing of feverish metal pulses, a sound of ceaseless and innumerable gongs punctured the thin air. The incredibly crooked streets were almost empty; and only a few barges, with immense rhomboidal sails of mauve and scarlet, crawled to and fro on the sombre green waters.

The light waned with visible swiftness behind the top-heavy towers and pagoda-angled pyramids of Ignar-Luth. The chill of the coming night began to pervade the shadows of the huge solar gnomons that lined the canal at frequent intervals. The querulous clangours of the gongs died suddenly in Ignar-Vath, and left a weirdly whispering silence. The buildings of the immemorial city bulked enormous upon a sky of blackish emerald that was already thronged with icy stars.

A medley of untraceable exotic odours was wafted through the twilight. The perfume was redolent of alien mystery, and it thrilled and troubled the Earthmen, who became silent as they approached the bridge, feeling the oppression of eerie strangeness that gathered from all sides in the thickening gloom. More deeply than in daylight, they apprehended the muffled breathings and hidden, tortuous movements of a life forever inscrutable to the children of other planets. The void between Earth and Mars had been traversed; but who could cross the evolutionary gulf between Earthman and Martian?

The people were friendly enough in their taciturn way: they had tolerated the intrusion of terrestrials, had permitted commerce between the worlds. Their languages had been mastered, their history studied, by terrene savants. But it seemed that there could be no real interchange of ideas. Their civilizations had grown old in diverse complexity before the founding of Lemuria; its sciences, arts, religions, were hoary with inconceivable age; and even the simplest customs were the fruit of alien forces and conditions.

At that moment, faced with the precariousness of their situation, Haines and Chanler felt an actual terror of the unknown world that surrounded them with its measureless antiquity...

Poul Anderson, "Duel on Syrtis" (Planet Stories, 1951); Leigh Brackett, The Secret of Sinharat (1949, 1964); "The Last Days of Shandakor" (Startling Stories, April 1952); The Sword of Rhiannon (1953 - first appeared as "Sea-Kings of Mars" (Thrilling Wonder Stories, June 1949)); People of the Talisman (1964 - an expansion of "Black Amazon of Mars" (Planet Stories, March 1951)); Ray Bradbury, The Martian Chronicles (1950) - also published as The Silver Locusts; Edgar Rice Burroughs, the Barsoom series (A Princess of Mars (1912, 1917), The Gods of Mars (1913,1918), The Warlord of Mars (1913-14, 1919), Thuvia, Maid of Mars (1916, 1920), The Chessmen of Mars (1922), The Master Mind of Mars (1928), A Fighting Man of Mars (1931), Swords of Mars (1936), Synthetic Men of Mars (1940), Llana of Gathol (1941, 1948)); Lin Carter, the "Mysteries of Mars" series comprising: The Man Who Loved Mars (1973); The Valley Where Time Stood Still (1974); The City Outside the World (1977); Down to a Sunless Sea (1984); Arthur C Clarke, The Sands of Mars (1951); Raymond Z Gallun, "Old Faithful" (Astounding Stories, December 1934); Rex Gordon, No Man Friday (1956); Edmond Hamilton, "Lost Treasure of Mars" (Amazing Stories, 1940); "World of Never-Men" (Imaginative Tales, July 1957); Robert A Heinlein, Red Planet (1949); C S Lewis, Out of the Silent Planet (1938); H Beam Piper, "Omnilingual" (Astounding Science Fiction, 1957); Clifford D Simak, "Huddling Place" (Astounding Science Fiction, 1944; collected into City (1952); Clark Ashton Smith, "Vulthoom" (Weird Tales, September 1935); Olaf Stapledon, Last And First Men (1930); S M Stirling, In the Courts of the Crimson Kings (2008); A E Van Vogt, "Vault of the Beast" (Astounding Science Fiction, August 1940); Stanley Weinbaum, "A Martian Odyssey" (Wonder Stories, July 1934); H G Wells, "The Crystal Egg" (1897); The War of the Worlds (1898); John Wyndham, "Time to Rest" in The Seeds of Time (1959); Roger Zelazny, "A Rose for Ecclesiastes" (The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, November 1963)

For an extension of the BREM / WOM range, see the OSS Diary for 3rd October 2016, in which I argue for a third category, FNOM, split off from WOM. The discussion continues in the following day's diary entry, regarding possible objections to WOM.

For a perfect and exquisite tale about a sophisticated native Mars, including a Martian detective, see The Martian Crown Jewels.

For ancient Mars, see the page on primordial worlds.

For the Martian "long season", see the OSS Diary for 27th August 2016, and also

Mars' obliquity.

For the uppity Martian vegetables in Seedling of Mars and Seeds of the Dusk, see the page on intelligent plants.

For an interesting slant on Martian ethics - their "no excuses" mentality - see the page on moral dimensions.

The "characters of worlds" page has a section on glowing globular Martians.

For a discussion of The War of the Worlds and related matters, see: the OSS Diary, 29 June to 6 July 2016; also the OSS Diary, 22nd August 2016, concerning the plausibility of the "sarments"; Martian Landings in The War of the Worlds; and Global Dispatches and Extraordinary Gentlemen; also The Date of the Invasion.

For man and landscape on C S Lewis' Mars, see Out of the Silent Planet - Overview, by Antolin.

See the OSS Diary, 15th October 2016, for points in favour of the early Mars (1908-9) of Gustave Le Rouge.

For the size of Mars, see the OSS Diary for 18th October 2016.

The contrasting locations in history of the Golden Age of Mars in Burroughs and Brackett is discussed in the Diary for 3rd November 2016.

For the negative view of Mars in Philip K Dick's The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch, see the Diary for 10th November 2016.

See the Diary for 28th November 2016 for our sad lowering of expectations concerning life on Mars. For John W Campbell's chirpier comments on the possibility of life on Mars see the Diary for 25th November 2016. For thought-provokingly plausible imagery of possible Martian life see Candidate for Martian Moss. For Arthur C Clarke's surprising optimism see Dating the Demise.

For Patrick Moore's Mars, see the OSS Diary for 22nd November 2016.

For Mars as a refuge after an increase in solar radiation makes Earth uninhabitable, see the OSS Diary for 4th December 2016.

For the cosmically lonely ancient Martians of ten million years ago, see the OSS Diary for 11th December 2016.

See Beetles or winged folk - Who rules Mars? for a misreading of The Crystal Egg.

For a discussion of Martian moods - cheerful, fatalistic - see the OSS Diary for 15th December 2016. Includes comment about John Wyndham's Sleepers of Mars.

For Edmond Hamilton's humorous take on the clichés of standard model OSS Mars fiction, see the OSS Diary for 16th December 2016.

For actually managing to get bored with Mars, see Another lot who don't know how lucky they are.

For Eric Frank Russell's Martians, see the OSS Diary for 4th January 2017.

See the OSS Diary for 7th January 2017 for Percival Lowell's certainty about intelligent life on Mars, and an extract from his Mars as the Abode of Life. For a notable year in the Mars canal furore see Hearts Leaped in 1905.

For what is possibly the most recent invasion from Mars, see the OSS Diary for 11th January 2017, and for 14th February 2017, in which I allude to the Colossus Trilogy.

For an attempted pre-emptive power-grab by Mars against Earth, see the OSS Diary for 13th January 2017, regarding Loophole by Arthur C Clarke.

For The Crucible of Power by Jack Williamson see the Diary for 26th January 2017,

"Williamson's Wide-Screen Epic Novella".

See the OSS Diary, 2nd February 2017 for comparative Martian zoology in Burroughs and Moorcock.

For a neo-OSS take on the Red Planet see Allan M Steele's enigmatic Mars.

For the Mars Expedition Number One diary-report given in Gordon A Giles' Via Asteroid, see the OSS Diary for 13th February 2017.

For a late-realistic take on Martian life see the OSS Diary, 11th March 2017, regarding Clarke's Transit of Earth.

See the OSS Diary, 12th March 2017 for System-wide oppression by monstrous Martian brains. For more Red Planet evil see Origins of Martian Ruthlessness.

For David D Lavine's The Wreck of the Mars Adventure see Sailing the Seven Spaceways.

See Reconsidering a Unique Martian Tale for a Mars civilization invisible to most people but not all, in Shoals by Mary Rosemblum.

For more on the Standard Model Mars, see the OSS Diary for 4th April 2017, including a Mars episode from Edmond Hamilton's The Ship from Infinity.

For which fictional Mars one might prefer to live on, see the OSS Diary for 12th April 2017: "Wishful Thinking Mars - But Which One?"

The classification of Mars tales is further discussed in the Diary for 3rd and 4th October 2016.

For Chad Oliver's The Reporter see Conversation in a Martian Bar.

For Martian archaeology see: Alien Scripts - Wide-Eyed Forward Gaze at 2012 - Academia on Mars.

For terraforming see Sacrifices for a future Mars.

For Terrans "going native", see The New Martians.

For a Mars story that does not feel like Mars, see Dylan Jeninga's report, Out of... Mars?

For Howard Waldrop's "documentary" style tale The Dead Sea Bottom Scrolls, see the report by Dylan Jeninga, Academia on Mars, mentioned above in the note on Martian archaeology.

For a 1959 invasion story on TV see Mars and the Twilight Zone.

For a benevolent visitor from the Red Planet see A Martian Poet Saves the Human Race.

For the history of opinion see 1956 - The Last Hope for Old Mars?

See A Martian Trait - Brain-Swapping Surgery for an overlapping theme linking Burroughs' The Master Mind of Mars with Edmond Hamilton's Doom Over Venus.

One step up from Bradbury's Martian resistance discusses Wallace West's Dawningsburgh.

Robert F Young's The First Mars Mission, which encompasses both OSS and RSS versions of the Red Planet, is discussed in Ambivalent Mars.

Rocklynne's Far-Future Mars offers some comment on What makes a good Mars story.

Mature Martians offers some thoughts on three overlapping works from different authors who portray Martians as having renounced space travel and/or a high-tech existence.

A space-boot in both camps discusses straddling the OSS / RSS boundary with particular reference to Mars stories by Arthur C Clarke, John Varley and Lin Carter.

The idea that photosynthesis on Mars leads to a different result than it does on Earth is mentioned in Blue Martian Vegetation.

For the doom-laden astronomy of the Red Planet's superstitious civilization, as described in Frederick Pohl's The Martian Star-Gazers, see Delta Cephei and 1572.

For some AI illustrations see Midjourney Mars.

For interstellar explorers from the Red Planet see Star-roving Martians.

For linking fiction with factual locations see the Gazetteer entries on Martian places, and also the Diary entries, Extending the Gazetteer to cover Mars and Linking Lowell's Mars to the standard map.

Test your otherworldly wisdom with Mars Quiz - Tale To Author and Mars Quiz - Author To Tale.