europa

[ + reference/page links to: Europa Dive - The Colorless Colossus of the Cold -

What to See on Europa ]

Among Jupiter's moons, Europa is the smallest of the Big Four but still a respectable size, only slightly smaller than Earth's Moon. A major focus of interest for modern planetary science, Europa also has its place in the Old Solar System.

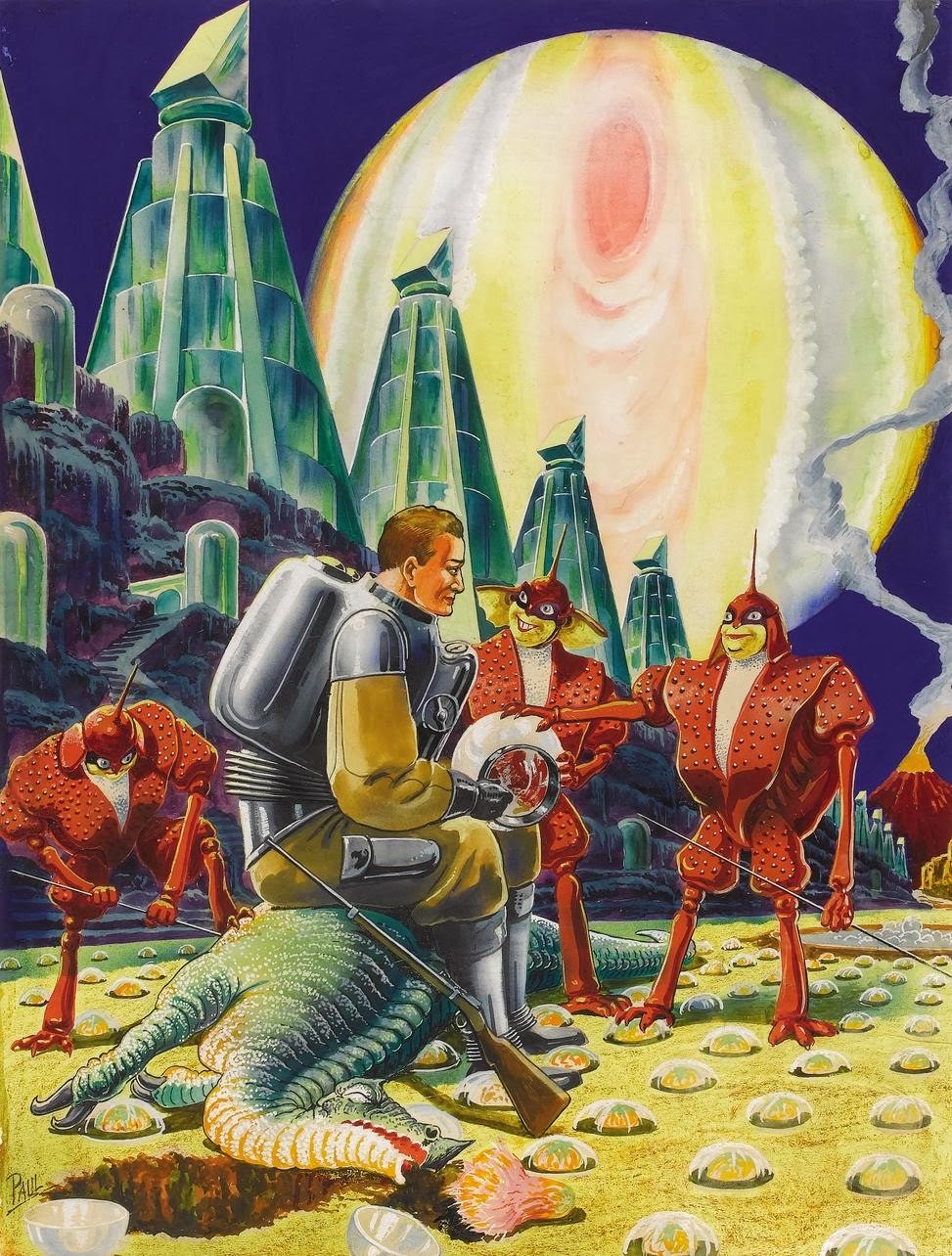

Harlei: The Frank R Paul painting "Life on Europa" suggests a native civilization, advanced enough to build those conical towers...

Zendexor: As usual Paul gives us a fascinating (and rather winsome) spur to the imagination... making us ponder, with a wistful nostalgic smile, on what might have been. But unfortunately I can't link Paul's painting to the stories I want to discuss.

Stid: But presumably you are going to try linking those stories with each other. So then, Zendexor, let's hear your attempt to bring order out of chaos, and to eke out some literary scraps into something rich. You're going to try to convince me that there's a Europan theme, a Europan character, an identifiable culture or personality of Europan settings, in sf.

Zendexor: It's not that hard to find. I contend that the key concept is that of marginal, or borderline, habitability. Writers in pre-space-probe days did know as well as we do that Europa is smaller than the other main moons of Jupiter. Therefore, that was the particular moon they were most likely to chose out of the four, if they wanted to write about a harsh, biologically-borderline environment.

oases of marginal life

So in the 1936 story Redemption Cairn:

In some ways Europa is the queerest little sphere in the Solar System, and for many years it was believed to be quite uninhabitable. It is, too, as far as seventy per cent of its surface goes, but the remaining area is a wild and weird region.

This is the mountainous hollow in the face towards Jupiter, for Europa, like the Moon, keeps one face always toward its primary. Here in this vast depression, all of the tiny world's scanty atmosphere is collected, gathered like little lakes and puddles into the valleys between mountain ranges that often pierce through the low-lying air into the emptiness of space.

Often enough a single valley forms a microcosm sundered by nothingness from the rest of the planet, generating its own little rainstorms under pygmy cloud banks, inhabited by its indigenous life, untouched by, and unaware of, all else...

...queer forms that crawl now and then right up out of the air pools, to lie on the vacuum-bathed peaks exactly as strange fishes flopped their way out of the Earthly seas to bask on the sands at the close of the Devonian age.

Stid: A good quote, and yet I could find quotes that show environmental harshness in imagined settings on the other Galilean moons. For example The Lotus Engine which you yourself discuss on the Io page. That's a world that dried out completely, into a desert. Can't get harsher than that.

Zendexor: Two answers to your point. First, I'm suggesting a mere preponderance, not an absolute supremacy, of the harsh-environment idea for Europa. Second, The Lotus Engine does give us a past civilization on Io, which is richness of a kind - nothing comparable is available for Europa, as far as I know.

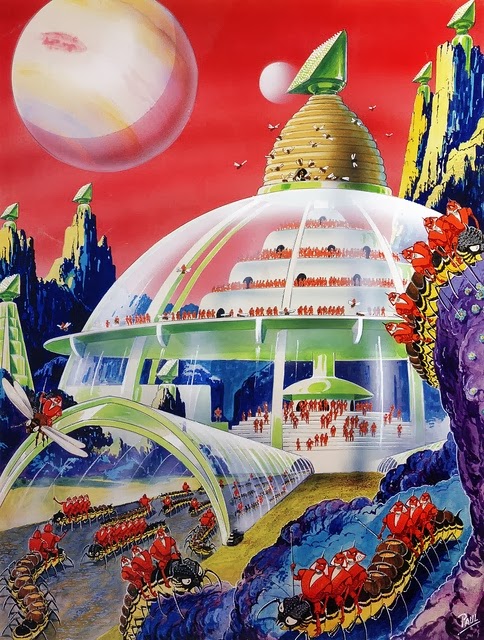

Stid: The Frank R Paul paintings you're decorating this page with are pretty comparable, I'd say, with any richness of alien civilization anywhere!

Zendexor: You're right, they're gorgeously, irresistibly colourful as usual with Paul - but they are only pictures, not stories. A pity they aren't accompanied by their own stories!

Stid: Well anyway, they do show a civilization. Europan architecture, no less.

Zendexor: Paul the draughtsman could never resist inventing alien buildings. But now let me bring in the definitive Europa story...

Stid: Definitive? That's a large claim.

a trek into destiny

Zendexor: Repetition is a masterpiece of science fiction. In its 33 pages it manages to give us both a tale of non-stop thrills, of excitement and suspense, and a thoughtful reflection upon human destiny. It is a tale of survival against odds; at the same time it is a psychological study, of how an experienced politician wins over the young hot-head who has been assigned to kill him, converting the would-be assassin to a statesmanlike cause. And the action takes place amid the setting of the most memorable version of Europa: a fantastically rugged little moon whose core is "jockeyed around by the Sun and Jupiter". (Whereas in Redemption Cairn Europa is warmed directly by heat from Jupiter, in Repetition it's the gravitational/tidal effect which gives the satellite some marginal habitability.)

...Thomas examined their surroundings. He felt his first real chill of doubt as his eyes and mind took in that wild and desolate hell of rock that stretched to every horizon. No, not every! Barely visible in the remote distance of the direction they would have to go was a dark mist of black cliff. It seemed to swim there against the haze of semi-blackness that was the sky beyond the horizon. In the near distance the piling rock showed fantastic shapes, as if frozen in a state of writhing anguish. And there was no beauty in it, no sweep of grandeur, simply endless, desperate miles of black, tortured deadness - and silence!

He grew aware of the silence with a start that pierced his body like a physical shock. The silence seemed suddenly alive. It pressed unrelentingly down upon that flat stretch of rock where they stood. A malevolent silence that kept on and on, without echoes, without even a wind now to whistle and moan over the billion caves and gouged trenches that honeycombed the bleak, dark, treacherous land around them. A silence that seemed the very spirit of this harsh and deadly little world...

The younger man, Bartlett, who has been sent to kill Thomas, regards his job as having been accomplished - Bartlett has sabotaged their transport, marooning them both in the wilds of Europa, and has then told Thomas:

An Accidental Memory - Moody Blue - https://www.deviantart.com/moodyblue/art/An-Accidental-Memory-779452870

An Accidental Memory - Moody Blue - https://www.deviantart.com/moodyblue/art/An-Accidental-Memory-779452870"...We're at least twelve days from civilization - that's figuring sixty miles a day, which is hardly possible. Tonight, the temperature will fall to a hundred below freezing, at least, though it varies down to as low as a hundred and seventy-five below, depending on the shifting of Europa's core, which is very hot, you know, and very close to the surface at times. That's why human beings - and other life - can exist on this moon at all...

"Well, if the cold doesn't kill us, we're bound to run into at least one bloodsucker gryb every few days. They can smell human blood at an astounding distance; and blood for some chemical reason drives them mad with desire. Once they corner a human being it's all up. They tear down the largest trees, or dig into caves through solid rock. The only protection is an atomic gun, and ours went up with our suits. We've got only my hunting knife. Besides all that, our only possible food is the giant grass-eater, which runs like a deer at the first sight of anything living, and which, besides, could kill a dozen unarmed men if it were cornered. You'd be surprised how hungry it is possible to get within a short time. Something in the air - and, of course, we're breathing filtered Europan air - speeds up normal digestion. We'll be starving to death in a couple of hours."

"It seems to give you a sort of mournful satisfaction," Thomas said dryly.

The young man flashed: "I'm here to see that you don't get back alive to the settlement, that's all."

As the gripping plot unfolds, the statesman, Thomas, turns out to possess survival skills that Bartlett the colonist lacks, which increases the tension between the two men, so that Bartlett becomes more dangerous as his respect for Thomas unwillingly increases.

And the drama is compounded by the setting - an unforgettable little world with its grass-eaters and bloodsucker grybs, its loneliness and silence.

A classic if ever there was one; haunting in its juxtaposition of wide political issues with a hazardous trek of two individuals through perilous terrain. The older man muses:

"I have talked about repetition being a rule of life. But somewhere along the pathway of the Universe there must be a first time for everything, a first peaceful solution along sound sociological lines of the antagonisms of great sovereign powers..."

That solution depends upon the survival of one key figure at a pivotal moment in history. And so the trek across Europa - the question of whether Thomas can stay alive - acquires political significance for the future of humanity.

There's an echo of this theme - of personal survival linked to human advance - in the other story, Redemption Cairn, though in that tale what's at stake is a technical formula rather than an inter-planet political deal. But both plots hinge on the ability of one man to solve an apparently insoluble problem, of how to get from A to B and stay alive.

The nature of that challenge invites the reader to sense that there's a special hugeness about small worlds; it's the theme of Valeddom again: the dark infinitude of outer space soaking in, as it were, to the small world's bones. And of the four Galilean moons, we sense it the most in Europan tales.

shavings off the topic

Harlei: We can also rough it with the convicts in Mutiny on Europa...

Stid: Zendexor likes to save his whammies for last, so as to end the page on an impressive note. He's not going to like you trying to slip Mutiny on Europa onto the page when we've just discussed the vastly greater Repetition.

Zendexor: Don't worry, Stid, let Harlei present his fragment. It's not bad, and it's by an author who always casts his spell in any OSS tale. Go on, Harlei, add another shaving or clipping to the gradually rising heap of Europa fragments. The more we get, the solider the gestalt...

Harlei: Here goes then. After all, B movies and B stories let us have fun.

...While I loosened the rock with my drill, my companion picked it up. Around us scores of other convicts also were drilling, hammering, chipping. Guards in black, armed with atomic beam-pistols, watched us vigilantly as we worked.

In the dull green sky the sun, a very small and feeble sun, was sinking westward. Over the eastern horizon bulked a colossal, cloudy white globe. It was Jupiter, the monster, molten planet of which this world, Europa, was a satellite. This was the farthest outpost of pioneering Earthmen, this wild, jungle-covered moon on which they had planted this little prison colony to which were sentenced the most desperate criminals of Earth and its other colonies.

Around the cleared space of the colony, with its metal buildings and barracks, rose towering, steaming fern-jungles, inhabited only by the big, soft-bodied, semi-intelligent bipeds called the Europans. The air that drifted from those miasmic jungles was so damp and hot it choked us as we toiled, and with it came vicious, stinging insects that settled on our perspiring hands and faces...

Zendexor: So there you are; the guards were watching "vigilantly". I could call this the Obvious style. And yet - I could read stuff like this all day. Is there something wrong with my literary taste, then? No - there's something right with it (I answer the question quickly to forestall Stid). The right thing is, to respond to the gift that's offered by the writer - the open-ended promise of the classic Old Solar System.

Raymond Z Gallun, "The Lotus Engine" (Super Science Stories, March 1940); Robert Gibson, Valeddom (2013); Edmond Hamilton, "Mutiny on Europa" (Thrilling Wonder Stories, December 1936); Stanley G Weinbaum, "Redemption Cairn" (Astounding Stories, March 1936); A E van Vogt, "Repetition" (Astounding Science-Fiction, April 1940)

See also Enceladus and Europa - the last OSS worlds?

For Moon of the Unforgotten by Edmond Hamilton, see the Diary entry, False Trail to Europa.

For a comparison between two artists' scenes on Europa see Artistic overlap.