the sunport vista:

zendexor's

oss

diary

2024

The Samuel Pepys of the OSS...

2024 December 22nd:

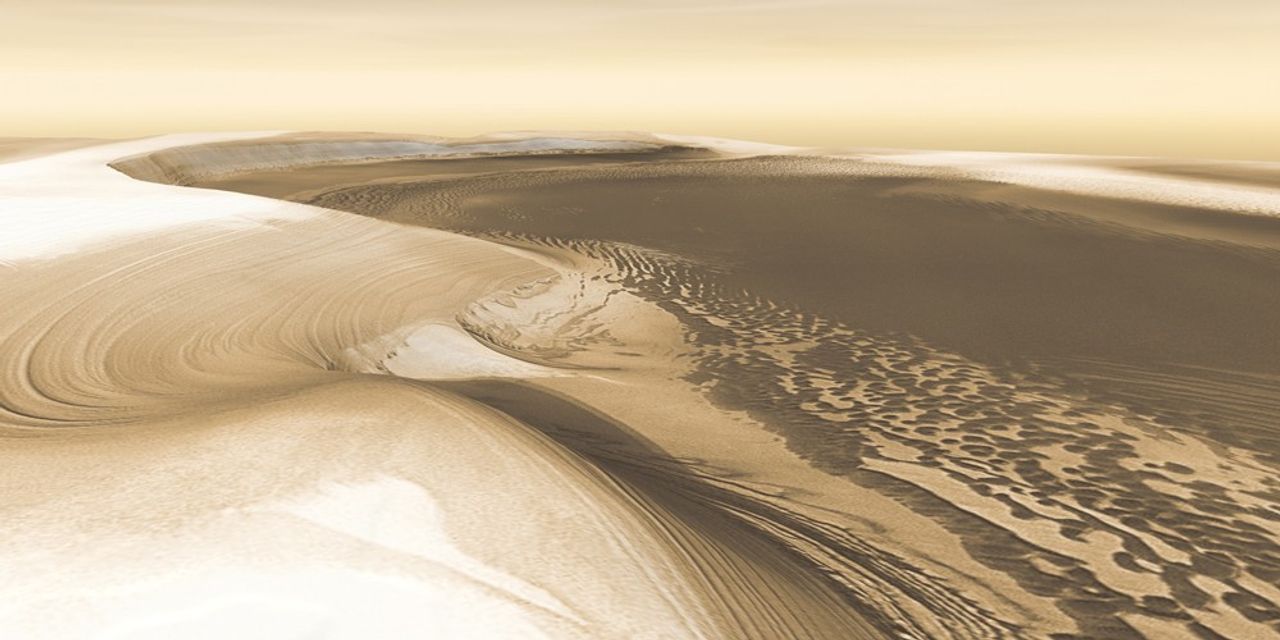

PERFECT SETTING FOR THE CARRION CAVES

How one thing leads to another! I was leafing through an old issue of Sky & Telescope - a magazine I subscribed to for over 30 years, from 1976 to 2008, till I ran out of shelf space - and came across references in one of the 1999 issues to the Mars Polar Lander probe. At that time high hopes were placed on it; I had forgotten what happened to it so I looked online to see. Alas, in the event it crashed on the Martian surface and sent no pictures back. But - while finding this out, I came across a much later picture, or rather composite of several pictures, taken from orbit by the later Mars Odyssey probe.

WOW!!!

Unlike many probe pictures, it's not only interesting, it has charisma, it has character and (metaphorically speaking) "atmosphere" to a stupendous degree. It's more like Barsoom than mere Mars. I can imagine John Carter and Thuvan Dihn plodding along the barrier looking for a way through to Okar, mysterious realm of Mars' frozen North, in ERB's The Warlord of Mars.

Here it is.

Chasma Boreale from Mars Odyssey

Chasma Boreale from Mars Odyssey>> see The Cold White North of Mars.

2024 December 21st:

WELTEISLEHRE AND CREATIVE CRANKERY

When correspondent Lone Wolf sent me an extract to use as a Guess The World scene from a yarn by Nelson S Bond (see Centaur on Themis) I was intrigued by the words,

...once upon a time, thousands of years ago, before Earth's old moon crashed, destroying the civilization then existent, Man knew the secret of spacetravel...

I wondered:

"Earth's old moon"?? Logically, this could either mean a crashed pre-Lunarian satellite,

or the current Moon considered from a far-future perspective in which it

itself has crashed. I thought the former far more likely. With this view in mind, I

then remarked in an email to Lone Wolf:

I wonder about the reference to "Earth's old moon" - I guess this doesn't mean the story is set in some distance future in which our Luna is now gone; more likely it refers to some crank theory that Earth had several successive moons (the sort of thing one reads in Colin Wilson's The Philosopher's Stone etc).

Lone Wolf replied:

This is on of the Lancelot Biggs stories, set somewhere in the XXII century (two centuries ahead, as mentioned in one of the stories). As for the reference to the old moon, I am not sure what exactly he meant, maybe it was the cosmic ice theory of Hans Hoerbiger (published in 1913). I am familiar with it from the books of H.S. Bellamy, very rare now, used copies of which I could buy from internet. It's really fascinating, and although scientifically obsolete in many respects now, it has its valid points (in particular I am convinced that the Moon was indeed a captured dwarf planet and not separated part of the Earth as it's believed now). Hoerbiger may have been wrong about many things, but I also found that he has predicted many ideas, that are now accepted like the existence of things like the Kuiper belt, the Oort cloud, cryo-vulcanism, etc., about which nobody gives him credit and his theory is generally ridiculed now just because later it happened to have the bad luck to be very popular in Nazi Germany. BTW some German rocket scientists like Max Valier and Hermann Oberth had accepted it as scientifically sound in its time and it was also reflected in the science fiction novels of Otto Willi Gail.

I haven't read that novel of Colin Wilson, so I am not sure whether it had the same inspiration...

Crank theories occupy an interesting

literary place somewhere between science and fiction. I generally quite

like them, but I must admit that the idea of demoting our Moon to

merely the latest in a succession of Moons does not appeal to me at all;

it smacks of lack of respect.

As a matter of fact the currently favoured theory of the Moon's origin - the impact of a Mars-sized object called Theia upon a primitive Earth, resulting in a Moon composed of parts of both - is to me quite satisfying aesthetically, allowing us to view Luna as possessing a status part-local, part-foreign, as it were. A real other world, while yet uniquely linked to ours.

Be all that as it may, I invite the reader to look up Hoerbiger and his "Welteislehre" theory, especially if you are researching the limits of academic GAWI...

2024 October 26th:

PLANET OF RESTRAINT

Continuing with my desultory re-read of The Warlord of Mars, I was moved to reflect upon how huge stretches of Barsoom remained unknown for so long. In particular, the frozen north.

...My knowledge of the efforts that had been made by countless expeditions to explore that unknown land bade me to caution, for never had flier returned who had passed to any considerable distance beyond the mighty ice-barrier that fringes the southern hem of the frigid zone.

What became of them none knew - only that they passed forever out of the sight of man into that grim and mysterious country of the pole.

The distance from the barrier to the pole was no more than a swift flier should cover in a few hours, and so it was assumed that some frightful catastrophe awaited those who reached the "forbidden land," as it had come to be called by the Martians of the outer world... [p.78]

- and three pages later the "fabled" yellow men of Barsoom are referred to as

...that once powerful race which was supposed to be extinct, though sometimes, by theorists, thought still to exist in the frozen north...

Imagine the chances of a putative polar civilization on Earth being left in such a limbo of uncertainty! The National Geographic Society, and the Royal Geographic Society, and Ranulph Fiennes, certainly wouldn't leave it alone for long.

Granted that on Barsoom great dangers existed, such as the magnetic trap described in the book, I still feel that it's anomalous - the way on such a fairly small planet, peopled by folk who possess fliers, vast tracts can remain for ages unexplored. We find the same theme in The Chessmen of Mars (with regard to Manator), A Fighting Man of Mars (Jahar and Ghasta), and Llana of Gathol (Horz), to name but some of the regions which are either unknown or at least so isolated as to be very little known until the hero of the narrative reaches them.

Burroughs doesn't give us this plausibility problem in his Venus series. This is because the cultures on Amtor really are isolated for practical reasons - they have no fliers (Carson's one aeroplane is unique), and their misconceived mapping system works against geographic knowledge. But what about the highly intelligent and capable red men of Mars? Why haven't they surveyed their planet properly long since?

Of course it's just as well that they haven't, since the plots of most of the stories depend upon the theme of discovery and the surprises which await the hero in unknown regions. And this felicitous aspect of the plots provides me with the answer to the whole plausibility question.

It transpires that

we don't have to look down our noses at the Barsoomians' geographical

(or areographical) inadequacies after all. Nor do we need to view their

research record as showing incompetence. Instead of showing

incompetence, it reveals - let's have a word that fits better - discompetence.

An alternative, even a rejection, of that plot-nullifying competence

which would have allowed the Red Planet to be exhaustively mapped and

surveyed too soon. To put it succinctly: it shows talent!

You see, the red men's cultural instincts in this regard turn out to be wise after all. In showing proper restraint, in delaying the spoiler effect of premature discoveries, they're as sensible as people who make sure they don't open their birthday or Christmas presents too soon. By holding back until a hero comes along to do it with maximum zip, they preserve their world's zing.

Hurrah for discompetence!

The talent is profound, admirable... perhaps nurtured by some special trace

ingredient in the diet or the atmosphere...

2024 October 16th:

CEREBRAL COSTUMERY IN THE WORLD OF NULL-A

If asked to give an example of a tale which I enjoyed for reasons quite unconnected with the aims of the plot, I could do no better than pick A E van Vogt's The World of Null-A.

My paperback edition of this 1948 novel has a 1970 introduction by the author, in which he spends seven quite interesting pages discussing the ideas of "General Semantics", which obviously are important to him and which explicitly underpin the story.

Now, quite frankly, unlike van Vogt, I don't give a damn about General Semantics, and indeed I can't get at all impressed or excited about courses in how to think - because I don't consider myself or anyone else as an isolated "thinker"; rather, I believe that we're all psychic interactors in processes of awareness that flow through and around and between us. In short, I am a mystic.

Do I then consider the Null-A theme to be valueless in the story? By no means! It's highly valuable, in fact it gives an essential flavour to the book's character. It joins the long list of examples of how authors can unintentionally achieve their positive effects, so that I'm absolutely happy for the narrative to burble on about the cortical-thalamic blah blah. It's a nice bit of wadding that plumps up the cushion on which the reader can settle for his comfortable treat.

Some critics - the author's Introduction mentions these - would disagree, but in my view, through all the complications that pile onto the plot-structure of this notoriously complex novel and threaten to collapse it, the tale begins with a breeze of freedom which carries the reader along to the end.

At the start the hero, Gilbert Gosseyn, apparently finds out that he's lost everything - his memories are false, and he is thrown out of the all-important Games which choose the world's administrators of 2560 A.D. On the other hand, since his previous belief that he had lost a wife turns out also to be based on a false memory -

...Like water draining from an overturned basin, the doubts and fears spilled out of him. The weight of false grief, false because it had so obviously been imposed on his mind for someone else's purpose, lifted. He was free.

What stays in my

mind most of all is the Gosseyn who has been ejected from his hotel and

spends his nights on a vacant lot in the City of the Machine, waiting

for the next thing to happen. An ideal scenario for mystery and

adventure!

2024 October 12th:

ISOLATIONISM ON BARSOOM

Currently re-reading The Warlord of Mars, I'm enjoying it more than ever before. The reasons for liking it less than its predecessor The Gods of Mars

are less strong than they were. The earlier book is still in my

opinion a vastly superior world-building achievement, but the linearity

of Warlord's plot doesn't bother me like it did. So what if

Carter begins at the South Pole and ends at the North, lagging all the

way behind Dejah's kidnappers who are one step ahead of him constantly

until the end? We are vouchsafed many fine sights along the way, and

above all the Burroughs narrative prose style works like a magical lullaby as Carter

shares his thoughts in a childlike stream of consciousness, in which all

his troubles are transmogrified into wonders for the reader.

...I have no stomach to narrate the monotonous events of the tedious days that Woola and I spent ferreting our way across the labyrinth of glass, through the dark and devious ways beyond that led beneath the Valley Dor and Golden Cliffs to emerge at last upon the flank of the Otz Mountains just above the Valley of Lost Souls - that pitiful purgatory peopled by the poor unfortunates who dare not continue their abandoned pilgrimage to Dor, or return to the various lands of the outer world from whence they came...

Stid: Hang on a minute! Hasn't Carter exposed the Dor racket in the previous book? Helium, the number one power on Barsoom, now knows the truth, and so do most of the other front-rank powers. So why isn't the Valley of Lost Souls - the "vale of hopelessness" as Carter calls it - the object of a humanitarian rescue operation? The Heliumite government is, after all, honorable; they could do something with that mighty navy of theirs -

Harlei: It's too soon, Stid. Helium has lost her Jeddak and her princess. The navy needs to be held in readiness in case it's required to rescue them against a conspiracy to revive the power of the therns - that's how I see it.

Zendexor: Fair point, Harlei, but still I see where Stid is coming from and his remarks need a deeper answer. After all, similar objections to isolationist callousness could be made at other points in the series. One outstanding example is the lack of any subsequent official action to wipe out the hideous regime of mad Ghron, the Spider of Ghasta, after Tan Hadron and Nur An have encountered that evil in the course of their adventure in the seventh book, A Fighting Man of Mars.

Stid: Yes, that one is the worst scandal of all.

Zendexor: Well, we don't know; perhaps something was done, something we're not told about. But the main answer I feel bound to give is that the Barsoomian culture is not attuned to organized humanitarian interventions. The closest that they come to it is Carter's efforts in Swords of Mars to stamp out assassination; and that's a telling point because he makes it clear that it was entirely on his own initiative that any measures were taken.

Barsoom, you see, is a world where

story rules. The environment is geared to adventure, first and

foremost. Barsoomians don't really hanker after a world order that is

zealous for human rights; in fact I doubt they could grasp abstract

"rights" as a concept at all. They know about justice, but to them

justice is not abstract - it is the maintenance of customary virtue and

honour. And this lack of over-riding "rights" is actually part of the

enchanting spirit of the series. It's what "makes that world go round". For purposes of the production of

stories to tell, it works like a charm, the effect of which is that awkward questions

like yours, Stid, at any rate in their own terms, are given permission not to be answered.

All

in all, the Barsoom series provides endless world-building lessons,

teaching not only the things that a writer needs to do, but also things

that (given the right attitude) a writer need not do. That's the big secret!

2024 October 11th:

JOHN CARTER BLUNDERS AGAIN WITH THE BARSOOMIAN YEAR

I seem to remember (it's a long time since I read the book) that Carter in The Gods of Mars forgot that the Martian year is a lot longer than Earth's.

Just today I was looking at the next volume, The Warlord of Mars, because though it's not one of my favourites I felt in the mood to immerse myself in Burroughs' prose style and colourful description, which are well up to par in this book. And on the very first page I came across another of Carter's astronomical blunders!

...Six hundred and eighty seven Martian days must come and go before the cell's door would again come opposite the tunnel's end where last I had seen my every-beautiful Dejah Thoris.

Spot the error? The Martian year is 687 Earth days long. Not 687 Martian days, because the Martian day is about half an hour longer than Earth's. The number of Martian days in a Martian year is about 668.6.

It's lucky for John Carter and for his incomparable Dejah that he overheard his enemy Thurid say he'd discovered a way in to the Temple of Issus before its annual revolution was completed. If Carter had counted on the 687 days he'd have found he was 18 or so days too late for the rescue.

One

hears mention of "the luck of the Irish" but in this case it's "the

luck of the hero". And a lot of the luck depends on the identity of your guardian angel, or rather, your guardian author. By that I mean, if you're a fictional protagonist it's important to

have an author like ERB, rather than (say) Thomas Hardy, writing your story.

2024 September 24th:

BLUE MARTIAN VEGETATION

From page 156 of Lin Carter's The City Outside the World (1977):

...With the kind of sunlight that reaches Mars, blue vegetation can photosynthesize just as well as green does back where you and I come from...

Confession: my best

O-level exam result, back in 1970, was for the "Physics with Chemistry"

paper, not because science was my best subject, but for the opposite

reason, that it was my worst - which meant I knew I had to bestir myself

to work at it (the corollary being that my worst result was for my best

subject, English Literature). As for biology, I didn't even take that exam.

Given my ignorance of anything to do with the life sciences, I have no idea how true Lin Carter's comment about blue photosynthesis on Mars may be, and I don't feel like bothering to try to check it out... because its value, to me, lies in its quality of scientific patter. It need not bear close scrutiny; it need only act as a sort of feeder-tube that links the setting and the plot to realism via the murmurs of scientific verbiage that trickle along the tube. The murmurs amount to an incantation, summoning the reassurance that the idea of a rule-based scientific universe is being respected.

Is a literary law being broken, though? Shouldn't Martian plants be red, as in Wells' "Red Weed"?

My view of this serious issue, is that so long as the ochre deserts hold sway, we can allow the plants to be some other colour.

Note added 26th September 2024:

Correspondent

"Lone Wolf" kindly sent me some information as a follow-up to the Diary

entry - with regard to a pioneering Russian astrobotanist,

Gavriil Adrianovich Tikhov. LW writes:

Back in the 1940s-1950s one Russian astronomer - G. A. Tikhov - researched the subject of life on other planets; he compared the reflecting spectra of plants living in conditions similar to those on Mars in the Arctic, on the high plateaus of Pamir, etc., and speculated that the vegetation on Mars should have a blue colour, while on Venus it should be yellow and orange. He even developed a new speculative discipline called "astrobotany", but after his death his observatory and astrobotanical laboratory were dismantled and all these things forgotten. I think Lin Carter mentions him in one of his Martian novels... There aren't any translation of Tikhov's original works and I found only several abstracts from articles which give some general information about him and his "astrobotany"... I think Clarke may have mentioned him in some story about Venus.

2024 September 2nd:

ASTROLOGY AND A WARM SATURN

"Guess The World" contributor Lone Wolf added a comment to his latest excerpt, with regard to an apparent inconsistency between supposedly interlinked tales by John Russell Fearn. Outlaw of Saturn sets a scene on a habitable version of the planet's surface (see Plantation on Saturn); elsewhere however we meet the idea that the Saturn system of moons has been kept warmly habitable by radiation from a presumably molten version of the Ringed Planet; Fearn having written that

...Titan is "...a little desert island of a world, bathed in the torrid heat of Saturn 770,000 miles distant. Unlike Jupiter, the ringed world has cooled less swiftly and pours its warmth on its whole retinue of moons", which makes it not very probable that Saturn could be inhabited... I am not sure whether the author was just careless about the background or the statement about the heat of Saturn shouldn't be taken too literally and it doesn't suppose to mean that the planet is still in a molten state. Anyway, a hot Saturn, unlike Jupiter, somehow doesn't seems fitting to me, and this is not only because of the RSS Saturn, but also because of its astrological archetype, which makes me associate it with cold and coldness...

This reminds me that I don't recall ever having specifically discussed the theme of astrology on this site. And yet, why not? By implication, "astrological archetypes" may have plenty of relevance for literary archetypes.

This bond comes to the fore in the great chapter "The Descent of the Gods" in C L Lewis' That Hideous Strength. Music, also, provides a key example: old, cold, and slow, are the impressions one gains from listening to the beautiful Saturn section in Holst's suite The Planets, based on astrological rather than astronomical ideas. That mood indeed firmly takes sides against any molten version of Saturn, since heat naturally implies energy and molten heat easily goes with energetic violence.

My attitude to astrology is an odd mixture. I don't think it's rubbish (undefined paranormal cosmic influences may well abound) but I get put off by the preoccupation with astrology shown by so many people who couldn't care less about astronomy. In fact they often confuse the two.

For me, astrology's big fault is its concentration on relevance to our lives. Yuck! Give me a break from that! Why abandon astronomy's main virtue, namely that it gives us a holiday from human pettiness, and takes us out of ourselves into a wondrous infinity?

Of course a wise astrologer might object, "No, we don't diminish the wonders, on the contrary we tune you into them - we explore the link we have with them." But as I pointed out a few lines ago, I've met so many people whose interest in astrology seems to preclude any interest in stars and planets and moons for their own sakes; people who in fact have no urge to learn even the basic facts of astronomy.

Patrick Moore trenchantly opined that "the only thing astrology proves is that there's one born every minute". I don't go as far as that, keen fan though I am of Patrick Moore. But give me an astronomical rather than an astrological text to pore over, any day.

...One more thought about a warm Saturn. Maybe it doesn't need to be molten in order to warm the moons. Instead of heating them by radiation, which has to obey an inverse square law and thus be intense at its source, how about conduction?

Stid: Conduction through what, may I ask?

Zendexor: Through any old excuse. Some etheric medium, maybe peculiar to the Saturn system. Who knows? All you need for an OSS scenario is a decent helping of scientific patter. That's the glory of this sub-genre: science is the obedient servant of the story and so duly comes up with the right incantation to provide it with the best setting.

2024 August 28th:

MISSING OUT THE GREATEST CREATURE-OF-THE-VOID

This note is primarily a salve to my conscience. I wouldn't wish any reader to miss out on Fred Hoyle's The Black Cloud (1957) just because (due to the eponymous entity's enormous size) the novel wasn't given a full treatment in my recent page on Creatures of the Void.

I'm currently re-reading The Black Cloud for the umpteenth time and am hugely impressed with it as a story, and by the scientific discussion which is part of the story, and the observatory scenes, and the absorbing political interactions. Worth repeated readings, in which one is bound to get more out of it each time. For instance, this time round I've properly understood the reasoning behind the discovery of the Cloud's intelligence, which I don't remember having previously grasped.

My advice is - don't waste a second on the stuff I wrote about in the COTV page, before you have read Hoyle's novel.

2024 August 25th:

VIRTUALLY IMPOSSIBLE TO PIGEON-HOLE

Cosmic Teletype by Carl Jacobi (Thrilling Wonder Stories, October 1938) intrigues me. It has an original way of being absurd. I'll list some of its points (spoiler alert).

The protagonist Joseph Rane has had a brain operation - which has something to do with how he manages to get news from outer space, though I feel that I'd need a brain operation myself in order properly to understand the practicalities involved in this the story.

He is eventually double-crossed by aliens from an extrasolar planet called Lirius, which is at war with our system's own world Uranus.

The tale refers to the "King of Uranus". I find that really cute. Analogies with the Trojan War also come into it.

Finally, Rane succeeds (at the cost of his own life) in averting the conquest of Earth by the treacherous Lirians whom he had helped.

Now, let me stress that this tale is not written in a jokey manner. If it were, it would be unreadable. Perhaps it's possible to pigeon-hole it after all: we could say that it belongs to a rare sub-genre called... seriously-cutely-mad? Add a satirical element and it could have been something by Philip K Dick.

2024 August 24th:

ADDENDUM TO "A SPACE-BOOT IN BOTH CAMPS"

The entry in the Diary for 13th June discussed a treatment of the Martian Canals theme in which Lin Carter combines the glow of legend with some of the flavour of scientific modernism. That discussion included a quote from The Man Who Loved Mars (1973).

I'd like here to add, for confirmation and comparison, a similar but not identical treatment in the same author's The City Outside the World (1977), which appeared four years further into the age of space-probe-inspired realism, but still managed to preserve the previous novel's links with nostalgia. From pages 51-2:

When Mars began to dry up as the free water vapor in its atmosphere escaped in ever-dwindling amounts into space, the crust of the planet had shrunk and cracked, forming a network of long, geometrical lesions in the surface. Into these titanic ravines the shrinking oceans, or what was left of them, had drained. And over succeeding ages the Martian vegetation, adapting to ever-dwindling supplies of moisture, had taken root along these fissures, forming thick belts of hardy growths whose root systems delved down for miles into the pockets of moisture trapped within the bowels of the planet.

It was these broad strips of fertile vegetation the Earth astronomers had mistaken for artificial waterways. Only some of them, like Nilosyrtis, had once been the beds of primordial rivers, and only a very few showed any signs of having been engineered by human hands. While it was now thought that a few of the old canals had actually been "mined" for water with immense rigs which had probably resembled the oilwells of Texas and Oklahoma, most of them were natural phenomena, and none of them bore even the slightest resemblance to the super Venetian canals which had webbed the planet from pole to pole in the imagination of Earthsider astronomers and fiction writers two centuries ago...

A novel written in a pose of cunning pseudo-realism, published the year after the Viking probe landings! How gladly, nowadays, we'd settle just for "broad strips of fertile vegetation" in lieu of waterways.

2024 August 22nd:

MARTIAN YEARS / EARTH YEARS - A MINOR GRIPE

One of the virtually immortal Ibim - the native Martians in Edmond Hamilton's Planet of Exile (Space Travel, July 1958), whose minds migrate from body to body - bestows on an Earthman a vision of Mars' distant past:

Farrow gaped, incredulous...

He looked upon a green and verdant Mars. Down from hills not yet worn away by time sloped the fertile lands, and the river that ran from the hills washed the edge of a fairylike glass city. And of a sudden he was in that city, among the Ibim. But these Ibim were not furred, their bodies were covered with golden down. Their glittering air-fliers buzzed like dragonflies, going and coming between cities far away.

"I lived in that city," came Tlaa's thought. "Not bodily - the body of the Ibim who lived there is dust these half-million years, but his memories are my memories, passed down through all the generations..."

And so on. Classic stuff. Only - a literal chap like me, a stickler for historical accuracy, wants to know whether "years" means Martian years or Earth years. It depends how much Tlaa's thought has been translated into Terran terms.

The same problem occurs in the Barsoom books, with regard to some statements about the history of Mars and the ages of Martians. And, be it noted, John Carter himself got dangerously confused in the second and third book, when due to a deadline in the Temple of Issus the meaning of "year" was a matter of life and death for Dejah Thoris.

About Tlaa's "half million years", about the Barsoomian "thousand year" lifespan, about jeddak O-Tar's reign of 433 years in The Chessmen of Mars... about the 23,000 years of the Tower of Thavas, or the 23 million years since the creation in the Valley Dor... What to think, what to think...

Such a preoccupation by a slightly irritated reader is of course a compliment to the authors whose works pack sufficient punch to arouse such concern!

2024 August 8th:

BORDERLINE SETTINGS

As a gauge of how closely our mentalities align, I invite you to guess what the following scenes, one on the Moon and the other on Jupiter, share in common.

The first is from The Lunar Pit by Myer Krulfeld (Thrilling Wonder Stories, June 1940):

"...Li-Kar

was built aeons ago, when my people realized that in a comparatively

short time the Moon would lose its air. They dug a chasm almost five

hundred miles deep on the side of the Moon away from the Earth, where

the Earth's gravitational pull would reinforce that of the Moon, even if

slightly. The stronger pull sucked most of the remaining air on the

Moon into the pit, preventing its escape..."

The second is from Passport to Jupiter by Raymond Z Gallun (Startling Stories, January 1951):

...The

fearfully compressed atmosphere was calm. His armor rose and settled

rhythmically as in an ocean swell. A faint rustling like that of water

reached his ears...

...Causing the arms and legs of his armor to move gently he swam forward through the thick stuff around him. It seemed to consist of a combination of fluid and slush - liquefied gases, part of which had even congealed...

...It took fifteen minutes more of paddling through the slush to get really close to the source of the light ahead...

I call both of these visions "borderline settings" because each one straddles two categories of scene in a manner which is important to me.

Plenty of lunar tales describe Lunarians who live underground, in caverns. This always disappoints me. I understand it's a useful dodge if a writer is looking for an excuse to portray a cilivization that belongs to an apparently dead world: you discover a cavern and, gosh, it's amazingly peopled! Convenient for the story, of course; yet I much prefer the vistas provided by surface settings, without which (to me) the place hardly seems a proper world at all. Wells in The First Men in the Moon got round the problem to some extent by making the surface of his Moon alive in the day and dead at night, yet even so his Selenites live mostly underground all the time, with only the herders of moon-cows venturing to the surface, if I remember correctly. Other authors get round the dead-surface problem by writing about an ancient inhabited Moon when that world had a proper atmosphere (remember, this is the OSS: perfunctory nods in favour of scientific realism are enough to do the trick).

Consider, then, The Lunar Pit.

Krulfeld, in the passage quoted above, cleverly combines the ideas of depth and

surface. His 50-mile-deep lunar pit is open to the sky, hence part of

the surface, but is so anomalously deep that it enjoys the realistic

advantage of the caverns. That's why I consider it a "borderline

setting": it straddles two advantages, that of minimum plausibility and

that of scenic openness.

Now for Gallun's Jupiter. It has a surface, of sorts. Enough of a definable surface, that the protagonist in his armor does not sink further down but is able to wade along. However, the references to wading, paddling and slush manage successfully to blur the image of a normal surface. They thus add a smudge of a hint of the real Jupiter, where no surface exists at all. This imaginative link, for me, is what combines the flavours of OSS and RSS, and encourages me to suspend disbelief rather more mildly than (for example) I have to do when reading ERB's good old Skeleton Men of Jupiter!

Not

that I mind having to suspend disbelief to any degree necessary to

enjoy a story. But the "borderliners" do sew an interesting hem onto

the repertoire.

2024 July 31st:

TANTALISINGLY WRONG FOR A GUESS-THE-WORLD SCENE

I had begun to type the following Mercurian scene into Guess The World and then I saw that it wouldn't do, so, rather than abandon it, I shall work it into the Diary instead:

Off to the left was the eternal glorious sunset, which would brighten or darken somewhat during the course of the Mercurian year… because of the librating wobble of this small fantastic world in its eccentric orbit. Dust, blown high in the thin atmosphere, made that sunset so gorgeous.

Off to the right were the light-gilded peaks of the ice mountains. Ahead lay the mossy plain of the Twiligt Belt, stretching between two terrible deserts of furnace heat and spatial cold. The plain was dotted with boulders and weird vegetation that looked half like cactus, half like living crystals. Behind, under its great transparent airdome, lay Mercury City, colonial metropolis of the Earthly colonists.

Nord heard Joey Harwell say through their oxygen-helmet radios “Hurry up Pop. We’ve got to reach Korolov, capital of the extinct Lubas, in an hour to be on schedule. We can have a rest there and then start climbing the mountains toward the Dark Side Station.”

I dare say you can immediately see why it's no go for GTW. The give-aways and clues are so embedded in the sentences that to [..........] them would mean there'd be almost no scope left for guesswork.

Besides, in this strange story - Passport to Jupiter by Raymond Z Gallun (Startling Stories, January 1951) - the scene is not actually happening on Mercury, but is a kind of mental recording of an adventure. Decadent Earthlings are fed on such dreams, some of them recordings of real things but nevertheless contrived (note the artificiality, the heavy-handed explanatory style of Harwell's phrasing).

It's a long, complicated tale, rather heavy going but I'm enjoying it. Certainly it's proof that the pulps were not always feeding escapist pap to their readership (though far be it from me to knock escapist pap). Gallun was a thinker, and some of his tales succeed on both artistic and intellectual levels; this one however is more of a curiosity than a masterpiece.

But the little Mercurian vignette quoted above is, to me, archetypically poignant. Think of that "eternally glorious sunset" in one direction and those "gilded ice mountains" in the opposite direction; and combine them with the boulder-dotted plain in between, with its cactus/crystal growths. And the "extinct Lubas" capital somewhere close by.

What more potential could one ask of a vision of OSS Mercury?

2024 July 26th:

ANOTHER "MI-" TOWN

Lone Wolf, researcher and contributor to Guess The World, has added a coda to my remarks about Middletown and its like in the previous Diary entry:

Yesterday,

while browsing among the old pulp magazines online, I came across one,

which I've never heard of before - Satellite Science Fiction, and this

issue from 1956 contained a story by Philip K. Dick, entitled A Glass

of Darkness, which turned out to be an earlier version of his novel The Cosmic Puppets: https://archive.org/details/Satellite_v01n02_1956-12_cape1736/page/n5/mode/1up?view=theater

...I

read it back in the 90s... but I had completely forgotten that the name of the place

where it happens was Millgate, Virginia. I don't know if it's a real

place or not, but here is another example of an ordinary provincial

town, where strange things happen and its name begins with "Mi-": they

seems indeed to be quite popular in the science fiction! (I've always

liked such type of stories, which start from settings, so ordinary, that

they seem like the last place where something interesting may happen,

and then somehow go to fantastic and unusual events.)

On receipt of this email my first reaction was to search online for Millgate, Virginia. Alas, it doesn't seem to exist, as far as I can discover. But perhaps some day it will! Perhaps PKD fans will cause it to exist, like the eponymous Colorado town in James A Mitchener's Centennial - purely fictional when the novel came out in the 1970s - was later brought into being (by means of a renaming, I assume, rather than an actual founding).

The theme of the impingement of the fantastic on

an ordinary village or town is so attractive that I have long had the

idea of doing a page on it, though I haven't yet thought of a title.

Writers such as L P Davies and J T McIntosh, whom I have not discussed

much on this site, ought to be represented alongside stalwarts such as Clifford Simak and Eric Frank Russell.

But it's unlikely I'll manage to produce such a page any time soon, since it will involve such a lot of re-reading and planning to do justice to the topic.

2024 July 18th:

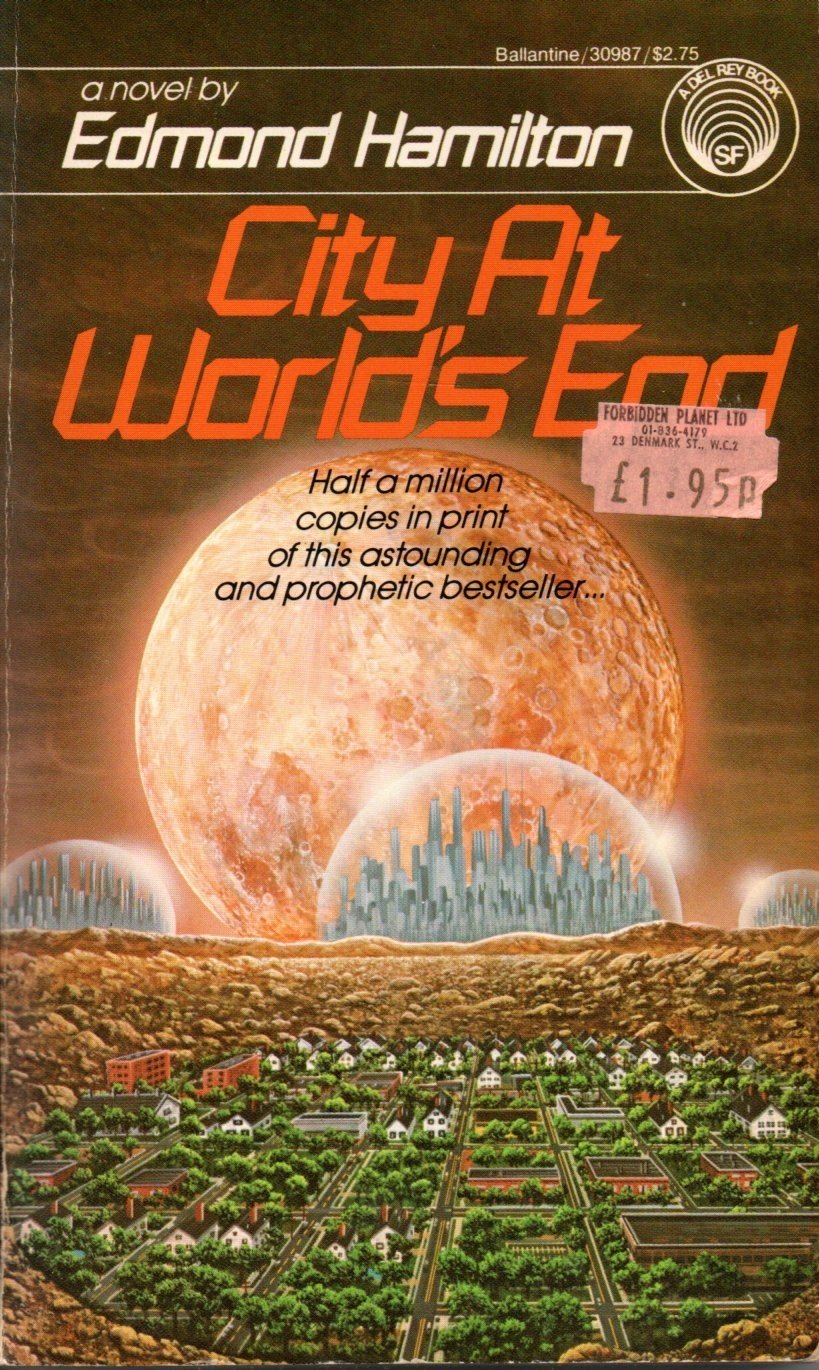

LIFE MATCHING ART: CITY AT WORLD'S END

It hardly ever happens - in fact this is probably the first time - that I find a topic in contemporary party politics worth commenting on here.

Shows the label for "Forbidden Planet Ltd" which is the shop in London where I bought the book on 19th July 1993. The shop (now in Shaftesbury Avenue) still thrives, bigger than ever.

Shows the label for "Forbidden Planet Ltd" which is the shop in London where I bought the book on 19th July 1993. The shop (now in Shaftesbury Avenue) still thrives, bigger than ever.I've just heard that the USA's Republican Party's nominee for Vice-President is someone who hails from Middletown, Ohio.

MIDDLETOWN! clangs the bell in my head. Hey, that's the vividly portrayed small town that gets blasted millions of years into the far future in Edmond Hamilton's gripping 1951 novel, City At World's End!! I had always assumed it was an invented place - the name chosen to suggest utter ordinariness, to provide dramatic contrast with its fantastic fate. Yet now I hear that the name refers to somewhere real, in Hamilton's home state.

I dare say I should have known better than to assume it was purely fictional. After all, Simak's unforgettable portrayal of equally ordinary Millville in All Flesh is Grass (1965) is based on a real place in Wisconsin; in fact it's where he was raised, if I remember correctly; and yet "Millville" sounds fictional, like "Midwich" in John Wyndham's The Midwich Cuckoos - a village which, alas, is indeed purely an invention of the author, though it seems utterly real the way he describes it.

These facts tempt me to say: those of you living in a place beginning with "Mi- ", you'd best keep a look out for unusual events.

2024 June 20th:

CYCLE-ROUTE GUIDES TO A MARTIAN INVASION

While doing a bit of online research for the Gazetteer, in particular for Maybury Hill which is where the narrator of The War of the Worlds sees his first Martian Fighting Machine, I found a reference to a cycle guide to the area.

Currently, it seems, one can read the guide online. I've had a look at it and it appears perfect for its purposes. It reminds me of a similarly loving online tribute/guide to the real-world English locations mentioned in The Day of the Triffids; both books inspire the effort to be made, for Wyndham, like Wells, is superb at making the reader's mind travel to where the action is and see the place through the narrator's eyes.

Are there, I wonder, equivalent guides to other great sf authors and their stamping grounds? Well, there's H P Lovecraft's New England, which you can explore in the 800+-page, lavishly illustrated New Annotated H P Lovecraft, edited by Leslie S Klinger, which my brother gave me back in 2017 as a birthday present. That is on a far vaster scale; you could hardly carry it in your knapsack - I recommend it more for browsing in an armchair, preferably with a cushion to prop up the book while you lose yourself in eldritch immensity.

2024 June 13th:

A SPACE-BOOT IN BOTH CAMPS

The boundary between the Old Solar System and the Real Solar System is clear enough - the OSS is based on pre-space-age ideas, the RSS on what, in the Space Age, is scientifically believed.

It's possible, though, for writers to create works intended to straddle that boundary. Irrespective of their degree of success, I find such attempts interesting.

Let's class them in two kinds - the backward-gazing RSS and the forward-gazing OSS.

First: the reluctant, backward-gazing, boot-dragging realists:

John Varley's In the Hall of the Martian Kings (1976) and Arthur C Clarke's Transit of Earth (1971) are both space-age tales set on Mars. They are written by modernists who, despite their realism, hanker so strongly after the old-style Mars that they do their utmost to stretch backward towards the idea of advanced Martian life, like clever lawyers looking for loopholes to avoid a conviction.

Clarke's

story was written after the discouraging results from the first flybys, Mariners 4, 6 and 7;

nothing daunted, the author conjures up future probes which provide evidence more to his liking:

...Those moving patches on the orbital photographs. The evidence that whole areas of Mars have been swept clear of craters, by forces other than erosion. The long-chain, optically active carbon molecules picked up by the atmospheric samplers.

And, of course, the mystery of Viking 6. Even now, no one has been able to make any sense of those last instrument readings, before something large and heavy crushed the probe in the still, cold depths of the Martian night...

And, don't talk to me about primitive life forms in a place like this!

Anything that's survived here will be so sophisticated that we may look

as clumsy as dinosaurs...

Varley's story, written later still, well after the Mariner 9 orbiter's survey, seizes the excuse offered by long-term orbital fluctuations (a theme likewise exploited by Ian Watson in his 1977 novel The Martian Inca). Varley's In the Hall of the Martian Kings sets out the scientific background thus:

"You've heard of the long-period Martian seasonal theories? Well, part of it is more than a theory. The combination of the Martian polar inclination, the precessional cycle, and the eccentricity of the orbit produces seasons that are about twelve thousand years long. We're in the middle of winter, though we landed in the nominal 'summer'. It's been theorized that if there were any Martian life, it would have adapted to these longer cycles. It hibernates in spores during the cold cycle, when the water and carbon dioxide freeze out at the poles, then comes out when enough ice melts to permit biological processes..."

Terrans landing on Mars unwittingly trigger these processes ahead of schedule, which will allow an encounter with Martians.

Like the Clarke scenario, the Varley one seems far-fetched but not impossible, and so long as it's not impossible, we can class it as RSS not OSS.

Second, let's take a look at the opposite "straddling":

Here, instead of realism weighted by nostalgia, we consider the converse: that's to say, late-period OSS writings which are influenced enough by space-age discoveries that the reader is able to have the sweetness of his nostalgic brew sharpened with some astringent drops of modernist, real, space-age science. Not that the reader's critical faculty is really fooled. Yet the tincture of realism is a shade stronger than that provided by the OSS' traditionally perfunctory nods towards science. For these new nods are Space-Age.

The perfect example is provided by Lin Carter's quartet of lost-race Mars novels, collectively called The Mysteries of Mars. The first to be written, but the latest in internal chronology, is The Man Who Loved Mars (1973). The other three are: The Valley Where Time Stood Still (1974), The City Outside the World (1977), and Down to a Sunless Sea (1984).

In some moods I can enjoy them as novels, in others as mere curiosities. Either way, one opinion which I hold steadily is that they are vastly better than Carter's frustrating pseudo-Burroughsian Thanator (Callisto) series.

In The Mysteries of Mars, Carter makes a noticeable effort to imagine how space-age data and the romantic old Mars might be reconciled. He can't actually convince - or he convinces only by collusion with the reader's ability to suspend disbelief - but the fact that he tries at all is what gives the series its flavour. Juxtaposition of denial and affirmation is the game he plays: a technique which you can view either as a sort of con, or as a praiseworthy attempt at psychological preparation.

...The

shaggy border of the canal shrank behind us, merging in a

purplish-brown line that seemed to stretch across the world from north

to south with such perfect precision that you could swear it had been

inked across the dustlands with a mapping pen. The canals of Mars are

really patchy, broken areas of low, thick-leaved shrubs and very dense

moss which flourish - if that's really the word for such marginal

survival - along subsurface crustal lesions where moisture has been

trapped for ages by sheets of solid bedrock. From a distance, due to

optical effects, these fertile stretches of vegetation seem to take on

an astounding regularity which suggested to early astronomers that they

were vast artificial waterways...

- The Man Who Loved Mars, p.44

This stuff is not quite the Neo-OSS about which I've written elsewhere: that's to say, tales which simply ignore Space Age findings. There's an infinite literary future in the full-blown, defiant NOSS, whereas I suspect that Lin Carter's sort of balancing act will not be repeated outside the early decades of the space age - unless, that is, it sprouts its own tradition of hybrid tales!

[See also the Addendum in the Diary for 24th August.]

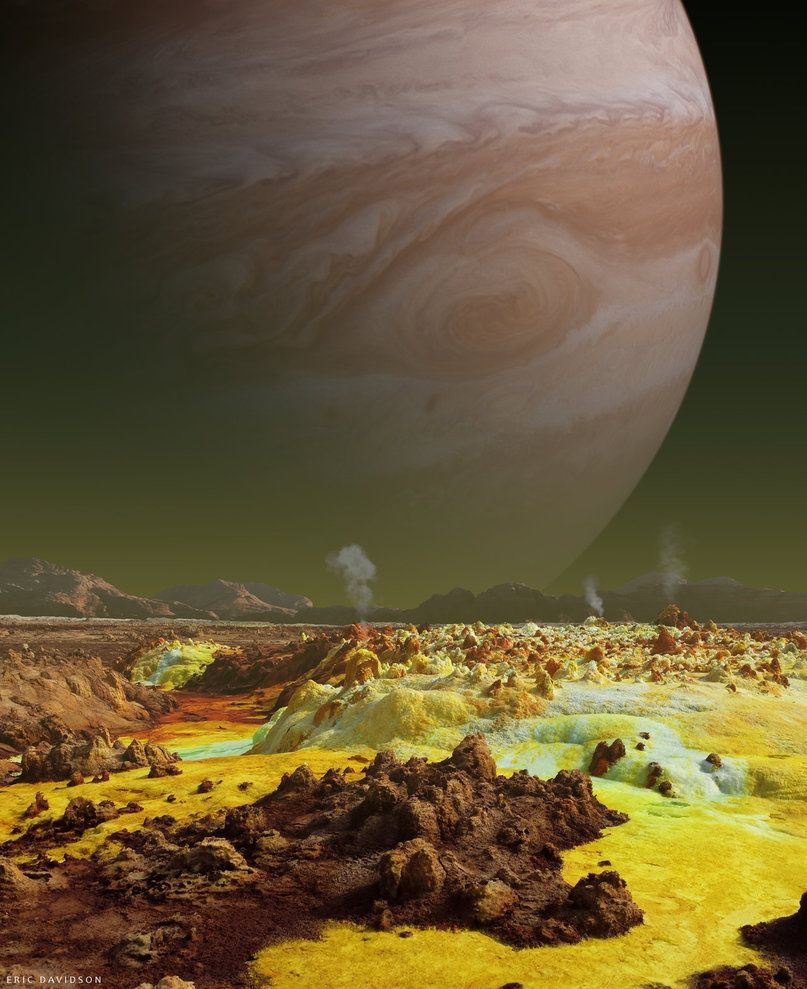

2024 May 20th:

BEYOND THE 'LOW WORLDS'

The sub-genre of Old Solar System literature tends, naturally, towards habitability of settings. But habitability for whom? We could reasonably suppose that the gas giants may be homes to beings which are not what we'd recognize as life - after all we really do not know what might be out there - in which case the OSS and the Real may overlap, even now, in the outer regions of the System.

This fringe-overlap unfortunately can't provide a setting

for human adventure on the giant worlds in the style of Captain Future, or of John Carter's final adventure, Skeleton Men of Jupiter, or of Suddaby's Prisoners of Saturn - all of which exemplify my own favourite style of literary treatment of the outer planets.

Yet

a few writers have successfully straddled the boundary by plotting some means of transference of consciousness whereby a human protagonist can

experience (for example) a Jovian setting in a Jovian body. Think of Clifford Simak's Desertion, or of Poul Anderson's Call Me Joe. These are favourites too; tales of unforgettable brilliance.

Could one go further, and write of a mind-swap with some entity that does not possess what we'd call a body at all?

For some time I've been intending to mention the following snippet of conversation with the Green Lady in chapter five of Perelandra:

"What do you know about other worlds?" asked Ransom.

"I know this. Beyond the roof it is all deep heaven, the high place. And the low is not really spread out as it seems to be" (here she indicated the whole landscape) "but is rolled up into little balls: little lumps of the low swimming in the high. And the oldest and greatest of them have on them that which we have never seen nor heard and cannot at all understand. But on the younger Maleldil has made to grow the things like us, that breathe and breed."

If

someone were to write a tale in which an explorer by some means went

that far, the result would go way beyond the sub-genre of the OSS; yet

perhaps the inspiration could be traced back here...

2024 May 12th:

CLARKE MISTARGETS THE LAKE OF DEATH

In The Challenge of the Spaceship (1959) Arthur C Clarke included an essay on lunar nomenclature, "The Men on the Moon", which in my view is unworthy of a writer who (however superficial his metaphysics) had plenty of poetry in his soul.

He admits that names like "Ocean of Storms" are "picturesque", but the main drift of his argument is a tut-tutting one.

...It

is unfortunate... that so many of these names are fanciful, cumbersome

or downright inappropriate. Since all the major formations on this

side of the Moon have already been labeled, it is probably too late to

do much about them except in the most extreme cases. (Future lunar

colonists may take violent exception to living in Hell, the Marsh of

Putridity or the Lake of Death.) The least we can do, however, is to

make sure that the maps of the other side are less medieval and

inconvenient...

...Indeed, and therefore we need not wonder why the Farside names are so much more boring!

Clarke is quite interesting on the Jesuit astronomer, Joannes Riccioli of Bologna, who published his lunar map in 1651. But despite Fr. Riccioli's scheme being "a consistent one", Clarke clearly finds its survival something of an embarrassment. For example, with regard to the lunar maria, although

...Riccioli knew perfectly well that they were dry plains, he christened them seas... oceans, lakes, bays and so on. In the actual naming he really let his imagination go, being strongly influenced by astrological ideas and the notion that the Moon's first quarter promotes good weather while its last quarter brings storms and rain... [Clarke then lists a lot of the names, ending his paragraph thus:] We can be slightly thankful that, somewhere in the last three centuries, Riccioli's Bay of Epidemics and Peninsula of Delirium have dropped by the wayside.

Oh, I don't know. I concede that "Peninsula Deliriorum" as an address would be a bit of a mouthful but you could shorten it while retaining some of its zest. That's what happened to plenty of place-names in my own country after all - consider how "Beorhthelmes tūn" (Beorhthelm's farmstead) was eventually shortend to "Brighton".

How about Pendeliorum...?

2024 May 8th:

AN EERIE MOMENT IN THE BODLEIAN

Though never a student at any Oxford college I managed to obtain permission during 1977-78 (when I was lodging in Oxford) to use the Bodleian Library. And my most vivid memory from there is of the occasion when I ordered from the stacks a copy of Fontenelle's Discourse on the Plurality of Worlds (1686), in the original French. It may have been an eighteen-century reprint but it was nonetheless a very old little book, in perfect condition, and I felt privileged just to be allowed to handle it.

Moreover the text turned out to be easy to follow, the French simple and clear. It's a charming sedate dialogue between a gentleman and a lady concerning the possibility of life on other worlds. One detail amazed me above all and has stayed in my memory. I certainly can't remember the exact words so I can only try to convey the gist very loosely. The dialogue had turned to the topic of the moon.

LADY: But surely we can never know whether these ideas are true. After all, the Moon is forever out of our reach. No one will ever be able to go and see.

GENTLEMAN: With regard to that, I am not so sure; I don't think we can quite rule out the possibility that one day people will be able to reach the Moon.

My awareness that this little passage had been composed way back in the seventeenth century, induced in me a degree of awe, that I have never forgotten. We'll never know, this side of the grave, what was in Fontenelle's mind. His hunch seems all the more valid as prophecy, in that he did not outline any speculation about how such a voyage might be accomplished. He did not know, and did not pretend to know; all he did know was, that Time stretches vastly and the future is likely to be astonishing.

And what we can know from Fontenelle's remarkable guess, is that some of our own way-out prognostications may eventually hit the bull's eye!

2024 May 5th:

MISLEADING BEAUTY

Confession time.

I've just finished a podcast in which the Roll Off A Tangent team discuss Brightside Crossing by Alan Nourse. As a further bit of contemplation I then re-read the page on this site which concerns that story. It has struck me that one thing I neglected to mention was the strong impression made on my young self by the beauty of artists' impressions of Dayside Mercury. The baked rocks - yellow in the story - and lava-filled cracks make for good dramatic art. But the beauty is deadly. To go to a place like that for real would be to meet with suffering and death. Yet my naive younger self - very young indeed I was, just a little boy seeing those pictures - was so captivated by the colours, at such a deep mental level, that when I grew up the captivation remained in force, so that if the actual opportunity had been offered to me to go to a Mercurian Dayside for real I might well have been daft enough to take it up!

End of confession.

(I shall announce the podcast as usual when it becomes available.)

2024 May 4th:

MULTI-GENETIC WORLDS

One of my pleas for themed stories (see others in Tales Unwritten).

I was browsing in my Weinbaum collection and came across this bit of Redemption Cairn:

...In the ephemeris, Europa is dismissed prosaically... For an astronomical ephemeris isn't concerned with the thin film of life that occasionally blurs a planet's surface; it has nothing to say of the slow libration of Europa that sends intermittent tides of air washing against the mountain slopes under the tidal drag of Jupiter, nor of the waves that sometimes spill air from valley to valley, and sometimes spill alien life as well.

Least of all is the ephemeris concerned with the queer forms that crawl now and then right up out of the air pools, to lie on the vacuum-bathed peaks exactly as strange fishes flopped their way out of the Earthly seas to bask on the sands at the close of the Devonian age...

Life may have originated more than once on Earth, although I gather than all current terrestrial life is related. But life must surely be even more likely to originate and to survive in unrelated phyla on worlds which possess habitable areas that are cut off from one another.

Weinbaum's Europa, and the Mercury of isolated valleys described by Leigh Brackett in Shannach - The Last, and perhaps the Saturn described by Arthur K Barnes in one of his Gerry Carlyle stories, are likely scenarios for such multi-genetic development. The theme isn't exploited to the full - the authors had other fish to fry - but what brimming possibilities in this bounteous idea! (Not the first time I've suddenly been overcome by such excitement - see last year's Diary entry Pockets of atmosphere.)

The payoff would come when the author plots a tale in which one life-system goes over the ridge and meets another. The contact would combine the "otherness" of interplanetary travel with the grounded immediacy of planetary romance.

2024 April 29th:

EARTH AFTER MILLENNIA OF GALACTIC SPREAD

Emphyrio is one of Jack Vance's novels with an interstellar setting. Towards the end of the story the hero visits Earth, wishing to consult the Historical Institute about a mystery that has long haunted his mind. Vance's depiction of Earth a few tens of thousands of years in our future - see chapter 19 - is a splendid evocation of a culturally old yet lively world (a world, moreover, in which someone from our own era could still live - see The surprisingly human Vancian future).

For a month Ghyl roamed Earth, exploring the cloud-towers of America, the equally marvellous submarine cities of the Great Barrier Reef, the vast wilderness parks over which air-cars were not permitted to fly. He visited the restored dawn-cities of Athens, Babylon, Memphis, medieval Bruges, Venice, Regensburg. Everywhere, often light but sometimes so heavy as to be oppressive, lay the weight of history. Each trifling area of soil exhaled a plasm: the recollection of a million tragedies, a million triumphs; of births and deaths; kisses exchanged; blood spilled; the char of fire and energy; songs, glees, incantations, war-chants, frenzies. The soil reeked of events; history lay in strata, in crusts; in eras, continuities, discontinuities. At night ghosts were common, so Ghyl was told: in the precincts of old palaces, in the mountains of the Caucasus, on the heaths and moors of the north.

Ghyl began to believe that Earth-folk were preoccupied with the past, a theory reinforced by the numerous historical pageants, the survival of anachronistic traditions, the existence of the Historical Institute, which recorded, digested, cross-filed, and analyzed every shred of fact pertinent to human origin and development... The Historical Institute! Presently he would visit the Institute's headquarters in London...

It's just occurred to me that in some sense Vance's Earth bears quite a lot of resemblance, mood-wise, to Old Mars!

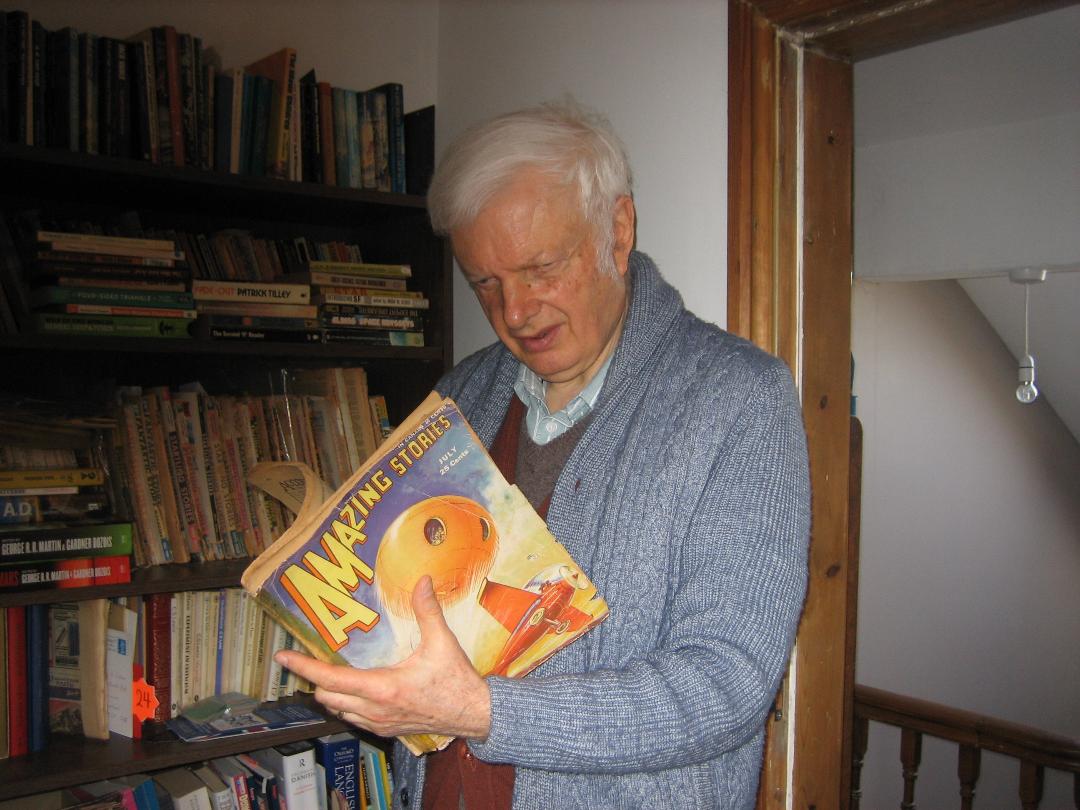

leafing through Amazing Stories, July 1931 (the cover announces "Spacehounds of IPC")

leafing through Amazing Stories, July 1931 (the cover announces "Spacehounds of IPC")2024 April 7th:

BE NOT OVER-PROTECTIVE OF OLD PULPS

Browsing in my collection of Golden Age sf magazines I asked myself, "Why don't I do this more often?"

Partly it's that by and large the best stories are to be found collected in books. But that doesn't altogether diminish the attraction of the magazines, which are full of character and nostalgic atmosphere.

No, a good deal of the motivation for NOT leafing through the pulps is that every time I do so some of their substance flakes off! In that respect they're a diminishing asset. Their mortality becomes all too visibly obvious whenever one of them is lifted from the shelf.

However, here comes philosophy to the rescue. A more positive, live-for-the-moment attitude to enable me to enjoy the collection without worrying too much about preserving it. Instead of over-protecting stuff that is bound to vanish at some later point in the time-line whatever I do, why not be content with an awareness of the eternal reality of the time-line itself? After all, anything that has ever been is anchored permanently in its indestructible temporal niche.

Hardly an original thought, this. But it sure is particularly apt for sf pulp collections!

2024 April 5th:

A NINETEENTH-CENTURY QUARRY OF STORY-IDEAS

While engaged in putting another couple of entries on the History of Hopes page, and reading around them in the vast reference work The Extraterrestrial Life Debate 1750-1900 by Michael J Crowe, it occurred to me, more forcibly than ever before, how authors of present-day NOSS fiction could do very well to browse in that volume.

For example we find that John Herschel (son of William) in a treatise of 1833 has what seems to me would have been a brilliant idea for 1930s style Amazing Stories fiction. He talks of

...absolute aridity below the vertical sun, constant accretion of hoar frost in the opposite region, and, perhaps, a narrow zone of running water at the borders of the enlightened hemisphere. It is possible, then, that evaporation on the one hand, and condensation on the other, may to a certain extend preserve an equilibrium of temperature, and mitigate the extreme severity of both climates.

Now think of this in connection with the slow rotation of the Moon: the narrow opposite zones of frost and running water would be always on the move, always impossible to spot from Earth due to their positions on the terminator, but waiting as a surprise for the first lunar explorers...

Ideal for an early gosh-wow Hamilton story.

2024 March 22nd:

URANIAN POLITICS AND A HEATING ENGINEER'S CALLIGRAPHY

To illustrate the inexaustible richness of life's interconnectedness, exemplified by the limitless options of associational thinking, here is a true little anecdote.

A few days ago our gas-boiler went on the blink and we had to get an engineer to fix it. (Fortunately it's under a seven-year warranty.) After he'd fixed it he informed us it had been a problem with the "diverter pipe". And that's what he wrote on his report; at least, I suppose it was - but his handwriting, which makes an "r" look like an "n" and an "e" look like an "o", suggests "dionton" rather than "diverter".

Now this got me thinking up a name, and an idea to go with it, amounting to a useful little brick in my edifice of world-building.

In recent weeks I've been trying to work out, in greater detail than before, the contents of the final volume of Uranian Throne - specifically the climacteric chapters in Olhoav, which deal with the tyranny of Dempelath. One aspect of this misrule could be the imposition of new vocabulary on the long-suffering subject population. Renaming things in a tendentious way; Newspeak, and so forth. One target whom the regime could aim at is the the city-brain, Dynoom.

Dynoom, an ancient and humane AI, is a natural focus of opposition to Dempelath. The latter could not risk destroying this Brain, which is needed for city maintenance, but instead could try to enforce an uncomplimentary renaming. What could be the new and insulting name? Well, why not adapt "dionton"?! Change the vowels to be more suggestive of lowering, of underneath-ness, and we get "Dyuntun", a derivation, perhaps, of a Uranian term for "excrement" - who knows? And the regime would proceed to "cancel" anyone who insists on still calling the Brain by nen's true name, Dynoom.

I ought to thank the engineer really...

2024 March 18th:

THE SURPRISINGLY HUMAN VANCIAN FUTURE

Currently re-reading the Cadwal Chronicles by Jack Vance, especially volume 2, much of which is set on Earth, I am reminded of the distinctively "normal" future portrayed in this and in his other Gaean Reach novels.

They are set tens of thousands of years from now, in an epoch in which human settlement spans "a perceptible fraction of the galaxy", and yet though there are innumerable cultures on countless worlds, some of them weird in their ideologies and customs, none of them have that techno-weirdness which advanced far-future societies tend to have in sf.

It's as though we might have a third option, one that is neither going computer-crazy or genetically engineered crazy, nor stagnant and neo-medieval; neither dystopic nor savage: rather we might, instead, relax into a chaotic, colourful sprawl of recognizably human civilizations.

Even Old Earth itself is neither built-over nor a wilderness; it is very, very old but as ramshackle as ever, full of cultural nooks and crannies. The heroine, Wayness Tamm, visits old Kiev, and we're told it has been rebuilt long since in the same style as before; the rebuilt version now already aged.

Vance can make the scenario believable by his provision of relatively cheap interstellar flight and an abundance of habitable destinations. I reckon it would really work that way: given such a state of affairs there'd be a sort of Sprawl Effect causing a relaxation of social tensions and of historical pressures, so that techno wizardry would no longer be in such demand, nor would "progress" (i.e. a regime of ever-weirder arrangements) keep its hold. An old city might be rebuilt without the occasion serving as an excuse for modernisers to obliterate the place's character.

In which case, we really might be in for a long afternoon of human humanity. Just one problem: I don't see cheap interstellar flight ever being achieved...

[See also the second Gazetteer entry for London]

2024 February 7th:

SYNCHRONICITIES OF 1967

The growth of legends is an unplanned evolution, springing from the confluence and overlap of ideas, and it's fascinating to catch it in its early stages. One of the reasons I am a post-Columbian American history buff is that one can watch a documented rise of a culture's character from the outset, its mystery materialising in the clear light of day (pre-Columbian has a different allure altogether, more like early British history, its origins fading back into the mists of time).

The growth of literary Old Solar System worlds is another instance of traditions' growths via creation-by-overlaps. I've gone on about this sort of thing often enough, in the pages of this site and in the introductions to the Vintage Worlds anthologies.

Just now I'd like to mention a third instance: something created by the conjunction of fictional dates.

It has become obvious, as I come across more and more references to add to the Fictional Dates page, that for some reason certain year-numbers have acquired (shall we say) a more dramatic ring-tone than others. Not the obvious "round-number" ones either: just have a look at the page, scroll to the year 1967 and you'll see what I mean.

No fewer than four authors are cited with their own fictional "take" on 1967. Three of them - Burroughs, Cooper and Cummings - refer to it as a notable war year. Clarke has it as a milestone in space exploration.

As one might expect, such coincidence becomes rarer the further ahead one looks along the infinite timeline. It becomes more a matter of spotting the clumps or clusters that appear in specific decades rather than single years. For instance you could maybe have a look at the 2050s and the 2170s. And please let me know of any discoveries of your own, that would do well on the timeline!

Come to think of it, the 2020s are pretty rich...

2024 January 29th:

THE DISNEY JOHN CARTER

My

wife Mary bought me the DVD for my 70th birthday, which was on 20th

January, and we got round to settling down to watch it last Saturday,

the 28th. I have to say...

Stid: Stop before you opine: I'm more interested to know how she got on with it.

Zendexor: She quit part way through. Apologetically, she excused herself on the ground that she found it "rather weird". I dare say she's not used to Martians.

Stid: Whereas you must have been in your element...

Zendexor: Well, no: actually I found it weird too, but for a different reason: namely, that I could only comprehend about a tenth of the dialogue. Why actors slur their lines like that, I cannot imagine. I don't suppose they're drunk, so what is it?

Stid: Perhaps what it is, is that you're exaggerating.

Zendexor:

If I am it's only because I ought also to allow for how the sound track

drowns out some of the words. But the slurring is the main problem. It's certainly not that I am incapable of

understanding an American drawl.

Admittedly, the best English - in fact, quasi-comphrehensible - is achieved by the Therns, who, being

villains, naturally sound more British than anyone else in the movie. Yet never have I had had any trouble

with understanding (for example) Humphrey Bogart, Gary Cooper or John Wayne. But this guy playing

John Carter... most of his utterances might as well

have been in Etruscan as far as I'm concerned.

Stid: I know what it is, Zendexor: you're going deaf.

Zendexor: Really? I had the same problem two decades ago with Gladiator,

in which I couldn't decipher Russel Crowe's mumblings; and I certainly

wasn't "deaf" then.

Stid: All right, then, that's enough of the bad news. Any good news?

Zendexor:

Yes: it was fun to watch in order to see what Disney made of Barsoomian

architecture and decor. The flyers looked good too, though they were

more suitable for Bradbury's ornate Mars than for the functional navies

of ERB's red men. Another plus is that Dejah Thoris was more impressive

than she is in the books! What else.... hmm, the banths. To me they

looked more like the great white apes ought to look, than the Barsoomian

lions they're meant to be; but anyhow, good Barsoomian critters of

whatever species. I rather liked Woola too. Even

John Carter himself, though too

scruffy and moody to be my idea of the Virginia

gentleman in Burroughs' books, seemed likeable enough.

Stid: Is that the end of your struggle to find something positive to say?

Zendexor:

No, there's more: I'm going to end with a BIG plus. Something Disney

managed which Burroughs left undone. I refer to the whole mysterious

business of how Carter travelled between the worlds. Burroughs simply

copped out, though he got away with it (and no one else would have!).

The film does better; in fact, does it beautifully. Mystery remains, but (if I may put it this way) we're given something for the imagination to get its teeth into.

Stid: Are you ever going to see it again, do you think?

Zendexor: Yes - willingly - provided that I can see it with subtitles!

2024 January 27th:

"STRETCHED" HARD SCIENCE

Most of the time, I suppose, the idea we OSS fans have about the science in science fiction goes something like this:

Whereas in our Old Solar System sub-genre of sf the science is merely an underpinning mood, the science in "hard" sf is a more disciplined and stricter restraint on what is permissible... Most of the time, anyway. But -

It sometimes appears that, running between this pair of attitudes, there can be a kind of cross-link, whereby the imagination's desires spill over to play a strong part even in the hard stuff.

Let's consider a couple of episodes in the works of Arthur C Clarke.

The first is from The Sands of Mars, chapter 13. By this stage in the novel a fortunate accident has resulted in the discovery of a species of Martian fauna, contradicting the previous belief that only flora existed on the Red Planet. One of the Martian creatures, dubbed Squeak, has developed an affection for the story's human protagonist and has accompanied the expedition back to base:

The scientists had prepared quite a reception for Squeak, the zoologists in particular being busily at work explaining away their early explanations for the absence of animal life on Mars.

I'm especially fond of that sentence. It's a nice touch of gentle Clarkeian irony and makes it seem that he considers scientific explanations to be mere rubber-stamp authorizations of whatever fait accompli Nature presents us with.

One may go further - beyond what Clarke himself would have allowed - and views explanations not only as mere authorizations but as mere humble excuses, necessary window-dressing for the intellect, similar to the perfunctory nods accorded to science in OSS "soft" sf.

We

thus arrive at the view that causation itself is less important than

results. Wonders are what existence demands, and must be provided.

Teleology rules!

The other excerpt is from Childhood's End, chapter 18, in which a child has dreams which are visions of reality from far worlds.

It was a world that could never know the meaning of night or day, of years or seasons. Six coloured suns shared its sky, so that there came only a change of light, never darkness. Through the clash and tug of conflicting gravitational fields, the planet travelled along the loops and curves of its inconceivably complex orbit, never retracing the same path. Every moment was unique: the configuration which the six suns now held in the heavens would not repeat itself this side of eternity.

And even here there was life. Though the planet might be scorched by the central fires in one age, and frozen in the outer reaches in another, it was yet the home of intelligence. The great, many-faceted crystals stood grouped in intricate geometrical patterns, motionless in the eras of cold, growing slowly along the veins of mineral when the world was warm again. No matter if it took a thousand years for them to complete a thought. The universe was still young, and Time stretched endlessly before them -

I discussed non-breathing life in my previous Diary entry, but here the theme is presented not by the lovably lax Edmond Hamilton but by the formidably proper Clarke!

Well, he might have said, why not? Who's to say mineral life of that sort isn't possible, given the vastness of Time and Space and the surprises Nature can have in store? Why should hard-sf not allow for these intelligent crystals?

Yet here's a

comment I can't resist making: the thinking minerals are portrayed as

being way outside our Galaxy, and I do wonder whether Clarke would have

stretched his science so far, if the distance hadn't been far as well.

Can you imagine him writing about similar crystals on, say, the moons of

Uranus or at the poles of Mercury? I must say I can't.

It's

like a hard-science fictioneer, when indulging in a bit of naughtiness,

must do so well out of range of the OSS... an evasion which, when you

think about it, isn't so very scientific after all.

2024 January 23rd:

AT HOME IN VACUUM: THE SPACE-DOGS OF CERES

The Three Planeteers (Startling Stories, January 1940), which I learned about from Guess The World contributor Lone Wolf (see Attacked in a fungus forest on Saturn), is a tale I'm reading bit by bit, rather than devouring at one go. This goes to prove that I wouldn't class it among Edmond Hamilton's unputdownable yarns.

However, it has turned out to be an unusually rich source of material. I've quarried the text for the Guess The World, CLUFFs and Fictional Dates

pages and I have good reason to hope that the plot will develop into

providing yet more for GTW. Quite good going for a single novella.

And its latest yield - GTW scene number 362 - has given me something to reflect upon here. The "space-dogs" (see Lungless creatures evolved on airless Ceres) are great examples of one way in which the OSS can make the smaller worlds of the System more plot-friendly.

The

other way is more lavish, more defiantly unrealistic: the provision of

soil, water and a breathable atmosphere to tiny asteroids and moons

which in actual fact can only be barren lumps. This insouciant attitude

to scene-setting has given us many a delightful read, such as Leigh Brackett's The Lake of the Gone-Forever, John Wyndham's Exiles on Asperus, Ray Bradbury's Perchance to Dream and Eric Frank Russell's The Saga of Pelican West.

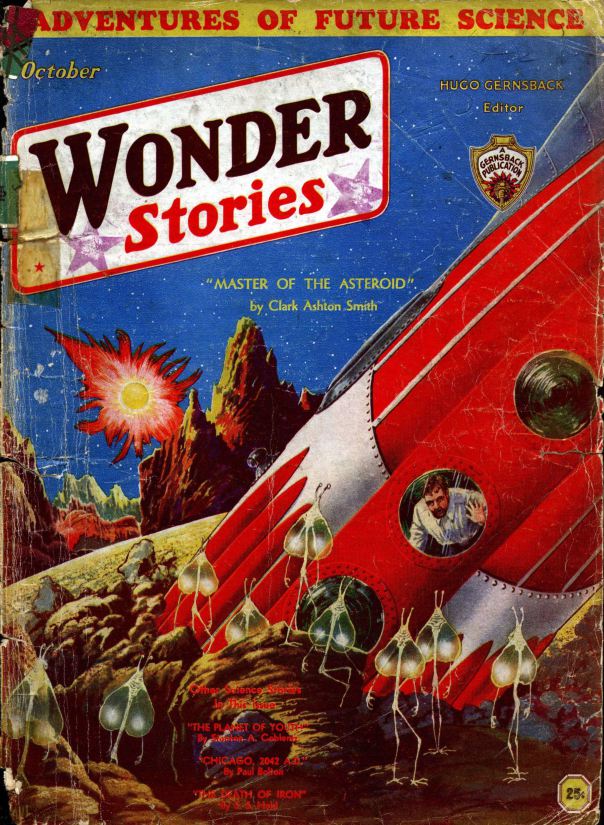

(Or in a variant version the atmosphere might be too thin to be breathable by humans but yet substantial enough to support some life, which is what I seem to remember is the situation in Clark Ashton Smith's Master of the Asteroid.)

But the "lungless space-dogs" idea gives us a powerful alternative, an extra shove at the frontier of opportunity. Airless evolution can people the coldest, darkest worlds, where even the stoutest OSS fan might baulk at the suspension of disbelief required to give them air and water and respiratory life.

Another advantage is that it can spread native life to that world which we all think of as airless in both fact and fiction: namely, our own Moon. (See Keyhole by Murray Leinster - discussed in Lunar surface creatures.)

One

last point: is the idea of airless evolution all that unrealistic?

Life depends on - is a sort of re-arrangement of - energy, and energy in

one form or another pervades the universe. Think of cosmic rays; and

then think of all the other things we haven't thought of and don't know

about... and then you may conclude that the space-dogs aren't so

far-fetched after all.

2024 January 17th:

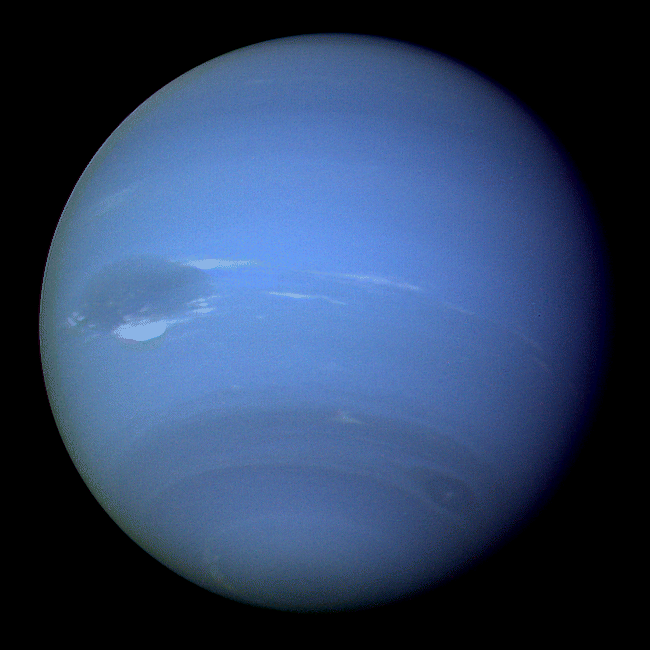

NEPTUNE SCORES A POINT FOR LIFE

This little entry is a continuation of one I wrote almost seven years ago, focused upon Saturn, under the title IT JUST MIGHT BE.

In it I referred to the conversation in Footfall on the subject of whether an alien spaceship which had come from the direction of Saturn could possibly originate there. The consensus was "no" to the possibility of a Saturnian civilization, but not an absolutely sure "no". What fascinated me about that passage in the novel, was that although we may be used to thinking in certain boundaries, when something unexpected actually happens we are faced with the fact that we can't regard those constraints as absolute.

"Saturn," Aylesworth said. "Saturnians?"

"I doubt it," Ed Gillespie said. "Saturn just doesn't get enough sunlight energy for a complex organism to evolve there. Much less a civilization."

"Sure about that?" the President asked.

"No, sir."

I felt like cheering when I read that "No, sir". Though in the novel itself the doubt is swiftly forgotten, the point as far as I'm concerned is memorable and vital: no matter how strongly a hard-science buff may protest that at Saturn's distance from the Sun a planet can't have the energy budget to afford a biosphere, you really cannot be sure: and lo and behold, a few years after Footfall was written we were all treated to a real-life surprise on how much energy a yet further world can possess.

I well remember the news of Voyager's Neptune encounter (I was at an Open University summer school at the time): I remember the official amazement at the pictures of Neptune's dramatically turbulent atmosphere. Whereas Uranus three years earlier had shown as bland, Neptune - almost twice as far - was full of vim!

I'd be willing to bet that the basic energy for life is available anywhere in the Solar System. Perhaps the further out you go, the slower life is, but that's all right.

Of course, scientific realism isn't the point anyway, as far as most of the literature discussed on this site is concerned. The essential mood-music or drama-prop which Science provides is all we OSS fans need.

Still, it's nice for us when Nature seems to stretch a point in our direction...

2024 January 11th:

Note addendum to the entry on January 5th.

fumbling for Amazonis Planitia

fumbling for Amazonis Planitia5th January 2024: