Valeddom

1: before the crash

You probably won’t believe me. But if you’re one of the few who do, then you will want to know how I survived, for there’s nothing, that I know of, to stop the adventure happening to you, or to anyone.

Those of us who have come back, salvaging their old selves, have a duty to report. That’s why I am writing this.

But don’t expect me to give you all the answers. Often, I wasn’t sure why I made the moves I did. No doubt I missed some better paths, which you may find. But at least I did get back in one piece!

My advice to you, if you find yourself caught up in what’s waiting for you out there, is not to work things out, nor to rely on rules, but to listen to certain voices deep within you – voices telling you that you already know more than you think.

This is dangerous talk. But it’s dangerous to ignore it, too.

Now I’m going to take my own advice. An inner voice, a hunch, tells me to start, not with the shock of my arrival on Valeddom, but with Mr Bryce’s geography lesson the afternoon before.

That lesson, it’s fair to say, was the best ever experienced by Form 9c of Dallingdon School. And though I can’t prove it, I suspect that it’s one of the reasons why I am alive now.

*****

We were rather a challenge to our teacher that Thursday afternoon. For one thing, it’s not very easy to concentrate on any kind of work while warm sunlight splashes in through the window onto your desk, tempting you to look out over green fields under a blue sky (our school is on the edge of town), especially when there’s only forty or so minutes left before the last bell.

But also, on this occasion, we had a special tomorrow to look forward to. A school trip, by coach, to the science museum in Manchester; a moderately exciting prospect, which had the effect of making Thursday afternoon seem like Friday afternoon. I felt decidedly lazy. Yet compared to some of the layabouts in class I was a mere amateur in work-avoidance. If I had been in Mr Bryce’s shoes I think I would have given up trying to teach a proper lesson, and just told us to get on with our revision reading. Mr Bryce, who as far as I can remember has never taught a boring lesson, did not take this easy way out.

He was a chunky, deep-chested man with a dominating voice, who controlled his classes with sheer force of personality and hardly ever needed to punish anyone. That afternoon, he was determined to coax us into a frame of mind for getting the most out of next day’s Science Museum trip. Cunningly, by the way he blended ideas in his talk, he mixed various big themes together: scientists, explorers, history.... and us.

“Tomorrow,” he announced, “you are going to be pioneers.”

This caught our attention. Of course, we all thought there must be a catch. He couldn’t mean it literally....

“Pioneers,” he continued, “are people on an advancing frontier. Isn’t that so? Well, here we are on an advancing time frontier! Trolling along at sixty minutes an hour! Our individual histories pushing ahead like new lines wiggling across blank paper! In other words, merely by living we are making history every day, and anyone who isn’t interested in history is dead.”

Mr Bryce paused for breath.

“You’re dead, Butterworth,” drawled Fred Jackson, breaking the spell.

Butterworth being the class delinquent, we all laughed. Yet in making that smart crack, Jackson made himself a target.

Confrontations between Bryce and Jackson were always worth watching. Jackson, like some kind of licensed jester, always sensed just how far he could go. And I reckon that Mr Bryce, sensing the value of their double-act, encouraged it by the way he picked on Jacko – a compliment to the lad’s maturity.

As a matter of fact, Fred Jackson had a good reason for being more mature than the rest of us: he was a year older, having had to repeat our year instead of going up to the next one. Not that he was especially thick; just academically bone idle. He was the son of a wealthy couple from Louisiana who were over here on some scientific posting, and I suppose he knew he would never have to do any serious work.

Big, husky and handsome, he was the clean-cut, confident type who would look good in an ad for shirts. Naturally popular with the girls, and respected by the lads because of his sporting prowess, he was not (I believe) close friends with anybody. Perhaps it was lucky for him that he had had to repeat the year. It humbled him just enough, to place him within reach of our tolerance.

Now, as we sat back to watch the latest bout between him and our favourite teacher, we were prepared to cheer either side.

“And what about you, Jackson; in contrast to Butterworth are you alive to history?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Really? You can liven up the field, like your namesake, eh?”

“Is this an in-joke, sir?” He was playing along, knocking the ball back to Bryce.

“I was referring to your countryman, the famous American historian of the Western frontier – Frederick Jackson Turner. Never heard of him?” Bryce sighed. “If only you people would read more,” he tut-tutted at us all, “instead of sitting glued to the idiot-box for hours every night, you’d get better grades and enlarge your lives. Ah, well.” Bryce sighed again. “The trouble is, we’re living in the wrong age. If I were saying all this a couple of lifetimes ago, your eyes would light up at the word frontier; but the sad fact is, there don’t seem to be any, not any more.”

It was startling, how “on target” this was. Our teacher had suddenly connected with us – he had hit upon a regret which is usually ignored because so little can be done about it. Yes, we were frustrated explorers!

So the class awoke, as if by magic, to a level of passionate discussion that only happens once in a blue moon.

Jackson grumbled, “That’s just it, sir; where is there left to go?”

Dave Harper objected, “It’s not that bad. After all there are still some areas of Earth unexplored.”

“Like the Amazon rainforest,” suggested Janice Dodd.

“What’s left of it,” gloomed Jackson. “But anyhow that’s not real frontier stuff; that’s just filling in gaps. Or stunts, like that guy Fiennes.”

Mr Bryce prodded us further.

“I’m not belittling Fiennes and his like,” he remarked, “but Jacko has a point. Sure, we can add to our knowledge, and adventures in out-of-the-way parts of the Earth are real adventures, adventures that you can get killed in, but still, it’s not exactly Columbus is it? The Earth is all pretty well mapped by now. So what next?”

“There’s the oceans,” said Janice.

“You mean, real deep?” Jackson asked. “Who’d want to settle there? Crushing pressures; darkness…..”

We batted it about some more and reached a consensus that the oceans should be left to the fish, the squids and the whales.

“Of course,” added Bryce casually, “there is another direction,” and he pointed straight up.

*****

He got a mixed response. A few of us, myself included, made noises of agreement. The majority seemed less keen.

“Come on then,” Bryce said, “let’s hear the objections to space travel. It’s our last remaining option, unless you count caving, or tunnelling like moles.”

The objections came thick and fast. Disappointment, it seemed, had accumulated around this subject. Space travel was a wash-out because (1) it was too expensive; (2) the available destinations weren’t habitable; (3) the Solar System was already being surveyed by automatic probes and so the thrill of discovery was experienced by the ground crews at Mission Control instead of by real explorers out there.

Reluctantly, I had to agree. After all, how much adventure would have been left for Columbus if the Queen of Spain had already sent a robot probe across the Atlantic to send back images of America? He might have looked at the images and not bothered to go – especially as it wasn’t what he was looking for anyway….

And so Mr Bryce got us to think and argue about how too much prior knowledge can discourage the impulse to explore.

“It would have been so good,” he mused, “if a cheap, reliable spaceship had suddenly been invented back in the 1950s.”

“Why the Fifties, sir?”

“Because the Solar System was then still largely unknown – all the data we had were from fuzzy little pictures taken by ground-based telescopes, showing hardly any detail. So we, not the probes, would have streamed out and made all the discoveries.”

“Made them the hard way,” commented Jackson.

“Yes, well,” admitted Bryce, quite ready to argue the other side, “certainly a lot of explorers would have got themselves killed. E.g. they’d have discovered Jupiter’s radiation belts the hard way….”

Annette Sallis, a serious girl who got top marks in everything except imagination, said in her no-nonsense manner, “So where’s the advantage? I mean, what does it matter? Whether you explore in person or by remote control machine – if the Solar System contains no liveable place except Earth, don’t you get just the same useless result either way? Might as well not bother.”

Mr Bryce didn’t allow this dampening tone to spoil his show. He would have made an excellent TV chat-host, the way he made as much use of negative as of positive feedback. Now he turned to Aldridge, one of the dimmest yobs in class, and asked him what he thought: “Annette has brought the debate to a seeming dead end. How would you advise we get out of this, Gary?”

Aldridge, in his usual gormless voice, said, “We could go ’ome, sir.”

Some hollow laughter came from like-minded yobs who approved of this contribution, but Mr Bryce kept his smooth straight face.

“How about you, Justine?” he asked, turning to the poshest girl in class. Beautiful technique: he was keeping the show alive by setting up an entertaining contrast between one speaker and the next. Merely to name the regal Justine Lazenby in the same breath with Gary Aldridge is an excellent joke in itself. “Tell us how you would assess Gary’s judgement, that the debate has reached the point where we would do best just to go home?”

She produced one of her cool put-downs, completely effective yet not in the least bit nasty. She simply said, “He is entitled to his opinion.” It was the way she said it, which silenced the yobs. And then, in a helpful spirit, she added:

“I suppose, even if we can’t live out there, the Solar System may contain some useful resources....”

“That may well be true,” said Bryce. “So, perhaps we should just concentrate on mining our neighbouring worlds? Bit of a come-down for old-style science fiction fans, who hoped to see the day when we could actually colonise.... but still, something is better than nothing, eh?”

This is where I come into the story – though I almost didn’t.

It cost me an effort to speak about anything to do with outer space. Several months before (amazing how long a mocking phrase can hurt), just after a science teacher had said “And now for a bit of astronomy”, there had been a sneer from Pullen:

“Especially for Dent.”

Implying: “Astronomy couldn’t be of interest to any normal person, only to a spazz like Hugh Dent.”

You know what it’s like at age 13; you shouldn’t feel that crazy prickle of doubt and shame, but you easily do, if the Pullen faction – or whatever the equivalent may be in your class – is sufficiently loud, strong, numerous and determined to rubbish everything you value, so that you bitterly regret that you ever revealed your enthusiasm. And so I took it hard; ridiculously hard.

But today I discovered I was no longer hammered by that “Especially for Dent” memory.

In fact I was even beginning to feel grateful to Pullen and Co: grateful for the experience in psychological warfare. It had toned me up to figure out how to voice my idea without being jeered at by the twerp community:

Keep them guessing. And the way to do it is not to begin at the beginning. Instead, jump right into the middle. By the time they learn what you’re talking about, it’s too late to jeer.

So, casually, I said:

“Perhaps the Mercurians have learned to fool our radar.”

Silence.

*****

“What was that, Hugh?” asked Bryce, amazed.

“The radar results back in 1965,” I said. “Maybe they were a blind.”

The rest of the class hadn’t a clue. Why should they? None of them shared my hobby. That didn’t matter; the important thing was that Bryce knew.

“Ah,” he said, blinking from the shock I must have given him; then a smile spread over his face. “You mean that rather sad investigation, yes, back in 1965 I believe, that showed the planet must be rotating?” He was looking at me intently now.

I nodded, “And so gave us the bad news that there couldn’t be any Twilight Belt after all.”

Faces around me looked blanker than ever. Twilight Belt?

Bryce explained:

“Dent is referring to one of the most disappointing discoveries of modern science. People used to think Mercury rotated on its axis just once every Mercurian year, so that the planet’s day was the same length as its year, and therefore one hemisphere was always facing the Sun and the other always facing away into the night. The little world would therefore have had a perpetual day and a perpetual night side. And the exciting idea was, that between those two extremes of light and dark, of heat and cold, there would have been a belt in which conditions might have been possible for life. But then some meddlesome scientists in 1965 spoilt it all by disproving the synchronous rotation idea, so – no more Twilight Belt. Unless….” He glanced at me again, with a twinkle in his eye. “As Dent suggests, suppose the 1965 result was bogus; suppose the Mercurians were fooling our radar! Eh, Hugh?”

“Yes sir,” I said. “So, actually, the Belt might be real!”

(And when I said the word “actually”, I heard a murmur or two from somewhere at the back of the class; “eck-choo-elly….” “eck-choo-elly….” My blood ran all the colder, as the mockery was so expertly controlled, without audible snigger. The bad old days were back; but only for a moment.)

“Beautiful!” said Bryce. “After all, the people of a much smaller planet might well wish to escape our attention! It’s a cute idea – I like it – and we could enlarge on it. For instance, maybe the canals of Mars are real, too! The Martians, you see, have covered them over to conceal them from our nosey-Parker space-probes….”

He went on in this vein for the rest of the lesson, light-heartedly inventing reasons why this or that discovery might not be real, and older ideas might be true instead. You can reach any conclusion you like with that line of argument, so it can never prove anything, but it gets you thinking and imagining, and besides, he managed by this dodge to slip quite a bit of the history of science into our heads, so niftily that even the twerps in our class seemed spellbound. When the bell went, it was like the sudden end of a dream. Magic! A lesson like that.... you know you’ll remember it all your life.

*****

My dad is always coming up with business ideas. Enough of them turn out profitable to enable us to afford a comfortable home in Westmorland. This evening at supper he was enthusiastically going on about a notion he had of using potato starch as an organic substitute for some chemical poison used in pest-control. The starch could be sprayed on whitefly pupae so that the pupae would stiffen and the insects be prevented from hatching – at any rate that’s how I understood it.

I wish I had said more to congratulate him on his progress, but after the meal I was keen to go to my room. I just wish I had not been in such a hurry, and that I had given him more time and attention, since he was so excited about how his idea was coming on, and I knew, moreover, that it wasn’t just the money he expected to make – his face glowed lovably at the prospect that he might help reduce people’s reliance on poisonous pesticides. I, however, made for the door as soon as the meal was over.

“Are you hurrying off, dear?” said my mum, placidly.

“I need to look something up to do with my geography lesson. Mr Bryce is always going on at us to read more….”

“And just for once,” chuckled my dad, “you’re going to do what he says.”

“I read plenty,” I said. And it was on that indignant note that I left the supper-table.

I am the child of the second marriages of both my parents. I have adult half-brothers and sisters whom I hardly ever see. I get on very well with my mum and dad, and I’m not sure whether this is in spite of, or because of, the fact that they are in their fifties and in some ways more like grandparents than parents.

My dad is quite a successful businessman with fingers in various pies, but he seems old-fashioned in his methods of organization. Everyone else I knew had a personal computer years before we finally got one. Our house is full of old books and he seems to get ideas more from reading and thinking than from Internet-based research. His latest idea, the potato-starch pesticide, is an example of this.

To some extent my upbringing has been influenced by this tendency to value old, out-dated sources of knowledge. One birthday present in particular changed the course of my life:

When I was six years old my parents gave me a strange gift which actually was a mere afterthought, not meant to be the main present at all. Dad had found it while clearing out some of his old stuff. It was a pictorial encyclopaedia, still in quite good condition, which he had possessed as a child, and he guessed it might appeal to me.

He was right. To such an extent that I have forgotten all the other birthday gifts I received as a small child, and remember only that one. Especially pages 70 and 71. They hit me with such force, that from the moment I saw them the word “planet” became magical for me.

I recommend to you the power of old illustrations. New ones may be slicker but something is lost in the slickness. You may doubt this, or at any rate you may say that the old pictures are only powerful if one looks at them with the eyes of a child. My answer to that is, that the eyes of a child are on to something big.

The double-page spread showed nine small landscapes, artists’ impressions of scenes on Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, Neptune and Pluto. To my six-year-old self, they contained wonders and marvels which had nothing to do with the scientific intentions of the book. As an example of how little I understood, let me confess that I thought the Saturn picture had a huge rainbow in it; I didn’t understand that it was the artist’s attempt to show Saturn’s ring as it might appear from the planet’s surface. (Of course, we now know Saturn has no surface; it’s mostly a ball of gas.)

The odd one out among the nine pictures was the third one; for me, the only boring one. It showed a scene on Earth. Just a pleasant country landscape, with fields and hedgerows, the sort of thing I saw around me every day, and which therefore evoked none of the awe and fascination which the others did.

Perhaps the scene which made the greatest impression on me was the first of the nine – that of Mercury.

If you saw it, you’d almost certainly decide there wasn’t much to it. Just a barren, rocky plain, a starlit sky, and a few crags. But of course, what counts is not what you see but how much you see through – and you either know what I mean by that, or you don’t.

In the years that followed that memorable sixth birthday I came across three old classic science-fiction stories set on Mercury: Clark Ashton Smith’s “The Immortals of Mercury”, Leigh Brackett’s “Shannach – The Last”, and Alan E Nourse’ “Brightside Crossing”.

They all depict the “traditional” Mercury with permanent day and night sides and a Twilight Belt between. But apart from that they differ very widely. “Brightside Crossing” describes a world with no native life. In the other two tales, the Twilight Belt is inhabited, and in fact not only life but powerful superhuman intelligence is to be found there. In the Brackett story a silicon-based giant, the last of his species, lords it over a secret valley filled with human slaves. In the Smith story the Mercurian Immortals live underground.

If you ever read these three superb tales and compare them, you may start to notice an important and peculiar fact. Although they are so different from each other that you might logically conclude that they could just as well be set on different worlds, actually this isn’t so – actually it matters that they are all set on Mercury. In other words “Mercury” as an overarching theme is something greater than the huge differences between one story and another.

Whatever this thing was, that they all had in common, I developed a hunger for it, and kept a look-out for further Mercury stories. In vain. It’s not a common subject, to say the least. And never did I find a single entire novel set on that planet. Plenty of novels set on Mars and Venus, but none on Mercury.

I never wholeheartedly accepted the scientific disproof of the old-style Mercury. My imagination so much preferred the stories to the science, that you could almost say I had the attitude “if science doesn’t agree with this, then so much the worse for science!” It’s as though I couldn’t care less about what was true. Or it’s as though I actually believed what I jokingly said in that afternoon’s lesson, that the scientists had been fooled.

However, that evening, when I went upstairs to open the old encyclopaedia one more time, I was determined to say goodbye to my childish obsession. I would take a last look at the pictures for old time’s sake, to see if they preserved any of their old magic, and then I would get my head adjusted to reality. I had an ambition to get good grades in science. Maybe take it at university. Who knows, perhaps earn my living by it one day. Some people achieved this; why shouldn’t I? But I never would if I continued my fixation with out-of-date ideas. It was time to “get real”.

So I prepared to say my farewell to the old dreams. I opened the book to pages 70-71 and there they were. Bye-bye, beautiful scenes.

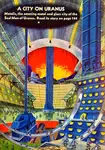

Mercury with its starlit cragginess (it must be the Night Side). Venus with murky peaks and cloud-cover. Earth which didn’t count. Mars with a hint of green vegetation and a cushiony dust-cloud billowing across a background hill. Jupiter with tiers of volcanic fires (it used to be believed that Jupiter had a surface and that this surface was hot). Saturn with its “rainbow” arching over misty mountains. Uranus with fan-like peaks and pink clouds, goodness knows why. Neptune with a strange horizontal bar of luminous green mist illuminating rock and water. Pluto (which counted as the ninth planet in those days; it hadn’t yet been demoted to “dwarf planet”) with a sugary-looking landscape which, I now understood, was supposed to represent extreme cold. There were some icicles in the picture, as though you’d really get dripping water on Pluto.

All wrong. All untrue.

Admittedly, some glow of the old enchantment was still there, or at least the memory of it was. But the trouble, in this kind of situation, is the scantiness of the supply. One always wants more of it, and there isn’t any more. Knowledge has changed, art has changed; and one’s own self has changed.

Well, the out-of-date wonder had played its part in my young life, and in this afternoon’s lesson I had successfully made a game of it. But tomorrow I was going to the Science Museum and this was as good a time as any to make the effort I was going to have to make, to get tuned into things as they actually were.

For my business now was to concentrate on getting good exam results and then go for a career, in the kind of science which no one could laugh at.

Goodbye, old friend, I thought as I closed the book.

*****

Next morning, I woke a quarter of an hour late. My alarm had failed to go off. I still got ready in time but then met further delay in the shape of our cat, Fuzz, who started following me to school; after trying unsuccessfully to shoo him back, I had to pick him up and carry him home. Having lost several minutes over that, I really had to run. And as I tore round a gravelly corner I slipped and fell painfully. After that I had to slow down.

What with one thing and another – the stress of being late, worrying that I might miss the coach, and all the big thoughts in my head from yesterday – I didn’t see Pullen and Aldridge until they were too close for me to take evasive action.

Pullen stepped across to block my way. Aldridge got the idea and joined him.

Bad luck for me that this was happening just short of the last street-corner. Beyond it, I would have been in sight of the school gates and of the parked coach that was waiting to take us all on the trip.

Pullen put out a hand and said, “Eck – choo – elly.”

I stood still and wondered all sorts of things in that moment: were he and Aldridge “bunking off”, were they trying to make me miss the coach too, and why had Nature or Evolution produced two such mistakes.

“Eck – choo – elly,” repeated Pullen, “the Twilight Belt might be real!”

“Cor!” said Aldridge.

I tried to get past them and they moved to block me. I thought it a sad pity that the jail which no doubt was waiting for the adult Aldridge could not receive him a few years in advance. As for Pullen – he would be more likely to frame someone else into a jail sentence than to get one himself.

“This is a problem,” I said aloud.

“You said it, eck-choo-elly!” brayed Pullen.

“No, really,” I said, looking puzzled; “I mean, Neanderthals are supposed to be extinct, so – ”

In the split second before Aldridge threw his first punch I cursed myself for a fool. The last thing I’d wanted was a fight, but since I hadn’t been able to resist repaying taunt for taunt, what else could I expect? And not only was I outnumbered two to one but I wasn’t committed enough, I couldn’t hate enough; it’s hard to hate creatures whom one regards as little more than vicious animals, and without hate, what force can drum up the urge to fight? Fear would be another motive, but I didn’t even have enough of that – until the first punch landed. Then I tried to move fast, to keep Aldridge between me and Pullen, but even reducing the odds in this way wasn’t going to get me anywhere, since Aldridge could beat me up without any help. And now fear loomed large, that I might miss the coach, and as more punches landed I became not only hurt but confused, stupidly unable to comprehend what was happening, just as though I had never heard of bullying before.

Then the whole picture changed. “Come on,” said an impatient, female, stop-being-so-silly-and-snap-out-of-it voice.

It was Annette Sallis, poking her head round the corner. Another, taller figure appeared at her side: Fred Jackson. Suddenly the atmosphere seemed full of common-sense. The sadist and the thug dwindled into two pitiful little boys. I lurched upright; Pullen and Aldridge likewise staggered, theatrically, to make the onlookers think that we’d just been mildly horsing around.

Running my fingers through my hair and smoothing down my clothes, I gladly obeyed Annette’s summons to “come on”.

I wasn’t too badly mussed up. The fight hadn’t really had time to get serious. I doubted that I was even visibly bruised, and anyway, nothing was going to stop me getting on that coach.

Rounding the corner into the Russet Lane school car-park I saw that there were actually two coaches. I might have guessed that one would not be enough; after all, the entire year were going on this trip. Each coach window revealed the dense population of noisy, excited youngsters who had already swarmed into both vehicles, the waving, the shoving, the tussles for seats; the way some of them darted about, I was suddenly prompted to imagine that I was gazing into an aquarium; one can, after all, talk about “schools” of fish. And at the moment I was the fish-out-of-water…. I stood wondering which coach to board when I heard the unlovely voice of Aldridge shout “Toofy!” and wave to someone in the rear coach. He and Pullen ran to that one; I therefore turned to head for the other. But a hand on my arm restrained me. “Wait,” said Annette.

She and Jackson had no formal authority, but were like unofficial prefects. They had built up this status amongst us, because they were not afraid to “tell tales” to the staff when necessary and yet at the same time they could not be considered “sneaks”; previous little crises had shown, in a manner which even a yob could sense, that they had a capacity beyond their years for judging when and how much to tell. Now they were doing their best to encourage some sort of order in the absence of proper supervision. Something had gone wrong – there were no teachers in sight. Jacko said to me, “The drivers shouldn’t have opened the doors. Bryce and Ferrar aren’t gonna like this.”

Even as he spoke, I spotted Mr Bryce and Mr Ferrar coming out through the school gates. Something had happened (I never found out what) to delay them. As they walked past us I heard them almost growling their annoyance at the rowdy mess. “Out, all of you!” boomed Bryce, tackling one coachful, while his colleague went to empty the other. Matters were set to rights: we were all lined up properly and counted, and an outdoor register was taken; then began a proper, orderly embarkation. While this was going on Bryce drew Annette and Jackson and me aside and said a few words of thanks for our “restraint” and “responsibility”. That meant that we were last in – and we went into the lead coach with Mr Bryce.

The best seats at the front had been taken, of course, but quite a few of my schoolmates seemed to want to gravitate to the opposite end, doubtless on the assumption that supervision would be more lax back there. Anyhow, the upshot was that there was a row of four seats about three quarters of the way up towards the front end which were still free. Annette and I found ourselves going forward together to this area. Each of us bagged a window seat; hers the left one, mine the right, so we each sat alone, with the gangway between us. Jackson meanwhile got into a conversation a few rows back and joined that group.

I un-slung my rucksack and placed it on the empty seat beside me. Annette had done the same with hers. As the coach revved up and got going, she seemed content to look out of her window and that suited me fine. To be perfectly honest, though I was grateful for her intervention in the bullying, I simply wasn’t up to trying to make conversation with her. Completely unimaginative, she would soon have driven me to seek inspiration from the printed notices on the walls of the coach, in case they contained any bright ideas about what to say.

Besides, I was content with my own company. A peaceful coach ride was just what I needed, to try my plans on for size. My ambitions for a scientific career were vague, but at least I was starting to think ahead; such practical thoughts were a new departure for me. This and the pleasure of the ride, coming so soon after the bullying, made me notice all kinds of things more vividly than usual – the trees and houses flowing past outside, the seating arrangements on the coach, the glints on Annette’s dark hair. I was thirteen and full of opportunity. Having accepted that the old wonder in the old book’s pages 70 to 71 was an irrelevant fading distraction, I looked forward all the more keenly to getting on with something real.

Mr Bryce was sitting two rows back from me, on the left. If I turned my head and peeked through the gap between the two seats which I and my rucksack occupied, I could just see him. He sat alone, at first. However, before many minutes had passed Justine Lazenby came swaying up the aisle and perched elegantly on the edge of the seat next to him.

She was asking him some question which I could not hear. Any other girl who made this style of approach to a teacher would have been teased unmercifully for “making up to Sir”, but where Justine was concerned, different standards applied. Her move was likely to be regarded more in the light of a queen making a state visit to one of her fellow monarchs.

The state visit over, Justine got up again and I naturally expected her to resume her former seat. But no, she was coming forward. Towards the front of the bus, towards me in fact – and, wonder of wonders, she lifted my rucksack out of the way and plonked herself down in the seat next to mine.

With a shivery double-take my poor brain took on board what had happened. This wasn’t just any old overwhelmingly beautiful girl, this was the super-self-possessed Justine Lazenby who from some unknown source drew the power and dignity that prevented even the most sniggering yobs, even amongst themselves, from taking any liberties with her, as far as I ever could tell. Unscathed she glided through school life, and no mud stuck on her. Not even envy. For with all her beauty and genuine superiority she was also, quite obviously, a good-hearted girl. She could have done a lot of harm if she hadn’t been.

“Hello, Hugh, may I sit here a bit?” she asked.

Feeling like a peasant being addressed by a kindly empress, I somehow retained enough common sense to gulp something that meant yes, of course you can sit here.

Justine and I had occasionally exchanged greetings before, and I wasn’t absolutely tongue-tied, but still, this was a heart-thumping situation to be in, with scatty thoughts bursting in my head like shell-fire over a World War One trench. And like the poor Tommies in the trenches must have feared being blown to bits when they “went over the top”, my great fear was of messing things up, of being pulped by feelings I could not control. Come on, Hugh, pull yourself together…. Oddly enough, I did so. Perhaps other recent thoughts helped. Down-to-earth wakefulness; decision to seek a practical career; this sort of realism may (for all I know) have helped me likewise to see the girl realistically, to break her spell. Grow up: don’t believe in magic any more. I said to myself: what we’ve got here is no more and no less than a tall slim attractive girl with long brown hair, full red lips, merry eyes. Nice, but nothing to get jellied over…. So for the first time ever, I made the effort to view Justine Lazenby as on the same level as the rest of the human race.

She had a briefcase with her (no mere rucksack for Justine) which she now hauled up to rest on her lap. She clicked it open.

“Doing your homework on the coach?” I managed to say.

She flashed me an impish smile.

“Just a bit of Geog. that I’m late with,” she murmured. “A pie chart is the main thing. Mr Bryce told me I had misunderstood the question and so I had to do it again…. Do you happen to have a compass on you?”

I dared a witticism. “No, but I can tell you that North’s over there,” and I pointed back over my shoulder.

“Oh ha ha, I shall rephrase my question, do you have a pair of compasses, please?”

“Sorry, nothing but a pen and notepad.” I was so relieved to hear myself giving rational answers, so relieved that I hadn’t made an outward fool of myself despite boiling and churning inside, so pleased at the longest successful run of conversation I had ever had with Justine, that it seemed as if the war – the war against my own nerves – was just about won. Really, why worry? It was all so simple: just keep calm, keep realistic and count your blessings. No need to rack your brains to think of ways of “making conversation”; something would come along to make it obvious what to say. If nothing else you could offer her a drink from your thermos flask.... hey, there’s another idea –

I suggested that Justine could still draw a circle even without the compasses, just by drawing round the base of my thermos flask, which was about the right diameter for a pie chart. My suggestion was graciously accepted. She took it and began to draw, carefully and slowly, and quite successfully despite the motion of the bus.

Mr Bryce, meanwhile, had got up and for some reason was coming forward, stooping and pulling himself along past us towards the front, evidently wanting to speak to the driver of the coach. As if his move had taken the lid off a pressure cooker, there was an immediate scuffle somewhere right at the back.

Bryce hadn’t yet noticed the misbehaviour; he was saying something to the driver about scheduled stops. I then heard a serious American voice from mid-coach calling to the scufflers to “be your age”, and another, louder voice jeered, “Nyerr, shut your face, Jackson – look who’s talking – look who wasn’t good enough to go up!”

That was the standard way of getting at Jacko: to taunt him for having had to repeat the year. Certainly his attempts to exercise leadership didn’t always work. On the other hand, he wasn’t a bit fazed.

He retorted, even more loudly, “Why don’t you get on steroids, Shorty, so you can grow a bit?”

Everyone heard this, and there was a general laugh which even the returning Mr Bryce joined in. “Shorty” was Geoff Croyland, who tended to over-compensate for his small stature.

I made eye contact with Justine and we both smiled.

I said, “Geoff gets his comeuppance.”

She agreed, “He’s incredible.” (By “he” I knew she meant Jacko.)

I left it at that, for I, like Geoff, was somewhat lacking in vertical inches (in fact, Jackson had once called me “Huey Short” with a special chuckle which meant it had to be an in-joke of some kind). So I didn’t particularly want to go further into the subject of shortness with Justine, and I told myself that in any case I mustn’t burble on. Enjoy her presence but don’t expect too much, don’t try for too much, be calm, mature, realistic.... Have brief, light snatches of conversation....

“Here’s your flask back, Hugh,” said Justine suddenly. Now that she’d finished, was she going to leave me and go back to where she’d been sitting before? Paralysis took hold of my wits, but then a swerve of the coach distracted me from the pang of cold, lonely, childish, unreasonable grief.

The coach was taking us down a slip road to meet an eight-wheeled juggernaut hurtling blind on the inside lane of the motorway we were trying to join. I have no idea why the driver of the juggernaut did not see us; we must have been in plain view. Perhaps he’d just had a stroke or a heart attack and was unconscious at the wheel.

Others, besides myself, must surely have seen what was about to happen. Bryce certainly should have seen it; must have seen it. Perhaps he lost his voice in that moment of horror. You’d think, though, that one of us youngsters should have cried out – but no. You go on and on believing that ‘it can’t happen to me’ and you believe this because the grown-ups have always been in charge and we basically trust them with a trust and a certainty that refuses to get out of the way and clings even to the last crumpled fraction of a second with its rearing smash –

No pain. No darkness. Not even for an instant.

Instead....

>> 2: Awakening