Valeddom

2: awakening

I stared in a calm, mindless daze.

My brain was knocked out of play, by an abrupt and total shift of scene which quite shut down my power of thought. I could not understand, could not believe, could not absorb what I was seeing, and so, frozen in amazement, my mind left all the action to my senses.

When you wake up after a good night’s sleep, you sense that time has passed, but when you wake up after an anaesthetic, it’s like one moment they were putting the tube of gas against your nose and the next moment the operation is over. Hours may have gone by but you don’t feel as if they have. My return to awareness after the bus smash was of that sort, only even more peculiar. In fact, “waking” is hardly the word to describe it. Not even for a single moment had I really been unconscious.

On and on I stared. Presently, somewhere in my head, the reassuring sentence took form: “This must be a dream.”

I was crouching on the edge of a rough, natural stone platform, a slightly tilted slab, maybe five or six yards above ground level. My shadow stretched out before me; it lay enormous though faint, fading out over a rocky plain.

The plain was knobbly with hillocks and strewn with greenish scrub. Judging sizes wasn’t easy, but my instinct (that inmost part of me that knew this was no dream) urged me to estimate what cover was available, so I made a guess at the height of the vegetation – waist high to maybe six feet or so. Further ahead, jutting up from an oddly close horizon, grey mountains walled the plain.

The wildly strange thing about it all was the smouldering threat of light – lurking, ominous light. For though the landscape as a whole was actually somewhat dimmer than what we’d think of as a normal day, yet here and there perhaps half a dozen brilliant reflections from mineral surfaces hinted at some blazing snarl of intolerable brilliance at my back. Scared though I was, I could not resist: I had to turn to see where it was coming from. So I turned, and I heard my breath hiss inward.

In that other direction the plain went on only a couple of miles before it ran into another range of mountains. These closer peaks bulged blacker than the others. Heaving up in dark folds, this bulky rock-curtain was shielding me – I knew this immediately, without question – shielding me from the stabbing rays beyond. I knew it because the protection wasn’t total.

Like a raised eyebrow above a closed lid, an arc of red-gold fire shimmered in the sky above the summit line of the three closest and seemingly tallest peaks. I thought of the Northern Lights, I thought of cloud-reflections; but I was in no position to guess or understand. I told myself that anything is possible in dreams.

Worse, however, was what shone lower down, from just below the central peak of three.

Whether it was artificial, or whether it was a natural rock arch like the famous ones in Utah, the opening which gaped up there had a ceiling of quartz or some other polished mineral, and from it bounced a reflection which can’t have been more than a tiny part of the monster glare beyond it, but which was quite enough to dazzle me. I then realized that it must be this beam which was casting my fuzzy shadow.

At the moment things weren’t too bad, just rather awesome and severe. It wasn’t a nightmare – yet. However, it had the suggestiveness that can turn out to be the overture to horror. It’s a very good idea to nip that sort of thing in the bud. Disturbing motions, I often find, can form the start of the trouble. I wasn’t too keen on some twisting columns of steam rising from the nearer mountain slopes, and the quivering speed of certain scudding clouds.

“I’m too exposed, up on this rock,” came the woozy thought. “I must get down.”

Just by making my own move, I gave myself another fright: for as I crawled off the slab, and cautiously began to descend the slope of the little crag, my bodily activity drew my attention to my own physical self: the clothes I was wearing, and, inward from that, the appearance of my limbs.

I was in boots, shorts and vest. The clothes were of a greenish grey fabric which I couldn’t recognize – but worse than that, my body felt different. And it looked different. My arms and legs were rougher-skinned, and corded with muscle. My fingers were now extra skinny, the nails long, so that my hands seemed somewhat claw-like. And my size, I felt sure, had also changed; I was certain, despite having no other people in sight to make comparisons with, that I must be bigger and stronger – in fact I had no doubt that I now inhabited the body of a strong, tall, fully grown man.

Partly from the shock of this physical change, partly through general disorientation, I made a mistake. I stood up too soon. Losing my balance, I stumbled the last few feet off the rock. As I fell, my arms seemed to flail in slow motion and I experienced almost a sensation of swimming. I had time to think, make the most of this. I could try to make use of this fall to throw myself out of the dream. You know the sort of thing – you must have tried it yourself – you perform some violent move in the hope that it will rip the dream fabric apart and let you out. Well, the ground came up and walloped me, but not nearly so hard as it would have if…..

If what?

Propped on my elbows, waiting for my head to clear, I chewed on the unwelcome fact that gravity is something you can’t fake. If by some chance I wasn’t dreaming all this, then I had left Earth for some lower-gravity planet – and I could not accept that. Which made it all the more cut-and-dried that the dream option must be the only one.

Besides, that sense of meaning, that you get in dreams, was all around me. Surely that was proof enough. Surely, if I really had, in truth, been put into another body on another world, I would be more confused than this. I wouldn’t know a single thing. Whereas in actual fact dumb knowledge was sloshing around inside me like water in the bilges of a leaky boat. The more I reflected, the more I discovered typical urgent dream stuff: convictions which I had no logical right to have. For instance I felt the certainty not only of being on a strange and dangerous world but of being in a particularly dangerous part of that world. The landscape itself was frowning a message at me, telling me that I had strayed; that I was in the middle of trying to return to somewhere safer and I had better get on with it….

“Just be patient,” I told myself, trying to break the spell with flippancy; “eventually your subconscious must run out of ideas and then this show will be over.”

Still, in the meantime, there was cause for concern. Usually, you can wake up by trying to wake up. For instance you can mock the whole thing or throw yourself about, as I had just tried to do, until the thing bursts asunder. But those dodges don’t always work, and they did not seem to be working here. In which case, I told myself, I must accept the fantasy on its own terms for the time being, while taking sensible steps to stop it going really bad.

Well, what did I have to protect myself with? I wasn’t holding a spear (what made me think of a spear?) or gun or any other weapon. But I had something. I had that half-conscious knowledge sloshing inside me. How come?

I must be accessing the left-overs of that mind which had formerly inhabited the body I had usurped. A body obviously native to this world.

In other words, I was tapping into a source of local knowledge, and I had better listen to it. If it was saying “get out of this region, fast,” I had better do what it suggested. For this seemed to be one of those dreams with rules. If you flout the rules the consequences can be unpleasant.

I scrambled to my feet and let instinct direct my steps. In the first few seconds of my walk, without hesitation, I veered to avoid a large bush with dark poisonous-looking leaves, like those of rhododendrons but edged with spikes. It was the first of many such little detours. I noticed that I was not bothering to avoid all the bushes, just some of them. In general I kept to open ground as much as I could, as I headed at a slant away from the black mountains, putting distance between myself and the brutal light which hid behind them. With every minute that passed I was trusting my “native” self more and more to do the right thing automatically, leaving my own mind free to confront the mystery of where I was and why.

Most of me still insisted that of course I was in a dream, which had been brought on by those old space pictures I’d been looking at the previous evening. As a child had I not yearned, again and again, to plunge into those exciting landscapes? “And what happens,” I asked myself, “when you go to sleep in a state of badly wanting something?” The answer was obvious. You may well “get” the thing you want. Hardly surprising, then, that I found myself in a wish-fulfilment fantasy (though on the scary side), a fantasy of other-world adventure.

Except – I had difficulty in believing that I had fallen asleep during that coach trip. Hardly likely that I could have done that, with Justine sitting beside me.

But I must have.

Or….

I looked up and stared at the roiling, whitish sky, at the fast-moving ripples in the haze.

You can’t notice everything at once. But there comes a moment when the overlooked thing does get noticed.

I had thought that the plains were silent. Now I realized that this wasn’t so. A background noise, high-pitched, monotonous, had been screaming at me all the time. It was a very faint, continuous whistling wind, not around me but high above my head. That borderline sound…. because it was borderline….. told me a terrible truth.

The hugely faint, almost-inaudible atmospheric scream was evidence of the extreme thinness of the air. A fact I’d easily overlooked because this body of mine, this tough physique I was in, was used to it. Because I had to concentrate in order to hear it, it would have been a pointless detail in a dream. Far from being a show put up by my subconscious mind, the landscape couldn’t care less as it spread way away, choc-full of things I would never notice, and not at all bothered whether I noticed or not.

Minding its own business, as the real world is apt to do.

*****

Nothing shocks quite like the ghastly news that your wishes have been granted. Immediately, they are no longer wishes. They are the jaws of nightmare, biting down.

Trapped in this wish-fulfilment reality, I staggered as if I had been bashed with a club. I collapsed onto my hands and knees, moaning, no dream, no dream.

My mind slipped close to the edge of a dark, final, one-way whorl. Perhaps if there had been absolutely no answers, no possible explanations, I would have gone over that edge. Fortunately, I did have some notions that pulled me back from the brink. These life-saving ideas patted me with assurance that the universe hadn’t gone mad, nor had I.

I could guess that the coach had crashed – not a hard guess – and that I had been killed and my soul had migrated. For all I knew, this might be what always happened to souls. If so, it certainly contradicted what I had heard in church.

On the other hand, I very much preferred to believe that this was a special case, that my former self wasn’t really dead, and that somehow I might get back. At this very moment my old familiar body back on Earth might be lying in a temporary coma in Lancaster Royal Infirmary.

Whatever the truth might be, the most deadly moment had just passed. Insanity would never again be so close. I was safe at least from that.

I also benefited from some other advantages.

The mistaken idea that it was all just a dream had buffered me during the crucial first few minutes. More help could be expected from the knowledge which I had inherited along with the brain of this native body, knowledge which I trusted would reveal itself bit by bit as it was needed. Also, the normal young person’s zest for adventure was beginning to peep out, though, as you can imagine, it faced a constant struggle against dread and loneliness.

Finally there was that geography lesson. The very last lesson before my arrival here, had been the one in which Mr Bryce had led a unique discussion about habitable worlds.

“Coincidence,” Bryce himself would no doubt have said. “No evidence of a link!”

But I wasn’t handicapped by adult ways of thought. I didn’t ask for evidence. I just gratefully let the link exhibit itself. I needed all the faith, all the anchorage I could get.

*****

On I walked, over the lava plain, which was as smooth as chocolate except where it was cracked like dried mud. Often I had to step or jump over fissures which were up to a yard wide. The thin patches of soil around the bushes, and the whaleback shapes of boulders half submerged in the solidified lava, and the lava itself, were mostly all the same shade of chestnut brown. There was no grass though there was a scanty distribution of tiny poddy plants that in patches tinged the view towards green. The bushes were a darker, dull green. The only brightness anywhere was overhead, in the glowing pink rags of cloud which tore across the sky.

Eventually, a shoulder-high forest of bushes barred my way.

Coming up close to them, taking care not to touch the glossy serrated leaves, I saw there was no way through. A voice inside me urged me to be off. Heeding this inner knowledge, I turned. Now I headed south-east instead of north-east, still slanting across Yonnimay towards the night realm. Yonnimay. Flick! Like a darting fish the name had surfaced and was gone. I slapped the side of my head. No use, I couldn’t command these alien memories. They were lying low most of the time. Perhaps that was just as well.

By this time the sensation of low gravity was gone. I was no longer aware of any special lightness. If I had travelled to this world in my Earth body, like an astronaut, I would no doubt have continued for a long time to jump around and feel conscious of my diminished weight; but the muscles of the body I now inhabited were of course accustomed to conditions here. And so, after the first half hour, the mental novelty was worn away by physical custom, and I didn’t think about the gravity difference any more.

But other conditions – weather, temperature, air pressure – I did not take so much for granted. Mostly it was warm, but decreasingly so, and occasional freezing gusts swept the ground. The air, whenever I thought about it, seemed noticeably thin.

Hours passed. The black western mountains now looked far and small, and I was a long way out of the cone of light reflected from the high rock arch I had seen on my arrival. Now I was closer to the grey eastern mountains. Closer, therefore, to what lay beyond them, the realm of night – but only because I had walked towards it, approaching its fixed boundary, where it waited forever in the same place. Night, here, did not fall; day did not break – so whispered the knowledge within me.

Coldness increased, but, to make up for that, I more frequently came across warm springs bubbling in pools. A certain type of berry-bush usually grew by the springs. The first time it happened, I had a berry to my mouth before I knew what I was doing. It was as if the thing were broadcasting the thought “eat me, eat me”. So I ate it. And I got away with it. Imagine a combination of fig and sardine, if you can. Anyhow, it sustained me.

About the sixth pool I came across, I stopped in my tracks. Surrounded by crags and boulders, the area was dominated by a deeper-than-usual shadow. It was lit only slightly by the sky, by a faint light rising out of the pool – and by the reflection from a scaly hide.

My eyes made out the glistening bulge, curled up on the pool’s further side. Even from across the pool I could feel the warmth from the huge body. I began very slowly and quietly to back away.

As my sight adjusted further to the local dimness I saw that the scales were of a beautiful rose-green, and that the sleeping reptile, or whatever it was, might well be about fifty feet long. No, I wasn’t going to pick any berries from that oasis. For some minutes at a rapid walk I put distance between myself and the monster, which was the first animal that I had seen on this world.

Afterwards I slowed down and went cautiously again, still living from moment to moment, hardly daring even to think about making long-term plans. All I could decide on was another change of direction to edge me away from the realm of longer shadows, and back to the middle regions of Yonnimay.

During these wanderings I was never hungry. It was enough that I ate the berries when I could find them. Evolution on this hard world had produced an efficient metabolism, and my body seemed almost tireless.

My mind, however, got pretty nearly exhausted with doubts, loneliness and restless probing wonder. I tried to “listen in” to myself, to catch useful information leaking from the depths of my new brain. I needed native lore, but at the same time I feared to learn what it might tell me. Meanwhile my conscious Earth self rambled about, playing with ideas and possibilities, causing my mood to lurch and swing like a confused combination of see-saw and roller-coaster.

Yet really, I knew, perfectly well, where I was.

Time was on the side of the truth: with every passing hour, with no sign of sunrise or sunset, it was getting harder to imagine that this planet rotated. Besides, if it did rotate – if it had an ordinary day and night – how could life exist here at all? Nothing could survive the unspeakable radiation that lurked beyond the black silhouette of the western mountains.

Sunrise on Valeddom would mean death.

What was that word? Valeddom! Ring-tone of peril and majesty! A name which seemed to sum up all the beauty and isolation of the awesome little world on which I stood; a planet hemmed in by extremes of light and dark, hugged close by the void....

It was too much all at once. An engulfing wave of desolation and loss brought thoughts of my mother and father. I missed them so sorely that in the end I had to make a stern effort to block out the memory of them. Come on, be tough, I told myself. Besides, why despair? How could I be sure that my situation was hopeless? The vague hope that I might yet get back, with a great adventure to my credit, was impossible to disprove. How could I be sure of anything at all?

But then – what’s the use of being tough if anything can happen?

Then I remembered one of Mr Bryce’s pet phrases. His standard rejoinder to anyone who put an unconvincing case:

“This,” he would object, “is not intellectually satisfying.”

(So we, his pupils, amongst ourselves, when arguing about whose turn it was to play goalkeeper, or who was going out with whom, would put on a pompous voice and say “tut-tut, that’s not intellectually satisfying”.)

Well, thought I, if Bryce were here now, he would certainly use his phrase on me.

For it was simply not true that “anything can happen”! I wasn’t stuck in some chaotic dream. I was in a place with natural laws and rules. Admittedly a place of mystery, but hard, solid and real.

How soon we get used to things, how soon we realize that every place has its own rules, how soon we accept those rules as normal for that particular place! Of course, adaptation is essential for survival – we wouldn’t last long if we went around in a continual daze of astonishment – but all the same, when you find yourself on another world in someone else’s body and you still find yourself getting used to it, I think you’re entitled to call it an extreme case of adaptation…. Truly amazing, how soon we stop being amazed.

Lonely and homesick though I was, I was coping (just about) with the help of that extraordinary adaptation gene, plus the “native residue” lurking deep in my brain. And yet, I was in a fix concerning that “residue”: I wanted to access it – I needed native memories for survival expertise – but at the same time I dreaded to awaken that stuff too much, lest I cease to be me.

Yet even this fear, the fear of loss of personal identity, was something I was getting used to.

I was coming round to the view that this native self was me.

Yes – just as much as my Earth self, my Valeddom self was me. So – both of them were “me”; but how?

I began to figure it out.

Rich people can own a second home.

Souls can possess a second body.

Maybe the fully conscious mind can only inhabit one of them at once, while the other is maintained by a caretaker fragment of soul, living a humbler life; or maybe both lives are equally conscious; either way, it could be that when something unusual happens, when one body gets knocked into a coma by a bus crash for instance, its mind has to relocate, to take up residence in the alternative home.

I could therefore reasonably hope that I wasn’t a murderous usurping parasite after all. Even if my arrival had suppressed another consciousness, I had an excuse – I was merely taking over a second self.

The idea rang so true, I wondered if it was another of those bits of native knowledge I was dredging up.

“No,” I could imagine Bryce saying, “theories that can explain anything are too easy. Not intellectually satisfying.”

Doubt swooped upon me. Was I fooling myself? Pretending to know? Giving too much credence to the whispers in my head? Deluding myself to hide the fact that I really understood nothing at all? If so, then I was lost.

Down tumbled my mood, my roller-coaster mood, once more towards despair.... I had to stop it.

“Rubbish,” I objected. “You ought to be ashamed of yourself! Think about heroes! Men like Sir Thomas More or Sir Walter Ralegh who said witty things even on the scaffold! If they could face decapitation, surely you can face being marooned! You’re alive, aren’t you? You have the berries to eat, haven’t you? And you don’t know the end of the story, do you? Pull yourself together.”

*****

Something interesting drew my attention: I was following a kind of trail.

It was a barely visible trail, not marked like an actual path on the rock plain, but signposted by occasional little cairns or alignments of stones which seemed (to my native eye) to point to convenient passes between the crags and bush-forests. Was it the work of intelligence, or could animals, following some kind of instinct, have left these signs? The trail was gradually causing me to veer again towards the night side of the world…. I wondered, did life on Valeddom have a preference for the dark edge of Yonnimay? Might creatures tend to avoid the monstrous sun, more than they shrank from the freezing waste of Darkside? Maybe I was jumping to conclusions, seeing one side of the ecology; if I were closer to Brightside I might find salamanders or suchlike beings which could endure the heat and light. If I could lift the lid just a bit on my native knowledge, I might learn.... and immediately my thoughts went back to the huge reptilian beast I had seen by the pool; its hide had emitted a blast of warmth, and I suddenly had a hint of its symbiotic purpose as a heat-distributor, and from there I zoomed to a sudden general picture of every possible niche as crowded as could be, in the solitary ribbon of life that was Yonnimay, the Twilight Belt of Valeddom. At this glimpse and taste of immensity, I hurriedly slammed down the lid on my native store of knowledge which threatened to swamp and overwhelm me, and I retreated to my ignorant Earth self.

A rattling, of many loud clicks, broke out ahead of me. I froze, not daring to move. My mind was a blank with nothing to go on. I had just rejected knowledge. Now there was something up ahead and what should I do about it?

I considered running for cover among the small crags and boulders that jutted like house-sized teeth up through the lava. But to run might be to draw attention to myself.

Finally, with the utmost caution, I advanced.

On a clear area of plain beside the trail, I came upon a group of about a dozen barrel-sized, bulbous vegetables, ridged like cacti. They had twiggy tufts the size of chop-sticks growing from their tops; the rattling sound came from these sticks tap-tapping.

I ventured closer still. I’d never learn what’s what if I avoided every off-putting thing. I stopped at three yards and watched the twigs make their noise. My tension eased as I came to the conclusion that the rattling was purely defensive, evolved to ward off predators. So, having had my look, I returned to the trail. For a while I still heard the click-click-click behind me.

In my imagination the noise began to seem like an exchange of remarks, and the sick eerie hunch that those blind isolated things might be talking made this world seem infinitely lonelier, its nature so remote from anything I was used to... And I couldn’t dismiss the suspicion of plant-talk: for I had no way of deciding whether it leaked from my knowledgeable “native” brain or was conjured up from my ignorant Earth fancies.

The trail rose and dipped; it was surmounting a short pass through an east-west spur, towards a point where the main scarp on my right came to a sudden end. Beyond, instead of the usual jumble of crags and rocky domes which for some time had obscured my view of the Darkside horizon, that horizon suddenly appeared uncluttered, sharp, close – so close that, looking to the right, I felt as though I were about to fall off the edge of the world. I stopped to stare, before descending the last few strides to that dim plain.

A squall of rain burst around me, one of those violent but short-lived downpours which last typically less than a minute in Yonnimay. They descend as a steamy mist when close to Brightside, and fall as snow at the actual border of Darkside. Just here, the rain was warm and couldn’t harm me, so I sought no shelter but simply waited for it to stop. Visibility dropped close to zero as the water lashed down in sheets, yet I could make out a manlike figure nearby.

The fellow was leaping down from the last craggy outpost of the spur, to try for a dash across the open space ahead.

Obviously the humanoid was using the rain as cover, but then the rain stopped as abruptly as it had begun, and immediately, as it sprinted across the plain, the figure became exposed. I saw where it was making for: a low crinkle, a solidified wave in the ancient lava, no higher than the breastwork of a military trench.

I remained motionless, frozen in a mixture of anxiety, hope and caution. And then I felt a blast of heat as another and far vaster shape plunged past me, bounding off the crag in pursuit of the fleeing humanoid.

I had an impression of gleaming scales on a vast hide, and perhaps eight legs, side-on like the legs of a lizard. It could even have been the same huge creature that I had seen earlier asleep beside its pool. Then the thing hit the ground, and sprang once more in the direction of its prey.

The fugitive in its terror became less man-like; it started to run on all fours. By doing so it increased its speed, but to no avail. The great head of its pursuer snapped sideways – its outline in that moment like that of a shark’s head - then its jaws gave one crunch around the body of its victim.

A ragged chorus of yells yanked my attention to perhaps ten or a dozen humanoids of assorted shapes and sizes who leaped from the shelter of the low crinkly ridge which their unfortunate confederate had failed to gain. This was obviously a hunt that had gone wrong: the one chosen to decoy the monster had made a fatal mistake in his timing; it remained for his companions to avenge him.

They charged forward, brandishing spears. The giant lizard watched them come. It was slowly waving its head; then, to my surprise, it retreated a step.

The hunters advanced with such rapid dodging motions that I couldn’t get a detailed look at them. I stared and stared and at last I unfroze and made a move – sideways to the shelter of a fold in the rock-spur. Having seen the lizard in action I couldn’t see how even ten hunters could hope to overcome it. Evidently, though, these natives were confident and their blood was up. Their loud cries had ceased; now they clacked at one another and jabbed their spears forward in what seemed to be a concerted plan of attack. It occurred to me that there might be something special about those spears. Something of which the lizard might know more than I did; anyhow the giant beast was shuffling backwards. Then it turned, and, lashing its tail in defence, plodded past the little hiding-place where I was pressing myself back into a fissure….

The pursuing hunters passed by me, and I got a good close look at them. It was at this point that I noticed their variety. Two or three seemed human, or almost human, with faces that could have passed unnoticed in a crowd on Earth, though their hands, like mine, were skinny-fingered and clawlike. The rest ranged from the misshapen to the downright hideous (in human terms, at any rate); the smallest were the ugliest, naked, scaled, gnarled and with protruding eyes and fanged mouths, altogether like reptilian gargoyles. And yet there seemed to be a kind of kinship among the whole wide range of them, as though they all displayed stages in a continuous spectrum of development – or degeneration.

Stunned and dismayed, I couldn’t suppress the frightful thought, that I was one of them. All right, I was taller and straighter than most – but what was that worth? Hope and pray, I commanded myself, that the differences are important.

I waited until the hunting party and their quarry were out of sight – though I could still hear them – and then I left my hiding place. Subdued by what I had seen, I emerged from the pass and stepped quietly over to the body of the dead humanoid. Enough of the torn corpse remained to show me that it had been about midway in the scale of degeneration between the more manlike hunters and the gargoyles. It had run on all fours during its last seconds of life, an adaptation which hadn’t done this poor creature any good.... I grew depressed at what I had met so far: super-plants, giant heat-lizards and sub-humans. Was this a world where man, or the man-shaped race, was destined to fail?

Then I looked at the eyes, and saw that they were covered by a sort of thin film, and it was this last detail which caused a lot of other impressions to crowd together in chorus, whispering to me a momentous conclusion:

I wasn’t the first Earthling to get here.

Clark Ashton Smith, in his classic “The Immortals of Mercury”, had described creatures just like this.

Well, not quite. The context was different; Smith had made no mention of the spears, and besides, it was only the smallest and ugliest of the creatures that closely resembled those in the story – the beings called the “Dlukus”.

I stood there, arguing with myself.

What was my mind playing at? Why assume that Smith needed to have been here? Certainly there were links between the worlds – otherwise I wouldn’t be here. But in literature those links might consist of mere spillage, the seepage of dreams.

Be that as it may, it was reasonable to suppose that what had happened to me, had happened to others. And some of those people might have written down their experiences.

If this were true, if some had returned to tell the tale – even if they felt obliged to disguise it as fiction – then there was a way back to Earth!

Cheering though this thought was, and helpful though it is to give names to things, the attempt to fit stories onto reality could turn out to have depressing results. I didn’t at all care for the idea that I might meet more creatures out of the fiction I had read. Perhaps I could cope with the Dlukus, but I certainly couldn’t afford to meet Smith’s “Immortals” – a hostile super-race of ruthless scientific wizards. My life at the moment was quite interesting enough.

What must be accepted, was that there was no room for argument as to where I was. Already I had known it instinctively; now the weight of evidence had increased to the point where I must admit openly, that the Twilight Belt version of Mercury had all along been the true one. The storybooks were right about that, whatever else might be mere imagination.

You might shake your head and say, hang on, the “evidence” only showed that I was in a world with a constant day and night side, and such a world might be anywhere in the Universe.

But no. Mercury it was. The final, spooky confirmation was within me: innate, inherited knowledge. For hours I had postponed the step of looking it fully in the face, but the time for evasion was over. Luckily, being young, unencumbered with an adult mind, I had the sense to realize that even if the truth was crazy, my brain must accept an armistice in any fight with reality. Later, insights and explanations might be gained, but right now my aim was to survive.

All these thoughts fairly rushed through my head as I sought to decide: should I turn back and catch up with these Dlukus and try to communicate with them, while I still could?

Under pressure, I almost made a fatal mistake.

I told myself that here was an opportunity that must not be lost. Here at last were people. Primitive and maybe savage people, but still people. I shouldn’t let them disappear in the wilderness without making some effort at contact; I should follow their trail now, while I could still hear them.

Another thought: supposing one of them got killed in the fight with the lizard, it would leave a spare spear, and I wanted one of those spears. At one time I must have had one of my own. Thinking about it, I could guess how I had lost it; I could picture the scene:

A lone, novice Dluku, wandering through Yonnimay, realizing, perhaps, that he’s strayed rather too close to Brightside, climbs onto a rocky platform to spy out the land. Suddenly a shock slams into his mind. It is his Earth self – it is I – that has descended upon him, obliterating his consciousness. His spear drops from his hand. It falls, forgotten, to the base of the rock, somewhere to the side. No doubt it is still lying there….

I wasn’t going to go back for it, but it was worth making some effort to gain another. Any hand-weapon that could repel a fifty-foot monster was to be recommended in this environment. So I doubled back in pursuit of the hunting party.

Not too close a pursuit: I did not want them to see me while the hunt was still on. I found it possible to keep within earshot of their harsh clacking speech as they wound their way through the boulder-strewn landscape in pursuit of their retreating quarry.

Then I suddenly heard a renewed rattling of the cactoids. Next minute I came upon their grove once more. I halted, appalled. My stomach seemed to squelch with horror.

What must have happened was obvious. The retreating lizard, thrashing about with its tail, had wrecked one of the plants, shearing half its barrel-shaped body away. And what I saw inside that vegetable corpse was – I can hardly write it –

A brain.

There wasn’t any doubt about it. The dregs of Mercurian knowledge inside me confirmed what my eyesight told me. A greyish spongy mass sagged and oozed helplessly in the cactoid’s exposed cross-section. A plant-brain.

No wonder they “talked”. Yelling grief and pain! Or were they?

A plant, I assured myself, has no nerves, feels no agony. Ah, but an intelligent plant might experience mental suffering. Or if it was dead – and surely it was now dead – its relatives must grieve (I could not help thinking in human terms to some extent).

My ideas then took a peculiar turn and instead of being angry at the careless hunters and the lizard I was suddenly furious at the victims. What business did a plant have, evolving intelligence? Just to stand there and think, without eyes or ears or hands – what kind of life was that? But then, I wouldn’t know, would I? I couldn’t possibly ever know what mysterious, compensating senses an intelligent plant might have.

Anyhow this shock had done me a favour. It had distracted me from following the hunters. It gave me a chance to re-think my plans. In particular the sight of that huge brain, sickening though it was, gave me the jolt I needed, to acquire a healthy distrust of the native sludge at the bottom of my mind. Aha, I thought, I’ve caught you out! I realized now that this Mercurian mental residue had been pushing me towards joining the hunters’ band because it wanted me to evolve (or rather devolve) more and more towards the Dluku state. It was biased that way. Perhaps I was jumping to a mistaken conclusion, but I didn’t think so; I reckoned I had chanced upon a real danger: my native instincts, which I had found so useful, had their own agenda and couldn’t be trusted. If I joined that Dluku band, I’d end up like one of those gargoyles myself.

And there was another way, a far better way, to find companionship.

For starters, how about using a bit of common sense? All this time I had been carrying around with me – I had been actually wearing – the proof that I needed, that somewhere on this planet there should exist an advanced civilization.

I fingered the fabric of my shirt and shorts. Despite their grey-green fake-leathery look they weren’t skins, as I could tell when I examined them closely; nor did they seem like linen cloth. They seemed like some sort of artificial fibre. At any rate they weren’t the sort of stuff I could imagine being produced by the Dlukus. For that matter, the same applied to their spears. I was willing to bet that some very different order of being had provided such primitive hunters with those weapons.

So I ought to set my sights higher. And trails lead somewhere, don’t they? All I had to do was persevere – and avoid the miserable thought, that perhaps the clothes and the spears were merely relics left behind by a vanished culture.

My Earth instincts and my Earth logic had gained the upper hand, none too soon.

*****

On I went, resuming my previous course, away from the lizard-hunters. I was now in a more thickly boulder-strewn region of plain. My senses were on the utmost alert: anything might be hiding amongst all the cover which the great stones provided. Yet though lacking a weapon, I felt strong and able to run fast, provided that I wasn’t taken by surprise and grabbed; as for monsters like the lizard, any such thing would be so huge that I’d be able to see it in good time even among all these rocky obstructions.

What bothered me more than danger from wild Mercurian beasts was that thought which I was trying to avoid – that the degenerate Dlukus might be all the people there was, with civilization a thing of the past.

That sad idea took hold, the more I tried to avoid it. How careful you need to be with your thoughts in an alien environment! You can so easily mislead yourself. It’s like those dreams where, if you don’t watch out, you summon the thing you don’t want, simply by thinking about it.

It was while in this state that I came upon the Clearing of the Caches.

No doubt you’ve seen, in a little fenced-in plot now and then, sometimes between houses in an ordinary street, those electricity box-things, I think they’re called “substations”, the size of phone booths. The objects I now saw reminded me of those, though they weren’t fenced in. And they were taller, roughly the size of the monoliths of Stonehenge, but of grey-green metal. There were five of the structures, spaced in a circle. They stood about twenty feet from each other in a smooth space that had been cleared of boulders.

And in the clearing, sitting cross-legged or standing about, were eight Dlukus. They weren’t too ugly; they were at the human end of the scale; but there was a dazed, vapid look about them. None of them were holding spears, though a few spears lay about the ground nearby.

The sitting ones were eating out of their cupped hands; some of the standing ones were just mooning about, nibbling pellets of food or exchanging the odd phrase in their clacking language, and one was stroking a spot at about head height on one of the tall structures. As I watched this particular Dluku, I saw an opening suddenly appear in the structure and the Dluku reached in and extracted some pellets which it began to eat.

I stood back and watched in dismay. This was just the sort of picture that I didn’t want to see: savages loitering among ruins.

Or not ruins exactly, since the caches were functioning; not ruins but relics, deliberately left behind by the old civilization, the last gift of the wise old Mercurians to their dumb successors, to help ease the transition, to smooth the downward path....

And was that my path, too? I advanced into the circle, and the Dlukus must have seen me, but they took no notice; I was so obviously just another Dluku.

I stood in the centre and turned around, looking at all of them. Then I took a deep breath and resolved to make a serious effort to communicate.

I summoned the language I needed, by picturing it seeping up like water, upwards through a rock-layer and into a well. In this way, greeting-words welled from some deep place inside me into my conscious mind, and I spoke them:

“Junnd! Zral! Yaer!”

Some of the Dlukus looked round at me. One or two of them said, “Zdak!” which I immediately understood was their debased version of the second word I had uttered. Then they returned to their food.

End of conversation.

I shrugged, went over to examine one of the caches, and blundered into my next shock. What appeared to be an inscription in English made me reel back in astonishment. Had I been transported centuries into the future to a time when Mercury had been colonised from Earth? Had some disaster then caused the colony to regress? All this nonsense was blotted out by my second glance at the so-called English words. They were nothing of the sort. They had fooled me for a moment because I could read them. But that was only because I had been reading them with my Mercurian mind. Now that I was prepared for the sight of them I could see with my Earth mind how alien they looked – a combination of spirals, quivery lines, and sagging squares, and yet I was reading it, translating as I went along:

Ixlian Mercy Station

Annual Replenishment

“For Honour, For Ever”

Follow instructions on diagram

…Annual replenishment! That phrase had a promising sound! It strongly suggested that at the very worst I need wait no more than one Mercurian year – and that was only eighty-eight Earth days – before someone came to put another store in the cache. Someone from civilization! Someone for me to relate to, talk to! Due to come here! Relief surged through me.

My eyes travelled to the diagram below and I soon got it figured out. With high hopes, I pressed the indicated points.

A door seven feet high swung open, revealing inner panels and the inside metal surface of the door, so polished that it was almost as good as having a bathroom mirror. Using it as a mirror, I stared for the first time at my own Valeddomian features.

*****

I stood there for some minutes, getting used to the truth. I looked nothing like I did on Earth, but I still looked human. In fact with unwilling amusement I had to admit I was a lot handsomer as a Mercurian than I had been as an Earthling, at least as far as the face was concerned – my features were strong, regular, and wore a look of knowing calm which concealed my inner turmoil.

However, I decided, after many glances, that I didn’t, after all, much like that look of calm. It seemed over-relaxed. I put on a grimace, deliberately making faces at myself, but that calm look kept flowing back: a bland, ominous smoothing of the features. Over the very long term, I was sinking into the dopey, vacuous state of the Dlukus.

As a Dluku I might become a great hunter of lizards. But I’d much rather be Hugh Dent, a weakling with a human mind, than have the strength and the mental horizon of an ape.

Admittedly, I did like the size and toughness of my Mercurian body. It was certainly handy to have acquired a physique without having to go through the bother and boredom of body-building. But I suspected that around here such strength was merely the norm, and conferred no special advantage – in which case it would be a bad idea to get too excited about it.

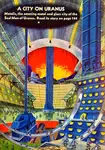

The sensible thing, I decided, was to pin all my hopes on the arrival of the people (whoever they might be) who kept the caches replenished. Civilized folk would surely understand that I belonged with them. They would take me away and I would live in a great Mercurian city somewhere. I yearned for company, real company. The Dlukus were hopeless; they would always be hopeless; I knew this by means of the same inside knowledge which told me that I was slowly sinking into that subhuman state myself. A radical change of environment might arrest the process – otherwise I was doomed.

I remained at the Mercy Station, sleeping stretched on the ground among the caches when I got tired, with a stone for a pillow. The Dlukus did the same, when they felt like it. I had no fear that predators might creep up on me unawares during these sleep-periods. For one thing, some of the Dlukus were always awake, and they had their spears. Also, a bit of scouting around showed me that a short way away in three directions stood some of the giant “brain-cactoids”, and I guessed that they had been placed there to produce their rattling warning signal in case of danger.

I learned to open the panels and extract the stored food. The stuff was like slabs of dried dates only less tasty. I looked into the other caches and found other supplies: spare clothing and racks of the spears which I had seen belonging to the hunters. I took one of these weapons for myself. Also there were a few gadgets, most of which I could not fathom the use; but among them was a tool, beautifully made, which I could identify easily: a pair of binoculars. The pressure pad which acted as focuser was like nothing I had ever seen on Earth. I was amazed that this wonderful device had been left unclaimed. The fact confirmed my low opinion of the creatures hanging around this Mercy Station.

I say that I knew that the Dlukus were hopeless; however, I don’t want to give the impression that I despised them totally, nor that I completely gave up trying to learn from them.

I thought to myself: “If I could catch one in the very early stages, and question it, maybe I might find out something vital.”

I had plenty of them to study, for they came and went, and new faces kept appearing in every waking period.

The “youngest” Dlukus, the most human-looking, were quite dignified and grave in their manner, though confused and bleary. When I greeted them, pointing at myself and saying my name, they never told me their names in return; I wasn’t sure whether that showed they didn’t understand my question, or whether they didn’t want me to know their names, or whether they no longer had names, or whether they didn’t care. But they would occasionally take it into their heads to speak some stunted sentences to me. When this happened, I heard them use a tongue which did not clack like those of their more degenerate brethren.

“Who left us all this food?” I once asked.

“Ixli tmetl coming soon.”

“What is Ixli? What is a tmetl?”

“Ixli tmetl coming soon. But no need for much more.”

“When will this happen? When will Ixli tmetl come?”

“Yonnimay wide. No bother, hours, years.”

No bother indeed, I thought grimly. A melancholy picture built up in my mind; a picture built up, as usual, to some extent out of what I call the Residue – the dregs of my Valeddomian consciousness – and to some extent out of my own Earth logic:

“Somewhere,” I muttered, “in this Twilight Belt, somewhere in Yonnimay, there must be a Mercurian civilization. I am sure of that now. But it is a civilization with a downward pull.” I went on in silent thought: Every so often a few of its people must experience an inner summons to abandon their human status, to leave their society and go into the wilderness, where they begin to revert, physically and mentally, to the semi-human Dluku state. But civilization does not completely forget them; the Mercy Station is maintained here where many trails meet, and the caches of food are replenished, and spears are provided for defence and hunting.

It was a picture which made its own kind of sense, though it raised as many questions as it answered. It justified my decision to wait where I was. I wished I knew what a tmetl might be. Something big, said the whispering Residue. I needed more information than that. I needed greater amounts of the Valeddomian language to well up from the lower depths of my brain, but it didn’t always come to order. Trying to force it up could be as frustrating as trying to listen to a radio broadcast half-smothered in crackling interference. All I got of the meaning of tmetl was the blurry idea of a moving length and of many voices.

But at least it would be big and organized.

So when, one waking period, standing atop a lookout post I had arranged for myself on a climbable boulder, I espied through the binoculars a solitary man approaching the Mercy Station, picking his way along the rock-strewn path from the south, I didn’t think that anything important was about to happen. All I saw, at first, was just another Dluku.

Perhaps an older, wilder Dluku, come to see how the new lot were getting along? Or a proper human wanderer? I had no idea. The man was even taller than I, immensely strong and rugged-looking, with a bushy brown beard. He was as impressive as a barbarian chieftain out of some epic tale, except that the smooth artificial fabric of his shorts and shirt didn’t fit that picture. He carried a spear, but he rested it on his shoulder as if he were a rifleman on parade. When he came to one of the brain-cactoids, part of the “early warning system” surrounding the ring of caches, he stopped and stared at it with a look of alert excitement on his face. The cactoid stayed quiet. It did not see this stranger as a threat.

The big man continued to peer about, cautiously. Aha, thought I, he’s actually (despite his size and tough appearance) the most hesitant, the most puzzled of the lot. So here’s a Dluku in the very earliest stages – here is something important, after all; my best chance so far to get more informed, be ready when the tmetl arrives. Or – I thrilled – could this even be the advance guard of the tmetl itself? No Dluku at all, in that case, but a civilized man, though possibly a rough frontier type, habitually wary.

I scrambled down and strode out to meet him.

I had advanced about thirty yards from the clearing, when he saw me. He immediately grabbed his spear two-handed, bringing it round to clasp it quarterstaff-style. I halted, maybe five yards away from him, awkwardly aware of the fact that I had left my own spear behind. Careless, careless, I chided myself.

Words rumbled from the big man: “You walk with purpose.”

It could have been a compliment, but he growled it like an accusation.

“Welcome to the Mercy Station,” I replied fluently in his language. It seemed a harmless thing to say.

The big man shifted his spear, thumped the butt of it onto the ground.

Perhaps triggered by the vibration, the cactoid’s sticks gave off a sudden, brief rattle.

“And what,” continued the man indignantly, “is this fat thing?” He accompanied this demand with a fierce gesture towards the plant to his left. To my astonishment I could read panicky outrage in the blaze of his eyes.

Things happened quickly after that. We were both so much on edge, we were like kegs of dynamite ready to explode. I was completely taken by surprise – ambushed by my own fury as well as by the big man’s. How easily can fear and the anger of long tension made people stupid. But I had the less excuse.

“Why ask me?” I replied; “don’t you know about the brain-plants? – Hey, don’t do that!” I cried unthinkingly in English as he jabbed at it with the butt end of his spear.

Louder rattle! Sudden squawks and clacking din as the Dlukus from the clearing cried out to each other and rushed to see what was happening! I sensed them gather at my back, but I dared not turn to look. I dared not take my eyes off the barbarian oaf.

For quite some while I had been working out a script of how things were supposed to happen: a civilized and wise group of beings must come from some great Mercurian city and rescue me. Instead of which there was this confused savage, who for a moment I had vainly hoped might be a scout of the glorious tmetl.

The disappointment was too much.

Sometimes the price we have to pay for adaptability is excessive. Though we surround ourselves with a wall of comforting ideas, the upkeep of the wall can get too costly. Tired, brittle and impatient with the slow trickle of information from the Mercurian Residue in my brain, I had let myself take the risky short-cut of believing in science-fiction. Particularly, in impressive alien civilizations…

“You’re not supposed to poke around like that!” I yelled in absurd frustration at his spear-play. “You know better than that! This is an ancient world; you’ve had millions of years to learn to put up a better show!” Hard to believe, but I really was dumb enough to babble on in this ridiculous vein as I poured out my resentment at all the bewilderments heaped on me since the bus crash and my awakening on Valeddom. Stock science-fictional images flooded my brain: “Where’s the hovery slidy sled, you idiot, where’s the studs you press to blast, the clicky-communic, eh, and vroom, swish, you know – ” On and on and on I spouted. For a while I was beyond noticing that I was now yelling in a mixture of English and Valeddomian, and that the big man, yelling back, was doing the same.

He stopped before I did. He began to smile behind his beard. I at last cottoned on to his change of mood. I sputtered to a halt.

In the silence that fell, I noticed that the cactoid had stopped its rattling and the Dlukus had gone back to the clearing. For them the alarm was over. They had lost interest.

The big man’s smile trembled on his lips. Warily, as if explaining a controversial joke, he said:

“I apologise for hitting the plant. But I get annoyed when things don’t make sense. What reason does a plant have to develop a brain? The whole notion is just not intellectually satisfying...”

“Mr Bryce!” I burst out. “Mr Bryce!”

He nodded, “And you – I dare say – you’re someone I know? Ah yes; you’re unlike the rest of the cast of this dream.”

I saw the grin stretch too wide on his face, and then I understood that he had had a worse time than I.

I blasted more English words at him.

“I’m Hugh Dent! We were both in the crash, remember? This is no dream! We’re now on Mercury – Valeddom, it’s called – and we’re in Yonnimay, its Twilight Belt.”

The grin disappeared. His face sagged. I could almost hear him thinking what I myself had been thinking so often: oh to meet someone who can really talk to me! And is this a con? Am I being fooled?

“Come on,” I coaxed. “You know better. I bet you’ve got the info sloshing around in your head, same as I have.”

That “sloshing” was what finally got to him. He raised his eyes; he chuckled. The chuckle became a loud laugh.

For the next two or three minutes we went mad as footballers when one of them has scored a goal: jumping around, hugging and thumping one another. Then the wonder of it all took hold of us even more firmly and we went silent and still.

Both of us, I dare say, were thinking the same thing. Even more important than the end of loneliness, was that now we each had the other for an ally in our contest with the unknown. The whole outlook of the game had changed. We might win it. We might survive. We might meet the other victims of the crash. Since two of us had ended up like this, wearing different bodies here on Valeddom, why not more?