kafka's

crystallization of hooked time

by

antolin gibson

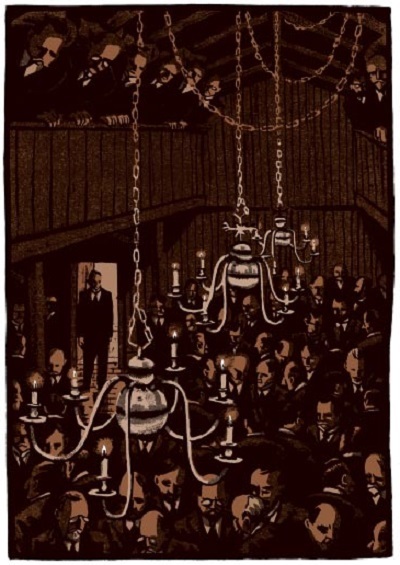

The Trial is Franz Kafka’s most famous work, and it is the great novel of time and ambience hooked back, in order for the author to focus upon the experience of one human being: time and place are not allowed to trample the quintessence, the horror, the actuality of this experience.

In the words of Clark Ashton Smith, little enough is known “of that elusive, ineluctable process whereby the present becomes the past and the future resolves itself into the present. All men have pondered the riddles of duration and transience; have wondered, vainly, to what bourn the lost days and the sped cycles are consigned. Some have dreamt that the past abides unchanged, becoming eternity as it slips from our mortal ken; and others have deemed that time is a stairway whose steps crumble one by one behind the climber, falling into a gulf of nothing.” (The Chain of Aforgomon).

Franz Kafka, in his works, is the very necromancer of time. It is as though he kills it, only to bring it back to life - a life hooked back to his sensitivity and his will, frozen, so that the actuality of experience is crystallized, scrutinised, explored – obsessively, minutely, truly.

This focus is so vivid and extraordinary that it is like a rictus of horror and fear. By its murky glare, reminiscent of Milton’s Paradise Lost - “No light, but rather darkness visible/ Served only to discover sights of woe” - even the illusive betwixtness-and-betweenness of humdrum life is suddenly laid bare, contoured as never before.

The act of compiling experimental parallels to The Trial becomes addictive. It can make curious reading in all the diverse crossings of media and themes:

The Scream – Edvard Munch.

The Wrong Man – Alfred Hitchcock.

Little Dorrit (the Circumlocution Office, in particular) – Charles Dickens.

That Hideous Strength (the Belbury of the “N.I.C.E.”, in particular) – C. S. Lewis.

A Matter of Life and Death – (the

Heavenly Trial)

Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger.

The Seventh Victim – (the Diabolic Trial) Mark Robson and Val Lewton.

Alice in Wonderland (the Trial Scene, in particular) – Lewis Carroll.

The Prisoner of Chillon – Lord

Byron

(“It was at length the same to me/Fetter’d or

fetterless

to be/I learned to love despair.”).

The Prisoner – (the theme therein of “Mutuality”) - Patrick McGoohan.

Pensées (“The eternal silence of these infinite spaces frightens me.”)

– Blaise Pascal.

Labyrinths – Jorge Luis Borges.

Kafka is perhaps closest to Borges: similar to both are the mystic parallel to history and the chaos of the conundrum. Borges’s Labyrinths is echoed in Kafka’s Before the Law. Borges’s Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius is one of the most important tales ever written on the subject of the existential link between fantasy and reality and what Tolkien called “sub-creation” – all very relevant indeed to Kafka. History real or feigned, was for Tolkien as one value, and it is this idea of “sub-creation” that haunts the works of both Borges and Kafka: the concept that, just by the composition of words, an existence – an absolute creation – a reality is manifested: concurrent (or, in the case of Borges’s “Tlön”, superseding) Clark Ashton Smith's aforementioned “riddles of duration and transience”. Thus we have the very soul of myth and history. “Print the legend”, to quote from The Man who Shot Liberty Valance. The forty volumes of the Encyclopaedia of Tlön will expand to one hundred at some future time. The human result of this, is that human identity is on Trial. And it is here that Borges touches Kafka most truly. In the essay, The Fearful Sphere of Pascal, Borges – after contemplating the depersonalizing “perfection” of the sphere – remarks on the anguish of Pascal:

“He deplored the fact that the firmament did not speak, and he compared our life with that of castaways on a desert island. He felt the incessant weight of the physical world, he experienced vertigo, fright and solitude, and he put his feeling into these words: 'Nature is an infinite sphere, whose centre is everywhere and whose circumference is nowhere'. Thus do the words appear in the Braunscheig Text; but the critical edition published by Torneur (Paris 1941), which reproduces the crossed-out words and variations of the manuscript, reveals that Pascal started to write the word effroyable: 'a fearful sphere, whose centre is everywhere and whose circumference is nowhere.'

“It may be that universal history is the history of the different intonations given a handful of metaphors.”

The Fearful Sphere of Pascal, Jorge Luis Borges.

How Kafkaesque is all this: as though Borges is the philosopher and analyst of the human and metaphysical conundrum of which Kafka is the bewildered explorer – still, this is more a variation of emphasis and style than substance and intent. A Pascalian suffering and questing is central to both Kafka and Borges, be this emotional or intellectual. The boundary here is as blurred as that between myth and history. As ever with such intangibles, it is refreshing to go to Emily Dickinson, who has the gift of hitting intangibles on the head – gently!

“There is a pain - so utter –

It swallows substance up –

Then covers the Abyss with

Trance –

So memory can step

Around – across – upon it –“

Emily Dickinson, Poems # 599

Be it emotional or intellectual - and both Borges and Kafka lap over the boundary-line - the intent, the passion of focus, is dominant in both. This focus is a crystallizing significance of fleeting experience from the surface-moment of time. It is the very factor of time. Time haunted Kafka, and I don’t think this can be put too strongly! The focus upon the actuality and implication of experience is, for Kafka, All. He crystallizes against the flow of time and makes his stillness amidst – and not according to – necessity. Of course, one could say this is true of many a fantasy and SF writer, Mervyn Peake and Cordwainer Smith and Lord Dunsany and Philip K. Dick come to mind, who create new worlds entirely distinct, and hook back from so-called reality, and freeze, to the quintessence – of whatever obsession they may have as writers. In Dunsany’s case, I think the obsession was purely escape. But neither Kafka nor Borges have the peculiar Dunsanian justification – and blessing – of such an escapism.

After The Trial, the sequel The Judgement - most curiously embodied in Kafka’s story by this title. And the unexplained entity, edifice, bureaucracy, individual life in The Judgement are in some ways more remarkable and elusive that the labyrinthine offices in The Trial or the stern knot of puzzled society clustering about The Castle. In The Judgement an eerie lacuna is crystallized in the “friend” in Russia, who has set up business and been partially lost sight of by his former intimate. And – like du Maurier’s Rebecca – this figure exerts an influence beyond this world; in The Judgement, from a limbo in which even the existence of this person is gradually in doubt. He is, rather than a person, an urgent grotesque power which brings to the fore the inner landscape of relations between father and son and, at last, the Judgement itself that seems to bring in the meaningless noise and bustle of the city. When the “friend” is invited from Russia to the approaching wedding of his old intimate – invited, apparently, from a situation of hardship and failure in Russia – it must be wondered, who or what is being invited? In Kafka’s works, horror is of the piteous depth of Metamorphosis and the fate of the sapped and weary K. of The Trial, predominantly. But the nearest to a pure horror story of spiritual possession is, perhaps, The Judgement.

Kafka brushes themes of horror and the supernatural and science fiction in many surreal and unexpected ways. The point of “The Whipper” in The Trial, a chapter so un-Kafkaesque in its explicit in-your-face-fantasy element, is that it is an emblem of the whole work, although uncharacteristic of it.

But the heart of The Trial – and perhaps the heart of Kafka as a unique creative artist – is Chapter VII, in which the painter asks Joseph K:

“Are you innocent?”

And yet, as Frau Grubach finds, both question and answer are abstract – she has the feeling of “something I don’t understand, but which I don’t need to understand either.”

In regard to such a wistful resignation

as this, I do wonder if Philip K. Dick ever read Kafka...

I came to this writer, in English translation, in my teens, and I will never forget the impact he had on me, but the impact then was from the three great novels, The Castle, The Trial, and America – the short stories, at that time, moved me not at all. But much later, coming back to Kafka, I attempted to read the novels and the stories in different ways. It is true that, in some examples, they touch – The Great Wall of China is a story much closer to the novels than it is to the great majority of the more stylized “shorts”, whereas America is a novel much closer to this very stylization. However, I do think there was a shift in artistic – it might be philosophic – intention between the novels and the stories, by which I mean that the author found each medium apt towards different modes. The one, that of the novels, contemplative, and the other, that of the stories, violent assertions of angst.

In the Description of a Struggle we see Kafka’s co-extensive significances, e.g., “I looked at him sadly – the piece of fruitcake which I had in my mouth did not taste particularly good.” However, Kafka’s “co-extensivity” can stretch over whole pages, chapters, stories. Mood is often engendered by anomalously unsynchronized movements, such as, in the same story: “I couldn’t understand why I was incapable of keeping step with my acquaintance – especially since the air was clear and I could see his legs quite plainly.” The impulsion, a dreamlike motive to further a conundrum on, comes again in this story when the narrator says of the young party-goer as they both walk in the snow: “Who knows, this man... might be capable of bestowing on me in the eyes of the world a value without my having to work for it... after all, when the girls kiss him, they also kiss me a little – with the corners of their mouths, so to speak...”

In The Castle, more than any other of the works, we see Kafka’s floating worlds of expression, in certain ways irrelevant to the main theme but in other ways expansively enlightening the theme.

For example, at the end of Chapter 7, the appearance of the Maids, during the meeting between K., Frieda, and the teacher:

"You’re surely in a hurry,” said K., who this time was very pleased with

the Maids; “had you to push your way in while we’re still here?” They did not answer, only twisted their

bundles in embarrassment, from which K. saw the well-known filthy rags

projecting. “So you’ve never washed your

things yet,” said K.. It was not said

maliciously, but actually with a certain indulgence. They noticed it, opened their hard mouths in

concert, showed their beautiful animal-like teeth and laughed noiselessly...

These floating irrelevant “enlightenings” in The Trial and The Castle are often in the form of grotesqueries – but in the short works, such grotesqueries embody the themes, they are the story, such as The Drunken Man, Description of a Struggle, and most famously of all Metamorphosis.

The forward narrative of The Castle comes like panic-pulsations of scenes, such as the first – at the first inn – with the bed of straw and Schwarzer of the Castle and his preliminary investigation of K.; then the scene with the house from which the door was “the first door that had opened during the whole length of the village.” The putting out of a plank from the door to rescue K. from the snow, in physical terms is a cord linking one scene to the next, and this effect of a tenuous but inevitable link is kept subliminally throughout. Then the scene at the second inn, the Herrenhof, where Klamm is staying, and where K. meets Frieda. And from here, most of the “panic-pulsations” commence to revolve around Klamm, such as the scene where K. enters Klamm’s carriage in the courtyard, and the episode at the school where even little Hans, the child of the vague-eyed mother at Lasemann’s house, seems linked to Klamm and to the Castle.

The injustice done to Amalia by the mysterious establishment of that edifice in the person of Sortini, is perceived by K. as the very image of the “fallen” girl – despised alike by the village and Castle; this image is beautifully displayed in the scene where Amalia is looking after her parents. Her sister, Olga, is ambivalent and ambivalence is of course a feature of the novel as a whole, which is to say, value and quality elusively exist in ranges of experience that cannot be pinpointed despite the hard focus. Is Olga right, that Amalia could have “wangled” things somehow, and so let her family off the “curse” which subsequently fell upon them from the Castle? The result of the curse is a sculpturesque and transcending image of Amalia – transcending Castle and village: a concept beyond. How many such concepts are there in Kafka, of such a “beyond”, such a release? They are not easy to spot, but once assimilated, have a curiously devastating effect, because of the very reason that they are camouflaged by the intense murk and exclusiveness of the style. C. S. Lewis suggests that such a style makes it unnecessary for the book to be “read” so long as the myth is “told” and that it is in the region of mythmaker that a genius such as Kafka lives and breathes. I think however that this is to miss the point about the style as, too, Erich Heller misses the point in his reduction of The Castle to an enveloping despair. The myth is reality and drabness that is made vivid and so, paradoxically, undrab, which is the quality and journey of experience. Thus the Kafkaesque Drab/Myth/Camouflage imagery becomes like a pantheon in the fog, with muted irony and dreamlike mis-match of style and consequence.

“The relation existing between the women and the officials, believe me, is very difficult, or rather very easy to determine.” Thus says Olga in The Castle. And such casual throw-away contradictoriness becomes the very texture and fabric of the world of Franz Kafka.

The father of Olga and Amalia, his slow martyrdom, the complexity of this in terms of his relations with the Castle and the village and his family – are in a sense a microcosm of K.’s experience throughout the novel: psychological-domestic with the fantasy-Castle looming over, world within a world, a world rejected by a world, and finally with only puzzled and puzzling glances left from some formless nightmare. The imponderability – the intangibility of personal experience is overshadowed by something vast and unknowable.

“(Father) wasn’t complaining about his poverty, he could easily make up again for all he had lost, that didn’t matter if only he were forgiven. But what was there to forgive? ...no accusation had come in against him...” p.199.

With the petitioning (p.202) the officials of the Castle and the petitioner dissolve into the bewildering fabric of experience with never a fixed point.

But (p.204) this abstract is claimed after all by the empiric-sensual, that is by the rheumatism and the emotions of the mother, such truth “Slipping through the incomparable sieve . . .” p. 251.

The third great novel, America, moves in the direction of SF, away from the suggested supernaturalism of The Castle and The Trial. The clear outlines of the ship are followed by the extraordinary clarity of Uncle Jacob’s steel house. And yet, as Edwin Muir says in his introduction to the novel, the essential Kafka, the “obstinate strangeness which is his sense of the ambiguity of everything”, is still there. The steel house, for instance, is completely invisible from within and Karl’s experience of the house is like a dream. Uncle Jacob’s desk, the bath, the furniture-lift and so on, take mythic forms. After the traumatic relationship with the Stoker, the last lingering touch, the experience of a suffering doomed man, it is as though Karl is set loose on a river upon a strange world.

The portentous relay of characters – the way one leads to another, in the unpredictable progression of Karl’s destiny – is a quintessentially Kafkaesque pattern, brought to stunning form in America: the passing of the Stoker and the ascendancy of Uncle Jacob; the passing of Uncle Jacob and the ascendancy of Pollunder – fraught with that eerie, wistful, doom-laden quality which is Kafka’s unique artistry, as though everything and everyone, after all, has merely stood still. Happiness, success, above all Belonging, might depend on merely a word, a transaction, a misunderstanding, or perhaps an imagined insult.

America, thought of by some as the slightest of Kafka’s novels, in fact contains many Castles and many Trials. The ship, the city-mansion, Pollunder’s country-house are self-contained worlds with their own laws, their own elusive raison-d’etre. And the Trial of the Stoker foreshadows the Trial of Karl in Chapter 6 of America. The supremacy of Mr Green is impersonal, juxtaposed with the feebleness of Mr Pollunder, who is expressed in physical detail and thus personalized. But it is Mr Green who is the stronger, and the more dominant force upon Karl.

The curious elusive pitch that is struck by Kafka, that lies somewhere amidst slapstick, narrative adventure, stream of consciousness, can be tantalizingly sensed in Chapter 4 of America. Here the rakish Robinson and Delemarche remind me very much of the two Assistants in The Castle. The buffoonery in America, however, strikes a more sinister note, with all the encroaching influence of Robinson and Delemarche over Karl’s life and possessions. But the characters of Therese and her mother read as something of a paean – the mother’s tragic climb and fall is the most beautiful example of an attempt to escape out of the Kafkaesque world itself, a reaching to beyond.

And thus, full circle! For the Trial is everywhere, the Trial is the cosmos itself; the Trial is all through the extraordinary Diaries of Kafka and his Letters to Felice.

Perhaps after all there is a way out if only we could read the intimations, the signs in Kafka’s world, if only the shrouded paths that glimmer become visible so that we can be led to that elusive concept of escape, perceived as dream-walkers perceive such truths, opaquely, if only we could strike a sure path as Joseph K., as Karl, as K., as Kafka tried to do. But it is probably as Emily Dickinson – Kafkaesque in her own sublime way – saw it:

It might be lonelier

Without the

Loneliness –

I’m so accustomed to

my Fate –

Perhaps the Other –

Peace –

Would interrupt the

Dark -

And, crucially, this poem ends with –

It might be easier

To fail – with Land

in Sight –

Than gain – my Blue

Peninsular –

To perish – of

Delight -

Emily Dickinson, Poems # 405.

I wonder . . .