Mimas

The wonderful Chesley Bonestell picture, which you can also find on the What to see on Mimas page, needs to be shown here as well, because of the central issue it raises.

Saturn from Mimas (1944) by Chesley Bonestell (1888-1986)

Saturn from Mimas (1944) by Chesley Bonestell (1888-1986)Stid: It's an awesome piece of art, but so peaceful that I can't see any "issues": certainly a lifeless scene, but its very starkness is part of its beautiful realism. Even the keenest OSS fan surely would not wish it cluttered with Mimantean creatures; and the tiny spacesuited figures, which you can just make out near the left side and in the middle, add rather than subtract from the magnificent loneliness.

Zendexor: Ah, but something else also is absent, and that's what I'm celebrating: NO CRATERS!

Stid: You don't like craters, then.

Zendexor: I don't mind lunar craters; they're old pals of my imagination, part of our satellite's identity. Nevertheless, with regard to smaller worlds in general, the theme is overdone. It took me a while to develop craterophobia, but today as I write in grumpy-old-man mode [11th January 2025], instead of going on about the younger generation, moral decline, social decay and late postal deliveries, I choose to target the plaguey pock-marked topological tedium of ubiquitous rock-bowls!

Stid: Calm down, Z. Craters aren't actually ubiquitous. Even on the Moon -

Zendexor: Yes, yes, the Moon is actually endowed with a pleasing variety of terrain - not only craters but very respectable mountain ranges, rilles, domes, plains... Mercury however is a sad case, as is Callisto, and as for the small icy satellites of Saturn, including the real Mimas, they're pretty hopeless. Just look at this:

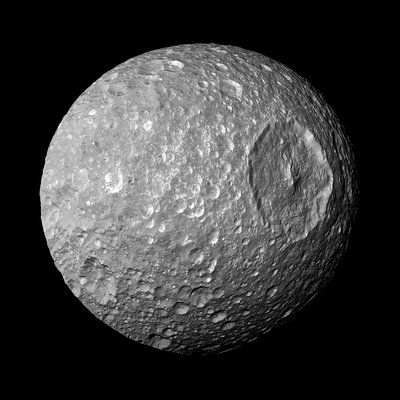

Mimas from Cassini

Mimas from CassiniHarlei: Maybe it's not as completely boring as all that; perhaps the giant crater Herschel so blatted the surface that some terrain inside the impact boundary shows more variety which we might see better if we could go there and look.

Zendexor: Thanks for that crumb of cheer, Harlei. Let's hope you're right. One can also hope that the process of cratering, if carried to a sufficient extreme, may create some interesting jumble that no longer looks like a strew of dishes. Or some impacts could cause interesting landforms to appear elsewhere on the impacted body, like the chaotic terrain antipodal to Mercury's Caloris basin (there, I've managed to say something positive about the real Mercury).

Stid: Seems to me you're wandering off the point. This website is about the Old Solar System and I want to hear about the profound OSS-related issues raised by the Bonestell painting.

Zendexor: Very well, but let me remind you that this website is about the OSS not merely in fiction but "in fiction, science and art", and though fiction predominates on most of the site's pages, it doesn't on this one, or at least not directly. After all, not many works exist from which I could quote fictional Mimantean scenes.

Stid: Granted, but all motivations for our interest must ultimately spring from the imagination...

Zendexor: Which brings me to draw an analogy.

Bonestell painted his picture in 1944. That's fairly close in time to Clarke's depiction of the Red Planet in The Sands of Mars (1951). In each case, though by different routes, we reach the numinous portrayal of a "charismatic" world.

In the Martian example of the 1951 novel, native life is important, life in a thin enough veneer to allow the harsh "bone" (as it were) of the planet to show through, and thus in an austere duet life accompanies non-life towards the borders of infinity. In the Mimantean example of the 1944 painting, exquisite rock formations glow in the planet-light and the sunlight, to adorn the scene in combination with the giant globe of Saturn lolling closely beyond the horizon, again bringing infinity close... What I'm trying to say is that both worlds are given to us swathed in a loneliness that glows like an aurora, a ravishing transparency "lit" from beyond.

Stid: And so the analogy is...

Zendexor: Shall we say, "less is more"? That is the nub of it. Smallness or paucity brings the infinite close, because on a small world you're closer to the horizon, and on a harsh world you're closer to the extinction of marginal life; both ways you whiff immensity sooner.

Stid: And all this came out of your liking for a landscape of crater-less rock!

Zendexor: Which in turn inspires another thought.

I wonder if a geologist might possibly be able to validate the Bonestell scene: that is, think up some processes for Mimas which could have resulted in the painting's craterless beauty existing for real.