Leigh Brackett and the old solar system

Full of narrative spice, blood and vigour, the Old Solar System of Leigh Brackett has achieved classic status.

world by world

[Note: this list is not exhaustive but merely reflects the extent of Zendexor's reading]

On Vulcan: Child of the Sun

On Mercury: The Demons of Darkside; Shannach - The Last

On Venus: The Vanishing Venusians;

The Moon that Vanished;

Enchantress of Venus

On Earth: The Citadel of Lost Ages (set in a future in which our planet has ceased to rotate).

On Mars: The Secret of Sinharat; People of the Talisman; The Sword of Rhiannon; Shadow over Mars (also titled The Nemesis from Terra);

The Last Days of Shandakor; The Beast-Jewel of Mars; The Road to Sinharat

For a rare sidelight on "moth-men of Phobos" see The Halfling.

On an asteroid: The Lake of the Gone-Forever

On Ganymede: The Dancing-Girl of Ganymede

On the tenth planet: The Jewel of Bas.

Brackett was one of the greatest sword-and-planet authors. Her work has a flavour all its own, but nevertheless invites comparison with that of Edgar Rice Burroughs.

Harlei: Comparison - and contrast.

a scruffier, darker mars

Zendexor: Yes. For example, both ERB and LB wrote swashbuckling romantic tales set on Mars, but whereas ERB's Barsoom is an arena for relatively clean conflict and excitement, the Brackett Mars (BrackM for short) is frequently sinister.

Whereas on Barsoom the old deserted cities are objects of melancholy beauty, and the more modern cities are fully alive, every single native city on BrackM seems for one reason or another to be crumbling and spooky, or rotten with some secret evil. Only the Earth colony and spaceport, Kahora, has a refurbished and functional feel to it.

There were many lights, far below. Tiny pinpricks of flame where torches burned in the streets beside the Low Canal - the thread of black water that was all that remained of a forgotten ocean.

Stark had never been here before. Now he looked at the city that sprawled down the slope under the low moons, and shivered, the primitive twitching of the nerves that an animal feels in the presence of death.

For the streets where the torches flared were only a tiny part of Valkis...

[The Secret of Sinharat, p.12]

Poverty, dirt, hardship and a picturesque (and picaresque) scruffiness are rife on BrackM, whereas on Barsoom you seem likely to live well if you can stay alive at all.

Harlei: In that connection, I can point out that thievery is unknown on Barsoom (John Carter says so, explicitly) whereas the cities of BrackM include a recognized Thieves' Quarter!

Zendexor: Well, there you are. And the environment is a lot less friendly, too. The dead sea-bottoms of BrackM are full of sand and dust, lacking the more pleasant ochre moss cover of Barsoom.

As they left the lights of Valkis behind, winding their way over the sand and the ribs of coral, dropping lower with every mile into the vast basin, it was hard to believe that there could be life anywhere on a world that could produce such cosmic desolation.

The little moons fled away, trailing their eerie shadows over rock formations tortured into impossible shapes by wind and water, peering into clefts that seemed to have no bottom, turning the sand white as bone. The iron stars blazed, so close that the wind seemed edged with their frosty light. And in all that endless space nothing moved, and the silence was so deep that the coughing howl of a sand-cat far away to the east made Stark jump with its loudness.

[The Secret of Sinharat, p.38-9]

The crossing of the desert in The Secret of Sinharat is a dire experience for the hero, Eric John Stark, an experience made more frightful because of his increasing suspicion that the woman he's with - the beautiful Berild, Queen of Shun - possesses a mind much older than it has any right to be.

On BrackM, threats often lurk covertly like this, compared with the more open challenges you find on Barsoom.

loners, outlaws and a moodier scene

Stid: Perhaps it's something to do with the absence of fliers on BrackM.

Harlei: How do you work that out?

Stid: Less ease of transport, more isolation, and as a consequence of that, more lost cities, lost civilizations and secret festering evils.

Zendexor: Don't forget, though, that on Barsoom you have the cities of Manatar and Horz, unknown to the rest... and Jahar hardly known.

Stid: Yes but it's not very credible, it goes against the grain for a world criss-crossed by fliers to allow the concealment of whole cities - whereas on BrackM, on which you have to ride on beast-back to get anywhere, you can more easily believe, for example, in Shandakor, or the non-humans beyond the "Gates of Death" north of Kushat in People of the Talisman. (I say "more easily", rather than "easily".)

And the point I'm trying to make from all this is that you can postulate a link between the isolation of cultures and the persistence of evils, and that explains why poor old Stark keeps shivering as he senses hidden horrors. Which in turn makes him moody and discontented, in contrast to the positive-minded protagonists of ERB's Barsoomian tales.

Zendexor: I accept what you say. Brackett is into loners in a way that ERB was not. This applies on others of her worlds - for example David Heath's Venusian quest in The Moon that Vanished, and the greed-driven Rand Conway in The Lake of the Gone-Forever.

Harlei: I reckon Brackett is closer to Robert E Howard in some ways, than to ERB, though it was ERB's The Gods of Mars that first influenced her and set her on the way to her own Mars stories.

In fact, anyone who regrets that Howard wrote no OSS stories (and no planetary adventures at all except Almuric) might (I strongly suggest) take comfort from reading Brackett. Her blood-and-thunder is sometimes as good as his. You'll have to look far before you can find a battle-scene to compare with the attack on Kushat in People of the Talisman. (For more on Kushat and on BrackM cities generally, click here.) ERB does good battles too, in The Gods of Mars and A Fighting Man of Mars especially, but the tone is not the same as Brackett's - ERB's is more hallucinatory, spellbinding like a dream is spellbinding, with the excitement of spilt blood but without its stink.

Stid: I didn't know you were like that, Harlei. I must watch my step...

colourful wickedness & picturesque evil

Zendexor: Which reminds me, to consider the morality of the stories.

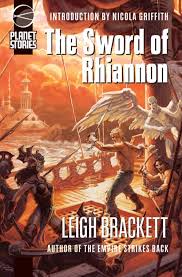

original title of The Sword of Rhiannon

original title of The Sword of RhiannonBoth ERB and Brackett bathe their writings in a kind of moral-acceptance field, a distorter force-field which slews the values of right and wrong - to the extent necessary for the narrative's particular colour.

For example, on Barsoom we have the bloodthirstiness of the main hero, and also his comic vaingloriousness - "You need not feel humiliated at your defeat; far better men than you have gone down before John Carter, Prince of Helium."

On BrackM we have what almost amounts to a re-classification of evil itself as a kind of colour on the stories' palette.

I have to put it this way, because the word "evil" is used so often, in a descriptive and atmospheric kind of context, that it almost loses its moral connection and becomes primarily a sense-impression. A flavour, almost. Here it is surfacing in Valkis:

Women looked at Stark. Women graceful as cats, bare to the waist, their skirts slit at the sides above the thigh, wearing no ornaments but the tiny golden bells that are the particular property of the Low-Canal towns, so that the air is always filled with their delicate, wanton chiming.

Valkis had a laughing, wicked soul. Stark had been in many places in his life, but never one before that beat with such a pulse of evil, incredibly ancient, but strong and gay.

[The Secret of Sinharat, p.14]

And here we have the wickedness of another city:

Jekkara was not sleeping despite the lateness of the hour. The Low Canal towns never sleep, for they lie outside the law and time means nothing to them. In Jekkara and Valkis and Barrakesh night is only a darker day.

Carse walked beside the still black waters in their ancient channel, cut in the dead sea-bottom. He watched the dry wind shake the torches that never went out and listened to the broken music of the harps that were never stilled. Lean lithe men and women passed him in the shadowy streets, silent as cats except for the chime and the whisper of the tiny bells the women wear, a sound as delicate as rain, distillate of all the sweet wickedness of the world.

They paid no attention to Carse, though despite his Martian dress he was obviously an Earthman and though an Earthman's life is usually less than the light of a snuffed candle along the Low Canals, Carse was one of them. The men of Jekkara and Valkis and Barrakesh are the aristocracy of thieves and they admire skill and respect knowledge and know a gentleman when they meet one.

[The Sword of Rhiannon, p.5]

And we accept all this, while we are immersed in the story. That's the acceptance-effect of the moral distorter field. (For the way the acceptance-effect works elsewhere, see the page on moral dimensions.)

Stid: The way you put it, it's enough to make one doubt whether one should read this stuff. I don't care, but -

Zendexor: But why don't you care? Answer: because I'm right. The distorter field works.

Stid: But - should it? Should we let it? I'm only considering it on your terms, understand. Not minding for myself.

Zendexor: It's important that it should work this way. It's right and proper. For since the stories enhance our lives, they needed to be written; and since they had to be written, they had to possess the distorter field - otherwise they would have been bad, for there would have been no translation from one mode to another: we would have had to approve of evil, bloodshed, etc, directly.

I used to have a variant of this sort of problem with the Zothique tales of Clark Ashton Smith. They were full of horror and evil, necromancy etc, but also very colourful. In the end I accepted the horror as just a colour, or flavour. And that was that. That's how it works.

Leigh Brackett, "The Beast-Jewel of Mars" (Planet Stories, Winter 1948); "Child of the Sun" (Planet Stories, Spring 1942); "The Citadel of Lost Ages" (Thrilling Wonder Stories, December 1950); "The Dancing-Girl of Ganymede" (Thrilling Wonder Stories, February 1950); "The Demons of Darkside" (Startling Stories, January 1941); "Enchantress of Venus" (Planet Stories, Fall 1949); "The Halfling" (Astonishing Stories, February 1943); "The Jewel of Bas" (Planet Stories, Spring 1944); "The Lake of the Gone-Forever" (Thrilling Wonder Stories, October 1949); "The Last Days of Shandakor" (Startling Stories, April 1952); "The Moon that Vanished" (Thrilling Wonder Stories, October 1948); People of the Talisman (1964); "The Road to Sinharat" (Amazing Stories, May 1963); The Secret of Sinharat (1964); Shadow over Mars (1951); "Shannach - The Last" (Planet Stories, November 1952); The Sword of Rhiannon (1953); "The Vanishing Venusians" (Planet Stories, Spring 1944); Edgar Rice Burroughs, The Gods of Mars (1913, 1918); A Fighting Man of Mars (1931); Robert E Howard, Almuric (serialised in Weird Tales, 1939)

For a suggestion that Brackett's extrasolar world Skaith could have fitted as a rendition of Titan, see the OSS Diary for 16th July 2016.

For the contrast between the Brackett Mars and Barsoom, regarding the location in time of Mars' Golden Age, and including quotation from The Last Days of Shandakor, see the Diary, 3rd November 2016.

The Last Days of Shandakor is discussed also in Mature Martians.

For Citadel of Lost Ages, about a non-rotating Earth, see the OSS Diary, 4th February 2017.

For Brackett's chronology, see the OSS Diary, 15th February 2017.

For a suggestion as to Martian history-writing, see the Diary, A Fun Sub-Sub-Genre.

For The Sword of Rhiannon see the Diary for 4th May 2017.

For The Halfling see Rich OSS Background for an Earth Tale.

For The Lake of the Gone Forever see Chill on beautiful Iskar!

and the additional note, How to borrow a fictional asteroid.

See also the extract, A snowy but habitable asteroid.

For some discussion leading to remarks which exonerate The Secret of Sinharat from a charge of relevantitis, see the Diary for 7th January 2018.

For Citadel of Lost Ships see Space Sargassoes, Derelicts and Clumps.

For a literary comparison see Leigh Brackett, Keith Laumer and cosmic tragedy.

See the Diary entry Brackett, Bradbury and "past-future" dates.

For The Halfling see The implicizer aimed at the moth men of Phobos.

Gazetteer: for Citadel of Lost Ages see New York City; for The Halfling see Los Angeles; for The Long Tomorrow see Canfield and Louisville.

Travel and its effect on Martian civilization in Brackett and Burroughs points out a sharp contrast.

More extracts: see - Hunted on Mercury - Sighting land on Venus -

Sinister encounter on Mars - A murky maze on Ganymede -

Trudging through the Martian desert - Industrial base on Pluto -

A sea-monster surfaces on Venus - A mysterious fortress city on Mars -

An ice-roofed city on Mars - Towards nightside of a no-longer-rotating Earth -

Fanged and flaming life and a castle on Vulcan.

› Leigh Brackett