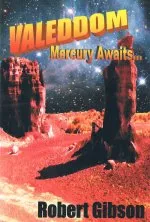

kroth: the drop

7: the plank

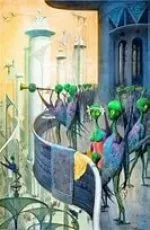

My disguise, hastily contrived, consisted of the crossed chest-bands of a “trusty”, a quisling, a slave who helped to herd other slaves. Mabglwa clumped along beside me. In front of us, in a line along the downward sloping branch, filed the other seven in our group of rebels: Vic, Cora, Elaine, Wulla, Dasnidd, Wherreth and Orlan – the entire contents of what I called “Rapannaf’s Ark”. Bringing up the rear, just behind Mabglwa and me, two faithful old retainers of Prince Rapannaf – brawny, simple-minded slaves whose names I did not know – followed us closely to ensure that the massive old woman did not stumble.

And that was it; that was our entire effort, our attempt at a diversion to help Rapannaf, wherever he was. I justified the operation to Mabglwa, in my most pompously expert tone: “Whether or not we succeed in our immediate objective; whether or not we survive; we shall inevitably be of assistance to him, if we engage the attention of the authorities, and force them to battle on two fronts.” I wondered, as I heard my own speech, how I managed to produce it, but Mabglwa did not retort, as she might well have done: “Yeah? Look at us, sneaking along, doing everything we can to avoid the attention of the authorities. Some diversion!”

If she had answered along those lines, I would have been forced to become more explicit, in order to focus her upon the idea that if only we could reach the Oracle Cavern we might then have the opportunity to sabotage our opponents’ power in a big way. I preferred to build up to this, rather than come right out and say what I intended us to do. Only if she had forced me, would I have had to show my hand.

Still she offered neither protest nor argument. Was she now hooked on helping us? Perhaps she was – she may have needed merely the one push that I had given her, the one crucial push towards the notion of revolt, and thenceforth she could be relied upon. Certainly she had done well by us so far, stretching her authority on our behalf. My impression was that it had been touch and go, even for her, the Moyt’s sister, to arrange this little expedition of ours, but she had quickly produced a ready-cooked story, and though the government forces now occupying Rapannaf’s palace had seemed perturbed when she declared her wish to remove certain prisoners to a different location, her glare was enough to swing it. Yes, it seemed she really was on our side.

And why not? Odious though she was, I had no reason to doubt her intelligence. If she really wanted to save her nephew it made sense for her to cast in her lot with us, no matter how much she hated and despised us, and now that she had made this move she ought to understand that there was no going back, or so insisted my chattery mind while my tongue waggled on with justifications. For me, also, there was no going back from the hypothesis which I sought to clamp onto us all.

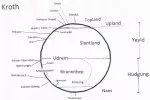

“It fits. All of it fits,” I said, “if we suppose that the Southern Hemisphere, the Underneath of Kroth, is inhabited. It used to be inhabited, for sure. People lived down there epochs ago. How they did it, we can no longer imagine. Proof, however, is present in the form of the empty seats which still occupy row on row of floor space in the Parliament building up in Savaluk; seats for the members from Hudgung, seats empty for ages. What happened to those people? What clings or glues to the upside-down lands now? Ask any slave in the Cavern and you’ll get the answer. The Slimes.”

I did not dare turn off the tap of my verbiage. The horror must be told, well told to motivate us all. Our beliefs must be engaged, our plans embraced, to work like Orpheus’ song that lulled the serpent which guarded the Golden Fleece. Here the “serpent” was the universe of unwelcome facts which coiled around us. It must be compelled to droop, to bow to my needs.

“It would be unreasonable to deny,” I lectured on, “that the Slimes must be the original, natural form of Hudgung life: evolved in an environment that favours only those creatures which can stick to a ceiling. Beings of that sort must possess the advantage over such as we, in a region so unnatural for human colonists, with sky below and ground above. Can we doubt that the men of the Southern Hemisphere, already contending with the fantastic difficulties of their physical situation, must have succumbed, must have been wiped out or enslaved by the biological horror? And now all the signs suggest that the Slimes, having repulsed the human incursion into their realm, are not satisfied with that victory. They have turned their attention to the North. Though not physically suited to Yeyld, though indeed possibly unable to pass the barrier of Udrem, they nevertheless appear determined to conquer by proxy.

“That is how we must read the influence of the Root. You see, my lady, you Gonomong are not your own masters.”

I saw her quiver a bit at this punch line. Amazing, how my whole presentation flowed. No doubt about it, I was in the grip of such inspiration, as to convince myself as well as my hearers.

“You have rituals,” I illustrated, “which enslave you to the will of the Slimes. I have seen some of you, with my own eyes, bury your heads in the Root. Yes, the Root is surely the conduit for commands that flow up from Hudgung. Now - those commands: what are they? Can we guess? Well, think about it: what must be the natural strategy for the Slimes to pursue?” Pause for effect. “Obvious answer: they must play upon your resentments of the North. An easy strategy because the facts of nature, the gravity gradient, in any case make it likely that you will hate the North. Fall-out from every northern disturbance, every northern accident and northern war, will always impact upon Udrem, literally in the shape of falling objects, for you are a dump for everything that tumbles or slips or slides down from anywhere upon the surface of Yeyld; you are the bin for the wastes of the northern hemisphere.”

I was really rubbing it in. Not only was I making sure that Mabglwa remained focused upon our aims, I was also speaking loudly enough for my words to be received by Cora, who walked in front of me and who, I guessed, needed to be convinced that what we were doing was a vindication of the idea which Rida died for: the idea that the Gonomong are not their own masters. It was, after all, just barely possible that we might meet up with Rapannaf again, and if we did, I wanted Cora to take the magnanimous view, that the triumph of truth was sufficient in itself; I did not want her quarrelling with the Prince, whom she held responsible for her lover’s death. So I spouted my theory in my effort to mnipulate my friends and enemies around on the chessboard of the emotions. My naiveté and conceit were awesome (I was aware of this at the time) but necessary – the wire upon which my stressed self had no choice but to walk.

“To reiterate,” I said, as crisply as a pair of slamming shutters, “your rancour towards the North makes sense – but,” and here I borrowed from the observations of the late Clem Harr, “your invasions of the North, your Rip-Migs, are pointless. Rapannaf clearly disliked them, and with good reason. They never settle anything. They bring you no advantage beyond the capture of a few extra slaves which you don’t really need. And you people couldn’t use the North even if you were to conquer it. You’d never want to settle Shoo Guneeng Gheeng. You’d miss the verticality, the jungle exercise for your arms; you’d run to flab, up North.”

An unfortunate remark, that, in view of Mabglwa’s own shape. I glanced at her, and was satisfied that she had failed to spot the insult, just as I had failed to spot that it was one. Her silence, dour and firm, persisted – implying, so it seemed to me, acceptance of all my ideas. I therefore took it as read that we agreed, that the natural resentment of South against North was insufficient to explain Gonomong belligerence; that a further cause must supply the answer, namely, the influence of the Slimes.

Mabglwa did occasionally open her mouth to grunt monosyllabic directions, whenever our aerial path forked. As for the rest of our company, their even greater quietness irked me. I stupidly longed, like a crowd-pleasing dictator, for the sound of voices uplifted in approval of my speech and my plan. Be realistic, I rebuked myself: don’t expect any applause; our disguise demands that we behave like a bunch of submissive prisoners under escort. The others are obliged to keep their voices low; too low for me to hear.

Ah, but on the subject of realism, what happens if someone gets to wonder why Mabglwa isn’t being conveyed in a sling-chair? Plodding doesn’t seem appropriate for the sister of the Moyt, does it? But there was no help for that. I would just have to hope that the truth remained un-guessed. Sling-bearers whom we might have used, who held special allegiance to Rapannaf, had gone off to join him; the only others available were ones whom his aunt dared not employ.

*

Our progress through the bottomless forest was unopposed, but laborious enough. It took hours, for it was not the direct route, and we halted many times while our corpulent leader rested herself. The rest of us got tired too, especially as we frequently had to clamber down awkwardly from one railed branch to another – except for Mabglwa who, on these occasions, was put into special harness and manoeuvred by her two henchmen. We were one hundred per cent exposed and vulnerable to any surprise attack. Fortunately the route we took was as disused as the stairway in a skyscraper.

The journey gave me time for second thoughts. I have had them so often that I have grown wise to them; many a time my second thoughts have turned out as futile and unproductive as my first thoughts, which gets me wondering sometimes whether the best thing might be not to think at all – but I found myself in an imaginary dialogue with Uncle Vic which was impossible to shut down. He was two places in front of me and I could not consult him, could not have risked a word even if he had been beside me, but that did not stop the conversation in my head.

“Uncle, we’re a war party without weapons.”

“Don’t exaggerate. Mabglwa has her pistol, and she packed her bag with knives and skewers from the kitchen. She’ll no doubt distribute them to us when we reach our destination.”

“Big deal. You know, I reckon I’ve blundered. I’m leading us into a trap.”

“Even if you are, it won’t be as bad a trap as the one you led us out of. Whatever happens henceforth, we’re all in your debt. Nothing could be worse than Unit 351.”

“That’s what I’m beginning to question –”

“You think too much. The time for thinking is past. Action is the point, now… as the fascists used to say.”

“That’s a dig, isn’t it?”

“It’s wrong to be fascist with other people, but one has sometimes got to be fascist with oneself. Otherwise one never gets anywhere. Especially if one is you.”

“I disagree…”

At long last we approached the vertical surface of Kroth, the cliff-face which I began to glimpse through the branches and leaves ahead of us. Mabglwa, still quiet, was walking like a machine. I no longer dared speak to her; my doubts were chokingly strong by this time. Just suppose, I said to myself, that Prince Rapannaf’s chances were not so slim as his aunt had made them out to be. Suppose her main preoccupation was not how to help him win, but something else.

Suppose, that she saw her contribution as to solve the problem of us.

We – her soft-hearted nephew’s “Ark” of Northerners. We, the nuisances whom he’d been unwisely protecting. What ought best to be done with us? Ah, that was the question!

If and when he won, we might become an even worse influence on him. We might get round to demanding general rights for slaves; we’d engross his attention, drag his reputation down...

Yes, we were her headache.

She could have swatted us like flies if it weren’t for Rapannaf’s own instructions, but now, now that clever clever Duncan Wemyss had himself requested we all be taken back to the Oracle Cavern, wasn’t this a priceless opportunity to get rid of us while at the same time obeying the letter of the Prince’s command to heed our wants?

All supposition. My heart should not sink so fast; not till the worst was confirmed should I despair, so I might as well wait and see. Here we were, about to pass the sentries, about to enter the cavern’s vestibule area. Be patient, Dunc, you’ll soon know! But my hopes had plummeted; Fate was a rogue, as I very well knew, so that the fact that we had got so far without mishap was absolutely no indication that the universe would continue to play ball.

In we went. The sentries saluted Mabglwa. No hitch occurred as we walked on through the narrow space towards the wider interior and the pillar-lights. Nobody challenged us in the gloom.

I could see no figures except five or six slaves who had knelt to the task of cleaning the walls. My mood swung again, towards possible triumph. The delicious thought came: perhaps I need only wait for co-operative events. Slaves might flock to us, like they did to Spartacus.

All right, Spartacus lost in the end, but he had a good run, and just imagine what he might have achieved if all his followers had obeyed him and he had had a single focus for his attack…

We slaves ceased to be strung out in a line, as by mute consent we moved towards each other, to gather into a close group, to confer, while mountainous Mabglwa hovered beside us.

“What now?” murmured Vic.

“Further in; a lot further in,” I urged. “Then we can’t miss it.”

Elaine said to the others, “He’s right.”

Thank you, wonderful girl, that’s just what I wanted to hear. I had a vivid, positive vision just then of what might lie mere minutes in the future. Knives and skewers, wielded by us, would stab into the Root whilst comrades recruited from multitudes of the other slaves would tackle the Cavern’s Gonomong with mould-scrapers and their bare hands, ambushing their enemies in the dimness, spreading the insurrection. Then to barricade the entrance... I opened my mouth to remark upon these great possibilities.

Instant blackness coated our eyeballs. The pillar-lights had flicked out.

Ah – could it have been that simple? A hand touched my side, tried to clutch; I heard a shot and the thud of a heavy body and the hand was withdrawn; none of us wanted to be the first to speak. We listened to each other’s rasps of breath. The shot was not repeated.

Still nobody spoke. To greet this somersault of our fortunes with any word whatsoever would have been unbearable just then.

We had not brought the means of making light, so in this pitch darkness we could do nothing. Had it really been as simple as that for our enemies? Yes, evidently. The truth of it sank my heart to the cave floor. All they had needed to do was flip a switch, turn the lights off to snuff out our rebellion.

What next, then?

I knew it before it happened.

Blinding rays hemmed us next. The sudden, horizontal beams smote us from every side, and while we stood with our eyes squeezed shut the torch-wielders came and put chains on us.

One mistake I did not make, while they clinked the chain round me: I managed not to say to myself, I told you so, told you she would betray us. My eyes opened long enough for one telling glimpse. In the brightness it was all I could endure, but it was enough to show me Mabglwa’s lifeless body, pistol fallen from her hand.

She had not betrayed us. On the contrary, she had been as surprised as we. But much luckier, in that she had had the means to avoid the consequences.

*

The torches dipped, the light became less severe and we were able to use our eyes; my interest in the scene was minimal, however, as we were marched back the way we had come.

In a store-room in the vestibule area our escort – about a dozen armed Gonomong – still without addressing a single word to us, man-handled us, and proceeded to envelop us in canvas coverings. Thus our vision was lost once more. Then we were lifted, carried like sacks of coal, and – so I sensed – brought outside again. I heard the creak of rickety frames. I pictured baskets and ropes. It became clear that I, and presumably my companions also, were being slung through the forest maze once more, in a downward direction.

It was reasonable to assume from our covered-up state that the authorities were not keen on the idea of a public execution. They did not need or want to make a dramatic example of us to the other slaves. They must prefer to get rid of us another way. I guessed it would not involve much of a wait, so the parade of possibilities would not crowd the thoroughfare of my mind for much longer – and gift of gab would be of no further use – and I, therefore, was through with speculation, dodges, cleverness. We had caused trouble enough; it would be unbelievably daft of the authorities not to make sure of us this time.

Consequently, under the advance constriction of impending death the range of my interest narrowed, and my one concern henceforth became the need to make a good end: to die with dignity and not to give way to cowardly panic. An achievement which would require all the guts and perspective I could muster. I could not afford any more moral blunders, not now that the path of my life had been bricked up short, the wall across my future looming near.

So, in the fond hope that my hateful cleverness had finally been stamped out, I quietly bade a secret goodbye to all my old ludicrous styles of self-belief. Goodbye, sharpness of wits! It was now time to transcend all that. And don’t even waste any feelings of shame on it all, I told myself. Rise far above self, or you will grovel at the finish.

On that note, I briefly empathised with the deceased Mabglwa. She, evidently, had shot herself rather than face the hideous shame of capture. From her point of view – poor wretched royal – anything was better than to live a moment longer as part of a failed slave-rebellion. That in turn gave me a clue as to why the rest of us had not been killed out of hand. I thought my way into the mind-set of the Gonomong leaders. They must be thinking: ‘Mabglwa had cheated justice, but her nephew must not be allowed to do the same.’ Rapannaf – whom they had perhaps already caught – would have to be punished fittingly... and what more fitting than to be doomed together with us?

I pictured the spaces being reserved for us to add to the humiliation of Prince Rapannaf. Yes, that was what we were -

Jumping to conclusions again, are you, Duncan Wemyss? Cleverly working it all out again, eh?

No, not this time. I had, at last, reformed. My ‘clever’ days were over because my days were over, full stop. No opportunity remained for any further brilliant insights of the kind that used to land me ever deeper in the soup.

Just maybe a hunch, that’s all...

*

The hunch turned out spot-on.

“Here are your friends, Prince!” – came the bitter cry to our ears, as we were dumped on some floor that resounded like a drum. They taunted him in English, perhaps with a phrase learned specially for the purpose.

Simultaneously my canvas covering was unzipped and I was tipped out of it. I blinked in a meagre dribble of light, in time to glimpse the similar emergence of my companions. They, like I, were shaken out of their wrappings into a grey, low-domed, circular space. Dazed, we lay or crouched on all fours. The bearers who had brought us to this place departed with quick strides that thudded and boomed.

I did not notice the means by which they exited. Nor did I see which of the Gonomong turned at the last minute to fling something in our direction, but I saw the small metal object glint as it turned over in its flight through the dim air – a key, thrown towards the centre of our space. A hand flew up and caught it.

The hand belonged to a shadowy form which heaved itself to its feet and then I heard the thud again, that boom of footsteps which accompanied any movement upon this floor-space.

Rapannaf it was, I saw as my eyes learned to adjust to a light that was pale and somehow odd, a light which made all of us look subtly different; as I tried to puzzle it out the Prince came and, wordlessly, unlocked our chains; as we shook ourselves free of them we murmured our thanks but his grim, weary expression did not encourage us to say more.

After he had loosed us all he stood back, and said, “They told me of your attempt. It failed even quicker than mine. You would have been better advised to stay where you were, but I thank you for your intentions. And now, since our last moments are all being watched, and overheard, I propose to say no more, but to enjoy the privacy of my own thoughts.”

Whereupon he went and sat back down in the dead centre of the resilient floor. Thud. Boom.

I had a go at standing upright; I managed it, although, because of the wide low dome, I cringed the way one does in a multi-storey car-park where the ceiling seems to press down more than it really does. I sat down again. Why did this floor tremble so? And what sort of light shone up through it? For that was why we all looked odd – I got it now – it was because we were lit from below.

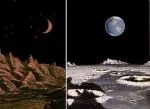

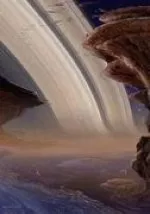

I bent to the floor and squinted closely, and I found that it was a fine mesh. I could see through it, and I saw – stars.

The heavens were below us.

We had been brought to the nether boundary of Udrem.

The stars, plus an accompanying sheet of fainter light, caused me to shiver with understanding. This room must hang from a branch (or some artificial branchlike structure) growing from the underside of the equatorial forest. The stars that shone in blackness half-filled the view of outer space below us; the other half of the underneath-sky was taken up with that strange sheet of light, several times as bright as the old Milky Way in the Earth universe. Awe thickened within me; almost enough to hold back the dread of my personal fate.

More thuds on the tense surface made me look up to see movement among us. I noticed Elaine go over to the Prince; their heads inclined together. Some of the folk whom I did not know so well formed a couple of whispering groups. Vic and Cora moved closer to me.

“Rapannaf’s right, about the lack of privacy,” said Vic in a low voice. “Audio pickups in the ceiling, and I think I can see spy-eyes, for what they are worth in this gloom. The government don’t want to miss anything.”

“The ghouls,” said Cora.

“Well,” said Vic, “they certainly won’t get any rise out of the Prince. He’s obviously going to stay quiet until the end comes, except maybe… hm, Elaine, brave girl, seems to have dared…”

“Dared to risk a princely snub, yes,” I said wryly. “She’ll be all right with him, I expect...”

Cora added, “As for me, I’m glad the government are listening to us. I can tell them what I think of them.”

“Good idea,” said Vic.

And yet Cora did not proceed to needle the unseen listeners. I guessed why not.

It would have been easy to jeer at the authorities because their purpose had failed: they had put us here as props, as embellishments of Rapannaf’s punishment, to humiliate the Prince, and yet he refused to appear humiliated; he had retreated into invulnerable calm. That was our moral victory, and it was obvious enough to need no emphasis. To taunt our executioners would be to detract from the dignity of our final hours, and might weaken the boundary between reserve and panic; I was on the right side of that boundary and I aimed to stay that way. Cora must feel the same. After all, what else did we have left but our dignity?

And that made me wonder whether dignity was also the reason that I heard no reproaches directed at me. I gazed at several kind faces, not only Vic and Cora but three or four of the others, as each of us fell silent in the gathering enormity of our thoughts. I could tell without further exchange of words that I still possessed the affection, loyalty and esteem of my friends and comrades despite the fact that I had got them into this terminal fix.

Well, apparently, they must have figured that the Drop was an improvement over Unit 351. My eyes drank in the reassurance of their regard. It strengthened me so that I was able to probe further. I stared past my companions, to the edge of the circle where the dome came down to meet the mesh floor.

I began to crawl in that direction.

I preferred not to stand, for the mesh yielded a bit like a trampoline, an unpleasant surface on which to walk. Besides, the domed ceiling soon got too low, as I approached the edge.

I looked back at the fellow prisoners whose doom I shared, and I noticed that they formed less of a huddle than before: both as individuals and as sub-groups they had spread further apart from each other. I nodded to myself. The suggestiveness that you get in certain dreams and which can force you to understand more than you wish, made me less mystified than I would have liked, by our unwillingness to concentrate weight on this floor.

A figure detached itself from its fellows and crawled out towards me.

I recognized him as Wherreth, a small wiry member of Rapannaf’s Ark.

Wherreth stopped a couple of yards from me and said in a low voice, “See them waiting? Behind the wall?”

My eyes followed the direction of his nod and I gradually discerned that the dome was translucent. I crawled right up to it. Yes, it was a mesh like the floor but with the holes a bit wider. I lay myself side-on to the edge and stared through it and quite easily saw a human shape, a head and shoulders, plus a block like a carpenter’s vice in front of the person’s chest. The block’s upper “jaw” was clamped on a part of the floor, and a release lever jutted out by the seated person’s hand.

Suggestive, all right. I squirmed backwards and crawled away from the sight. I had seen other waiting figures also – to either side – with their clamps, doubtless spaced all around the rim.

I asked my companion, “Waiting for what?”

“For dawn, of course.”

“I see.”

Execution by hanging, back in England in the days before abolition, had taken place at 8 o’clock. Had the Gonomong been influenced by the Dream of Earth? Or was death at dawn a natural idea? It could have been arrived at independently, on the assumption that the condemned should be allowed one last sunrise.

Wherreth sighed, “Here we are, at last, in the place one hears about so much. You know, the worst thing, I reckon, about the snamboffong, is its self-explanatory nature...”

I listened with half an ear as he mumbled on. I would have preferred, like the Prince, to be left alone with my thoughts. However there was one question I thought he might be able to help me with.

“How long have we got, do you think?”

“A few hours yet,” he shrugged, and then continued to witter on about the role of the snamboffong – the Special Plank – the Drop-point, in Udrem’s lore.

He had told me what I wanted to hear. It would be a few hours before the sun appeared. So we had some time before those levers were pulled. When they were pulled, releasing the floor beneath us, dropping us each into the great final Aloneness, it would be too late to talk any more. Before then, therefore, I wanted to have a last few words with Vic and Cora. But not straightaway. I had to sort myself out first... level out any hiding places where bad thoughts might have taken cover. I wanted my last words to be decent, my temper to be level.

Wherreth’s voice broke upon my ear. “If only we hadn’t...”

I stopped him right there. “We’re all meant to die,” I said, leaning over to plonk a too-firm hand on his shoulder. “And not only that, not only is everybody meant to die, but we’re all meant to die wastefully, unnecessarily.”

“How – how do you mean?”

“I mean,” I snapped, “life is as an experiment to test us to destruction.”

“Is that supposed to be a comfort?” he demanded in a tone of wonder.

“Yes, it is. You see,” I gabbled bitterly, “that’s why we end up against the barrier of the impossible. E.g. it’s impossible to escape from here, for the very good reason that we’re supposed to end up with something like this. Splat, like insects on a windscreen – so, accept it!”

Wherreth looked at my face in alarm. I realized I had raised my voice. Wrong approach – came the clear thought. This is no time to indulge in cosmic cynicism. Look at that fellow, he’s backing away.

“Sorry,” I sighed. “I had thought – had tried for better control than this.”

Had tried, yes, tried for control, and lo and behold, what spurts from my lips? A rant I hadn’t foreseen; right out of the blue... Hey, that was an unfortunate turn of phrase, for we were about to be dropped into the blue.

Wherreth was still backing away. I took a deep breath and admitted to myself that the time had come to face the hard physics of what was due to befall us. Up till this point my mind had shied away into generalities, life and death and dignity and responsibility and so on, and I hadn’t done so well, perhaps because I knew, deep down, that not for much longer would I be able to stave off the brute facts of speed and distance. Better to face them openly.

Once, in lower school, way back in my lost life on Earth, I learned from some article or chapter about parachutists that the human body in free fall attained a speed of about two hundred miles per hour before its acceleration was blunted by air resistance. I didn’t know whether the author was talking through his hat, but two hundred miles per hour seemed a plausible figure.

At that rate it should not take me more than a quarter of an hour to fall right through the atmospheric envelope of the world, to smash myself onto the crystalline ether that fills most of the space of this universe. A quick, merciful death. Except that – unfortunately – it could only happen that way if I were to fall from a young, new-formed world. Not from old Kroth. For aeons, loose matter had been falling from Kroth’s southern hemisphere, a stream of debris that had gradually eroded the polarized crystalline hardness beneath, hollowing out a long shaft, a deep pit of ordinary air down which we were condemned to fall for millions of miles, to join the perpetual rain of particles which became worlds’ debris-tales and were seen from far-off as the illuminated “beards of the stars”…

My neck bent, my head slumped, I gazed down through the mesh floor at the Nadiral Light and asked myself:

How long would it take? How long to plunge, say, one million miles, down that glowing “beard”?

Staring into the terrible loveliness of the light, I undertook the relevant calculation. Distance divided by speed equals time. A million divided by two hundred equals five thousand. Five thousand hours. In other words, slightly over two hundred days.

So, assuming that the air remained breathable, it would be thirst that would kill us at some point during that astronomical fall. Or perhaps the cold. Yes, the cold might act quicker. It would stay warm enough throughout the neighbourhood of the Sun, but once you’d fallen a few planetary diameters below near-Kroth space, well, according to the inverse square law you couldn’t expect the heat from the Kroth/Sun system to give much at that distance...

*

It turned out remarkably true, that it did me good to face these facts. The parameters of the Drop, once I’d managed to think through them – the practicalities of death by falling into the void – had a cleansing effect on my mind, for so profound were the figures for speed-distance-time that they wiped me free of petty cowardice and flooded me instead with an awed solemnity far superior to panicky funk. Would this relative calm see me through until the end? I was determined that it should. The enemy, Panic, must still be in the running, still striving to catch up, and I would be wise to make efforts to understand the temporary moral surge that had given my courage its lead, to ensure its prolongation and allow the numbers to continue to impress in such as way as to drive out the vagueness of terror.

On the other hand –

“Slippage, that’s the problem,” I muttered. “Slippage.” I listened to those words. What had dragged them up through my throat?

It was connected with religion. Aha, that was a bone that needed picking. Why wasn’t I getting comfort from religion? Or at any rate – not direct comfort.

Soul – body – life – death – afterlife – big words, true words, but it’s the embarkation that’s the problem. How to step across, without slipping, between “over here” and “over there”, how to believe that my self here will have anything much to do with my self there. How not to get lost in the yawning, unimaginable gap that separates two modes of reality!? How could any meaningful “me”, any actual identity survive such change? Here on the snamboffong I was prone to a kind of dread which I had not experienced before, not even in battle. “The slippage,” I muttered again.

A gentle fist nudged my shoulder. “Hey,” said my uncle. “You all right?”

I smiled at his inane question and said, “Er, yes, just like any normal bloke, I just split myself into two, so that I could hold a conversation with myself, you see.”

Vic grinned kindly, “You said something to that guy Wherreth that seemed to have impressed him.”

“Did it? I thought I’d alarmed him.”

“Well, that too.”

I reflected. “Must’ve been when I told him that Life tests us to destruction. I went on about it because I had to scotch what he was starting to say – his ‘if only’ stuff. ‘If only we hadn’t done’ (this or that). Madness lurks in the ‘if only’. I mean to say, regrets would drive us all nuts if we let them. Better just to admit that all roads lead to the Drop. Whether that’s the case literally, like it is for us here, or whether it’s just the lonely Drop of the last breath drawn in a bed in a nursing home; not really much difference, is there? – no way is there ever an escape.”

Vic nodded, satisfied with my conventional spiel, though I’m sure he knew as well as I did that there was a great deal of difference between the ordinary process of demise from old age and what we were soon due to experience. “Good point,” he said, by which I could tell that he meant “You’re wise to leave it there.” Death is death, it comes to us all, and that’s that. Having said that, he moved away a bit.

I muttered (very low indeed; I don’t think he heard it): “Well, if you think that’s an adequate reaction to The Drop, good luck to you...”

Some time later, I heard him, in turn, mutter some philosophical stuff, in line with his borderline agnostic beliefs, inclining towards some faint clutch at a larger hope, Tennyson-style. I listened while he put forward “the qualitative arguments for the existence of a transcendent truth”. Rather cold, cheerless stuff. “I admit,” he went on, “that if there is such a thing as transcendent truth, then it must touch us at every point.” Hey, that sounded a bit warmer. It turned out to be the best he could do.

As for me, why couldn’t I do better? I had the full apparatus of the Christian religion installed in my belief system and yet I still dangerously shivered at the second-by-second advance of the no-going-back. It wasn’t fear, it was the threat of fear, that set me the final security problem.

A random name came to mind all of a sudden.

Budapest. But what had the capital of Hungary to do with my mental security?

A city on a river. Two cities, originally. Buda on one side, Pesht on the other. In the course of time they grew together and fused, like London and Southwark, like countless other examples, but Budapest was a particularly good example in that the names of the two original components lived on in the compound name of the merged city, Buda-pesht.

A river can be a frontier, but what is a frontier?

A separation? Yes and no.

A frontier can pull, can attract settlement on facing sides –

Can abolish itself.

This applies also to the river of death. Charon the ferryman, plying his oar, is a developer. Life – Afterlife – fuses into Lifeafterlife, just as Buda – Pesht – fused into Budapest.

Suddenly the haunting nature of the Drop had become a possible comfort because the very fact that I could feel its shivery grandeur showed that I had already partly made the transition, I already had one foot in Charon’s boat, I’d smeared myself across the fuzzy boundary between life and death and the life beyond, it was already touching me and the embarkation was underway and, as for the inoculations you need to take before travelling to foreign parts, I needn’t flinch because I was being injected with otherworldliness now. The needle had already gone into me and it wasn’t so bad. We’re all partly ghosts already. We acquire that status the moment we realize that reality itself is haunted. And we realize that’s so as soon as we sense the transparency of the everyday. Good death begins early. It’s not a sudden thing. Part of growing up, in fact.

Out from my mental pipeline popped a ridiculous title I’d once spotted on the self-help shelves of a bookshop, “You Can Be Everything You Want To Be”, and with this dud recollection my mouth issued a moaning chuckle. Hey, I’ve just helped myself into the afterlife.

*

Rapannaf squatted in the lotus position, but the rest of us lay prone around him, to gaze down through the mesh floor as we watched the colour of the sky while the minutes and hours ticked by towards dawn.

The forest of Udrem above us must, I realized, act like a hat-brim to hide the Sun when it appeared. Nevertheless the brightening of the sky below us would give the game away, though it would be impossible to anticipate the exact moment of “dawn” for the execution.

Such a peacefully warm, companionable feeling developed between us during those last hours that we felt little need of words. I guessed that the others had achieved their own equivalent of my philosophic calm, and, like me, had managed to view our fate as a bridge to cross between two already-harmonised modes of being, rather than an abrupt Checkpoint Charlie between opposed regimes. Our eternal, immortal selves would prove to be an expansion of, instead of a contrast to, our everyday selves.

The Nadiral Light continued to shine in a beautiful swath below us, while the rest of the sky paled from black to grey...

A raucous scream, a spout of pure terror, blasted my eardrums and abruptly put in question all that courage of which I thought I’d had the title confirmed.

The voice shouted, “The Plank! We’re on The Plank!”

It was Dasnidd, a ginger-haired youth barely older than I. I had not guessed that he might crack; he had gone through the past few hours as well as any of us. Now he went to pieces. He flipped. He sprang to his feet and jumped, twice up and down, then lost his balance and sprawled on the mesh, while the rest of us were shaken about on the same quivering floor.

Embarrassed and in desperate sorrow, we did not know what to say to our broken comrade. We listened miserably while Dasnidd, crawling around us, gave vent to a sickening effort at hope:

“Look, how about escape? We’ve only got a bit of time to think of an escape. We must work something out. It must be possible. Look, this floor, they won’t want to jettison this floor totally. It would be a waste, wouldn’t it? They’ll want to keep it for re-use next time. So when the moment comes, not all of the clamps will be undone. One of them will stay fastened. The floor will open like a flap, like a bomb-flap in a plane, and if we’re alert we can hang onto it rather than fall... we could hang on to its lower edge, maybe, and then work our way up... something, something!”

It was pathetically horrible.

Prince Rapannaf was sufficiently put out to break his silence. “Even a slave,” he began, “ought to have better –”

Cora did not let him finish. Something inside her snapped, too, though her yell was one of fury rather than of fear as she blazed at Rapannaf: “You arrogant, Princely bastard! How dare you put yourself above us all? You shot Rida because he told you the truth, because you couldn’t stand being soiled, besmirched, by the truth he told you, you couldn’t take how he figured out you Mongee bastards for what you are, just puppets of the Slimes...”

Vic interrupted her, “Stop it, Cora, you’re going too far.” He said it with such unusual force – so unlike the urbane Vic Chandler we were used to hearing – that Cora instantly ceased her harangue. Vic went on, “We don’t actually know that Rida ever mentioned the Slimes. He merely said that the Gonomong couldn’t have acquired certain advanced capabilities by themselves. Such as the pillow universe treatment, for instance.”

This was a fair point, but not a central one, and before Cora could realize how she had been deflected, and refocus her wits to renew her attack, I decided to intervene.

I might have done nothing, might just have left Rapannaf to take any further tongue-lashing that might be coming to him. After all – why try to stop Cora from saying what she thought? But (so I reckoned) perhaps she had missed something. I suspected that the Prince had played a more expert psychological game that he was being given credit for. After all, his rebuke of Dasnidd had been effective. The lad had subsided. His frenzy was over. Maybe, a sharp telling-off had been the most merciful thing for him.

“Of course His Highness is arr-o-gant,” I smiled at Cora. “He’s arr-o-gating the right to make judgements because that’s his role, he sees it as his job – WOOOAAARGH!

The floor gave way beneath us. The time had come.

We rolled down the opening flap without the slightest chance to grab hold of anything – so much for Dasnidd’s pathetic idea. That was my last thought before all thought was torn from me, wiped away in the wind.

My mouth in the first moment stretched open wide to gasp at the scanty air that receded from it, and in the next moment my lips pressed shut again to shut out the cramming blast as I faced down into the smiting rush of air. Then in one more moment I was gasping again, and then choking the moment after that, over and over as I weightlessly tumbled, no more thoughts, just buffetings. I was a mere sensorium falling into the sky. My eyes could not bear the wind or the light. I squeezed my lids shut as I streaked out of the shadow of Udrem and into the full rays of the Sun. And the stark horror of weightlessness, which (for all I knew) might have been hard for me even if I had encountered it in civilized circumstances, was certainly a terror in the context of The Drop.

Weightlessness, however, did not last. As my acceleration slowed and came up against the limitation imposed by air resistance, I regained my sense of normal weight.

My body also learned to stabilize itself against the vertical gale, like some dopey half-asleep cat arranging itself on its cushion. That meant I could breathe more easily and now and then partly open my eyes, though they were not the eyes of understanding. My universe was the wail of the passing air and the prospect of the last long instant that stretched towards extinction.

>> 8: Hudgung