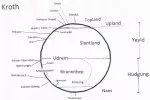

kroth: the slant

8: grass-skiing plunge

For three days we stayed in the pleasant town of Dorington Dradett, famous at the present time because it marks the current southward limit of the Road's construction. During those three days most of us, including myself, had to train intensively, to learn to ski on grass.

This would not have been necessary had my earlier speculations been anywhere near the truth. I confessed this to Bernie Prabbs as we slipped and slid and made fools of ourselves under the eye of a weary instructor, along with hundreds of other novices on a wide damp tilted meadow outside the town.

“My idea,” I panted, “was that the front line began where the Road ends. Stood to reason, I thought.”

“Brilliant. You were only eight hundred miles out – ouch!” He landed on his wrist. “Aaargh!”

“Idiot Prabbs!” yelled the instructor, bearing down on us. “You too, Wemyss – cut the chit-chat! Concentrate! The name of the game is – balance! And what are the rest of you krunkers laughing at? At this rate you'll be a lot of yemming old-age pensioners before you're any good! Put some effort into these few days, for heaven's sake, 'cause you won't get another chance in this flipping war, I can tell you!”

We concentrated. To my glad surprise, by the third day's practice I had become proficient, having graduated from a beginner's zig-zag to the more advanced style whereby you keep your hips pointed down-slope while you do the swerving with your knees – though I knew I couldn't expect this to work when the gradient became severe. I think most of us enjoyed acquiring the skills of grass-skiing; I know I did. The practical necessity was obvious enough: the Road had come to an end; those extra eight hundred to eight hundred and fifty miles South which still separated us from the enemy had to be traversed somehow, and for a great army in a hurry the only practical option was to ski. A bunch of tourists with time to spare might have made some use of the haphazard local “cable-routes” which, we were told, basically amounted to rope-controlled slides, but I never saw them and did not like the idea of them. I wanted no more careening about in vehicles of whatever sort. I relished, I craved, direct contact with the ground. To be thus “grounded” was the only way I could imagine myself enduring a descent of the world's flank without going mad.

In a crazy sort of way, part of me was even looking forward to it.

The day of departure dawned with a blustering wind as our company of about one hundred and fifty men took its turn to assemble in one of the meadows south of Dorington Dradett. When I turned my head for a last look at the town, my view of it was blocked by the enormous oblong warehouse that housed the stockpile from which we had been equipped – the last such supply dump on our route. From this point on, the army must fan out over countryside, quartering in scattered villages, encountering no more big buildings or roads or prepared sites for the rest of the journey. We were going to be “spread thin”. To make up for such diffusion, things were now more organized in a personal sense; I knew and recognized my superior officers, not only Captain Murena who faced us for inspection in these final minutes before our race to destiny, but also Colonel Reece who wished us luck as he passed through our ranks before disappearing into the next field to continue his review. I remember the Colonel's shiny buttons; how my imagination picked on them: “Relax! Things can't be that open-ended, if uniforms are this smart.” All sorts of illogical senses of belonging, and of subservience to timetables, helped counteract the prospect of being thrown into infinity. And on the meadow's southern boundary a curved line of chestnut trees, lashed by the wind, suggested a cordon of friendly gesticulating giants barring us from the gulf. I knew of similar tree-lines beyond, planted out in a fish-scale pattern extending for many miles. It was the stately remnant of a much denser, thornier zone of defensive vegetation dating from days long gone when this used to be the frontier. Nowadays the action was far to the south…. My attention veered back to the voice of our captain.

“Now – sticks down and move forward!” Murena was saying. “Next, you in the second line….”

I looked down once at my stubby grass-skis, flicked my eyes to right and left, timed my push to coincide with that of my neighbours – and we were off. This – was – it. Murena saw us move, saw us come towards him in reasonably good formation. Satisfied, he turned his back to us; his face no longer a white blob at the end of the field, he became a brightly coloured helmet to follow. We wove our way through the first belt of trees. Then we were in another sloping meadow with a similar boundary, through which another company was just then disappearing. We reached and passed through that next tree-line – and, to my surprise, halted.

When I saw the reason for the interruption, I laughed out loud; and I wasn't the only one. “No!” I heard someone say, “they can't be serious!” It was so obviously too late!

Old Tsorego, the gry pee, was holding a session in that field. Very clever, the authorities. I saw their game now. How it's played: always hold the griping session too early (like the one at Gheen), or, like this one, too late. Because, of course, when we are already setting off on our skis, we've psyched ourselves to advance and we don't want to have to rev up our courage all over again, don't want to voice complaints. Very clever it is, to give out the appearance of willingness to listen, without any danger of actually having to listen to anything substantial.

We were told we could break ranks; we were given an allowance of ten minutes for questions. Since none of us felt up to framing any questions, we mutely gathered round the wooden dais on which the gry pee stood surrounded by his jury – who had nothing to do on this occasion – and listened to Jon Tsorego.

The elderly conductor wasn't embarrassed at all by our silence; he invented gripes, to supply our deficiency. He voiced them and then he refuted them himself, in a manner which flaunted the self-confidence of the government. A weaker regime would not have dared the risk of putting ideas into our heads. The message was clear: Our trust in your loyalty and maturity is so complete, that we can afford to discuss the causes of this war in an objective, judicial spirit, considering all sides of the question, even while we are sending you out to fight…

“I have heard the view,” Tsorego was saying, “that the peoples of the South are bound to be oppressed; that we Northerners hog the best land, the nicest, lowest gradients, and that all our wars are therefore unjust. I have also heard the opposite view, that it is the peoples of the South who are the natural oppressors, because it's so easy to fight down-slope that, over centuries, waves of aggressive types move South and their habits take root there, while the meek – that's we Toplanders – stay North and enjoy our more gentle lives…. until times come, like now, when the bellicose Southerners turn envious eyes back in our direction…. If they recapture the North, the entire process may repeat itself over millennia, a kind of cyclic class-struggle. Remember that old nursery-rhyme about the two hemispheres of Kroth?

Yeyld doth Hudgung

Overlie;

Yet Hudgung conquereth

By and by….”

The words, to me, were just words, though around me I sensed some trembling at the rhyme's sweetly sinister lines. But then Tsorego continued the lecture in a kind of sub-Marxist sub-Darwinian style until we got bored and the ten minutes seemed too long. And that, of course, was the idea. I admired the entire skilled arrangement, and what was more, I came to the conclusion that it was all fair enough: designed, wisely, to show us that griping is always too late. The message: we're here not to complain about the idiocies and futilities of the campaign but to get on with it.

Fatalism gripped me as we set off once more; really set off, this time. All complaints on campaign boil down to one thing: the ultimate and only gripe: war itself, the sheer wastefulness of war. But then life itself from beginning to end is all one long squirt of waste. Nature is “by nature” inefficient, slapdash, incompetent to an appalling degree, matter and energy blown to the winds... This being so – on we go!

The last line of trees approached. This was a vital test. Beyond must stretch open country and the obviousness of the Slope, pointing us at twenty degrees down into the endless gulf. And now I would be skiing directly towards the sagging blue. The solemn ethical stuff about war and peace – how much had it diverted my attention? Distracted me, while a crust of stability formed over the molten terrors of vertigo? And when the crust got too brittle and thin, what then? Already, war and duty had become insufficient to prevent my thoughts spilling beyond them, and within seconds I was about to find out how far I had progressed in my ability to play good mind-saving tricks on myself.

The moment came, we were through the trees and click! I knew I'd got it. I had somehow taken on the posture of mind and body which could get me through another chunk of downward distance.

Take note – this is what you must do:

Hunched on your skis, being tilted yourself, you re-interpret the Slope as a level stretch with your movement as a magnetic pull along rather than a gravitational pull down. You can do this provided you refrain from looking too closely at trees and houses and anything else that is too plainly not at right angles to the ground. Of course it's just a trick. And the trouble with this kind of dodge is that you can't rely on it for long; sooner or later the cloak of protection it provides is snatched away by a sudden jolt of reality, and when that happens you'd better have a replacement ready to wrap round you, because it's rather late to search for your next illusion when you're thrashing about in panic.

In my case, the next “replacement dodge” turned out to be easy to find; in fact it could hardly even be called a trick, for it grew naturally prominent in my awareness. It was the great consolation of being on foot (skis count as footwear); of no longer being wheeled helplessly down-slope in some hurtling wheel or cart. No longer having to feel that I was being tipped into infinity without any control over my fate, now I was doing my own hurtling; I could stop if I wanted to – though if I did stop deliberately and without orders, I'd get into trouble. I suspected that some of the “accidental” falls I witnessed were of people who suffered an outbreak of fear and had to stop while they pulled themselves together. For me, it was enough that I could do the same if I had to. Enough that I could feel the steady ground underneath me, tilted though it was. Enough that I could exercise some vital degree of control in my direct contact with the world.

Beyond this particular reassurance, a larger comfort grew. The physical experience of days of continual skiing gave me a sense of the sheer solid bulk of the world. “All right, it slopes, but it's so huge it seems endless; and there is consolation in that.” With such illogical trust did my spirits lean on Kroth's massive planetary shoulder as I voyaged microscopically downwards, so that, on a journey which might otherwise have blown my mind, the simple size of it saved me.

Yet of course you can't fool the intellect all the time. Truth has a nasty habit of crouching in wait. The Slope isn't really an endless inclined plane, it's a downward curve; its gradient must increase in a trend from which there is no escape, the trend which makes a certain syllable increasingly taboo among all Krothan societies to be found along the route, until, after thousands of miles – supposing you somehow got that far – you would meet the vertical outrage denoted by that four-letter word, DROP….

I say, then, that the thought of the planet's comforting size is but a treacherous friend to one's peace of mind; its consolation false.

Consolation nonetheless, because the acceleration of tilt is slow, imperceptibly slow, to a skier. Its gradualness gave me a chance to acclimatize my Earth-oriented soul to the unthinkable that awaited me ahead.

Already in accomplishment I was far beyond what had been my capacity during the first days after I had awoken on Kroth. Back then, I could not have remotely imagined daring a ski run into the face of the south's gaping blue. My personal frontier was certainly advancing! What was I turning into? “A survivor,” answered my quiet inner voice. “Just another survivor.” Without realizing it at the time, I was preparing to acquire my version of the recipe for survival. My equally quiet companions, likewise, must have been concocting their own. None of us, so far as I know, had yet heard the term The Slant.

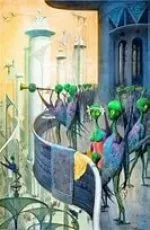

Now because we were on foot, and because we and the rest of the army were fanning out from the zero meridian path (which had been the Great Royal Road before Dorington Dradett; here it was just ‘the Wayline’), we learned a lot more about the country we went through. I noticed a tendency among my companions to heed those of us who were amateur naturalists and bird-watchers as they pointed out different species, and the slight changes in the colour of the grass we skied over, the turquoise tinge of the shellgrass, the richer and darker green of the shovelgrass… I noticed also that the grass became generally drier, more pleasant to sit upon when we stopped to rest or to camp out. The root system had to be more efficient and sophisticated the more we went south, retaining a higher proportion of the moisture that trickled down from the Pole. This increase in surface dryness might have made skiing more difficult, except that, of course, the effect was offset by its cause – the steepening gradient.

We appreciated the contentment we found in the populations of the villages and the little towns where we halted for our food and drink. They treated us generously, as well they might, since we were headed south to defend them. Even more important than this, they provided us with an example of successful adaptation. We chatted with them about their homes and their lives, and derived reassurance from how ordinary they were; all we had to be careful of – our officers warned us – was never to use the word drop, which was considered very bad language, more seriously bad the further one went South. I only boobed once, in this regard. A group of us, resting in a village, had been stood lunch by a charming old couple who were keen to support the war effort by showing kindness to soldiers. We were at a round table, in an idyllic outdoor restaurant. At the end of the meal we thanked them and I lightly said something about “dropping in to see you on our way back”. Silence fell. The villages winced. “We don't use that word,” said the gentleman.

“Oops. So we don't. Sorry, sorry.”

“Having said that,” said the lady, “we would like to add: do please d – r – o – p in on your way back!”

“Lisa, you're awful,” said her husband. “Now look what you've done,” he grinned at me. And so I was let off with a good-humoured warning.

In these village scenes, I often found it possible to narrow my sight and pretend I was looking at a street scene on a steep hill on Earth, though of course as the days passed, and we met more constant reminders of change, such cosy moments became rarer. From Latitude 65º onwards, that is to say after the Slope had increased to twenty-five degrees, we observed much more terracing than before, in the fields and gardens we passed. It meant more frequent interruptions of our ski runs, on the approach to each settlement, and we had to make more effort to seek the long stretches of common land where the Slope continued unimpeded. And of course as the gradient increased we had to zig-zag more widely with our skiing, so that the narrow runs ceased to be acceptable to us and we had to walk further across country to find a useable stretch.

I have mentioned “terracing”. Not all of it was artificial - in a larger sense. Imagine a hilly landscape on Earth, and then imagine it all tilted. It will then happen that the up-and-down hill-slopes will look more like steps. I mention this in case I have given the mistaken impression that we were always descending a smooth slope. The Slope had its corrugations, which would have been hills and valleys on Earth but which on Kroth seemed increasingly like a series of giant steps leading down – naturally, for while northern faces were tilted towards the horizontal, the southern were tilted away; tending towards ridges and scarps, respectively. All this applied in “hilly” country. Elsewhere the Slope was flat and smooth, and especially good for skiing; yet on average our progress South underwent a gradual deceleration as we had to pick our way with increasing care.

I must stress that this change was very gradual, hardly noticeable from one day to the next, though becoming obvious if you compared any one day with a week before. The slow-down was fortunate because after about three weeks of skiing, as the Slope approached a gradient of thirty degrees, my mental defences against the terror of the void were threatening to crumble. They had got me this far but they could not be expected to last much longer. It was as if I were dreaming on the edge of a precipice and an unwelcome hand were shaking me, an unwelcome voice saying, wake up you fool, look where you are.

Social pressures worked on me also. I become quite a regimental mascot, a butt of friendly jokes and of some that were not so friendly, though there was no actual bullying. Much in demand for my anecdotes of Earth, I seemed to have become a never-ending source of amused fascination on account of the vividness of my memories, which, to many of the men, made the old dream-planet seem almost real; but the tension in some quarters got channelled into a kind of envious contempt, either of me, or of the picture I evoked: Earth where the ground was always flat; Earth where life was soft.

Juldwin Ronth and Jason Kerallg were two who liked to tease me about Earth.

Juldwin Ronth was a “black” guy, that is to say, African in features though grey-skinned like all Krothans. French was his first language, but he also was fluent in English. I met him through his sister Aswen, who was one of the nurses on the expedition; I had asked her if she knew where I could find Elaine Swinton, and though she hadn't been able to give me any information, the sweet-natured girl not only promised to let me know if she found out anything, but also invited me to dine with her and her brother. His pal Jason Kerallg, a ginger-haired “white”, was a self-confessed Wild West buff; which is to say, his hobby was that particular aspect of the dream of Earth. Kerallg and Ronth more than once dragged me into their arguments about Earth history. At first I responded with approval of their thirst for knowledge, but their jokey indirectness, their frequent laughter, their habit of ignoring my opinion after having asked for it, put me off – even before I realized that they were using my ego as a punch-bag.

“Have another beer, negro!” suggested Kerallg to Ronth.

“It's my round, blanco!” offered Ronth. “Hey, Dunc, what do these words mean, anyway? I keep forgetting.”

Desperate things can happen in dreams, which would have no importance in the waking world, and vice versa. I wasn't up to explaining Earthly verbal taboos about race.

“I told you enough times,” I snapped. “Negro means black, blanco means white. They're just the Spanish words.”

“But why call people by different colours?”

“Because people do have different colours on Earth! Come on, you must remember that much! They're not all grey there!”

“Ah,” broke in Kerallg, “but there's more to it than that. Blanco never got used in English. Negro got used, then forbidden. Forbidden in English anyway. You had to say 'black', instead.”

“Really?” said Ronth. “The Spanish word is bad, the English word good?”

“Yep, I guess so. It's called political correctness. Isn't it, Dunc?”

I said sullenly, “We've been through this before. Historical pressures….”

“But what about the Spanish?” insisted Ronth. “I'm interested in the logic of this. What do politically correct Spanish people say? Are they not allowed to use their own world for 'black'?”

“Well, you got me there,” replied Kerallg, giving his head a solemn shake. “My guess – mind you, it's only a guess – is that the letters n-e-g-r-o must give off some evil vibration when spoken inside an English sentence but the vibration fails to get triggered if the accompanying words are in Spanish. What do you think of my theory, Duncan?”

“I think….” I relaxed my features. “I think both of you have succeeded quite well in establishing that the people of Earth were a pack of idiots. The topic is therefore exhausted, and we can proceed to talk about something else.”

“I might ask Captain Murena,” mused Ronth, “about whether there's such a thing as Spanish political correctness.”

“Don't blame me if you get shot,” remarked Kerallg. “That guy looks like General Santa Anna about to give the order to storm the Alamo….” From here, to my relief, the conversation took a new turn, diverted into whimsical physical comparisons between various famous people and our officers.

The next time they invited me for a drink, the eerie “where am I?” feeling nudged me in a big way. By this time we had journeyed so far south, we were actually in sight of the official boundary of Upland, or “Greater Topland”. That is to say, we were coming at last to the border beyond which the government's writ did not run. We sat in a tea-shop (that's what they called it, though it sold beer as well), in a village called Volost, latitude sixty degrees North. I could hardly refuse the invitation; Ronth's sister Aswen was still my best hope of finding Elaine.

“That's right, Dunc, sit with your back to the wall,” said Kerallg light-heartedly as I took my place at one of the tables. “You take your lesson from Hickok.”

“I take it,” said Ronth, “this Hickok personage was shot in the back?”

“Uh?” Kerallg gaped at the other's ignorance. “Sure was! Sat with his back to a door – the last mistake he ever made. Best-known fact ever came from South Dakota. Man, it's part of the general human racial subconscious by now…. Wassat, Dunc?”

“I said,” I said, “I just wondered if the Krothan Hickok met a similar end.”

“Aw, never mind about that. I don't suppose there ever was a Krothan Hickok of any importance. Say, you're looking a bit green, you know.”

In truth, queasiness had swamped my innards. It's not the door, my thoughts slurred; not anything to do with the door. It was the window that was at my back. And I wanted it to stay that way. Unlike the ill-fated Wild Bill Hickok I was likely most of all to be shot in the eyes. Shot by terror. If I turned my head.

Of course, I had already seen. Had already realized. Our company had been halted here in Volost for a couple of days now, waiting, presumably, for the leadership to decide which ski run to go for next. But to see a thing need not mean a lot. It's only when you can add the word “really”, that's to say when you really see it, when you really realize it, that the crumbling begins.

Searching for the next ski run? Rubbish. That couldn't be why the army was waiting here. At a Slope of thirty degrees it was time to admit that it was getting too steep for skiing. This was the end of the line for us Toplanders. This was where we were going to have to stand and fight. And this explained what I would see if I turned and looked out of the window; what I had once glimpsed weeks ago in the encyclopaedia back in that library in Savaluk.

The fortress of Neydio had affected me badly then, as a mere diagram on a page. It oppressed my awareness now, yet I won't say that I felt as horror-stricken, in sight-range of the real thing, as I did when it was just a picture. A silent revolution was taking place as I sat in that tea-room: some mighty wrenching process was going on inside me. The sick feeling was positive, a sign of something good. My mind needed to be churned, as a tin of paint can need a stir with a brush. Speedy re-arrangements of thought were accompanied by an understanding of the many good-byes I had heard during the past couple of days. Over a dozen members of my company, and similar numbers from other companies, had turned to plod back up-Slope. These departures signified that not everyone had been able to make The Adjustment. The Thirty-Degree Adjustment. The special slant you had to acquire if you were going to have what it took to live in these parts. For practice seemed to show that a Slope of thirty degrees was a kind of psychological turning point: the world now tipped so much, that there was a mass-extinction of those pretences and mental subterfuges which had kept us going so far. You gotta get the Slant, else it's no good. You adjust fundamentally, or you go back. And those who remain, such as I – what have we become? When next I stepped out the door, I might gaze unflinchingly down into the sagging blue sky, but would I look forward to crawling down the side of Kroth all the way to unspeakable Hudgung if need be?

“The line's gone dead. Hey, Dreamy, you all right?” came the voice of Juldwin Ronth.

“Sorry. Fine,” said I, straightening. A moment's effort was enough to bring me to a state of concentration and of clarity of mind. I actually felt good.

“We want your advice, man,” said Kerallg. “We hear you met the General.”

“Faraliew? I met him once,” I admitted.

“You know his tea-habit?” asked Ronth.

“No. His what habit?”

“Any one of us, any time, may get summoned socially. Along with the colonels and majors in his tent, we may find ourselves sipping tea and discussing strategy; yes, it happens, some poor sap like one of us gets chosen to attend, dragged into the conversation….”

“Socially, heck!” I snorted. “If he is doing that kind of sampling, it must be he's sounding us out, wanting to know how well the army will fight.”

“Well, then: suppose it is that. We still have to say something. Any ideas?”

Before I could think of an answer, Kerallg broke in: “Hey, how about this: we could tell him how eager we are, how much we're looking forward to battle; then he'll conclude we're mentally ill and send us home.”

I smiled, wondering how likely it was that his sort would remember stuff from Earth literature, or whether he had thought up Catch-22 independently. Either way, it was all right as a joke, but that was all. “It's maybe not so crazy, to want to stay and fight,” I suggested.

Ronth stared at me. “What? You – a fire-eater?”

“No, but think a moment. Are we really in such a hurry to start off for home? It's a long plod back.”

After a moment's silence the faces of the other two lit up, and, for once, they gave that kind of laugh which made me feel I'd struck just the right note. At that point we were interrupted – everyone in the room was interrupted – as the door was thrown open and an officer on the threshold shouted for quiet. “The Gonomong!” he cried. “The Gonomong Fingers have been sighted! All men under arms: report to your units – we are going to have to be ready to fight in a few hours. Locals: continue your normal activities, except when requested otherwise. That's all.” The officer disappeared. I and my companions shouldered our way out as the hubbub began.