clark ashton smith:

nihilistic transcendence

by

antolin Gibson

[ + links to: the Clark Ashton Smith page - The End of the Story (podcast) -

The Immortals of Mercury ]

In the Zothiquean story Xeethra there is spiritual desire embodying a life-quest. And this quest is in the context of an evil which, in Clark Ashton Smith’s stories of a dying Earth, is an expression of the intense pessimism that results from spiritual desire thwarted.

the doom of life

Evil, indeed – temptation, soul-damnation, despair.

And yet . . . not a low, but an empyrean-haunting pessimism, unlike that expressed by any other writer of fantasy! And this is a keynote of this extraordinary genius.

The whole of a life is in the shepherd boy Xeethra’s city of Shathair, in ancient Calyz: from purest wonder, to surfeit, to weariness and wistful longing to that which has passed one by. The city Shathair is a study of Reality, and the tentacles of deception – like the very powers of the demon Thasaidon himself – stretch from the elusive concept, to shape both the tale's beauty and its bleakest doom. Shathair has something of the melancholy of Charn in C.S. Lewis’s The Magician’s Nephew – the reminiscences of the Empress Jadis sound the same mournful harmony as the tale of Shathair’s plague.

But Xeethra, this most complex and haunting of the Zothiquean stories, is an epic of three phases – idealism, delusion, revelation – playing out the doom of Thasaidon’s bargain with the shepherd boy: a doom which, in Smith’s pessimistic philosophy, is that of life itself. The power of Xeethra and the other tales of Zothique and the other fantasy-cycles of this aurthor, is that their richness, starkness, beauty, and decadence so entirely suit this motif of pessimism and nihilism, and this motif is repeated from story to story in various and subtle degrees of intensity.

The Zothiquean Necromancy in Naat piles on Smith’s comical-cosmical horror-slapstick, but only to end in such deft and delicate poignancy, with the shadowy love of Yadar and Dalili. A question for the critic: if it had not been for the mock-solemn slapstick before the sublime love is described so beautifully, would such a poignancy in the ending be achieved? One cannot be without the other?

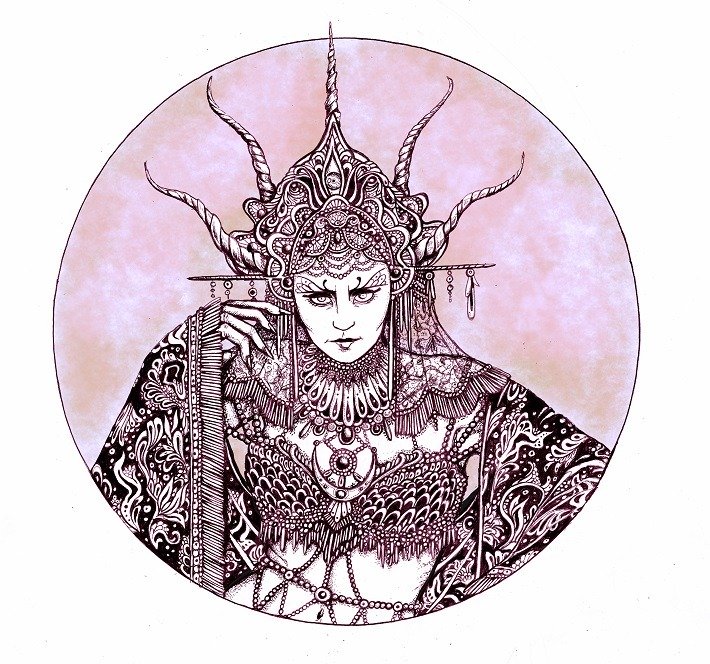

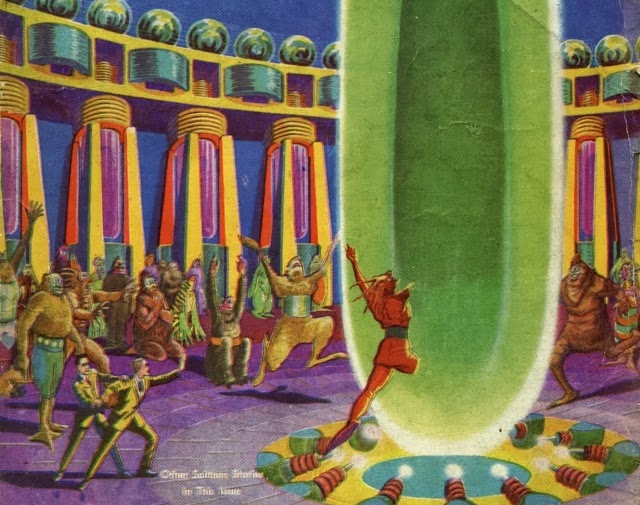

Ulua illustrated by Justine Jones

Ulua illustrated by Justine JonesThe most moralistic of the Zothiquean tales is The Witchcraft of Ulua in which, nonetheless, the gentle shyness of the humour pokes a little fun at the morality, but without seriously undermining it. The tale takes us to decadent Miraab, the capital of Tasuun, where Princess Ulua – the spoilt daughter of King Famorgh – receives a very satisfying come-uppance. The King’s senility and drunkenness seem the natural consequences of having such a daughter. The hermit Sabmon’s house on the northern border of the desert of Tasuun is a wonder indeed, swept daily with a besom of mummy’s hair (the best method). And, though Sabmon defeats Ulua’s witchcraft, and points the moral, yet he continues to study arts of enchantment and sorcery.

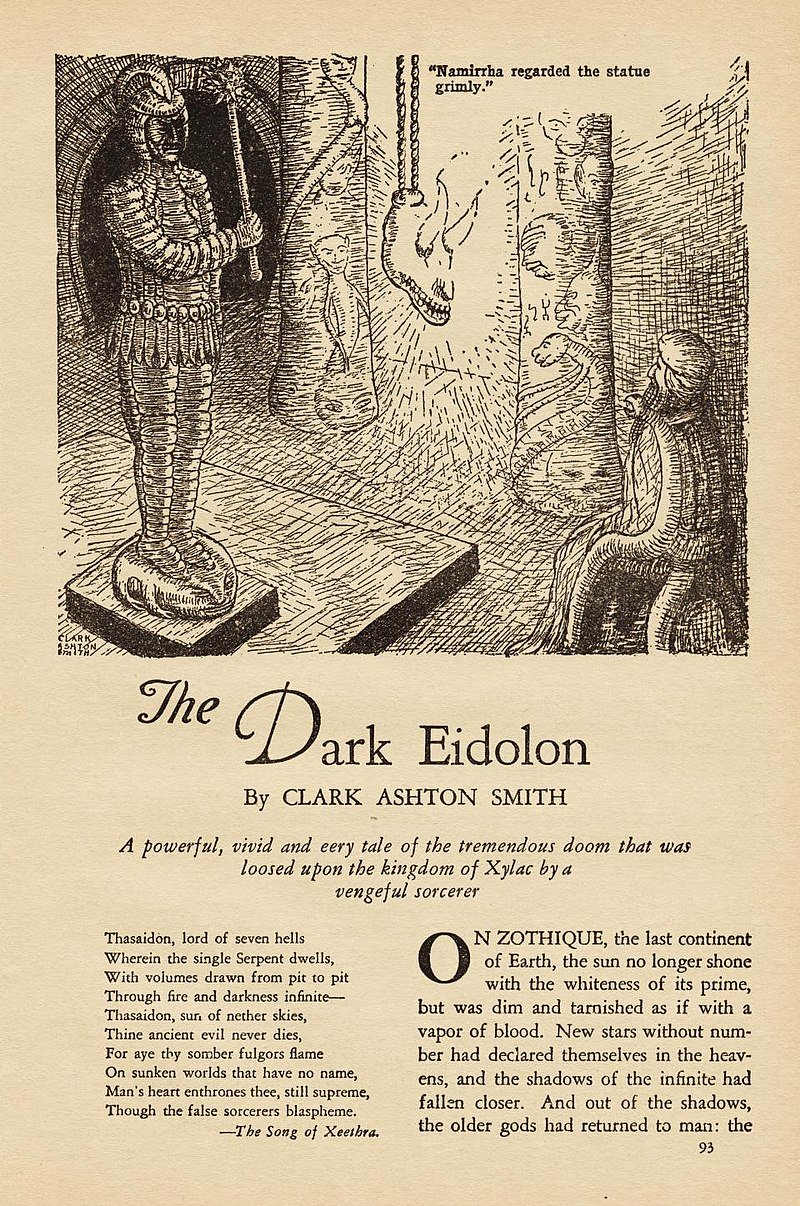

The Dark Eidolon is one of the most sumptuous of the Zothiquean tales, as well as one of the most subtle. As the narrative of vengeance gets under way, with Smith’s combination of sly dry humour and his rich gleanings of the vastness and otherness of magic, there are added cogent (and amusing) side-lights of the relationship between a despot (the Emperor of Xylac, Zotulla) and his people. For example, after the vengeful Magician, Namirrha, has conjured into being his tower in the palace-ground in the city of Ummaos, the locals “bragged a little of Namirrha and his dread thaumaturgies, even as they had boasted of the purple sins of Zotulla”. How fickle are the people! And when Zotulla declares that he must look to the “public good” when dealing with the Magician, the wryness of his sentiment can be felt, and even a sneaking sympathy for his “purple sins”. Zotulla lies “fathom deep” in his slumber from wine, but the sorceries of the Magician follow him into the deepest reaches of inebriation. Vengeance will run its course, and a version of justice will be done – but the Magician Namirrha will not escape either. He – who as the child Narthos had been crippled by the Prince Zotulla – had made his pact with the Arch Demon Thasaidon. And his conversation (which is exactly how the communication is presented) with the Demon, before the Dark Eidolon, points out the risk. For even the drunken Emperor, and his cowed but gossipy subjects, are useful votaries of the Demon, to whom the Magician’s lust for vengeance is a tiresome complication.

The pageant that takes Zotulla and his entourage, including the unpleasant leman Obexah, into the Magician’s tower, is a mesmerizing tour-de-force, and the outlinings of guilt in the form of the conjurings bring a weird psychedelic moral pattern and intent underlying the rites.

The story presents magic as, at once, delusional and devastating, chaotic and moralistic. To Nammirha the Magician, at last – his brain filled “with the shifting webs of delusion” – even vengeance, which he had cherished for a lifetime, is but an “obscure animus” which, nevertheless, still prompts him to his doom.

And remaining in Zothique for the time being, The Voyage of King Euvoran echoes Xeethra in the epic breadth and depth and combination of a haunting lushness and an unforgiving starkness.

The Master of the Crabs is one of Smith’s most richly imagined Zothiquean tales. This charts the journey of Mior Lumivix of Mirouane and his servant, and the theme is that of a treasure-hunt:

All our seacraft was required to make progress: for the wind strengthened wildly, as if swollen by the breath of devils. Above its howling we heard the surf’s clamor upon those monstrous rocks that rose bare and gaunt from cerements of foam.

This trembles on the very edge of a wild lonely poetry.

Of the Magician Sarcand and the treasure in the cavern of Iribos, the following glory manifests:

He dropped the huge hand that wore the signet of Basatan, plunging it into the chest behind him and bringing it forth filled with many-tinted gems, with pearls, opals, sapphires, bloodstones, diamonds, chatoyants. These he let dribble in a flashing rill from his fingers, as he resumed his peroration . . .

the power of illusion

But now let us step into our time-machine and go back – very far back – to Medieval Averoigne, a province in France full of old buildings which surely deserve a special grant of preservation from President Macron. These stories – which may appear as slight vignettes compared to the epic sweep of Zothique – are mainly concerned with the vampire-ridden woods, old towns and monasteries, which are are . . . well . . . quite charming.

But then realization creeps in that the nihilistic – and the picaresque – and the epic – are all present in Averoigne but to a subtly different degree, interweaving in different ways to those of Zothique, but still with the thrusts and sparklings redolent in all of Smith’s masterpieces.

Averoigne is full of surprises which, in true necromantic style, refuse to go with the flow. Take for instance The End of the Story. At first one settles down to the comforting formula, of a benighted traveller seeking refuge (in a monastery in this case) and having some forbidden secret revealed, thus being tempted, and drawn in, to some deeper and yet more mysterious circle of forbidden knowledge and experience.

But The End of the Story transcends such a formula (as indeed many “formulaic” stories by great writers do) because for one thing, there is the poetry of the prose, which has nothing of the Miltonic bombast of the Zothiquean tales. (I hasten to add that Milton is one of my favourite poets and that bombast has its place.) Rather, in Averoigne, there is a fresh, watery-jewelled, joyous creation as when the traveller awakes in the monastery the morning following his arrival:

When I awoke, a river of sunshine clear as molten gold was pouring through my window. The storm had wholly vanished, and no lightest tatter of cloud was visible anywhere in the pale-blue October heavens. I ran to the window and peered out on a world of autumnal forest and fields all a-sparkle with diamonds of rain . . .

Christophe Morand’s yielding to the temptation of the Lamia is doubly poignant, because the Abbot of Perignon, Hilaire, is hardly a repressive authoritarian figure. But Morand yearns for some fleeting truth:

. . . the vaguely hinted horrors of the monkish legend became imminently real in my imagination, and I paused before the black opening that was to engulf me, wondering if some Satanic spell had not drawn me hither to perils of unknown terror and inconceivable gravity.

Only for a few instants, however, did I hesitate. Then the sense of peril faded, the monkish horrors became a fantastic dream, and the charm of things unformulable, but ever closer at hand, always more readily attainable, tightened about me like the embrace of amorous arms. I lit my taper, I descended the stair . . .

The twist in the tale, and what gives it its philosophical and psychological depth, is the idea (touched on in the movie The Matrix) that the willing acceptance of illusion obtains to the greater profundity, than the mere adherence to a humdrum existence. So at the end of The End of the Story:

Soon I shall return, to visit again the ruins of the Chateau des Faussesflammes, and redescend into the vaults below the triangular flagstone. But, in spite of the nearness of Perigon to Faussesflammes, in spite of my esteem for the Abbot, my gratitude for his hospitality and my admiration for his incomparable library, I shall not care to revisit my friend Hilaire.

...and even harder reality

And now let us step into our time-machine once more and go back – yet farther back, from Medieval Averoigne, to the first of Smith’s Hyperborean stories, and this is a classic of its kind, having many striking similarities to M.R. James’s The Treasure of Abbot Thomas and to Jack Vance’s Liane the Wayfarer. Like these, Smith’s tale is one of treasure and of pursuit. And like many fantasy stories – passed over by those critics who are disdainful of the genre – it is actually for something. In just a few lines:

Far off and wan, a glimmering twilight grew among the trees – a fore-omening of the hidden morn. Wearier than the dead, and longing for any repose, any security, even that of some indiscernible tomb, we ran toward the light, and stumbled forth from the jungle upon a paven street among buildings of marble and granite.

- The Tale of Satampra Zeiros

And that desire, subliminal in daily reality and heightened in dreams, we have all felt, and is the heart and the purpose of this story. The succession of fortifying tipples which Zatampra Zeiros and his unfortunate companion, Tirouv Ompallios, indulge in – and which gives them such a misleading and light-headed confidence in their adventure – comes to an end, as the two thieves are pursued by one of the most terrifying creatures in all of the genre of fantasy and horror.

Travelling now to that Atlantean outpost, Poseidonis, we should really ask - has there ever been such a Magician’s room as that described in The Last Incantation? It is in this room of Malygris, who has been smitten by the great and eerie transcendence of cosmical pessimism Smith-style, that our eyes are, as it were, out on stems:

In his chair that was fashioned from the ivory of mastodons, inset with terrible cryptic runes of red tourmalines and azure crystals, he stared moodily through the one lozenge-shaped window of fulvous glass. His white eyebrows were contracted to a single line on the umber parchment of his face, and beneath them his eyes were cold and green as the ice of ancient floes; his beard, half white, half of black with glaucous gleams, fell nearly to his knees and hid many of the writhing serpentine characters inscribed in woven silver athwart the bosom of his violet robe. About him were scattered all the appurtenances of his art; the skulls of men and monsters; phials filled with black or amber liquids, whose sacrilegious use was known to none but himself; little drums of vulture skin, and crotali made from the bones and teeth of the cockodrill, used as an accompaniment to certain incantations. The mosaic floor was partly covered with the skins of enormous black and silver apes, and above the door there hung the head of a unicorn in which dwelt the familiar demon of Malygris, in the form of a coral viper with pale green belly and ashen mottlings. Books were piled everywhere: ancient volumes bound in serpent-skin, with Verdigris-eaten clasps, that held the frightful lore of Atlantis; the pentacles that have power upon the demons of the earth and the moon, the spells that transmute or disintegrate the elements; and runes from a lost language of Hyperborea, which, when uttered aloud, were more deadly than poison or more potent than any philtre.

What follows is the purest Poesque, and yet transmuted as though by one of Malygris’s philtres into the purest Clark Ashton Smith; the desperate love of the Magician for Nylissa which, retrospectively pure, now sinks into the cynicism and ennui of old age, is wonderfully and movingly conceived.

Curious indeed that Smith is such a master of the Love Story – bearing in mind too Necromancy in Naat – and perhaps it needs the misty trembly effects of melancholy fantasy, to capture the elusiveness of love?

up and over the border with science fiction

Clark Ashton Smith’s science-fiction tales of Captain Volmar and the spaceship Alcyone’s “voyage around the universe” are composed in a gothic style. To be frank, I do not believe these to be among Smith’s best, or the most typical of his genius – and the word really does apply to this writer – but the Gothic SF of Smith is funny, adventurous, and way-hey-hey, flying buttresses of words and ventures! There is a rooted yet happy-go-lucky quality reminiscent of Eric Frank Russell’s Men, Martians, and Machines. There are other SF tales too – such as The Vaults of Yoh Vombis – and this particular one, though set on Mars, could very well be translated to Zothique in the note of its horror and despair, having more than a little in common with The Weaver in the Vault.

However, on the disputed borderline between science-fiction and fantasy, is one of Smith’s very greatest tales - The City of the Singing Flame, perhaps the most elegiac and mysterious of all Smith’s works. It has echoes of Hodgson’s The House on the Borderland (which is also on that very disputed borderline between the two genres!) and makes of the city Ydmos an ideological apologia for all the stories of doomed desire and nihilistic transcendence that Smith composed. And yet, there is a final irony: the Singing Flame of Ydmos does not, as is first thought, snuff out the pilgrims like so many moths, but conducts them to the Inner Dimension, which is sustained by the Singing Flame:

. . . and those who fling themselves into the Flame are lifted thereby to this superior plane of vibration. For them, the Outer Worlds no longer exist. The nature of the Flame itself is not known, except that it is a fountain of pure energy springing from the central rock beneath Ydmos, and passing beyond mortal ken by virtue of its own ardency.

- The City of the Singing Flame, VI

And so the truth of Infinity can really and truly be grasped by the yearning of the poetic voyager – except that the positive irony has a twist! The Outer Lords, the Striding Doom, can snuff out Ydmos, which thus shall collapse upon the Singing Flame. And so the poetic voyager, his yearning thwarted but his physical life intact, scrambled back to earth.

The story is a miracle of description; of the human phases of fear, exaltation, and despair.

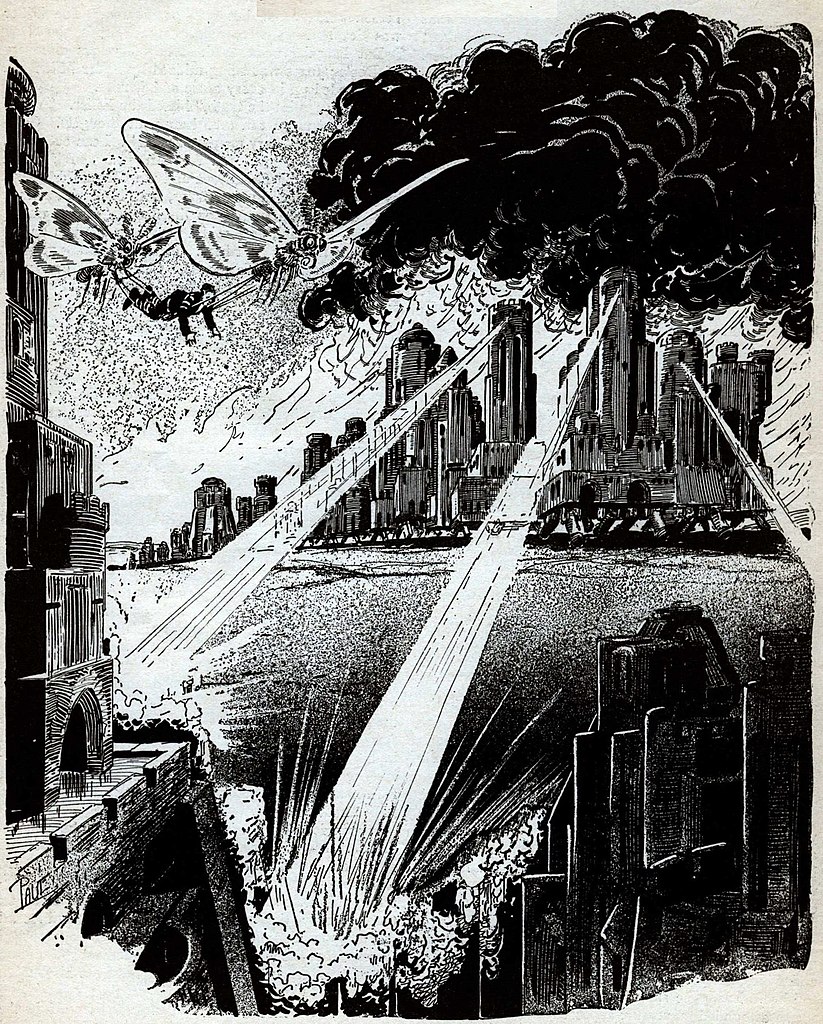

the Striding Doom bears down upon Ydmos

the Striding Doom bears down upon YdmosOne of the other great “solitaries” among Smith’s works – not belonging to any of the story-cycles – is The Devotee of Evil (not quite a “solitary” as the narrator, Philip Hastane, appears in The City of the Singing Flame and others, but he is rather a background figure). Devotee travels some of the territory of Doctor Jekyll and Mr Hyde and, indeed, the great anti-hero, Averaud, in Smith’s tale has motives perhaps not dissimilar to Jekyll’s, though wrapped in more metaphysical garb. But the Byronic character of Averaud aside, it is the idea in this story, and how it is communicated through the exuberant setting and paraphernalia of the experiment, that make it such a remarkable work: the postulation of a “monistic evil” out in space which, in a Hesiodic litany, is the source of all “death, deterioration, imperfection, pain, sorrow, madness and disease . . .”

Faust-like, Averaud must pursue his quest, come what may, and Hastane fulfils the role which, for the reader, is curiously comforting and therapeutic – that of the concerned and intrigued bystander who can do nothing to avert a tragic end.

The verve of the tale approaches the cinematic – the camera sweeps ebulliently from side to side, and the score hammers out a music of the darkest and most mysterious spheres – reminding me of the old Universal horror-film climax, such as in The Bride of Frankenstein, but still more indeed the creation of the robot in Metropolis, from the great UFA studio in Germany, which perhaps was the only film-studio that could ever have done justice to Smith’s fantasies.

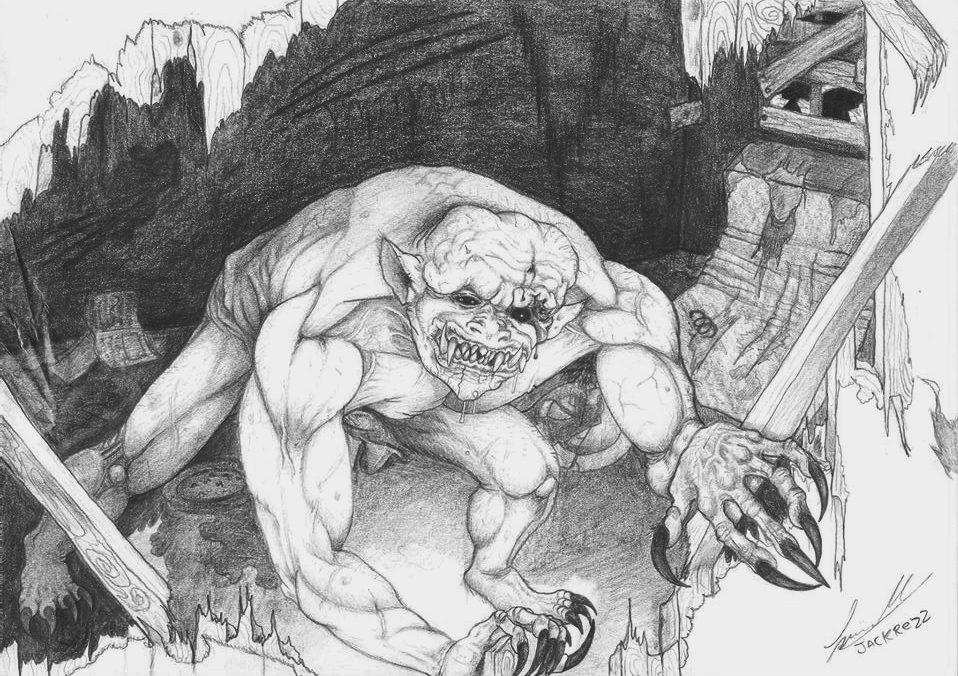

not a credit to the family

not a credit to the familyAnother story not belonging to the main cycles, and Smith’s best in the Poesque vein, is The Nameless Offspring – more akin to Poe’s The Fall of the House of Usher than to Lovecraft’s The Case of Charles Dexter Ward although the quotation from the “Necronomicon” preluding Smith’s tale formally places it within the Cthulhu Mythos, and the quotation seems pure Lovecraftian in concept. The elements in the story that recall Poe, however, are the stronger, and not least the agony and the melancholy of Sir John Tremoth, and the settled decline and despair of Tremoth Hall. Lovecraft’s excitable nihilism has no place in Tremoth Hall. But the concept of a boundless squirming reality of horror linked to our dimension by hidden passage-ways belongs to Cthulhu, and Smith nods his recognition – albeit a little tongue-in-cheek. For it is the poetic sensibility that interests Smith, rather than the concept.

To continue with the “solitaries”, the story Genius Loci – in addition to three extremely accomplished character-portrayals – is noteworthy because it nudges the crucial question that haunts SF and Fantasy: is it possible to give intrinsic “creaturely” form to an abstraction? Certain concepts, such as the Creature of the Id in Forbidden Planet, may be said to have their haunting quality by very reason of the indefiniteness of their outlines. Once bring an outline – a monster – and the force, far from becoming greater because of being more focused, can instead be undermined – fatal to the sense of wonder. All of which is connected with the thesis – and the controversy – centring on the Val Lewton films – the idea of “more with less”. Likewise as regards the demon in the brilliant movie Night of the Demon: should it have been brought in as a vivid concrete form, or left out? Some will say Yes, some will say No. In deciding on the latter example, for instance, the great critic Carlos Clarens would have said “Leave out!” (but I would say “Bring in”). Clark Ashton Smith’s Genius Loci is a very similar case. The wonderful tension, the sheer spookiness of the meadow on the Chapman Farm, would seem to be enough. The demonic possession of the artist, Amberville, and by degrees of his fiancée, and the helplessness of their friend, the author, are subtly and suggestively developed by Smith. And yet, I believe that the visible emanation from the evil of the meadow enhances rather than detracts from the subtleties and suggestiveness of the story. And this is because of the precise, balanced, and technically perfect handling by Smith. In this instance, as in many others among his writings, he proceeds pictorially as he would have painted, with an eye to the masses, shapes, colours, relationships of constituent effects. It is the rightness of the proportions of the story that make it work, rather than the virtue of any particular theory, and it is this proportionate eye that often makes the miracle of fantasy-writing work, and which enables rules to be triumphantly broken.

On a personal note, this writer means more to me the older I get! He is so full of surprises. The pessimism is shimmered into something else, and then the something else is shimmered into a pessimism. The nihilism – abracadabra! – is abundant with an eerie lushness, and the lushness shimmers into the emptiest nihilism – but wait, there is a glowing! We follow - and Lo! Out into another country, another world, another adventure!

So it goes, so Smith goes, and so I go – always back to the stories.

The term “genius” is easy to lob around, but of all fantasy-writers I think it most peculiarly applies to Clark Ashton Smith. And to the cliché asked now and then – “If you were confined to a desert island, which author’s works would you most want to bring? And the answer in my case, after I had thought for a while, and weighed everything up, would be -