- Home

- Mars and its moons

- Barsoom

barsoom - and the secret of erb's

world-building achievement

Nothing in the literature of the Old Solar System quite matches the ten linked volumes of Martian adventure by Edgar Rice Burroughs.

Stid: So much has already been written about them, that I question our ability to add anything useful to the sum of critiques.

Zendexor: Plenty remains to be said, I assure you. In fact, the most vital issue remains to be addressed.

"The thin air of dying Mars" - that's what is cleaved by the prow of your flier as you rise from the ground in search of adventure. Emblematic of the series is that image of flight into mystery.

And yet it's not a blank mystery. We're given the known and the unknown, together, in the right degree of balance.

Let me quote a three-paragraph passage from A Fighting Man of Mars -

In the adventure upon which I had embarked the destination control compass was of little value to me, since I did not know the exact location of Jahar. However, I set it roughly at a point about thirty degrees south latitude, thirty-five degrees east longitude, as I believed that Jahar lay somewhere to the south-west of that point.

Flying at high speed I had long since left behind the cultivated areas near Helium and was crossing above a desolate and deserted waste of ochre moss that clothed the dead sea bottoms where once rolled a mighty ocean bearing upon its bosom the shipping of a happy and prosperous people, now but a half-forgotten memory in the legends of Barsoom.

Upon the edges of plateaus that once had marked the shore-line of a noble continent I passed above the lonely monuments of that ancient prosperity, the sad, deserted cities of old Barsoom. Even in their ruins there is a grandeur and magnificence that still have power to awe a modern man. Down towards the lowest sea bottoms other ruins mark the tragic trail that that ancient civilization had followed in pursuit of the receding waters of its ocean to where the last city finally succumbed, bereft of commerce, shorn of power, to fall at last an easy victim to the marauding hordes of fierce, green tribesmen, whose descendants now are the sole rulers of many of these deserted sea bottoms. Hating and hated, ignorant of love, laughter or happiness, they lead their long, fierce lives, quarrelling among themselves and their neighbours and preying upon any chance adventurers who happen within the confines of their bitter and desolate domain.

Stid: Let me guess: you're going to use this passage, and others like it, to make a point about the achievement of the series: namely that it's full of movement, adventure and excitement against a background which is colourful and (given he built it up in ten volumes) detailed enough for us to feel that the whole is greater than the sum of its parts.

To the extent that he does make Barsoom solidly real in the reader's mind, it's because of that gift for narrative vividness. Go on writing in that vein for ten books and you're bound to end up having created something fairly substantial.

Zendexor: No, I am not going to make points of that sort. You, Stid, are trying to make out that there is no great mystery about the success of this series.

In fact, you're ignoring the huge risks that Burroughs runs as a writer.

Let's look again at that passage I quoted.

First, note the destination control compass (a pre-programmable steering-device for Barsoomian flyers). It, and the flyer itself, imply a high level of technical achievement by the dominant red men of Mars. Incidentally the narrator, Tan Hadron, tells us that his one-man scout flier "easily attains the speed of two thousand haads per zode" (about 300 miles per hour)...

Stid: So, what's the risk in all this?

Zendexor: That fliers will go too fast for the stories, that distances will be covered too easily, and Mars will shrink too far, that it will become in effect too crowded for the practical purposes of adventure into the unknown - as in the case of Tarzan's decreasingly believable Africa, where the reader gets to doubt more and more whether that continent can possibly contain sufficient surface area for all the lost empires and peoples which the ape-man encounters!

Stid: I get your point. I suppose, though, that if one takes it as seriously as you're doing, you will in any case find a whole lot of other obstacles to the necessary suspension of disbelief.

The inconsistencies, the reliance upon coincidence, the extraordinarily important role played by the need to rescue women - to such an extent that actual wars, Trojan-style, arise from abductions -

Zendexor: I get what you're saying, too, but I profoundly disagree. The line you're taking is the tolerantly dismissive line which many critics take - namely, that it's a waste of time to expect too much but that if you can accept the stuff in its own terms, for the sake of the story, then it's a pleasant enough bit of light reading.

But if that were all there was to it - if there were no bigger secret behind the creation of Barsoom - then the man would have had many successful imitators. After all, there can't be any lack of authors who'd like to become as rich as ERB did! And yet no one has rivalled ERB's sword-and-planet achievement. (For a comparison with an unsuccessful imitator, see the OSS Diary for 31st December 2016.)

No - we need to delve deeper.

ERB was jammy. He got away with a lot.

Above all we need to confront the boundary problem, which is at its most severe in connection with the way John Carter originally gets to Mars.

Ping! One moment Carter's on Earth, and the next - without any reason given - he's on Mars, and furthermore, he knows he's on Mars. Beat that for a plot! You're a writer, you want your hero to get to Mars, so - you just plonk him there. And that's that! But what a risk!

Stid: You mean - if he can teleport himself from world to world, then he can get out of anything, so it's hard to get excited by the scrapes he gets into.

Zendexor: Yes, or alternatively, if he can't teleport at will - and such is the case, for his interplanetary teleportation only occurs at rare intervals and the process seems not to be under his control - then what the heck is going on?

Harlei: And it's not even true that the process is never under his control. At first he can't control it but later - in the introductions to Swords of Mars and Llana of Gathol - he seems gradually to be learning. He makes the crossing with his Mars-wear rather than naked, for instance...

Zendexor: The closest Burroughs gets to giving us some kind of answer to the whole question is when Carter mentions that some Barsoomian thinkers have theories about his space-crossing ability. The theories remain mere theories - remarks Carter - but we can at least say that someone has an idea. That's the only concession Burroughs ever makes to the reader's bafflement. And the concession comes late in the series!

It's almost as if Burroughs were showing off how close he could approach the precipice of literary disaster.

Stid: Despite all you say, I'm still not convinced that there's a mystery about it. You talk of a precipice of literary disaster, as though you're saying that if a writer takes one wrong step too far, the worth of his whole effort collapses. But surely it's not "all or nothing" like that. Surely it's rather a matter of degree. Burroughs makes a heap of mistakes, but it so happens that his good points are good enough for his achievement to remain reasonably solid, for those who like that sort of thing. No mystery. No big secret.

Zendexor: The "matter of degree" comes into it, sure. But so does suddenness of result - both positive and negative.

Positively, we can say that the way to world-build successfully is to build up a certain critical mass of interconnected images and dramas and characteristics, so that they all gel into some holistic vision.

Negatively, we can say that it's still possible to blow up that world by some destructive lapse of taste or error of literary judgement which suddenly makes it all seem silly.

Or, if you don't agree with the "sudden total collapse" scenario - if you're a gradualist, Stid, rather than a catastrophist - you will nevertheless agree that the world-building could be undermined by a sufficient number of lapses, of inconsistencies, of implausibilities.

Now my point is that, given the number of such lapses, we ought to be surprised that the Barsoom achievement has not crumbled or evaporated!

The green men are fifteen feet tall. Carter, and others, frequently have sword-fights with green men. Can anyone explain to me how a six-footer could have a meaningful sword-fight with a fifteen-footer?

Stid: Carter can jump -

Zendexor: But the native red Barsoomians don't have his advantage of having been reared under Earth's gravity. They don't jump like he does. Yet fights aplenty happen between the human-sized red men and the fifteen-foot green men.

Another thing about those green men: despite their great size they occupy rooms in the deserted cities of old Barsoom, which were built to house people of normal human stature.

Harlei: Well, they may have had high ceilings - being palatial -

Zendexor: But not fifteen-foot doors!

No, the fact is, the green men vary in effective size, like King Kong in the movie - the giant ape inconsistently changing from being a hundred feet tall to being about twenty feet tall, depending on the requirements of the various scenes.

And there are so many other things that don't add up. In volume eight, Swords of Mars, two Barsoomians invent space flight - yet it is forgotten thereafter. It appears to have no effect on the world.

In volume one, the vital atmosphere-factory is almost unguarded; the security around it is so ridiculously lax, that the planet almost asphyxiates when the lone curator is assassinated.

Throughout the series, Barsoomians in their millions own fliers and use them - but the world is depicted as lonely and silent, and news appears not to travel very well. Huge tracts remain unexplored; whole cities remain undiscovered - fortunately for the plots of the stories, but hard to credit nevertheless.

Now it's time to stop and ask:

Why aren't all these points - and others I could make in the same vein - enough to undermine the whole show?

Stid: Because the reader doesn't want them to.

Zendexor: Is your lip curling in a slight sneer, Stid? Whether it is or not, you are touching upon a profound truth.

Barsoom, once the critical mass of invention has been reached, becomes not only an image-producing but also an excuse-producing work.

The reader is henceforth enlisted, his inner excuse-finder activated, so that when he spots an inconsistency, instead of swooping upon it and regarding it as a reason to abandon the books, he is instead prompted to embellish the series further, to create justifications and explanations for the discrepancy, and thus turn the author's lapse into a cause of yet further interest!

Take the business of space flight. Fal Sivas and Gar Nal invented spaceships in Swords of Mars but those inventors and their ships are not mentioned thereafter. So - let's think it out! Let's invent reasons! They might have been assassinated - they were enemies and were the type to have other enemies as well as each other. Or their inventions may have been impounded by the Heliumetic government. (In which case perhaps the spacecraft-technology might be dusted off and used again in the fight against the Jovian invasion that is foreshadowed in Skeleton Men of Jupiter...)

You see what I'm doing? It's a question of attitude. Barsoom has accumulated such power, that it becomes untouchable by criticism. Any negative flak is turned positive by the reader's inner converter, his excuse-manufacturing organ, which transforms inconsistencies into sources of further enrichment of the series.

That's why Burroughs can get away with so much. He effectively hires his readers to do his patching-up for him.

Fine - you may say - but is this not just to re-label the problem? How is such a hiring of readers to be achieved? And why have Burroughs' competitors and would-be imitators such as Michael Moorcock and Lin Carter not equalled his achievement?

Stid: You took the words out of my mouth. It's the question that needs answering on a literary level, Zendexor - not just by psychology.

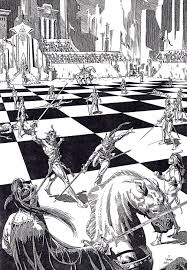

the chessmen of Mars

the chessmen of MarsZendexor: I agree. It's time to talk about style. Specifically, cadence - the rhythmic pacing of language - and the length and structure of sentences.

I don't think there's any point in trying to evade the conclusion that Burroughs is actually a great writer, embarrassing though this may be to critics who regard popularity and readability as incompatible with greatness.

But one can be more specific.

The Barsoom series is written in a mildly pompous style - 'pompous' in the good sense of the word: the good sense, I mean, as used in C S Lewis' A Preface to Paradise Lost in defence of Milton's style:

As for the style of the poem, I have already noted this peculiar difficulty in meeting the adverse critics, that they blame it for the very qualities which Milton and his lovers regard as virtues. Milton institutes solemn games, funeral games, and triumphal games in which we mourn the fall and celebrate the redemption of our species; they complain that his poetry is "like a solemn game". He sets out to enchant us and they complain that the result sounds like an encantation. His Satan rises to make a speech before an audience of angels "innumerable as the starrs of night" and they complain that he sounds as if he were "making a speech".

Stid: I've got to hand it to you, Zendexor - you've excelled yourself this time. Comparing ERB with Milton!!!

Zendexor: The rightful use of "pompous" does need some exercise now and then. And there is a markedly dignified side to ERB's prose and there are plenteous and beautiful cadences in his narrative, borne along on the sentence structure which I may summarize as follows:

Long build-up - turning-point - 'build-down' (or peripeteia).

And this is the way it goes:

As I rose above the towers and domes and lofty landing-stages of Greater Helium, I turned the prow of my flier towards the west and opening wide the throttle sped swiftly through the thin air of dying Barsoom towards that great unknown expanse of her remote south-western hemisphere, somewhere within the vast reaches of which lay Jahar, towards which, I was now convinced, Sanoma Tora was being borne to become not the Jeddara of Tul Axtar, but his slave, for jeddaks take not their jeddaras by force upon Barsoom.

[A Fighting Man of Mars, page 27.]

To reproach myself for my carelessness seemed a useless waste of mental energy, though I can assure you that I was keenly aware of my fault and of its possible bearing upon the fate of Sanoma Tora, from the active prosecution of whose rescue I might now be entirely eliminated.

[ibid., page 32.]

He was hurling himself as best he could against the trap-door, above which I stood with some misgivings, which were presently allayed when I realized that not even the vast strength of the white ape could avail against the still staunch and study skeel of the ancient door.

[ibid., page 37.]

You see - or rather you hear - how the tone soars, hovers, descends.

Sometimes, instead of integrally complex sentences like the one above, he chooses to link shorter sentences together with "and", but the effect is still well chosen - he has an unerring sense of when to do it, and when not to do it:

We overtook the fleet shortly before it reached the Twin Cities of Greater Helium and Lesser Helium, and upon the deck of John Carter's flag-ship we received a welcome and a great ovation, and shortly thereafter there occurred one of the most remarkable and dramatic incidents that I have ever beheld. We were holding something of an informal reception upon the forward deck of the great battleship. Officers and nobles were pressing forward to be presented, and numerous were the appreciative eyes that admired Tavia.

It was the turn of the Dwar, Kal Tavan, who had been a slave in the palace of Tor Hatan. As he came face to face with Tavia I saw a look of surprise in his eyes.

[ibid., page 192.]

Burroughs does not overdo the sentence-length; never have I come across a passage in which the structure buckles under its own weight and, as the above passage shows, he knows when to intersperse with shorter sentences.

But there's no doubt that the long sentences with the build-up / turning-point / build-down structure are vital to his style.

And this in turn lends itself, I believe, to his penchant for suspense.

It is wrongly assumed that Burroughs is first and foremost a writer of action-adventure. Adventure certainly, but as well as action he is a master of its opposite, namely, suspense.

For example, consider the scene in chapter 3 of A Fighting Man of Mars - seventh volume in the series, and perhaps its epitome - where Tan Hadron is trapped in the deserted tower by a great white ape. The scene is eight pages long, eight pages of doubts, hesitations, fears. It is a masterly, spellbinding, unforgettable piece of writing.

Any writer who can spin out the tension to that extent is worthy of critical respect.

He's not always as good as he is there, but he is safely past the point at which the reader's excuse-production facility kicks in, so that the liabilities turn into assets, as explained earlier on this page.

Another way of putting it is to say that his vision has created a world whose soil favours the growth of adventure, or whose very air is elastically biased towards the breeze of adventure, just as the day-old Narnia in The Magician's Nephew was conducive to replication of objects, or the environment of Tormance in A Voyage to Arcturus tends to coruscate and pop with physical change and metaphysical events.

In which case each scene may carry such a charge of self-justification, that no carping about consistency can possibly matter a hoot.

Or perhaps it may suffice to say that Burroughs, who was not stupid but was nonetheless not the most intelligent of writers either, simply struck lucky in the combination of his ideas, which provided the ideal material for his style to get to work on. Like a prospector for oil may drill in a lucky spot and - whooosh!

And if such wells are rare, it is all the less likely that a worthy imitator will be found.

If the Burroughs tradition of planetary adventure lives on it is more likely to do so in distant cousinage such as Valeddom and Uranian Gleams (though they do not match Burroughs' sonorous cadence of style), rather than in the attempts at pastiche such as Jandar of Callisto and the Kane of Old Mars series.

Better stop this page now - there's so much more to say, it will have to spill elsewhere. For more on Barsoomian cities, click here. For the ethical issues raised by the Barsoom books, see moral dimensions, and - with particular regard to the bloodthirsty games in the arena - the analogy with extra time-axes discussed in playing pick-up spectra.

For speculation on the origin of John Carter, see the OSS Diary for 25th August 2016.

For a scene in the pits of ancient Horz, on the shores of vanished Throxeus, click here.

For the Three Great Savants of Barsoom, see the OSS Diary for 24th July 2016.

For moral bipolarity among the rulers of Barsoom, see the OSS Diary for 29th July 2016.

For the moral issues surrounding the Sack of Zodanga in A Pricess of Mars, see the Diary,

Carter and Zodanga - How to Glide Over Dilemmas and From 1520 to Barsoom.

For lack of humanitarian interventions see Isolationism on Barsoom.

For psychological depth in The Gods of Mars, see the OSS Diary for 13th October 2016.

For the useful stalemate of radio and telepathic communcation on Barsoom, see the OSS Diary for 19th October 2016.

For Barsoom and the concept of the Golden Age, see the OSS Diary for 3rd November 2016.

For the "uncanonical" John Carter and the Giant of Mars, see the OSS Diary for 11th November 2016.

For some discussion of Synthetic Men of Mars and its inconsistencies, see the OSS Diary for 19th July 2016.

For GAWI and The Chessmen of Mars, see the OSS Diary, 25th January 2017.

For comparisons between Barsoom and Michael Moorcock's Kane of Old Mars trilogy:

see the OSS Diary for 31st December 2016, "At Martian Swordpoint -

How Not to Do It - and How To Do It";

for the apt, and comparative Martian zoology, see

the OSS Diary, 2nd February 2017;

for soliloquies, see the OSS Diary, 18th February 2017.

For parallelisms between Barsoom and the writings of Dumas, see "Planet D'Artagnan" in the OSS Diary for 22nd March 2017.

For the theme of Barsoomian arena-combat see the OSS Diary for 24th March 2017.

For scene-comparisons between A Fighting Man of Mars and examples in the Jandar of Callisto series, see Thanator - For and Against. For comparisons with Philip Roth's American Pastoral, see Martian Pastoral.

For the lack of thievery on Mars see Holiday from Explanation.

For the fake religion of the Phundahlians see The Worship of Tur.

For the Battle of Dor, in The Gods of Mars, see Decisive Battles of the Old Solar System.

For comparison between Barsoomian and Terran rulers, see Jasoomian Jeddak.

For a view that is favourable to Barsoom but unfavourable to John Carter, see The Worlds of Edgar Rice Burroughs.

For a work of reference and a critical study, see A pair of guides to Barsoom.

See Involuntary creation of OSS worlds for the idea that the collective unconscious might materialize Barsoom for real.

For the advantageous lack of Martian reporters see News travels slowly on Barsoom.

See the Diary entry which discusses the possible political snags to the brain transplants in The Master Mind of Mars.

For a sharp contrast see Travel and its effect on Martian civilization in Brackett and Burroughs.

For thoughts on a phrase see Homage to Barsoom - "sleeping silks and furs".

For chronology see Martian years / Earth years - a minor gripe.

Also, John Carter blunders again with the Barsoomian year.

For "discompetence" see Planet of restraint.

And see the Diary entry on the Disney movie John Carter.

For a stunning real-life equivalent of the north polar barrier described in The Warlord of Mars, see Perfect setting for the Carrion Caves.

Excerpts: see Mad Martian's Palace ... A mysterious park-like area on Mars.

Edgar Rice Burroughs, the Barsoom series: A Princess of Mars (1912, 1917), The Gods of Mars (1913,1918), The Warlord of Mars (1913-14, 1919), Thuvia, Maid of Mars (1916, 1920), The Chessmen of Mars (1922), The Master Mind of Mars (1928), A Fighting Man of Mars (1931), Swords of Mars (1936), Synthetic Men of Mars (1940), Llana of Gathol (1941, 1948); Lin Carter, Jandar of Callisto (1972); Robert Gibson, Valeddom - Mercury Awaits (2013); Uranian Gleams (2015); C S Lewis, A Preface to Paradise Lost (1942); The Magician's Nephew (1955); David Lindsay, A Voyage to Arcturus (1920); Michael Moorcock, the Kane of Old Mars series: City of the Beast (1965), Lord of the Spiders (1965), and Masters of the Pit (1965)

Recommended critical works / surveys: Richard A Lupoff, Barsoom: Edgar Rice Burroughs and the Martian Vision (1976); John Flint Roy, Guide to Barsoom (1976).