eerie earths

[ + link to podcast on A Trip to the City ]

Our world is bigger than geophysicists think... for it is enlarged by being charged with that Shimmer which has accumulated like static from the extensions and alternates - the dimensional nooks and crannies - envisioned in sf literature.

To invite you for a closer look at Earth's propensity for eerie enlargement, I have chosen a couple of superb tales which, though differing in mood and style, equally leave a reader wondering at the vast unknown reaches of a supposedly familiar planet.

End of the line

A Trip to the City begins with a train journey. A restless young American named Brett Hale leaves his small town of Casperton to seek his fortune. He falls asleep on the train. When he wakes, he goes to the toilet, and then finds the lock is jammed - and by the time he breaks out, the train has stopped and the carriage is empty.

He was looking out the open door and through the window beyond. There was no platform, just the same dry fields he could see on the other side. He came out and went along to his seat...

Brett is fairly unflappable. Not the sort to go wobbly as the evidence mounts that something beyond strange has happened.

He looked out the window. Why had the train stopped here? Maybe there was some kind of trouble with the engine. It had been sitting here for ten minutes or so now. Brett got up and went along to the door, stepped down onto the iron step. Leaning out, he could see the train stretching along ahead, one car, two cars -

There was no engine.

Maybe he was turned around. He looked the other way. There were three cars. No engine there either. He must be on some kind of siding...

Don't misunderstand - this story is not yet another "falling into another dimension" tale. Far more creepily than that, it seeks to convince us that we don't actually know our own dimension.

Brett stepped back inside, and pushed through into the next car. It was empty. He walked along the length of it, into the next car. It was empty too.... All the cars were empty. He stood on the platform at the end of the last car, and looked back along the rails. They ran straight, through the dry fields, right to the horizon. He stepped down to the ground, went along the cindery bed to the front of the train, stepping on the ends of the wooden ties. The coupling stood open. The tall, dusty coach stood silently on its iron wheels, waiting. Ahead the tracks went on -

And stopped.

He walked along the ties, following the iron rails, shiny on top, and brown with rust on the sides. A hundred feet from the train they ended. The cinders went on another ten feet and petered out. Beyond, the fields closed in. Brett looked up at the sun. It was lower now in the west, its light getting yellow and late-afternoonish. He turned and looked back at the train. The cars stood high and prim, empty, silent. He walked back, climbed in, got his bag down from the rack, pulled on his jacket. He jumped down to the cinders, followed them to where they ended. He hesitated a moment, then pushed between the knee-high stalks. Eastward across the field he could see what looked like a smudge on the far horizon...

Stid: Evidently a stolid type.

Harlei: You think his mind ought to be seething with theories, speculations? Maybe it is! But maybe the speculations are numbed by the awful weight of sheer unanswerable fact... in which case, the author does right to show us Brett just plodding along the line, rather than broadcasting his stream-of-consciousness to us the readers. It's better technique, at this point.

existential suspicion

Zendexor: True, but both of you, Harlei and Stid, have missed something at the beginning of the story: it's the bit when Brett Hale thinks back to the quarrel he'd had with his girl-friend before he left town.

He had annoyed her with his ornery habit of criticizing certain peculiarities of ordinary life which most people take for granted:

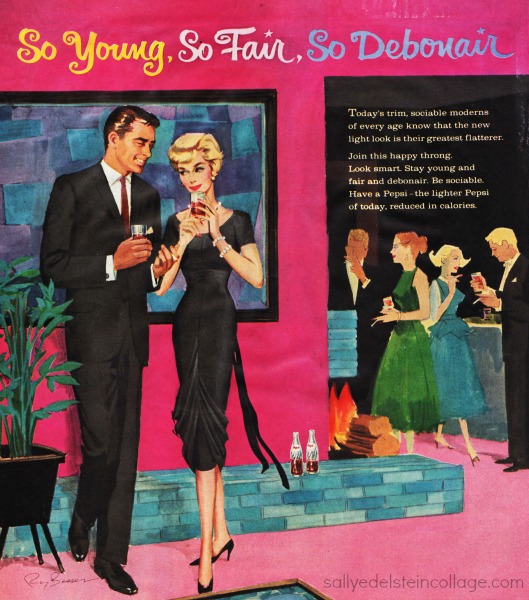

She had been sitting at the counter at the Club Rexall, drinking a soda and reading a movie magazine with a big picture of an impossibly pretty face on the cover - the kind you never see just walking down the street. He had taken the next stool and ordered a coke.

"Why don't you read something good, instead of that pap?" he asked her.

"Something good? You mean something dry, I guess. And don't call it... that word. It doesn't sound polite."

"What does it say? That somebody named Doll Starr is fed up with glamor and longs for a simple home in the country and lots of kids? Then why doesn't she move to Casperton?"

"You wouldn't understand," said Pretty-Lee.

He took the magazine, leafed through it. "Look at this: all about people who give parties that cost thousands of dollars, and fly all over the world having affairs with each other and committing suicide and getting divorced. It's like reading about Martians."

And although Pretty-Lee protests that there's nothing wrong with reading about movie stars, Brett intensifies his criticism of media-unrealism as he goes on to pour scorn upon a full-colour advertisement on the back of the magazine.

"Look at this. Here's a man supposed to be cooking steaks on some kind of back-yard grill. He looks like a movie star; he's dressed up like he was going to get married; there's not a wrinkle anywhere. There's not a spot on that apron. There isn't even a grease spot on the frying-pan. The lawn is as smooth as a billiard table..."

And on and on he goes, till it's too much for the girl.

Pretty-Lee grabbed her magazine. "You just seem to hate everything that's nicer than this messy town - "

"I don't think it's nicer. I like you; you hair isn't always perfectly smooth, and you've got a mended place on your dress, and you feel human, you smell human - "

"Oh!" Pretty-Lee turned and flounced out of the drug store.

Stid: I'm getting the idea. This is that kind of story where the author seizes upon some familiar, taken-for-granted weirdness - in this case, the mis-match between advertising or reportage, on the one hand, and reality on the other - and then proceeds to suggest a different explanation from the usual one, a creepier answer than anyone else has thought of. Here, a streak of independence in Brett Hale has already allowed a seed of cosmic suspicion to get planted in his mind...

Zendexor: We can guess along these lines, yes. It's a surreal, suggestive story which does not provide neat answers, but it works because of its dusty realism, and the soundness of Brett's character and nerves. Whatever else may turn out to be fake, Brett's actions show that he knows good and bad to be real, and that's all he really knows, as he encounters the mysteries and perils, the aliens and the golems inhabiting a hollowed-out city.

He also instinctively feels his way around the unspoken rules that determine survival.

don't over-step the mark - or else

"What's... uh... how do you spell the name of this town?" Brett asked.

"I was never much of a one for spelling, sir," the waiter said.

"Try it."

"Gravy, sir?"

"Sure. Try to spell the name."

"Perhaps I'd better call the headwaiter, sir," the golem said stiffly.

From the corner of an eye Brett caught a flicker of motion. He whirled, saw nothing...

The city is not completely devoid of real people. One of them, another young man, a cheerful free-loading type, befriends Brett.

But he seems to come from a quite different culture.

"Those clothes," Dhuva said. "And you have a strange way of talking. What county are you from?"

"Jefferson."

"Never heard of it. I'm from Wavly. What brought you here?"

"I was on a train. The tracks came to an end out in the middle of nowhere. I walked... and here I am. What is this place?"

"Don't know." Dhuva shook his head. "I knew they were lying about the Fire River, though. Never did believe all that stuff. Religious hokum, to keep the masses quiet. Don't know what to believe now. Take the roof. They say a hundred kharfads up; but how do we know? Maybe it's a thousand - or only ten. By Grat, I'd like to go up in a balloon, see for myself."

"What are you talking about?" Brett said. "Go where in a balloon? See what?"

"Oh, I've seen one at the Tourney. Big hot-air bag, with a basket under it. Tied down with a rope. But if you cut the rope...! But you can bet the priests will never let that happen, no, sir." Dhuva looked at Brett speculatively. "What about your country: Fession, or whatever you called it. How high do they tell you it is there?"

"You mean the sky? Well, the air ends after a few miles and space just goes on - millions of miles - "

Dhuva slapped the table and laughed. "The people in Fesseron must be some yokels! Just goes on up; now who'd swallow that tale?" He chuckled.

Dhuva's precept is: just believe what you see.

He does not, however, believe in doing anything about the smoky ectoplasmic aliens who patrol the city.

"The Gels? They run this place. Look out for them, Brett. Stay alert. Don't let them see you."

"What do they do?"

"I don't know - and I don't want to find out. This is a great place - I like it here. I have all I want to eat, plenty of nice rooms for sleeping. There's the parades and the scenes. It's a good life - as long as you keep out of sight."

But at least Dhuva can tell who's human and who isn't.

"...A live man moves different than a golem. You see golems doing things like knitting their brows, staring back in alarm, looking askance, and standing arms akimbo. And they have things like pursed lips and knowing glances and mirthless laughter. You know: all the things you read about, that real people never do..."

So there it is again: the message of the story in another guise: the media, in this case the literary media, distort and deceive...

However, another human whom Brett meets won't go so far as to admit that anything unusual is going on at all.

"I'm talking about the brown things; they look like muddy water. They come around if you interfere with a scene."

The fat man looked nervous. "Please. Go away."

"If I make a disturbance, the Gels will come. Is that what you're afraid of?"

"Now, now. Be calm. No need for you to get excited."

"I won't make a scene," Brett said. "Just talk to me. How long have you been here?"

"I dislike scenes. I dislike them intensely."

"When did you come here?"

"Just ten minutes ago. I just sat down. I haven't had my dinner yet. Please, young man. Go back to your table." The fat man watched Brett warily. Sweat glistened on his bald head.

"I mean this town. How long have you been here? Where did you come from?"

"Why, I was born here. Where did I come from? What sort of question is that? Just consider that the stork brought me."

"You were born here?"

"Certainly."

"What's the name of the town?"

"Are you trying to make a fool of me?" The fat man was getting angry. His voice was rising.

"Shhh," Brett cautioned. "You'll attract the Gels."

"Blast the Jilts, whatever that is!" the fat man snapped. "Now, get along with you. I'll call the manager."

"Don't you know?" Brett said, staring at the fat man. "They're all dummies; golems, they're called. They're not real."

"Who're not real?"

"All these imitation people at the tables and on the dance floor. Surely you realize - "

"I realize you're in need of medical attention." The fat man pushed back his chair and got to his feet. "You keep the table," he said. "I'll dine elsewhere."

"Wait!" Brett got up, seized the fat man's arm.

"Take you hands off me - " The fat man went toward the door. Brett followed. At the cashier's desk Brett turned suddenly, saw a fluid brown shape flicker -

The terror increases, there is a blaze of action and escape, but the story remains as eerie as ever, and achieves a memorable ending that is true to the message.

how much to explain

Stid: I don't think you and I need to argue about the merits of this tale. We can agree that it's top-notch science-fiction - though I don't know quite how Laumer gets away with it -

Zendexor: Those are the best kind: the ones that beguile, like a conjuring trick. It's always a case of balance, and there is no formula for it except genius.

Harlei: I think Stid is worried about the contradictions, like when you ask yourself, "When is this story supposed to be set? In the present or the near future, or the far future?" Well, you could compose a justification for it being set in the far future, where various cultural patterns have been frozen - like a further-future version of Time Out of Joint -

Stid and Zendexor together: No.

Stid: You're missing the point.

Zendexor: Just for once I agree with Stid. What you say, Harlei, might be true, but it isn't necessary to think along those lines. It actually isn't important. A Trip to the City could, most terrifyingly, be set in the present - in fact I think that is most in accordance with the spirit of the tale. It is more on the lines of Heinlein's They, the classic solipsist speculation; both lay extreme emphasis on the need to see for oneself - to distrust all hearsay and all media.

Stid: And so long as that's the theme, the stories - however wildly fantastic - can be classed as sf; as philosophical sf.

Harlei: In fact you get the best of both worlds in tales like this. The frisson of the supernatural or the fantastic can combine with the material thrill of sf.

Stid: Whereas if I mistake not, Zendexor is about to strain the definition of sf too far. Look - get ready for "over-stretch" - he's placing The Autumn Land next to his keyboard...

Zendexor: See for yourself. Let this infinite corner of Earth introduce itself.

He sat on the porch in the rocking chair, with the loose board creaking as he rocked. Across the street the old white-haired lady cut a bouquet of chrysanthemums in the never-ending autumn. Where he could see between the ancient houses to the distant woods and wastelands, a soft Indian summer blue lay upon the land. The entire village was soft and quiet, as old things often are - a place constructed for a dreaming mind rather than a living being. It was an hour too early for his other old and shaky neighbor to come fumbling down the grass-grown sidewalk, tapping the bricks with his seeking cane. And he would not hear the distant children at their play until dusk had fallen - if he heard them then. He did not always hear them.

There were books to read, but he did not want to read them. He could go into the back yard and spade and rake the garden once again, reducing the soil to a finer texture to receive the seed when it could be planted - if it ever could be planted - but there was slight incentive in the further preparation of a seed bed against a spring that never came. Earlier, much earlier, before he knew about the autumn and the spring, he had mentioned garden seeds to the Milkman, who had been very much embarrassed.

Stid: A place where it is always autumn; a place where nothing ever happens. Where a shadowy Milkman with a capital M brings you whatever you need and never asks for payment. You can't call that science-fiction.

Zendexor: I reckon you can, because the power of the human mind to create, or to attract, or to summon, a dimensional refuge against the intolerable certainty of an atomic war, is a fit topic for science-fiction.

But let me add that in a sense something does happen, eventually, to each person who finds himself or herself in the Autumn Land. It is the most exciting thing -

When you're ready, you move on.

The protagonist, Nelson Rand, is not ready. Not yet.

The path came to an end, its faintness finally pinching out to nothing. The groves of trees and thickets of low-growing shrubs gave way to a level plain of blowing grass, bleached to whiteness by the moon, a faceless prairie land. Staring out across it, Rand knew that this wilderness of grass would run on and on forever. It had in it the scent and taste of foreverness. He shuddered at the sight of it and wondered why a man should shudder at a thing so simple. But even as he wondered, he knew - the grass was staring back at him; it knew him and waited patiently for him, for in time he would come to it. He would wander into it and be lost in it, swallowed by its immensity and anonymity.

He turned and ran, unashamedly, chill of blood and brain, shaken to the core...

An experience can be too much when you take it at the wrong time. Nelson Rand learns patience in the autumnal village while his quiet neighbours, of longer standing, become ready sooner...

Stid: Ready for what? Oh, all right, I guess I shouldn't ask sharp questions; it's a mood piece, I realize. And yes, the way you look at it, Zendexor, it can count as science-fiction. After all, no one would deny that Childhood's End is science-fiction, yet that book has humanity's mind-powers exerting a huge potential influence on the Universe.

But about this Eerie Earths page in general, can I say something which dissatisfies me? We're supposed to be doing a Solar System web-site, aren't we? And all right, Earth is a planet in the Solar System, but I get so I want a whiff of interplanetary perspective...

Zendexor: That has been provided elsewhere, e.g. Dylan's page on humanity's place in the OSS. Still, there's no reason why we shouldn't also have more "blinkered" pages, which focus on just one world considered on its own. The Amtor page just deals with Venus, after all - the Amtorians don't even admit that other worlds exist! No whiff of interplanetary perspective there!

So, it's equally legitimate to treat Earth on its own, to pick out its special features. And the Shimmer is as much a special characteristic of Earth, as are the Rings for Saturn.

Arthur C Clarke, Childhood's End (1954); Philip K Dick, Time Out of Joint (1959); Robert A Heinlein, "They" (Unknown, April 1941); Keith Laumer, "A Trip to the City" (Amazing, January 1963; reprinted in Nine by Laumer (1967); Clifford D Simak, "The Autumn Land" (The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, October 1971; reprinted in The Autumn Land and Other Stories (1990))

>> Earth