enceladus erupts

by

robert Gibson

This tale is intended to fit into the same universe as The Arc of Iapetus, though perhaps a bit earlier.

One of the quietest, yet strongest creatures ever to inhabit the Solar System came to a decision. Resolve was boosted with a matching surge in physical density and power.

The opportunity had arrived, and he felt he must ride it. Risky, yes, but to be alive at all must mean an acceptance of inevitable risk; and from what he could see through the 'scopes, conditions on his neighbour world demanded prompt action.

For he knew what he was, and he knew what the Enceladans were.

Since this morning, Hixten’s self-awareness had blossomed to the extent that he knew himself to be a Tethyan - knew the exact word - because the very idea of a name was one of his borrowings, one of his now-native possessions. It mattered little where the word "Tethys" came from, what precise swirl he'd grabbed it from, out of all the swarms of data that blew along the etheric currents of the System. What counted was that henceforth it denoted his world and focused his loyalty. As for his personal name, that burst of sound “Hixten”, it too had sloughed its origin. By an edict of will it had become intrinsic, grounded in the present moment, unquestionable. From today he, Hixten the Tethyan, was this particular vortex of identity and no other.

As such, he foretold a lonely fate for himself. Why did he so strongly suspect that he was unique? Why had the transition from energy-creature to material organism been successfully accomplished by no other being of whom he was aware?

The other moons of Saturn, and the other planets and their moons, were (as far as his mental radar could discern) all populated by naturally organic entities, built of slow, heavy stuff. Their natures were so vastly less forceful than his, that he felt dubious about ever being able to relate to them. Were he to reveal himself to them, they would be terrified of him. Perhaps with reason.

Or was this outlook pessimistic? He must take into account that he was on the way to becoming heavy stuff too. Already his density was greater than that of water... and soon he would be able to disguise himself as a product of organic evolution. Then what? He might either to pose as one of the equatorial conical Tethyans, or as one of the rarer humanoid telemorphs who had developed at the northern pole of this little world. In fact he might try both… but first, he must deal with an emergency.

He had been busy fashioning the observatory equipment while all these thoughts were buzzing through his solidifying brain. How much easier it would have been to spy on the Enceladans while still immaterial – if only a roving intelligence could probe them without rousing them! Useless to wish that. The only way was the material way, Hixten had learned for sure. To haunt them in disembodied fashion was to invite disaster; he had been lucky, earlier, to escape being flung all the way into the Sun.

Now… if he could get away with just one certain glimpse…

In passing, as he approached the metallic shine of the projectile-tube which extruded from his observatory, Hixten noticed from the shape of his own limbs that he had become human. Well, he rather liked the style. The next few moments would decide whether he'd be given time to go on with it.

He sat down, grasped the handles of the cannon unit, and pulled the entire pivoted structure towards him. Chin on rest, he peered through the viewer and, with all his effort, hurled his mind at the inner moon.

It was the instant of local syzygy – the straight-line configuration of Tethys, Enceladus and Saturn – during which the ancient Saturnians’ Highway, the Yimdi Hsad, flicked into and out of existence. Hixten felt free to use it because he quite rightly assumed, in accordance with background knowledge common to all the inhabitants of the Nine Moons, that the mighty Saturnians could not care less who availed themselves of their vastly superior infrastructure. “Let them dabble,” was the attitude of the condenscending Yimdians, those Lords of the Ringed World who nowadays had little use for the Highway they had built in aeons gone by. Long ago they had progressed to the construction of ships, the grey globes that patrolled the ether and kept the peace among the Moons.

The peace that was threatened by Enceladan giants.

Now in the

instant that the Yimdi Hsad was a solid path, Hixten slid a densified

power-bar along it to the inner moon. Instinct ruled at least eighty per cent of his procedure; only in a limited

sense – so he trusted – did he need to know what he was doing. The essential was the

result. He must deal a blow and not suffer retaliation.

The time it took his power-bar to cross the 35,000 miles of space between the two little worlds was the longest fraction of a second he was ever likely to experience… far too short, though, for him to take subsequent precautions. If a prompt rebound occurred, he’d just have to take it. He sat back and mopped his brow. With every instant that passed the likelihood grew that he had gotten away with his action. Yes, he had, he had – and in reaction he sprang erect and raised his arms in triumph.

Hixten's heart thumped, the blood pulsed in his veins, and he felt fully human, all the way through. Triumph! Now to examine the recording, to see how, if at all, the Enceladans had reacted to being poked...

Reverently he pressed the buttons which duly presented him with the screen image he had hoped to see. A most welcome image that showed eminently vulnerable targets. Satisfying to reflect, that the time spent in an operation was no guide to the enormous sense of accomplishment with which success could reward the achiever. The work of a moment had given him THIS: a picture of the giant feathery trees of Enceladus, and what was more, it was a tell-tale picture in which each tree wore an unmistakable expression.

That was the key to it all. The snapshot, despite its stillness, caught the way they waved, those dimensionally liminal plants, “accelerants” as biologists called them because of the increasing fade at the upper fringes where each tree seemed to disappear via a fractal smudge into a higher nature. On the day that all of it became visible, that nature would pose a dire threat to Tethys.

Lest any doubt remain, a skeptic examining the picture need only ask himself, where were the other Enceladan life-forms? None visible, except for a few froglike creatures and the silver fur of grass and moss over which they hopped. All larger creatures were gone. The trees tolerated no rival on their world. That, in itself, was a good enough reason to oppose their expansion onto other worlds. Hixten had no doubt that his employers would see it that way too.

Hixten opened the door of his observatory and stepped out. He had been told to lose no time in reporting his findings to his “superiors”. Ha, that was a laugh. Rather than "superiors", better to say, “those who had commissioned him”; but it didn’t matter much. Adjustment of terminology could wait another twenty-five hours or so, for the next and decisive syzygy... Meanwhile he could enjoy the stroll to the Stod Rinnerul.

That advance base of the Tethyan humanoids, here in this equatorial Tethyan province of Dromm, stood within walking distance of Hixten's observatory. He trod a gleaming path, through a landscape of muted colour. Most of his body was almost weightless, and he swayed with each step; only his boots were attracted at all firmly by the short-range surface gravity of the small Saturnian moon. Gravity, here, was not of mass but of life. Whenever he glanced down he could see its source, the ubiquitous carpet of ultra-dense, many-hued diversity of lowly life. A crowded smallness was its theme. The range of its visibility, likewise, obeyed a law of limitation. The landscape’s richness stretched only so far. Its zone moved as he moved. Ever shifting, it extended around him in a circular zone of about five hundred yards’ radius. With each step he took, the icy blur that showed beyond the circumference followed and receded.

On his way to the Stod Rinnerul he met some of the dominant native Tethyans, the conical Tlel, who gyrated continually as they whizzed by. In this district of Dromm it was not unusual to meet several dozen of these mysterious and highly intelligent beings as they went about their incomprehensible business. Most of them topped Hixten in height; all of them exceeded him in weight. With their four muscular arms and their deep-seated almost invulnerable brains, they could have easily overcome any humanoid in a fight: no punch could stun a Tlel. Fortunate that they were un-hostile!

He gained the impression that some of them, as they passed him, bestowed on him more piercing glances than usual. He could not be sure of this since their quartet of eyes whirled round so fast; but it could be that these particular Tlel were surprised to spot a humanoid here in the equatorial zone. On the other hand, if that was so, they themselves must be strangers in the vicinity, since humanoid staff had occupied the Stod Rinnerual for several hundred days now. Or another explanation could be that he, Hixten, had become extra important in the past few minutes.

Anyhow here was his destination, where speculation became needless.

Without slackening his pace he walked up a cobbled path. The house he faced was formed mostly from a pattern borrowed from Earth. Even the roof seemed thatched, though not from straw but from stringy grey moss. On the other hand the walls’ glow was indigenous, their blocks shining with the neon nacre of a Saturnian ice-moon. To a local humanoid like Hixten, who had never seen Earth and never would, the effects were integrated into one comfortably familiar style.

Inside, his

sense of normality ebbed somewhat he was invited to sit down at a

conference table with a pair of interlocutors. One was a human whom he recognized: a smart woman, with flinty good looks. A small point nudged his attention: this Head of

Station, Elspeth – a name fashionably borrowed from Earth – was keeping her

hands under the table.

Ah well – thought Hixten – if she does not trust me, I nevertheless need not be offended. Another mistrust sort of compensates, for it works both ways:

This was the towering

presence of Onsa the Tlel, whose conical torso bulked

beside Elspeth’s chair. Tlels were guarantors of honesty in discussion. They could not read minds but they could

infallibly discern whether or not a speaker was lying: and if lies were told, Tlels corrected them

on the spot. It was possible that Elspeth hoped that the presence of the Tlel would help her to trust that power-wielder Hixten...

“Ready,” she asked without preamble, "to tell us of the success of your Dimensionless Grip?”

“I am,” said Hixten, meeting her forthrightness, eye to eye. “All went well at the crucial first stage.”

“The next alignment, then,” said Elspeth.

“The next,” he agreed, while

wondering whether he could go now, since it appeared that brevity was such a key note of the meeting.

It seemed however that more remained to be said. The voice-box which hung like a medallion just below Onsa’s front eye gave off a preliminary crackle.

“You can’t kill the Enceladans, you know,” the voice grated, toneless but colloquial. “Whether you ought to, is a question we need not face – certain it is, that they cannot be killed. The most we can hope for is to restrain, suppress – “

“Knock them flat,” Hixten finished for the Tlel.

"You can do that?"

"It's what I intend. Flatten them; mow them down."

“Like mowing an Earth lawn?"

Hixten shrugged, "That sounds right."

"If it is, then you imply,” said Elspeth, leaning forward, “that you will need to keep doing it.”

Hixten replied with a shake of the head, “The analogy is not necessarily that close. I rather think that one treatment will be enough.”

Elspeth blanched; she stared at the man for some seconds in the manner of one who weighs one peril against another… He, for his part, could easily guess that he had alarmed her with his confidence and power.

Yet when she spoke, she seemed altogether to change the subject of her mood. “Before you leave here, Hixten, I wish to give you some more data.”

“About the Enceladans? What can be known – “

“No. About yourself.”

He sat back easily, uninterested but prepared to listen. This woman could not be expected to understand how little he cared about his own origin. To him, the past was just wrapping paper around the prize which was the present; still, let her have her say.

He therefore listened patiently to the drone of facts which buzz along underneath the over-arching super-fact of the present; buzzings hardly worth the bother of a nod, their importance dissolved into the brimming reality of Now, over which he, Hixten, presides as the emperor of fact.

“…Almost all of the System’s worlds,” Elspeth droned, “show a dual approach to the evolution of intelligent life, in accordance with the profound principle of metadiversity. You have to have metadiversity in order to avoid the paradox of diversity in its simple form which just spreads itself uniformly and thus contradicts itself. To see how Nature did better than that, we need only ask the question, What can be more diverse than diverse? – and get the successful answer: A collaboration between the uniform and the diverse. Hence by this double performance the planets and moons of Sol tend to be peopled with, on the one hand, humanoid telemorphs - life drawn into human shape by the sun’s anthropogenic rays - and, on the other hand, a variety of native races unique to each world, evolved from local forces. So much is well known, and recognized as the explanation for the cultural and biological richness of our worlds, but recent research has indicated that even this bipolar metadiversity is not the furthest reach of the gamut of life. We have discovered what you might call a third axis of bio-space.”

She turned to the Tlel, whose voice-box in turn began to buzz:

“Enceladus is the exception which forced us to amend our theories.

“Enceladus is almost all water. Its density is hardly more than 1.0. You might suppose therefore that it lacks scope for bio-diversity of any kind. And yet it seems that Nature will not be denied. If evolution is denied one path, it will find another.”

Hixten was neither bothered nor bored; while he listened he cared only that nothing could stop his progress towards the next syzygy and his triumphant confrontation with the giants of the watery moon. It would have been easy to deflate Tlel. "Get on with it," he, Hixten, might have said. "Let's do without the needless suspense." For the conical Tethyan was obviously about to flourish something. But let Tlel have its surprise. What was it anyway? Ah… a book.

“This,” said Elspeth, taking the object from the Tethyan, “is a self-help text, imported all the way from Earth. Its title: You Can Be Anything You Want To Be.”

She said it with the corners of her mouth turned down, and from the grimth in her tone Hixten had no trouble in foreseeing the mood, though not the contents, of the rest of her speech. Still he did not worry in the slightest. Child's play to draw one's well-being from the veins and capillaries of the present environment, the bulge of the world around and underneath him, the endless spin of the other moons and planets, and his own inexhaustible ego!

“I don’t suppose that the author of this,” Elspeth brandished the book, “could have meant its title literally, but he was on to something. YOU, Hixten, are the exemplar of that principle made true. YOU have been, can be, what you want yourself to be. Look into yourself. Look deeply enough and you’ll know where you came from. Ah, did I see you flinch a tiny bit? No?"

Hixten remained obstinately silent. Elspeth continued:

"A few score days back, in an expedition to you-know-where, some of us obtained a particle of the life-system belonging to that third bio-space which I mentioned a minute ago. We bottled the force, cultivated you fast, encouraged you (with Tlel’s permission) to grow down the humanoid path, and gave you a human name.”

“What you’re saying,” Hixten observed calmly, “is that I am an Enceledan.”

“Yes.”

He refrained from saying And you want me, an Enceledan, to save this world from that one? Refrained – because she most likely knew the answer: that he was himself alone.

“Origins,” he allowed himself to scoff. “Who needs ‘em?”

“Not you,” agreed the voice of Tlel. “Soon, if all goes well, you will be Emperor of Tethys, provided that you can prevent the ice-giants’ conquest of our world.”

Elspeth concurred: “It's the price we are willing to pay. You as our ruler for the rest of your life.”

The meeting, he realized, had achieved its fair purpose: all three beings in the room understood each other, with no blame attached to the outsized ego by which alone the threat from the inner moon could be defeated.

All he now need do, was go back to the Observatory and wait for the imminent opportunity to carry out the act of destruction which would seal the bargain between himself and those who had helped him to existence.

However, he retained an image which impressed him: that of the woman Elspeth – mature, severely beautiful, delicate features surmounted by silver curls. And along with these, something in her tone which pronounced him to be damned.

Back at the Observatory, he mulled over the question, why he should care about her tone, and alongside such reflections he began to modify his plans.

One advantage of living in the present moment was that he found it easier than would otherwise have been the case to ignore the possibility of danger to himself. Danger was in the future. The idea of being damned was a different case. If true, then it was a negative quality which hung about him already. It should be dealt with right now.

It was not hard to amend the procedure for victory. He need not even put his actions into words – he had no assistants who might have required explanations, and he need leave no record. The result was all. Either it happened or it didn’t.

Originally he had intended an instantaneous, brute intensification of the Dimensionless Grip which would “knock them flat”, and that must still be the main blow to strike, but he determined on two alterations to the plan. First, rather than hurl the blow at the moment of syzygy, he would arrange a timer with some minutes’ delay. Second, he would hive off a small portion of the force… arranged so that when the main blow was struck, he himself would be on Enceladus. He would take his own medicine.

He modified the apparatus and, during the hours of waiting, amused

himself with study of the mysterious workings of his own mind.

Syzygy came: and while the timer began to tick, Hixton rode ahead, part of his own force-beam. After an instant's tumbling exposure to eternity he found himself, with his balance recovered, upright upon the silver-grey surface of Saturn's second moon.

With a sudden overwhelming sense moral relief, of all debts paid off, Hixten relaxed with his arms limp at his sides. Slowly he turned, to view the panorama which surrounded him.

Lined up on the close horizon were the feathery giants, the tree-like Enceledans, but his attention was drawn to other, much closer creatures as he became aware of metallic, tinny sounds, which came from shapes that hopped along the icy ground. These must be the frog-like things he’d previously glimpsed through the ‘scope, except that from close up they were nothing like frogs: they were three-legged, and their spade-like beaks (larger than their torsos) continually opened and shut with a continuous clank-clank.

With the spirit of a mere hobbyist or dilettante, Hixten crouched to examine the clankers.

He dealt a dismissive mental kick at the idea that he was pressed for time. Far from it, he told himself; he had several minutes of time, which in his present mood could stretch into a sizeable vacation, a drawn-out binge of “I’ve done enough; I can please myself now.” Why should he not allow his attention rove where it willed? He had made his sacrifice and now he felt a rush of distaste for big things; his curiosity drew him instead to the small clanking creatures and their even smaller prey.

Snap, snap went the beaks as the clankers picked at a scatter of faint red rings which tinged the icy ground.

Their little circumscribed lives were about to extend in scope and potential. Soon, when the big things were gone, when the tree-giants were crushed by the oblong bolts of force which would arrive within minutes from now, small beings would get their chance to become the dominant thrivers on Enceladus; so he guessed. And he, Hixton, might with some complacency take credit for that. The thought made him all the more inclined to rest on his self-awarded laurels and do nothing more but wait for the end.

On the other hand – he could sense it about to happen - moods have a tendency to rebound.

Thus, when the voice came at him, he said to himself: I knew it, I knew the kind of knock that was on the way.

The ball of meaning was suddenly inside his head, but thrown from a long way off, all the way from the horizon in fact: thrown at him by the giant feathery trees, the lords of Enceladus. The ball said: Come and talk to us before the end.

He replied with emotion only, unable to form a clear message, and immediately the second ball came hurtling:

We understand your reluctance to move towards us. While you remain close to the clankers you can enjoy the sniff of their dense causality, their status as genetic creatures, subjects of reasoning science, an ambience which enables you to hope, in principle, that you might discover how you yourself had been brought into human form…

No! he hurled back, I don’t care about that sort of stuff at all! I live in the present and don’t give a scrap for origins!

So you say, Hixten, but we know you better than you know yourself. You are, after all, basically one of us. You’d certainly care to know how your modification into human form was done. And it would not be impossible, given time, to find out. Indeed in principle one can always discover that kind of answer if one searches for long enough. Let that assurance suffice. Now, come forward.

Hixten, grimacing in wry admission that he’d got the message, stood up. In this relatively bare landscape, on a world almost all water, a few principles stood out all the clearer. The sprinkling of genetic biota of ordinary material life was at a dead end, unable to progress far while the power lay elsewhere – in the giants’ open-ended natures, their own special fluidity, impossible to pin down with any scientific principle conceivable by man. And they had spoken their greeting with a flavour of certainty. They were convincingly, utterly sure that he would not be able to resist their request, or command, that he come to join them.

It annoyed him into defiance. He threw back a thought-ball:

All right, I’ll join you. It’s what I came to do anyhow – to join you in death.

That’s a bit of an exaggeration, the thought tumbled at him lightly, shaped in a laugh.

Hixton grimly strode on, not deigning to argue, and feeling exposed in the thin air, almost able to sense the curve of this little world. A third of the way towards the close horizon where the giants awaited him, he came to a bare stretch of plain where no clankers hopped. Here he was addressed in a firmer tone:

Stop where you are. You’re close enough. We simply wanted your mind undistracted, out of range of the little dense ones. But to approach us further might involve your human envelope in damage, to judge from what we’ve read in your brain, concerning what is about to happen.

Hixten thought back: You haven’t ‘read’ to much purpose, seeing as you’ve missed the main point. Death is what’s about to happen. Where we happen to stand won’t make any difference.

Ah, they replied with an easy ball, you forget that we cannot be killed; and neither can you, who are one of us.

“But just a moment,” Hixten said aloud, “you said, ‘Come and talk to us BEFORE THE END.’”

The end of our lives – you thought we meant? Not at all. The end of our edge-powers, maybe; the end of our present natures, yes; undoubtedly the end of all our explanations – but not the end of our SHAPES.

With that, they threw him their last ball.

Then it was that the count-down of seconds, tracked in Hixten’s subconscious, reached zero, so that the timer on Tethys unleashed the planned projectile, the oblong packet of force which he knew must dart across the space between the moons and smash onto Enceladus.

Between breaths, he waited. What of the impact? Tick went the seconds. The thing must have happened. It had happened yet he was still alive, with nothing to show for the cataclysm but a sense of some invisible sponge that brushed his awareness and wiped his view.

Hixten then understood that had over-estimated his kinship with the giant tree-shapes. One brutal instant and they were no more, whereas the same instant left him unscathed, for he was not a target shape.

They were gone, but what of that last ball of theirs? He figuratively scraped it up and opened its kindly translated message. The key word, homoplasy, was a mere recondite label, but the phenomenon itself coerced Hixten’s whole outlook; it clicked the hasp of his understanding so that he must admit what he now saw: the same sort of shapes as before.

The giants had told him the truth. They could not be killed. They could only be shifted, from mode to another, one nature to another. And -

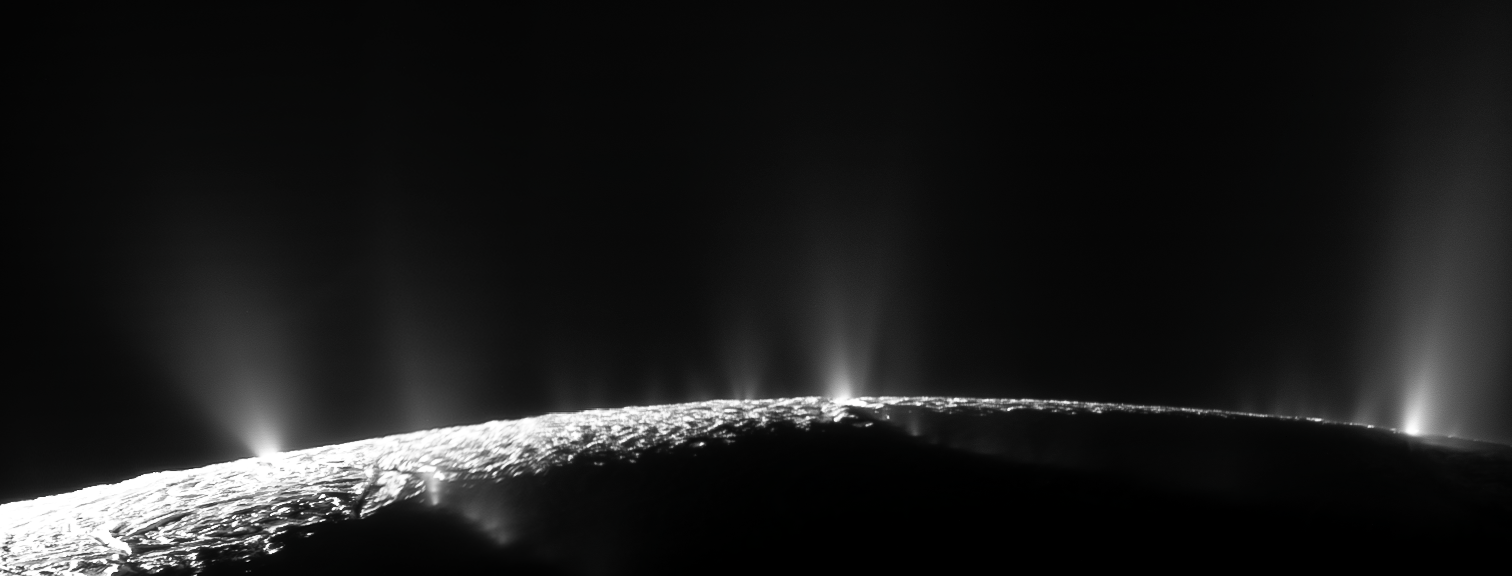

In place of the trees, the feathery tidal geysers of Enceladus spouted before and around him as though shouting:

Nobody can be killed!