greenery

a tale of the actinium era

from Uranian Gleams

by Robert gibsoN

1: The Welcome

Over the cork-textured plain, the crawler Uxtal was advancing at five miles per hour, with its hold full of cargo and its nomadic family crew.

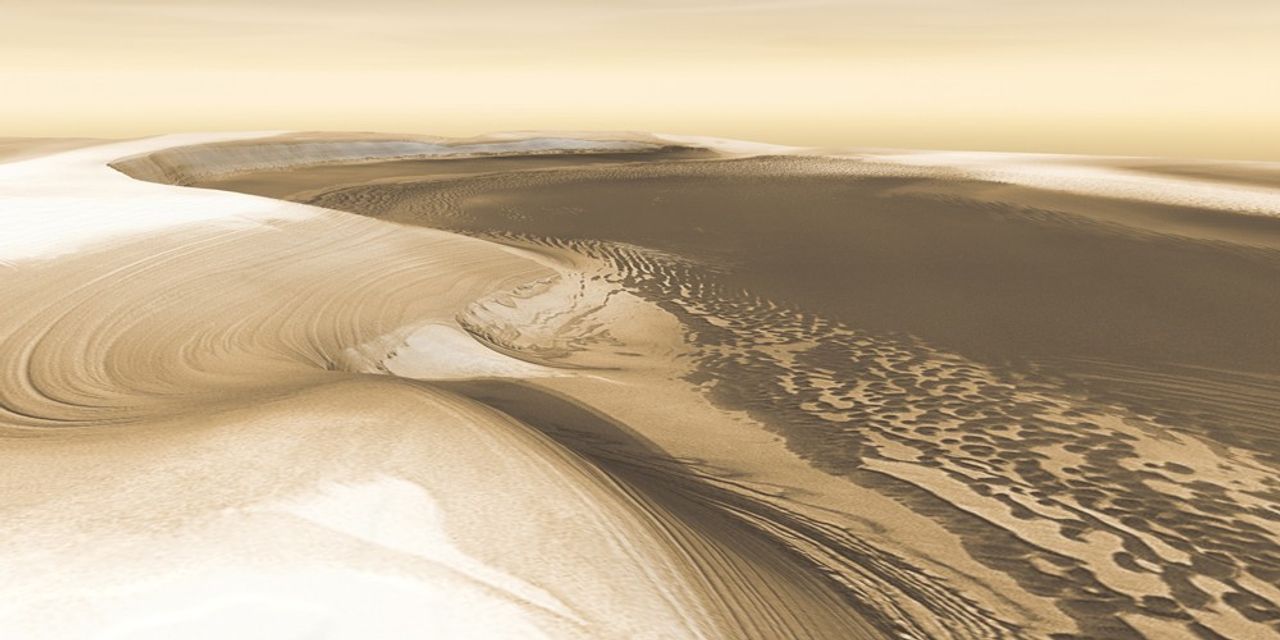

The great vehicle inevitably wobbled as the fortified superstructure, ten yards above the ground, swayed in the winds which blow eternally across the expanses of the giant planet Ooranye.

The three figures standing on the top deck kept their balance with unconscious skill though the powerful gusts changed direction with frequent violence. Father and son had been born on the plains, and the third figure, the new daughter-in-law, was likewise an experienced wayfarer. In their own eyes the Monray family were a component of the landscape.

Miokk Monray was in the prime of life, about 12,300 Uranian days old, while his son Gyan and Gyan’s wife Hevad were half his age. The black-bearded Miokk had the greyer skin, the more confident jaw, the slower, more decisive speech; Gyan, clean-shaven, had more the look of a poet or philosopher, combined with spurts of excited speech whenever his pent-up ideas gushed forth. He had the kind of courage which his father would never need: that of the lone revolutionary, perhaps the martyr.

Heedless of this ideological time-bomb Miokk overflowed with pride as he contemplated how well the youngsters had followed in his footsteps; or say, in Hevad’s case, the footsteps of tradition, which requires all young Uranians, whatever their station in life, to become adept at wilderness survival. At first he had feared that the girl might not fit into her new family’s mode of life. She came from Linnt, and the big cities bred some stay-at-home types. Nevertheless he had trusted that every Uranian, even the most urban, must sometime in nen’s life feel duty-bound to become a Wayfarer, risking nen’s life to feed data into the statistical maws of the cartographers of Syoom. In the case of Hevad, his trust had turned out well-founded.

Out of the corner of his eye Miokk assessed her for the twentieth time. The family could feel safely proud at the addition of a regal beauty with pale gold hair and gentle manner, a little reserved yet friendly to all; calm, capable, without the creative demons of discontent and personal ambition. Miokk repressed a sigh, which sprang from no particular cause, a vague reaction to life’s inherent melancholy, because the world was so large and people so small… He brought back his attention to what he was saying to his son:

“Just as well you didn’t seek my opinion prior to that exploit, Gyan. I would have told you that you’d never do it. Yet here you are. Seems we have a navigational genius in the family.”

The younger man, delighted at having won such praise from his father, could not repress a grin, though he managed a modest reply, “I had to justify the time I’d spent studying the subject.”

“Well, you’re undeniably pleased with yourself – with reason, I admit.”

The facts were creditable. Gyan and Hevad had set out during refelc, the starry morning twilight. After skimming for over two thousand miles, they had sighted Uxtal almost on the stroke of ayshine, that is, when the air, at its brightest, conveniently revealed the Crawler from many miles away. Indeed, a remarkable feat of navigation and timing. All that Gyan had had to help him fix the position and direction of Uxtal was information ten days old, relayed from a passing merchant convoy. (The Crawler emitted no homing signal, lest it attract foe as well as friend. For similar reasons, ordinary radio was used sparingly out on the plains.)

In other words without any up-to-date communications link Gyan had achieved rendezvous with a moving target after a ten-hour journey by skimmer. Impressed by this, Miokk felt encouraged to involve his son more closely in the family business henceforth.

So he began to discuss the current state of his affairs, confident that this was a strategic move in life’s endless contest of gain versus loss. He summarised the items of cargo currently in Uxtal’s hold (dried meats, seeds and nuts, some rare weeds and some Tungsten Era glass books), and listed the towns and cities to which they were destined.

Finally he got round to a more immediate topic:

“I’m particularly glad to have you back on board, Gyan, not only because of the splendid recruit you have brought us” (with a bow to Hevad), “but also due to that,” and he jerked his head at the forward-left horizon.

A thin line stretched across that hazy limit. It was, they knew, a structure, towards which Uxtal was crawling; an embankment without visible end, receding in both directions till it vanished into apparent infinity.

Without any doubt it had to be part of the ancient monoline network of Syoom. “Must be the Vlamanor-Yoon,” remarked Hevad. No one disagreed.

Seemingly immune to the ravages of time, the mighty Zinc Era network had left Syoom criss-crossed with embankments on which the empty rails still ran. Every few thousand miles, wayfarers were bound to cross one of these artificial ridges. On well-frequented routes this did not matter at all; however, grim experience had taught that any stretch of embankment which had not been visited for a thousand days or so must be approached gingerly. Preferably the approacher, be it a dray-master, raft-pilot or Crawler captain, should send scouts ahead to peer cautiously over the rim, before any attempt to get over with the main vehicle. And the more lasers on one’s side the better.

“Yes,” decided Miokk, “it must be the Vlamanor-Yoon. But I see no ramp.” No ramp, therefore no crossing. There was no way in which Uxtal could scale a sixty-degree slope. Again he took a telescope from his cloak-pouch. “Still don’t see it… We’ll scout this evening. After supper we can choose whether to go left or right.”

Hevad then performed an inexplicable, astonishing act. With the index finger of her right hand she pointed straight up into the air and said, “Maybe his girlfriend,” and she tossed her head at Gyan, “will tell us which way to go.”

Miokk blinked. Had he heard right? Bafflement snuffed any immediate response; he postponed the question.

Dinner that evening was held in Uxtal’s “stateroom”, a grandiloquent term for the family’s little haven of luxury, six yards by eight, lined with wood and metal banding, and lit by spherical corner lamps. It was a snug cave of comfort within a structure forever on the move. The shutters had been thrown back from the windows. The vehicle’s side-mirrors, moreover, had been extended so that the view ahead, including the approaching embankment, remained constantly visible to the diners.

Miokk Monray did not seriously consider any option other than to accept the challenge of the crossing. Uranian culture and etiquette demanded the meeting of challenges; the good of Syoom, the very definition of civilization required that those on the spot should venture forward. You had to dare to become a statistic, just one more in the eternal compilation of losses and gains, of deaths and survivals, without which the cartographers of Syoom could not do their work. The experience of hundreds of millions of days had shown that no other outlook was viable in the perpetual haze of distance and mystery on the enormous world, home not only to Man but to rival intelligences equally formidable. In this open-ended environment none but the mindless, statistical approach – percentages of safe arrivals, draughted onto maps as safety contours – might give quantity and shape to the unknowable, allowing humanity a chance.

Miokk knew enough history to realize that, from time to time, a different way had been tried. This other way was the attempt to understand the world. Useless foolishness. Failure was almost certain, and success, even if attained, was too dearly bought. A man who understood Ooranye was made vulnerable by his understanding. As the old saying went: if you get wise to the world, the world will get wise to you.

So, untroubled by the danger they must face at close of day, the Monray family chatted happily over their bowls. Zamena, the wife and mother, presided while the two younger children, Plenndwa and Traru, who had helped set out the banquet with artistic care, now sat listening to their elders’ plans. The children had decided to adore Hevad; they were delighted with her willingness to share their nomadic life – she was a treat which enlarged their universe.

“Of course,” Miokk had said to the newlyweds, “you will wish to purchase your own vehicle as soon as you can, but meanwhile there’s room for you on Uxtal.”

“Certainly,” Gyan had replied, “we’ll be happy to stay on Uxtal until we get rich or until Hevad yearns for city life again –”

She demanded, “What makes you think I might do that?”

“It’s in your blood. And maybe a bit of it in my head, too, by now. I’ve talked to Father this way before. He’s heard me say, often enough, that some day I shall take service under Ierax’s Noad. Or maybe, Linnt’s Noad.”

“Or how about,” ventured Miokk Monray, “the Noad of Noads?”

It was said almost slyly. Gyan studied his father’s face to gauge the seriousness of this remark.

“Yes, in fact I did go to Skyyon some few hundred days ago. To tell the truth, I felt so small there –” He chuckled, deprecatingly.

The older man remarked to Hevad, “Your husband is not usually as humble as this. I hope he is not in need of medical attention.”

“Don’t worry,” said the girl, “I am sure he’s simply waiting for the chance to make the Skyyonians sit up and listen.”

The silent Zamena, who doubted the wisdom of the way Miokk teased their boy, was relieved at the general laugh which followed. One day (she feared) Gyan might really shoot off in some drastic manner to measure himself against the world. Unless – and this was a hope – Hevad’s common sense could curb his restlessness. Thank goodness the girl seemed pleased with her new home.

Hevad was saying, “I like this slow, comfortable crawl… changes of scene but not too fast! All the advantages of adventure plus those of a solid home. Five miles per hour is just right for me. And the engine’s so powerful, you could add rooms aplenty to the vehicle and it would still go… in fact you could attach more engines until you ended up with a moving city…”

“Don’t talk about living in cities – even moving ones – to Father,” advised Gyan.

“No, let her speculate,” Miokk intervened. “She’s the cement we need.”

“Cement!” marvelled Gyan. “Pile on the flattery!”

“The myxe has flowed too freely,” reproved Zamena. Actually, though, the bottle was still three-quarters full. They were being careful. All of them remembered the crossing which loomed mere hours ahead…

“‘Cement’ is maybe a lucky nickname,” Hevad reassured them, “since we are about to attack a wall.”

Nobody responded. Hevad looked around. “Do I hear silence?”

Miokk Monray said quietly, “Don’t worry. We approve your attitude. We were simply uncertain as to how much you understood.”

“City-dwellers know how to share risks, quite as well as you do, I can promise that.”

“Good.” Miokk slapped the table and formally ended the meal with a welcoming speech for the new family member. Then he remembered he had meant to ask her the meaning of her cryptic allusion to Gyan’s up-in-the-sky “girl-friend”. When he could, he would put the question privately.

2: Battle at the Crossing

Uxtal lumbered on hour after hour. The Crawler left no trail; its brief “wake” – the impress of its tracks in the corky, granular gralm which carpeted the plains – sprang back elastically to level within a couple of minutes.

The loneliness and the emptiness of the Uranian plains is indeed oceanic, but just as a sea has islands, so does one meet with interruptions in the wilderness of Ooranye. One such was in prospect. The time was the middle of the eighteenth hour of the thirty-hour day and the monorail embankment was now a mere furlong distant.

Habitually during the eighteenth hour the family would gather on deck, taking the air at the beginning of evenshine. But not this day.

Everyone on Uxtal had retreated inside the vehicle. The windows were shuttered. Through forward slits, Miokk and Gyan scrutinised the ridge ahead.

The shape and dimensions of the embankment were standard. Height, seven yards. Slope, sixty degrees. Summit width, four yards. As for the length of this line, they knew it to be about five thousand miles.

What they did not know for sure was whether the as-yet unseen ramp, by which they must seek to cross, was to be found to the right or to the left of their location.

The decision was left to Miokk as he stood on the tiny command platform. He made up his mind and spun the helm clockwise; Uxtal’s front tracks veered to the right. Presently the great machine was crawling parallel to the embankment and about a hundred yards from it.

“I think we can dispense with the shutters,” he called out.

Gyan, who had been waiting in the doorway, was glad to obey. With clear windows once more, the crew peered forward into the beige evening light which shimmered upon the hard-pack surface of the ridge to their left. Up ahead a mile or so appeared a dark, woolly lump. Closer, it was revealed as a dense grove of thorny black katora. Growing close to the embankment, it reared its spikes to a twenty-foot height.

Gyan stirred and said, “I reckon the ramp may be just beyond that grove.”

“It’s often the way.”

“Shall I reconnoitre?”

“We shall. Remember our rule – always scout in pairs. Hear me?”

“Yes, father.”

“Now, call Zamena to take the wheel. While she’s about it, she can teach the controls to Hevad.”

From racks on Uxtal’s sides, Gyan and his father unclipped the canoe-shaped fliers. Bestriding them, the two scouts skimmed ahead of the Crawler. There was no question of going at full speed or of rising to the six-yard “ceiling”, the skimmer’s maximum altitude. On the contrary they hugged the ground. A mere yard above the gralm, they approached the grove at one-eighth speed.

Katora, in their long senescence, are a harmless plant species, but other, more dangerous relatives of theirs might well inhabit the grove. The sides of an embankment were apt to become the resting place for spores blown thousands of miles… Miokk, not altogether happily, allowed his son to outdistance him, for he knew that Gyan was the botanical expert.

Relief came as he heard the boy yell: “Look – I was right!”

Miokk floated over to where Gyan hovered on the far side of the grove. There, a ramp jutted at right angles from the embankment. It led up to the summit by a thirty-degree slope – a gradient which Uxtal could manage.

Making botanical conversation, Miokk remarked: “Quite likely, this is why the katora took root where it did – the ramp must have stopped the drifting spore.” A banal statement of the obvious, a polite attempt to show interest in a subject which enthused his son. And yet, surprisingly, the youngster objected:

“No! That’s not it – can’t be.”

“What do you mean, ‘can’t’?”

“I recognize this place now. Didn’t we go past it just over a thousand days ago? And the grove wasn’t there then, at all. And…”

“And katora take millions of days to grow from spores. All right. But are you sure we took this ramp, last time? Are you sure we didn’t take the next one along?”

Gyan shook his head. Meanwhile his father edged back from both embankment and ramp. Sighting the gradually approaching Crawler, he waved to indicate that he and his fellow scout were safe. Gyan continued grumbling, “Why ever build these monorails anyway? And if they had to be built, why trouble to raise them on these enormous embankments which must have taken man-eras to build? The rails could have been laid along the ground.”

The truth flashed upon Miokk. He ought to have guessed it before.

It was more than just the old habit of youth, of criticising their culture as if from an outside point of view.

“You’ve been talking to the Terrans.”

“Yes,” admitted Gyan proudly.

“I’m sure it must be a fascinating experience,” said Miokk.

Nettled by this polite irony, Gyan boasted on: “I have been accredited to talk with a Professor Linda Cummings, who has been doing her stint in orbit for the past fifty days. I feel I know her quite well.”

Miokk felt relieved that matters were no worse.

It was, after all, supposed to be an honour to be chosen as informant by the mysterious orbiting beings from the Sunward planet. Ever since First Contact a few lifetimes ago, the enigmatic Terrans – from a world so close to the Sun’s glare that it was hardly visible to Uranian astronomers – had given scope for endless speculation, but they aroused no significant resentments, and hardly any fears, while their eagerness for knowledge of Uranian history and life was taken by and large as a compliment. The situation, while puzzling, would continue to be acceptable so long as the visitors remained content to study Ooranye from orbit, refusing all invitations to land, and readily communicating in Ooranye’s own languages. While contact with an alien point of view might disturb some young minds, Gyan (in his father’s opinion) possessed a sufficiently robust intelligence to avoid being led astray.

He simply needed (like all chirpy youngsters) an occasional grounding in common sense.

“About the monorails, Gyan. Bear in mind that they were built in the Zinc Era. The people of that age knew they had thirty million days to play around in; they could afford such a project. And if it’s affordable, it does make sense: the height of the embankments give the drivers of the vleps a good defensive vantage. So the hugeness of it all is a helpful, practical advantage. And besides, the builders also hankered after glory…” It went without saying, Miokk assumed, that glory was a practical thing.

Gyan, however, turned his face away when the word was pronounced. Without deigning to reply he set his skimmer in motion and veered it round to the ramp’s other side… Miokk skimmed over to join him and they silently contemplated the few weeds which nestled there between embankment and ramp: plants so small as to be hardly noticeable compared to the giant katora of the near side.

“Ha!” Gyan pointed downwards, at a short post stuck in the gralm and bearing a notice:

Veann passed this way

11,151,596 Ac

No disturbance

Harlei Breal

Miokk, who found it only mildly interesting, sensed his son’s far greater absorption. One way to discover the reason was to bait the lad with an obtuse remark:

“Good old Harlei; this is the first I’ve heard of him since the last trade fair at Pjourth…”

“Now,” interrupted Gyan through clenched teeth.

His father looked blank.

“‘Now’ what?”

“Now we can stop pussyfooting around. Er- sorry,” snickered Gyan. “Earth slang.”

“Well, tell me what it means.”

“Messing about, is what I take it to mean. Now, though, we shall be able to cross without hesitation.” Jerking his skimmer into motion once more, Gyan flew onto the ramp itself.

A crowd of insights passed through Miokk’s mind as his son raced towards the summit of the ridge. According to the notice, the Wayfarer Harlei Breal had passed this way a mere 390 days ago. Gyan, influenced by Terran ideas, had probably picked up the quaint Terran belief that Nature was law-abiding; hence the lad would not believe that any weed could grow dangerous in 390 days.

Never in his life had Miokk moved so swiftly. His normal unhurried manner dropped away like a discarded cloak. He yanked his own skimmer into an angle of ascent which allowed him to cut into the ramp from the side. This was the only way to narrow Gyan’s lead. To fill one’s lungs and bellow a warning would do no good, Miokk knew; in fact it would steepen the odds against them, for it would use up energy better spent in drawing one’s laser –

Almost they reached the top together; almost as one, they saw beyond. As the sweep of the further plain met their eyes, so also did the rising clawlike leaves of a colossal narp, the deadliest weed to be found on the plains – the giant that could wait for lifetimes to perform its strike. And its root system, during the past few hours, must have heard Uxtal’s approach.

Intelligently, during that wait, the thing had drooped its leaves, but now the time for concealment was over and its spear-like points and jewel-tipped stems stretched abruptly higher than the ridge’s summit as the narp fired first at Gyan.

Miokk was never afterwards sure whether his own shot helped to deflect the vegetable laser’s aim. Perhaps indeed he could take credit for that, or perhaps Gyan with residual common sense shied at the last moment so that the dazzling bolt merely singed him as it hummed past.

A second shot from the plant impacted the bow compartment of Miokk’s skimmer and an instant later his half-blinded eye glimpsed an array of stems limbering up in what seemed like slow motion. He then understood, that what he and Gyan had experienced so far would be insignificant in comparison with the volley that was imminent. The two men reacted in the only way that could save their lives: they each cut the power of their skimmers.

Abandoning control was, in its way, a harder thing for a skilled rider to do than to face death. However, the alternative – to make a controlled evasive turn – required time which was not available. Their one chance was for man and vehicle to fall – to tumble helplessly back to safety on their own side of the sheltering ridge. Luck was with them and they escaped injury, sliding to the ridge’s base. Gyan slumped in his skimmer; Miokk rolled out of his, and stretched on the loam. Tough, fit Uranian bodies meant no bones broken, but they had to wait for their eyesight to recover.

Their muscles relaxed but their thoughts continued to slosh about like liquid in a suddenly stilled container.

“You idiot,” Miokk finally growled.

“‘Idiot’, no; just another statistic,” gasped Gyan.

A long pause.

“The statistics of Syoom,” grated Miokk wearily, “aren’t based upon cloud-brained actions.”

“Really?” said Gyan.

“I’d rather you weren’t insolent, son.”

“I’d rather you didn’t call me a cloud-brain, Father,” retorted Gyan with ego unbruised, sure of his ground. “Common sense told me that there should not have been a narp here. The thing had no business growing from spore to ten-yard monster within 390 days.”

“Spare me your Terran logic,” sighed Miokk. “Your Professor Cummings wouldn’t last a day down here.”

Gyan laughed shortly. “Well put, Father. But while you can growl in your beard all you like, I want something more. I want to understand.”

“But you also, I presume, want to live to be old?”

“Yes, if –”

“Then you’d better understand what the Terrans don’t get – that Nature can cheat.”

“Doesn’t make sense, what you’re saying.” Gyan’s exasperated tone had become almost a wail.

“Doesn’t have to make sense. All it has to do, is to happen.” It was Miokk’s turn to feel he had won his point. He waited for comment. None came. After a minute he added gently, “Our ancestors cheated too, remember.”

“Uh?” said Gyan.

“Think,” his father nudged. “Why does Syoom possess its twenty-five great cities, after all?”

No need to answer that one out loud. Everyone could dig into the guilty cultural memory of the Phosphorus Era. It was not possible to forget that the men of that time had looted another dimension of its power. Stolen power was what had enabled them to build the disc-on-stem platforms of ultimate metal which adorned Syoom; they could never have done it otherwise.

Miokk finished: “Come on, Gyan, save the revolution for another day. We meanwhile have to get Uxtal across the embankment and we won’t do it without a fight.”

The two men got back to their feet. They waved to Zamena, who by now was manoeuvring the Crawler around the katora grove. She must be guessing some of what had happened; the narp’s laser bolts must have been visible for miles.

Some distance further on she brought the vehicle to a halt, and the hold doors opened. Miokk on his crippled skimmer, and Gyan on his undamaged one, floated in through the opening.

Zamena yelled over her shoulder, “Either of you hurt?”

“Not a bit!” shouted Miokk. “Vital knowledge gained at expense of one dent in skimmer bow plus one fatherly lecture on philosophy of survival.”

The family gathered in the control cabin to discuss the next move.

Gyan spoke: “I wonder, do we have to fight our way over? Couldn’t we detour? Find the next ramp along?”

Puzzled anew by the erractic workings of his son’s mind – impetuous one moment, ultra-cautious the next – Miokk said evenly, “But that would just leave the narp as a problem for the next people to come this way.”

“We could leave a warning sign.”

“If everybody took that attitude, these routes would become impassable.”

Gyan grunted, “Let ’em become impassable.”

“That is an amazing thing to say.”

“The cities are self-sufficient. We traders are icing on the cake.”

“More Terran gibberish!” snapped Miokk. He softened his tone and smiled, “Get ready again to become a statistic, Gyan.”

During the next couple of minutes Uxtal moved in an arc which brought it to the foot of the ramp, ready to attempt the ascent. Meanwhile their enemy, no longer bothered with concealment, had extended its tallest stems. They wagged nightmarishly just beyond the ridge, like tips of warning fingers.

The thing was holding its fire till the Crawler had come closer. It was intelligent – how intelligent? Answer: as much as it needed to be.

One duty remained. Out of the door in the vehicle’s rear Miokk stepped one more time, bearing a post which he then hammered into the gralm. It carried a notice:

11,151,986 Ac

Uxtal

Narp beyond – full grown

Unless we win

Miokk Monray

He re-entered, took over the controls and the command of the projectile gun, and gave the word to advance. The Crawler’s treads were set in motion and it began to lurch up the ramp. Each adult member of the Monray family took nen’s place, laser-sponnd at the ready, at one of the forward embrasures.

The vehicle swayed forward as it topped the ridge, and bumped level.

Now it lay across the rail which ran along the summit.

At this height the enemy writhed in full view. A Terran might have described the narp as a Hydra-headed dandelion, magnified to tree size. Its laser-projecting buds promptly spat their whickering, incandescent bolts at the Crawler’s armoured front. With every thud of impact the temperature inside the vehicle went up, and Miokk had to decide whether to continue forward or to fight it out where they were; he decided to press on. Uxtal therefore again lurched forward, now downwards, to descend the far ramp directly into the barrage of laser fire.

Miokk pressed the stud of the projectile gun to send a ball ploughing into the loam among the plant’s stems, breaking some, damaging several more; he got in one other, more effective shot, but that was the gun’s last effort: with terrifying accuracy the narp replied with a laser bolt which entered the muzzle of Uxtal’s cannon and fused it into a useless knob.

Henceforth all the fire from Uxtal must come from its crew’s personal, hand-held lasers. These sponnds now had to be adjusted to fire staccato, in bolt mode.

One further weapon remained at Miokk’s disposal: the body of the Crawler itself. Reaching ground level, he drove the vehicle straight at the narp, intending to crush it entirely.

The battle was reduced to a race against time. Seconds would decide whether the plant could cook its opponent before being flattened by its advance.

In this situation, every hit from the Crawler’s sponnd-wielding crew had to be made to count, by destroying a stem or deflecting its aim. Miokk’s gaze was therefore riveted upon the streams of bolts from his own side, as he ground forward, but meanwhile he most feared the million-to-one enemy shot which might penetrate an embrasure. Victory seemed within his grasp as the narp tangled about him in its final throes; the outer leaves were already being crunched by the Crawler’s treads. Then his heart missed a beat as he heard boots behind him clattering down the spiral stair from superstructure to control room, just when one of the streams of fire from his side had ceased. News of tragedy? No, he corrected. Two faces of the same event. The person who had stopped firing was still alive, was the same one who was coming down from the upper deck. Out of the corner of his eye he saw without surprise that it was Gyan who had deserted his post. This was not the moment to demand an explanation. Miokk continued to steer Uxtal to its literally crushing victory.

Only when the impact of enemy bolts had ceased, and the contorting stems were reduced to the occasional feeble twitch as they lay broken on the gralm, did he halt the vehicle to allow it at last to cool.

Wiping sweat from his brow he went into the stateroom, to question his son. "Well?”

“You won, Father. You didn’t need my contribution any more.”

If I keep my tone mild, Miokk told himself, I shall learn more. “I ought to have been the judge of that –” he began.

He was interrupted by the others charging into the room. He did what was expected of him, hugging and congratulating them all, and in turn receiving their compliments and congratulations. Gyan partook of the mood insofar as he did not sulk, but as soon as the fervour had died down he said: “We need not have destroyed it. We could have gone the other way.”

Rather than intervene, thought Miokk, perhaps I’ll first let the others say what needs to be said.

He eyed young Trarv, who, sensing that he was being invited to comment, turned – nothing loath – to his elder brother with a “Why?”

And his sister Plendwa echoed him, adding, “We did well to clear it away, Gyan. It was a hazard.”

Gyan retorted, “Primly spoken, Plendwa! But meanwhile we have destroyed something unique. Never seen a specimen like that one.”

Judging his moment, Miokk nodded, “I dare say the narp was unique, but so are we, and so is each trade-lane across Syoom. Trade-lanes should not be allowed to die.”

“Father,” said Gyan, “I’m crushed flat by your logic. You win the debate as you won the battle.”

3: Surprise in the Night

Weary after their triumph, the family achieved only a few miles of further progress in the dimming air of late evenshine, and then stopped for an early night.

It was not always their practice to maintain a night watch. However, in consideration of the release of energies in the battle with the narp, they agreed that it was advisable to take the precaution, in case their laser emissions had been detected by anything within range.

Zamena took the first watch. After four hours she woke Gyan and went to bed.

Yyne is the darkest time of the Uranian night, when the aerial bneen have not only ceased to glow but have become opaque and pitch-black, blotting out the Sun and the stars. The lights were off in Uxtal too. This was a security requirement when out in the wilderness. Hevad, carrying a torch, came to wake Miokk and Zamena.

“Gyan has disappeared,” she told them. “He should have woken me for my watch, but I woke anyway, and found him gone.” Her voice was steady – toneless – desolate. Miokk felt the pit of his stomach slump, though on the surface of his mind he was merely angry.

To abandon a watch was unforgiveable. But then, suppose Gyan had fallen prey to nebulation? That mental disorder can happen to anyone, out on the plains. Even in the midst of company it can strike – though the soul is more likely to be overwhelmed when the person is alone. Gyan had been behaving peculiarly of late…

“Has he taken his skimmer?”

“I don’t know – I came straight to you.”

Miokk said kindly, “Let’s check that out first. Perhaps he hasn’t gone far.” But when they stood outside on the darkened gralm, a sweep with the torch showed them the empty rack on Uxtal’s side.

Miokk and Zamena hugged the quietly shivering Hevad and offered infinite sympathy, though they were in need of comfort themselves. Miokk remarked, “Admittedly, it’s going to be more difficult to find him since he’s taken his skimmer, but on the other hand I don’t fear for his mind as I would if he had wandered off on foot.”

Hevad said in a weary voice, “I know where he must have gone.”

“Tell us – and tell us why,” said Miokk, peering in vain through the dark at her unreadable face.

“Our destruction of the narp,” said Hevad, “filled him with remorse. He has listened to his Terran mentor Cummings about the need to preserve rare creatures. It’s a big idea on Earth, which I suppose you know is a small planet, its environments always fragile for some reason or other…”

“Earth influence,” muttered Miokk. “I knew it.”

“And,” continued the girl, “he mumbled something about going some day to the Sunnoad to appeal for help to protect endangered species –”

“If it’s not one thing it’s another,” snorted Miokk. “You just have to let them grow out of it. Got to wait for it to wear off.” This firm dismissiveness was his attempt to reassure the women.

Besides, the fact that his son had left them in the middle of the night, risking life and sanity, did not invalidate the brusque judgement, “nonsense is nonsense”, or so Miokk hoped. Endangered species – pah! What a lot of flunnd. The only plausible candidate for “endangered species” status on Ooranye was the human race.

4: Mission

A lone wayfarer may brave the wilderness for any one of countless reasons. Some skimmer-pilots bear messages across gaps in the radio relay system. Others sign up for data-gathering for a boss-cartographer. Some are merely curious about what may lie beyond a horizon; others are overcome by a restless urge or a craving for change for its own sake. Whatever the motive, once you start the journey, the experience can blur your consciousness, smudging, twisting your purpose. Especially at night.

The man on the skimmer, speeding polewards towards Skyoon over the everlasting windswept plain, found that the night encouraged him to forget his name and, almost, to forget his separate existence altogether and to become one with the darkness and the breeze. The darkness grew imperfect: flecks in the gralm raced below the keel as the air took on the slight and gradual visibility of pallyne, the prelude to morningshine.

He wondered what other voyagers had crossed this way; what invisible tracks, if any, history might have laid across this section of wilderness. Age, immensity, nuzzled him all around. The so-called “emptiness” thronged with possibilities as the air swished him with the hem of its robe of mystery. Above his head, low cloud-groups bumped into each other with little coughs of thunder. No space travel was necessary for the planet-bound denizens of Ooranye to meet the challenge of the void. They did not need to travel upwards to encounter ultimate loneliness. It stooped at them, pawing the surface of the sighing plains. The giant world was altogether soaked in space, girdled with engulfment. This quality invited the bravado of some wayfarers, the liberating awareness of others; either way, nature won over your sense of identity so that you slid into the daze of anonymity and personal insignificance.

Besides such dilution of the self, mature wayfarers can also experience an expansion of wisdom, a roaming objectivity that hefts the world and says, hmm, although it’s the only world I know, I shall never get too familiar; I shall always do it the honour of lifting my eyebrows in surprise.

This characteristic Uranian refusal to take things for granted can bring valuable insights, but on the other hand, the self being too small to have much effect, it can get to be too carefree, acquiring an irresponsibility… a detachment from life itself…

An experienced voyager must be on the alert for the delusions of nebulation.

Guard against this, the pilot warned himself. Focus on your gear, the reliable physical things which you have with you: your skimmer and your compass; torch, provisions, telescope, fuel-phials, maps: all stored in the bow-compartment – and of course your personal laser sponnd, engraved with your honorific initials. Furnished with all these, you’re a gritty, roaming cultural fleck, small and light as a particle of wind-blown dust yet firmly in touch with practical reality.

Thus the wayfarer used the texture of material things to keep himself mentally “grounded”. Inevitably, the result was to remind him of the home and family he had left. Consequently, a cry of conscience tore through the cave of his brain. Did I do right, to leave Uxtal? Is my mission a good one?

Perhaps it was trivial, perhaps it would turn out to be a waste of the Sunnoad’s time; in which case, he had distressed his family for no reason. If so, he did not deserve the luck which he needed to see him through. Don’t think about luck. Those horizons encircling him now: were they frowning, would the frown become a glare, and something condense out of it, and come at him, and make him into a drear statistic, one more wayfarer who set out for Skyyon and never made it? He shrugged; the hours went by. The air grew brighter, and he risked an increase in speed. Dangerous at night, a speed of two hundred miles per hour without lights is feasible during the day. He sped on, and his mood gained an exalted balance, steady as the velocity of the skimmer.

After seventeen hours of flight he sighted the first beads of brilliance on the horizon ahead, which announced the glowing fields of vheic in the cultivated region of Ammye. The sight brought down his distended awareness and furled the sails of his imagination, so that his self now scurried back into the anxious, limited body which bestrode the vehicle. Mind and flesh resumed their usual merger. The pilot took proper note of who he was.

And so Miokk Monray, following some hours behind his son, entered Skyyon’s realm.

5: The Thuzolyrs

On the last lap of the journey Miokk understood that he had come close to nebulation, but that the danger of this was now over. The likely end of the trip would bring him a new and different set of concerns.

Speeding past roads and farms, he gazed ahead impatiently now, in expectation of the city’s topmost towers. He could envisage no other course of action than the one he had chosen, though repeated reconsideration made his head throb... Even if he turned out to be wrong, it seemed best to get it over and done with. He had come this far; he would see the matter through.

Dots at long last appeared on the horizon ahead, rising as he approached: the moored skyships above the docking platforms of Skyyon. Next he was able to see the platforms themselves, and then, up-sliding into view, the summits of the highest towers. Meanwhile in other directions other skimmers could now be seen, many of them headed in the same direction as he. The scale of the city became apparent as the upper disc-tier rose into complete view, followed by the stem below it, then the lower disc-tier, and finally the base-stem.

By this time Skyyon towered above him and he was one with a stream of incoming traffic. The line of skimmers funnelled itself into a narrowing lane to converge upon the invisible elevator, the ayash current, which, some way ahead, was grasping the foremost city-bound travellers, fountaining them up from the plain. Miokk and his neighbours in the line soon began rising too, as their turn came to be gripped.

Though a nomad at heart, he never failed to thrill at the soaring entrance to a city. The best moment came when he was poised at the highest point of the aerial fountain, from which he could gaze down into the geometric glow of Skyyon’s heaped palaces and threaded walkways in all their mounded splendour. Then the drop began, and he must concentrate. The current poured him down towards the oalm or landing-plain on the rim of the city’s lower and larger disc. He kept his eyes down and his hand on his skimmer’s throttle, determined to make a good touch-down on the Polar City.

It was good enough, with no last-moment wobble. He stepped out, watching other arrivals to see where they stored their vehicles. Skimmer-banks were stacked to one side of the oalm, and he slid the canoe-shaped object into one of the available lockers, pocketing the key. (Absently he noted a small mirror-like shield, which hung at an angle from one end of the line of lockers. Something he should know about. He brushed the thought away. He was busy.) He walked a few yards to a rental where he hired a smaller skimmer more suitable for travel within a city. Here also he noticed one of the mirror-shield things. (Might be a scanning device, he thought. Doubtless placed there for security reasons. Again, he brushed the thought aside.)

His next step, he decided, must be to find some place to stay. He had no hope of getting an audience with the Sunnoad before quite a few days had passed. In fact, the more he thought about his mission the more he doubted his chances of obtaining a hearing at all. Out on the plains, in command of Uxtal, he was boss of all he surveyed, but here amid the teeming millions of the capital city of the Noad of Noads he was amazed at his own presumption…

For a start, he skimmed a few hundred yards down one of the radial avenues. Then he branched off into a side-street at random. Signs that promised visitors’ accommodation looked to be more plentiful here... but he noticed something that put his mind on a different tack. It was yet another of the reflective shields, hanging at the street corner. He knew what the thing had to be.

He parked the skimmer and approached on foot.

A perpetually replenished knot of people were standing close to the object, staring into its mirror surface. When he managed to get a good look, his skin prickled at the glossy patterns which swirled on the thought-sensitive surface.

Such psionic tricks were not to his taste. Oh for the simple life… he turned away. Never mind the search for lodgings. The sooner he was out of this place the better. He would make straight for the Sunnoad’s Palace. At least he could get on the waiting list for an audience with the Noad of Noads. Moreover, the fact that Gyan had preceded him was another reason to lose no more time…

Skyyon is two-tiered: its main stem supports not one but two discs – a structural feature unique among Uranian cities. The upper disc, smaller in radius, is reached by means of three interior ayash-airstreams rising from points spaced around the lower disc. So for the second time that day Miokk was fountained up and deposited upon a landing-plain – this time on the upper tier.

From the hub of this tier soared the flame-shaped, mountainous palace called the Zairm.

Miokk stood irresolute amidst the crowd of strolling sightseers in the Octagon which surrounded the Zairm. He felt futile. The multitude of thuzolyrs which hung from streetlamps and walkways irritated him. Why had the psionic mirrors been set out now? Were they simply in fashion? Wondering whom he might ask about the procedure for seeking audience with the Sunnoad, he peered at the entrances which radiated like tree-roots from the Zairm’s base. The biggest crowd was waiting around the nearest one. It did not look like a queue, but maybe they had numbered tickets so that they did not have to wait in a line. Or perhaps they had gathered to read what was written on the door. He approached that door – and before he could examine it, it slid open.

Simultaneously he was aware of a flash from a thuzolyr hanging on the wall nearby.

He turned, to meet the stares of the waiting crowd.

“Go on in,” said a man, a native Skyyonian from his accent. “What are you waiting for?”

With a clenching in his midriff, Miokk stepped into the Zairm.

At the end of the entrance corridor he saw another shield, flashing.

6: The Sunnoad

“Turn right,” said a faceless voice. It seemed to come from behind the shield.

He obeyed and walked on, towards the next wall-mounted thuzolyr.

“Turn left,” said another hidden voice.

Again he obeyed – and after this he saw no further flashing shield to aim for. Instead, a door opened, into a well-lit room, and in the doorway stood a man wearing a garment which made all the difference to how one saw the rest of him.

The man’s features would, perhaps, have been distinguished enough without it, but with it they were in a different class, for greatness was conferred, through inescapable suggestion, by the golden cloak around the fellow’s shoulders. Miokk became still. He was seeing Zednas Tremol 80520 in person.

“You wanted to see me,” said the Sunnoad.

“Yes…”

“Don’t stand in the doorway.”

Perspective came to Miokk’s aid. He told himself that if you added together all the people who had been given audience by this person, and all those who had spoken with his 80,519 predecessors, it would come to so many millions, that there was no particular reason why the name Miokk Monray should not be added to their number. Yet it was strange that he had got in so quickly.

After all, he had expected to spend days on the waiting-list. Nevertheless, come to think of it, he could imagine one reason for the speed of events. Often enough, when he had amused himself with the idle game of thinking, “What would I do if I were Sunnoad?”, he had pictured himself interviewing people summoned off the street at random… Some such fluky survey of public opinion might now be giving him his chance.

Beckoned in, he found himself standing on the floor of the Sunnoad’s office which turned out to be a small lounge with ordinary armchairs, low table and book-lined walls. Zednas Tremol sat and motioned Miokk to a chair opposite.

The light of a globe-lamp fell on the Sunnoad’s grizzled head. His moderately lined face, bidding farewell to middle age, possessed a heavy jaw, jutting chin and small twinkling eyes. The head was tilted as if keeping an eye on some message written on the ceiling... Miokk had to restrain himself from copying that tilt. Pull yourself together, he told himself.

Miokk said formally, “Thank you, Sunnoad Z-T, for seeing me. I wish to report, if I may, concerning the influence of the Terrans.”

The Sunnoad simply said, “Proceed.”

“I believe I have encountered,” Miokk spoke the syllables with great care, “a case of contamination - in the form of ideological transplantation.”

The Sunnoad gave the very slightest of nods, his very quietness seeming to show he was interested. Encourged by this, Miokk told the story of the fight with the narp, and of Gyan’s solicitude for the defeated weed.

“It looks to me,” he concluded, “like a case of idea-infection spread from Earth to Ooranye. My son’s words and actions, and his wife’s explanation of them, are what lead me to suspect this.”

"By 'contamination' and 'infection' I take it you mean, inappropriate transplantation."

“Yes, Sunnoad Z-T. Of course, there’s nothing wrong with Terran ideas in themselves – in Terran conditions.”

“Specifically, you mean you’re not easy about the Terran idea of preserving endangered species, applied to our world.”

“Well... it ought to concern us as part of a wider picture...”

“You are right about the wider picture,” said the Sunnoad. “The Terrans call it environmentalism. Their world is small compared with ours, its ecosystem fragile, vulnerable to the actions of man. So they have to care for their environment as if it were a delicate old grandmother. Your son appears to have absorbed this idea and is mis-applying it to our own more robust world. It’s a pity that he can’t instead be grateful for the privilege of living on a planet that can look after itself.”

“If Gyan is solely to blame, it is just a Monray family problem. But if the Terrans are playing some game –”

“No, I don’t think they are disturbing us intentionally,” opined the Sunnoad.

“In fact I have reason to believe that this is unlikely.”

The Sunnoad paused, and Miokk leaned forward in fascination, the hope strong within him, that the privilege of understanding was about to be shared. Zednas Tremol smiled at the nomad’s keen expression, and explained:

“One of the main points about our world that attracts them, that causes them to study it so avidly, is exactly that robustness to which I’ve alluded. The fact that we, its human population, can pit ourselves against the challenges of our environment without fear that we might damage it, is balm to the poor Terrans. They must wish that they could live on se strong a world. See what I’m getting at? So far from wishing ‘environmentalism’ onto us, they actually admire us for not needing it. The thought of Ooranye probably comforts them.”

“So they’re not trying to make trouble for us.” All that work to get here, Miokk thought, and it turns out I need not have bothered.

The Sunnoad replied indirectly:

“Having said what I’ve said, I ought to add that it’s doubtless true that their gut reactions to our scene remain inappropriate. Since they can’t really grasp what it’s like to live on a world where you can hunt, destroy, waste things and carelessly strive against Nature with the comfort of knowing that you will lose, they are likely to lead Gyan astray, and others like him, unintentionally.”

“A minor problem, then,” murmured Miokk. “Not some interplanetary plot after all.”

“Indeed not so bad as that.”

“I apologize for taking up your time, Sunnoad Z-T.” Miokk was abruptly aware of how much worse the meeting might have gone. He had achieved this once-in-a-lifetime interview and certainly it had not been a disaster. It had even reassured him.

Zednas Tremol meanwhile tilted his head further in responce to a hiss from a slot in the wall. A message capsule had just appeared. The Sunnoad reached for it, unrolled it… “This confirms that your son arrived safely a few hours before you did.”

“That’s good to know; I suppose he applied –”

“The thuzolyrs,” the Sunnoad interrupted. “They… speak to each other.” He added: “I have had them programmed with some… discretion. I expect you wondered why you were let in here so quickly.”

“I wondered,” agreed Miokk – sudden apprehension smearing coldness all over his back.

The Sunnoad continued, “It was for the same reason that Gyan was not let in.”

“I don’t understand, Sunnoad Z-T.”

“Oh, do you not? Then think. What use would I have for him? I leave run-of-the-mill revolutionaries and their stereotyped originality to be dealt with by my subordinates. Whereas…”

Miokk could not utter a word, such hoarseness clogged his throat. He could only listen as the kindly voice of the Noad of Noads thumped in his ears:

“…Whereas, I am on the look-out for the ultimate creativity…”

The words trampled on, flattening Miokk’s resistance so that his attempts to misunderstand got nowhere; he could not fail to see where they led –

“…the ultimate creativity, which is exhibited by those who possess the will to make something great out of things as they are.” He looked meaningly at Miokk, who still dared utter no word, not even a whisper. Zednas Tremol nodded to confirm, “I am telling you the real reason why you came here.”

“No,” he croaked.

“Yes,” the Sunnoad insisted. “It was, that you had obtained a glimpse.”

At last Miokk managed a more rational response.

“A glimpse… into what the Terrans are up to?”

Rational – yes. Plausible – no. Completely pointless, to pretend to misunderstand.

“Into what you shall be up to when I am gone,” grinned the implacable Zednas Tremol.

Woe to the pinned insect that is I, thought Miokk in a feverish extravagance of imagery which amounted to his last silliness, a denial that accomplished nothing.

“- You,” the Sunnoad continued, “who, if I mistake not, shall be the next wearer of this cloak. Don’t look so paralyzed; how do you think I felt when I learned I was next in line? Snap back, Miokk Monray; life and duty give us no choice. That should be a comfort. And don’t try to believe that the thuzolyrs can be wrong.”

Miokk now accepted, deep down, that he was in for it, yet he said inanely, “The thuzolyrs, or you, Sunnoad Z-T, must have made some idiotic mistake.”

“Who are you to pronounce on that?”

“I am nobody, and that’s the point.”

“Who is nobody?” shrugged the Sunnoad. “I have never met ‘nobody’.”

“I mean, I have no desire to be a Noad, let alone a Noad of Noads.”

“Another reason why you will make a good one.”

“But –”

“No reason to believe me today, or even tomorrow,” smiled Zednas Tremol. “Your hour will not come for a while yet – I hope!” But his smile was wasted.

“What shall I do?” whispered Miokk.

“Take your son back with you to Uxtal. Live your life, and wait. Ah, you’re looking more cheerful now – what’s occurred to you?”

“I was just thinking, if I haven’t dreamed all this, the day will come when my cheeky offspring does get his interview with the Sunnoad.”

“Don’t assume his cheekiness will end there. Even if it does, others will take up the task of correcting you.” Zednas Tremol spoke wryly now. “Believe me, I know.”

“Yes,” the nomad mused, “I have heard of Correctors.”

It did all seem like a dream: history come to life, his life. The great institutions of Syoom – thuzolyrs, Sunnoads, Correctors – converging upon his everyday thread.

His thoughts were echoed:

“So then, Miokk! You’ll be target practice for those geniuses who think they know best – and as a father you’re already part-beaded onto that thread, are you not? Now go back to your home for the time being. With luck, your next call here won’t be for many a hundred days.”

Miokk Monray strode to the door and then looked back, as if to make sure that he had really spoken with the golden-cloaked man. Yes, the sacred fabric was visible as ever, hunched about the sitting figure of Zednas Tremol. Miokk was nevertheless flooded with disbelief, sheer inability to credit the stupendous thing that had happened, and for some moments this mood of denial held him blearing from the doorway.

The Sunnoad without difficulty read his repulsion at the sheer improbability of it all...

“Now then, when you saw the elective mirrors all over town, what ought you to have told yourself, Miokk?”

“I ought,” he confessed, “to have said, aha…”

“Quite so," said Zednas Tremol, and supplied help with the words: "As in, 'aha, whomever the result alights upon will be surprised, and so it may alight upon me.’”

“Yes, but…” Miokk snickered desperately, “I could disappear.”

“You could try.” The Sunnoad bent his head, went back to his work.