io

[ + link to: What to see on Io ]

We're about to explore Io through the imaginations of pre-probe days. Let's look through the port-hole from afar, as the globe of Jupiter's inmost large moon gradually swells in view... Our eyes are now the eyes of the pioneers of the Old Solar System. We aren't really pilots, but we are the next best thing - imaginary voyagers: readers and critics.

Stid: A fun experiment, especially if we first consider, what sort of stuff do we expect to see?

by Frank R Paul

by Frank R PaulZendexor: A good question to ask - so that we'll soon be able to judge, if the tales match our expectations, that we've picked out some sensible themes for that world.

I know why you're suggesting this - you think it can't be done. You think we're doomed to fail if we try to pin down a standard or "mainstream" fictional Io. And the failure will rub in your usual point about how random and arbitrary and impossible-to-characterize is the fiction of the Galilean moons.

Well, let's see. In pre-probe days, what was known about Io?

Of the four large Jovian moons, Io orbits closest to Jupiter - just 217,000 miles above the cloud-tops of the giant planet. That's closer than the Moon is to the Earth.

Imagine, then, what it must be like to look at Jupiter from Io - you'd see, bulging in the sky, a disk well over forty times the apparent width of our Moon.

And that may be significant physically. Tides, you know, must be strong on Io - enormous stresses, causing heat and upheavals. This was later confirmed by images from space probes. But writers guessed it earlier.

What, then, would you expect from the fictional Io?

If it had no life-forms to startle, it would nevertheless harbour some sort of geological extreme... some specially amazing feature to challenge explorers. That's what Stanley Alston finds in Path of Darkness. A short character-versus-environment study, that tale brings Alston, a fussy little scientist, to confront dire peril.

...Weakly, he pulled himself onto a rock and sat down to still his trembling muscles and the nightmare shadows in his mind.

It was, perhaps, fifteen minutes before he raised his head to stare at the grey plain. What was it? How could it exist on this airless moon? It was inconceivable, and he stared at it in wonder.

Cautiously moving down to the edge of the plain, he put his hand into it. It was a fluid, certainly. His hand disappeared into it, and he could feel the viscosity of it. From where his hand had entered, little circles of waves moved away...

The true nature of the Ionian "sea" is all the more terrifying because Alston must cross it alone. It is a simple case of Man versus stark and lifeless Nature.

But now let us imagine a version of Io which does have life. What would be reasonable to expect?

Perhaps a world that developed rapidly, energetically. One whose culture blossomed early, like that of fictional Mars, and then declined. A world on which intelligence has degenerated, or is extinct.

And guess what, degenerated intelligence is just what ex-hunter Grant Calthorpe does find in the vivid 22-page tale The Mad Moon...

This wild little world was no sportsman's paradise, with its idiotic loonies and wicked, intelligent, tiny slinkers. There wasn't anything worth hunting on the feverish little moon, bathed in warmth by the giant Jupiter only a quarter million miles away...

Stid: The "slinkers" spoil your theory, Zendexor. They're not degenerated; they're on the up and up.

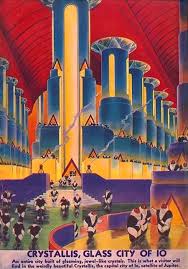

Harlei: On the level of a Frank R Paul city? "Crystallis, Glass City of Io", maybe?

Not quite within the ability-range of the slinkies of The Mad Moon - but I admit that if left alone, they may get there!

Grant comes across the "shoulder-high towers and battlements of a slinker village"

- a new one, for half-finished houses stood among the others, and hooded six-inch forms toiled over the stones.

There was a outcry of squeaks and gibberish. He backed away, but a dozen tiny darts whizzed about him. One stuck like a toothpick in his boot, but none, luckily, scratched his skin, for they were undoubtedly poisoned. He moved more quickly, but all around in the thick, fleshy grasses were rustlings, squeakings, and incomprehensible imprecations.

Grant later sets out to retrieve a thermometer which the creatures have stolen from his shack. (He needs it because his lady friend Lee Neilan has caught the local disease, "white fever".)

He has to approach the slinker settlement in darkness:

He paused in momentary surprise at the sight of the exquisite little town, a hundred feet away across the tiny square fields, with lights flickering in its hand-wide windows. He had not known that slinker culture included the use of lights, but there they were, tiny candles or perhaps diminutive oil lamps.

The slinkers pursue the Earthman back to his shack, and besiege the pair. Lee hears them raving.

"Ugh!" she said, listening to the tumult without. "I've always hated rats, but slinkers are worse. All the shrewdness and viciousness of rats plus the intelligence of devils."

...Grant peered out of the window. "...They've just passed from swearing to planning, and I wish I knew what. Some day, if this crazy planet ever becomes worth human occupation, there's going to be a showdown between humans and slinkers... They learn so quickly, and they breed like flies. Suppose they pick up the use of gas, or suppose they develop little rifles for their poisonous darts. That's possible, because they work in metals right now, and they know fire. That would put them practically on a par with man as far as offense goes, for what good are our giant cannons and rocket planes against six-inch slinkers?..."

Harlei: There's a lot more to the story than relations with the slinkers, so be careful not to over-emphasize just one aspect...

Stid: I'm quoting these bits so as to refute Zendexor's theory of Ionian decline.

Zendexor: It's not the slinkers, it's the loonies that support my thesis - only I hadn't got round to discussing them yet because there's so much to say about this story. Harlei is right: The Mad Moon gives us a richly imagined world, with plentiful imagery and a multiplicity of themes. There's even quite a lot of humour in it, successful humour, concerning the hallucinatory effects of the "white fever".

Now, as to the "loonies" -

These are idiotic balloon-headed creatures, whom Grant spends most of the story despising. In the end, though, he comes across a sight which changes his opinion:

A city lay there. For a brief instant Grant thought they had burst upon a vast slinker metropolis, but the merest glance showed otherwise. This was no city of medieval blocks, but a poem in marble, classical in beauty, and of human or near-human proportions. White columns, glorious arches, pure curving domes... It took a second look to discern that the city was dead, deserted, in ruins.

Lee points out the carvings:

...the figures, not of slinkers, but of - loonies! Exquisitely carved, smiling rather than grinning, and smiling somehow sadly, regretfully, pitiyingly -

So we learn that Io has not only a future (with the slinkies) but a glorious past (with the "loonies").

Moving on to the other classic Ionian tale, The Lotus Engine, we find that the little world has no future at all, only a past.

We've skipped from a lush Io to a desert Io - with an atmosphere too thin to breathe, a world where "not a real thing grew any more, except some rock lichens". The visiting Earthmen have to wear spacesuits.

The world used to be inhabited, but the "large-chested, furry, and goblinlike" Ionians had been "extinct for an inconceivable time - the victims of a water famine on their dying world".

The Earthmen are on the look-out for archaeological relics. They find a deserted city.

Its galleries and chambers had been dug out of the sullen, almost airless hills, by those final Ionians.

And they find an enigmatic "sun-engine" - a machine that runs on solar power - which looks as though it might still be in working order.

"We'll never have any peace until we see whether the engine'll run, Milt," old Russ had told me. And I knew he was right. Though later I was aware we should have left well enough alone.

So they start it up - not knowing what it is meant to do.

Stid: Well, go on with the cautionary tale. Tell us what macabre consequence follows from their foolish curiosity.

Zendexor: Before doing that, I want to remark upon the tonic casualness of this kind of tale. It's so free and easy! Here we have a small private team of two explorers busy crating native antiques on a Solar System world, because the opportunity's there, because stuff is lying around for the taking, just as adventure is there for the taking.

And I wonder: could there perhaps be some solar system, somewhere in the Galaxy, where this inspiringly loose scenario could be true? A solar system in which life arose not just on one of the worlds but on many of them, and space travel was achieved somehow without prohibitive expense, so that pioneering and exploration and encounters with alien life-forms were not only possible but were within the reach of private individuals.

Oh well, back to fiction.

The ancient Ionian "sun-engine" begins by making the Earthmen feel "tense and tight" inside.

I was thinking, somehow, of all the skeletons I'd seen on Io - and mummies, too. White-furred bodies, dehydrated and preserved by the dryness. Everywhere those old Ionians had died at their tasks... The conditions under which they had lived, in those final days, must have been terrible. Yet many of the mummies still wore eternal and mysteriously happy smiles on their withered faces. The Ionians seemed to have perished in joy. But why? How? In that question there was a blood-chilling enigma.

Soon, in the eyes of the men, mirages take form. The illusions which consoled the Ionians during their last days - visions of their world in its youth - reappear, due to the operation of the machine.

The narrator sees a lake "ruffled by little moving wavelets". An ornate city, a sky soft and blue, and many moons,

not almost airless moons like those of the present, for each was clad in the cloudy veil of an atmosphere.

And there was Jupiter... not streaked and cold any more. It glowed with a dusky, luminous redness, and it seemed that I could feel its warmth.

Then the vision begins to include people -

goblin people, very slender and pallid, and without the great lungs and chests of their descendants.

The more absorbing the vision, the greater the danger to the Earthmen in its thrall.

Some readers may spot an echo of this story in The Last Days of Shandakor, though in Brackett's tale the Martians who enjoy their illusion-machine are still alive.

An even closer parallel, in some ways, is Invaders of the Forbidden Moon by the same man who wrote The Lotus Engine, and written just about a year afterwards. Raymond Z Gallun's imagination, in its yen to return to Io, contributed to the accretion of its literary form. For though the details differ greatly between the two tales, they overlap in the theme of a dead race who tried to compensate by technical wizardry for the difficulties of their lot, and who came to a defeated end.

Parallels - overlaps - slowly but surely accumulate the literary character of a world.

Leigh Brackett, "The Last Days of Shandakor" (Startling Stories, April 1952); Raymond Z Gallun, "The Lotus-Engine" (Super Science Stories, March 1940); "Invaders of the Forbidden Moon" (Planet Stories, Summer 1941); M C Pease, "Path of Darkness" (Science Fiction Stories, March 1955); Stanley G Weinbaum, "The Mad Moon" (Astounding Stories, December 1935)

For the version of Io divided Cold-War style in Cyril Kornbluth's The Adventurer, see the

OSS Diary for 26th February 2017.

For Revolt on Io by Jack West see Space-Western Admixture. For climatic effects reaching up from Jupiter see Io and the Great Red Spot.

For The Mad Moon see Cunning Ionian Slinkers.

For the enclosed Io of The Copper-Clad World see the Diary entry, Ionian Gradations, and

the excerpt Beneath Io's Metal Roof.