the works of

jack vance: a flaw in the idea?

by

antolin gibson

My appetite for the writings of Jack Vance has waxed and waned over the years, and will probably go on doing so, but the wane has never been due to any flagging of the imaginative force of this writer. This has been sustained over so many wonderful novels and stories! No question of the ingenuity, and I would say lyricism in many of his creations of societies and alien environments upon worlds that are – because of the sheer astonishing detail – so very believable.

Nor has this occasional waning of my appetite anything do with the humour which, although somewhat formulaic overall, still tickles me, with all the howls of outrage the characters emit when thwarted, the disdainful fluttering of their fingers, exasperated pulling of their own noses and beards, bombast and wryness lovingly carried on from story to story, and some of the most sardonic and ironic dialogue of any genre. Indeed there is a character called Dordolio on the planet Tschai who pulls his own beard and nose so often in frustration that it is a wonder there is any beard or nose left, by the time we take our leave of him.

I do love all that.

Nor indeed has my problem to do with the horror so meticulously observed in depicting the Bad Guys and their efforts to bring doom and despondency. Nor (not to keep you in suspense much longer) is my problem to do with the comprehensive Idea, common to so many of his works, which is essentially an unyielding regard for Abstract Justice which, thanks to Vance’s imagination, spans the Cosmos.

No, none of all that – for all thus far seems to me pure genius and unequalled in the range and depth and detail of invention.

My problem is to do with the Good Guys.

I guess my faltering, when it comes to the heroes, is not a simple faltering and is in fact fairly complex . After all, they are mostly striving for Justice, for Right, for redress, sometimes there is even perhaps a hint of a striving for some mystical universal equilibrium. This Abstract Justice theme is usually expanded from personal experience, for instance, that of Kirth Gersen in the Demon Princes books. The Abstract Idea is only inculcated into him with the stern tutelage of his grandfather. Then Gersen becomes – really – like a machine, in his resolute exacting of revenge.

The same kind of expansion of the personal into the Idea is, to a greater or lesser extent, evident in many others of his works. Gastel Etzwane is another vivid example, in the Durdane Trilogy. Even the Dying Earth stories touch humorously upon the theme (notably The Eyes of the Overworld) and, less humorously, Vance’s other fantasy excursion, Lyonesse, especially Book Two.

But the problem comes when the Idea perverts the Character. That is, the “Good” character. When even righteous vengeance entails prolonged cruelty in the dispatching of villains, such as tying them to rocks so that they can gradually watch the incoming tide before they are drowned (Night Lamp), then Good becomes Evil, and alas sadism is viewed with a kind of dragging relish. As Tuco the Bandit says in The Good the Bad and the Ugly (which is not by Jack Vance, though in many ways it could have been!), when Tuco is apparently helpless in a bath and tormented by a man who intends to kills him: “Why not just shoot?” In this case, the tormentor’s cruelty backfired on the tormentor, as Tuco shoots first. But his question is apt.

And so - yes - I do confess to being disturbed by this side of Jack Vance’s writing, the torment inflicted not only by the Bad, but the Good. It crops up again and again. The prolonged punishment of Hildemar Dasce in Star King, the man in Araminta Station who must pedal to stay alive in front of spectators, and then sent to his doom upon some kind of whim to observe the suffering, and the long lingering punishment of the pirates in Trullion: Alastor, gaping from their torture-pens. It seems to be a streak of sadism in the many wonderful stories that – for me – because of the frequency and the ingenuity bestowed on these cruelties – appears to be an intrinsic stain that runs through much of the wonder and grandeur and freshness of Vance’s writing as well as being a flaw in his uniquely cosmic theme of Justice, which he returns to again and again, a theme which is noble, but which is thus marred.

Of course, there is horror and evil in the cosmos and where would Science Fiction be without it? Vance is probably being – cosmically – realistic.

But - the sadism in Vance’s works both from the “Bad Guys” and the “Good Guys” seems endemic in the very Idea of the striving for Justice, as though it is a necessary part in the striving, and thus the Idea is perverted, as it drives so many of the plots of Righteous Vengeance.

But!

Thank Goodness there is a “But” for me.

This vital “But” to a great extent explains the intermittent waxing betwixt the waning of my appetite for Vance’s works.

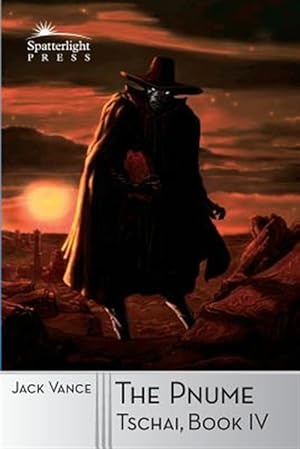

There is one beloved and faultless series which is not stained by the Flaw in the Idea. It is the Tschai tetralogy, otherwise called The Planet of Adventure series. But there is much more to the Tetralogy than adventure. There is the character of Adam Reith.

I think Vance goes far more deeply into this character than he does most of his other Good Guys.

Take some examples.

Adam Reith, in saving a girl, is reminded of when as a boy on Earth he rescued a cat from drowning. A stroke of genius by Vance. Thus now on a strange world, the hero so far from home, this flash of memory of Old Earth, this memory of a creature scared and utterly helpless! Superb. (Why doesn’t the author do this kind of thing more often?)

And Reith’s concern – his selfless concern - for the girl is developed so well, quite alien to many of Vance’s other heroes, whose ego and focused vision sometimes nearly rob them of their humanity, and make them more like machines. Adam Reith on the planet Tschai reins back from his preoccupations – his own ego - his drive to get on – to escape Tschai - by reflecting upon the problems of this girl (Zap 210), the trauma she was experiencing, in adapting to life upon the surface of the planet, after her life in the “Shelters” underground.

The whole of the fourth book – “The Pnume” - becomes for me a brilliant and sensitive parable of repression and then the coming to the light and the empathy of a hero towards someone vulnerable. It is very moving - and convincing.

Although untypical of Vance’s other writing.

Time and again Adam Reith holds back from his hunger for Justice, redress, even personal survival itself – because of his empathy for other peoples, creatures, cultures.

I wonder whether this depth of humanity of this particular hero does indeed explain the thought and subtlety and sensitivity for the world Tschai that the author shows? It is, I believe, by far the most brilliantly conceived of all his worlds and – thus straddling the four books – it is the only single world of Vance that has the true note of Epic. This is my view, quite possibly controversial amongst Vance-ites (of whom my brother is a notable connoisseur) and I promise to embark upon an (epic) rereading of Vance, and may well change my mind.

Jack Vance is usually a “polymorphic” writer as regards world-creations, he loves the many, hopping eagerly to the next, but on Tschai he is a “particularist” writer, lavishing his All on one particular creation, rather than on many worlds, and the detail and depth of this one world are extraordinary.

Perhaps Polymorphs therefore can be Particularists! But while conceding that Vance may have created other worlds on an epic scale, I’ll probably not shift from my feeling that Adam Reith – perhaps the most sympathetic of Vance’s heroes - through his highly sensitive perceptions of the world Tschai, lends greater depth to it.

And crucially, in a way, it is a happy epic, despite the terrible things that happen on Tschai! Adam Reith is sometimes intoxicated by the beauty of the world, in deep love with a girl he rescued, devoted to the friends he made (and often rescued, too, from perils).

Tschai is for me a happy epic for the simple reason that one can warm to the hero.

Oh, well, I just think it is nice, and good, and indeed helpful, if one can warm to a hero!

Comment from Zendexor:

The above has given me food for thought - rather hesitant thought, for my brother's argument comes as a surprise to me. Certainly the bad guys often get their comeuppance, but any cruelty involved is (as far as I can remember) not at the hands of the hero. The worst cruelties, those described in Trullion: Alastor, are definitely not approved by Glinnes Hulden, the viewpoint character. The punishment of Dasce in Star King is carried out by his erstwhile victim, Robin Rampold, not by Gersen. As for the rock-tying in Night Lamp and the pedalling-to-stay-alive in Araminta Station, these can't have made much impression on me, since I don't remember them! That may be because I have a callous streak which my brother lacks, but it may also mean that Vance wasn't really intending to rub in the importance of making bad guys suffer.

All that said, I must emphasize that we are both dyed-in-the-wool Vance fans, to such a degree that we often quote him in our daily lives.

Reply from Antolin Gibson, 24 October 2024:

But as the title of my article suggests, there is a flaw in the overall Idea – that is, the comprehensive viewpoint of the author that links so many of his books, which is his credo of Justice and Retribution. It is an Idea sometimes clearly defined and sometimes fairly vague and suggestive, but still pervasive. There seems herein a built-in theme in the Vancean Universe: which is sadism, not just from the “Baddies”. When I said that my problem was with the “Good Guys”, I meant two things: 1) that they are merely relatively good in that they stand back from this perversion, viz the overall Idea, and thus at times seem to condone it, and 2) that partly because of this they may become robotic and one-dimensional in their striving for vengeance and/or redress for injustice inflicted upon themselves. The author might well have called the overall Idea “equivalence” - indeed I seem to remember that he did use this phrase in this connection somewhere – in effect, sadism for sadism - Kirth Gersen stands back, endorses, this perversion in the case of Dasce - he does not inflict the torture himself.

I think in a way it might have been better if the long-drawn-out torture of Dasce had been carried out by Gersen personally because then one could more comfortably think of the “Flawed Hero” rather than the “Flawed Universe” - the perverse philosophy of the author. For this pervasive Idea of Vance does seem to me to be a kind of perversion. It brings the “waning” of my appetite, as I put it in my article. But as I also said, there does occur a “waxing” too. The wonderful detail, vivid otherness, everything one could wish for. I am probably in the position of C.S. Lewis towards H.G. Wells: Lewis said that he admired the story-telling, but not the philosophy of Wells.

Comment from Zendexor:

I see your point better now. I likewise admire the story-telling but not the philosophy. Where we differ is merely in the extent to which we notice the latter aspect; as a reader I am liable to be lulled by the skill of an author into overlooking the philosophy - except when it is overtly expressed, such as in Vance's explicit attacks on religion (rather like the shallow animadversions in the writings of Arthur C Clarke; in such "propagandistic" cases my critical faculties awake and I say to myself, Hey, I don't agree at all with this).

Another example of me being lulled is that it took me many decades to notice the sheer bleakness in the survival-of-the-fittest philosophy of John Wyndham, even though it's blatantly evident in all his novels except Trouble with Lichen. It takes a less ubane, far cruder approach to put my back up - e.g. the war on the "Bugs" in Starship Troopers. Even there, I hesitate to argue that Heinlein was totally wrong... easy to parody though the book is. (Pity it came too late for a Laurel and Hardy adaptation, "Starship Chumps".)

On the whole, I reckon my "lullability" (or gullability, if you prefer) has contributed to my enjoyment of reading - so even if I weren't too old to change, I'd probably choose to retain my nature as an easy subject for authorial hypnotism!

Reply from Antolin Gibson, 25th October 2024:

I would give much to have a natural resource in being “lulled” in this way. I guess I’m a bit the opposite, tending to get on a High Horse. Your parallel of Vance and Wyndham in connection with our theme is very perceptive: Wyndham’s apparent authorial endorsement of poor Sophie’s fate in The Chrysalids, by way of a ruthless doctrine of Evolutionary Advancement and Survival of the Fittest, is comparable to Vance’s endorsement of “Equivalence” which appears often in practice to involve extreme and prolonged sadism. I’m not so sure about what you say concerning religion, as regards the Vancean Universe. After all, when there is a discussion about religion – as Adam Reith sometimes engages in with his companions on Tschai – then it seems sensible, if incomplete, and not marred by an intolerant or mocking tone. I think what perhaps you are confusing with religion here, is Vance’s gleeful mockery of Cults which, bearing in mind the fertile place for such phenomena where the author lived upon Earth, were probably fairly much in view as he was writing his great books??

Comment by Zendexor:

Yes, to be honest I'd never thought of that: it could just be a dislike of Cults. On the other hand I suspect Vance might well have viewed Cults and Religion as synonymous - an all too frequent conclusion by otherwise powerful intellects which for various reasons are unwilling or unused to, or put off from, coping with the theme of qualitative transcendence.

>> Authors