neptunian allure

pioneers of the eighth planet in

wonder stories quarterly, 1930-2

Fortunately, although largely neglected in subsequent decades, Neptune did enjoy a lively little flurry of attention in the early 1930s.

Stid: Quite substantial attention, I'd say, given the coverage of that world in the works of Olaf Stapledon.

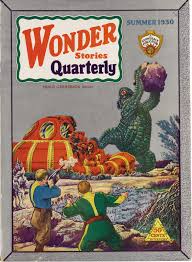

Neptunian king monster showing disdain for visiting spaceships

Neptunian king monster showing disdain for visiting spaceships

Harlei: Yes, yes, but what Zendexor means is, attention in the pulps. SF-magazine-type stories about Neptune as an exciting alien planet. Somewhere to visit and discover its native nature. We all know about Stapledon - but his Neptune, impressive though it is, is considerably terraformed, and inhabited solely by Terran humans or their modified and evolved descendants... Jolly interesting, I admit, but, well, there's a kind of "layer of concrete", figuratively speaking, between the Stapledonian Neptune and the one in the delightful Frank R Paul picture we see here.

Not surprising that picture has been so often reproduced! It thrills me - makes me want to jump up and down.

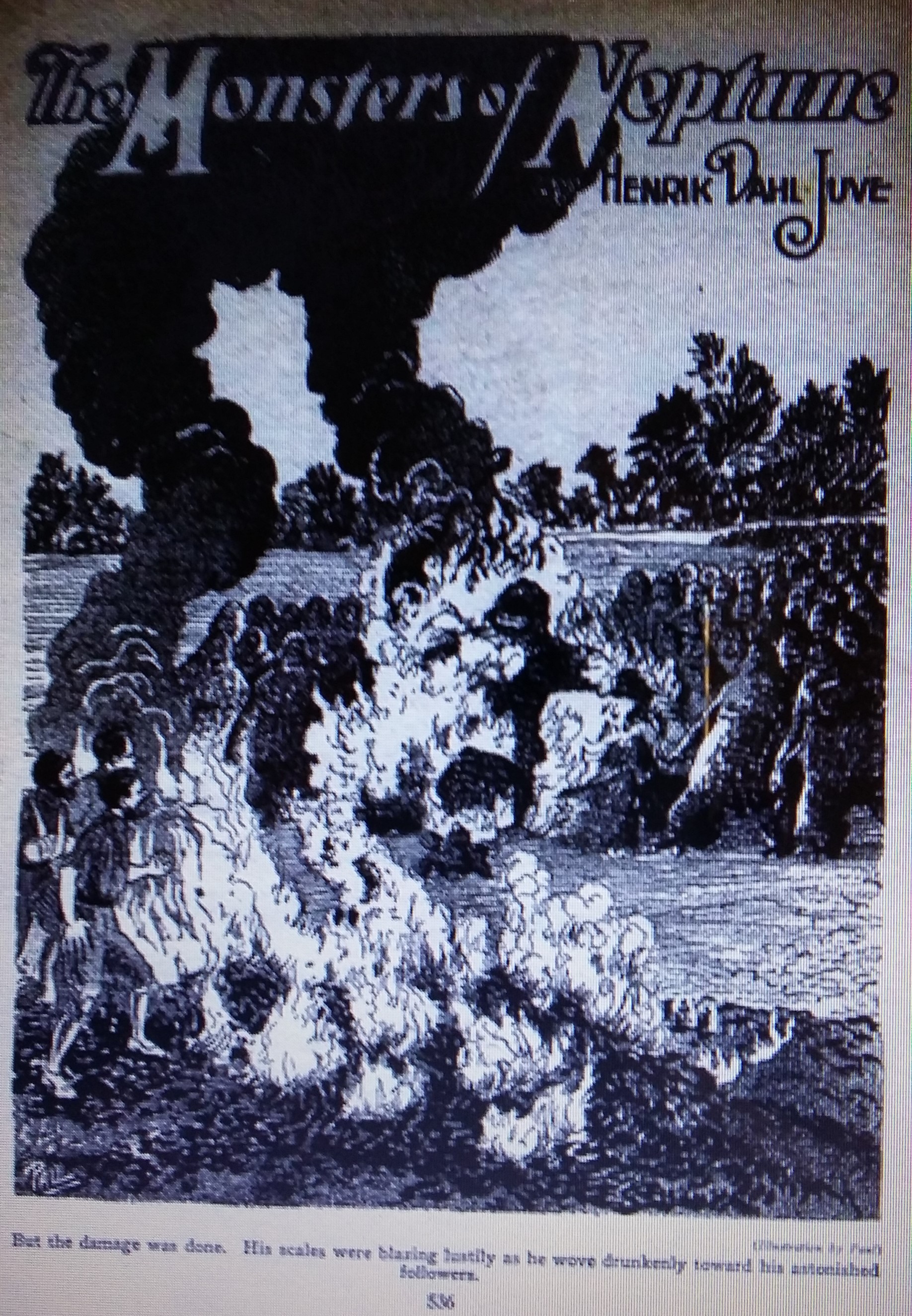

Zendexor: You'll jump up and down even more when you reflect that these early 1930s issues of Wonder Stories Quarterly are now displayed online, so that we can not only gawp at the pictures but also read the tales. Including this very one, The Monsters of Neptune. The thought of it turns me into a little boy again.

Stid: I foresee the trajectory of the argument on this page, Zendexor. You'll side with Harlei at first, and gawp at some more pictures, and then you'll proceed with mellow wisdom to admit that the tales can't possibly match the promises which the illustrations made to your young wide-eyed self.

measuring up?

Think I'm being cynical? You wait and see. You're really up against a law of spiritual nature here. Wordsworth in his greatest poem says it all. We come into this world "trailing clouds of glory" but the initial wonder then gets overlaid with ordinariness and eventually "fades into the light of common day". To elaborate on the Wordworthian analogy: the wondrous infancy is the magazine cover; the later come-down is the story inside. Sorry, chum, but you won't find what you're looking for in The Monsters of Neptune by Henrik Dahl Juve.

For a start, consider: who's ever heard of Henrik Dahl Juve? If his stuff was worth much, why wasn't it re-printed, anthologized; why hasn't his name echoed from the lips of devoted fans? Face it: it's pointless to delve in these newly-available online displays of old mags expecting that you'll come across an overlooked masterpiece on the genius scale of A Martian Odyssey. The choice nuggets have all been dug up; the seam worked over; the mine exhausted.

the monsters seem to have shrunk

the monsters seem to have shrunkZendexor: Your faith in the wisdom of editors and publishers, and indeed in that of the readership, is most touching, Stid old man. You ought to know better. Neglect of masterpieces, forgotten treasures, abound in the history of criticism, a history, may I add, which is ongoing: right now at this moment there are magnificent works which are languishing in almost total oblivion or, at least, not being given the attention they deserve - a category in which we can place Stapledon himself. You can't safely jump to any conclusions from the obscurity of Henrik Dahl Juve or of his contemporary venturer to Neptune, J M Walsh. It's like disbelieving in warmth because you happen to be living in an ice age, or vice versa.

However, this is not my line of defence here. Since it's high time I got onto the merits of the stories, listen to the following dialogue between father and son. The son, Dana Manson, wants to achieve the first ever successful landing on Neptune - the first to return and tell the tale. His dad, a transport tycoon, is appalled at the idea; he wants Dana to "take over the business; get married and settle down". But the rich youngster insists he wants to do something more adventurous. In fact he has to - his girl won't marry him if he doesn't.

"Terriana isn't the only girl in the world."

"For me she is."

For once the elder Manson fumed without reserve. Dana leaned against the window still gazing out. His handsome, bold features were clouded with thought. He ran his fingers through his reddish brown hair. Something of triumph stole into his eyes and he turned to his father.

"If I take over the business will you let me run it any way I please?" he asked.

The older man straightened and brightened. "Absolutely! I am glad to hear you are coming to your senses. You may run it with a high hand or run it into the rocks; you may divide it up among the employees or give it to the poor. I don't care how you run it and I'll not interfere. I'll sit back and watch your work and say nothing unless you come to me for information or advice."

"All right, I'll take charge right now."

Manson was elated. He called in the two vice-presidents and outlined the arrangement to them. Sour little Drisden, who had had his eye on the president's chair, looked positively ill, but Terriana's father, big, powerful Lozier, was hearty in his congratulations. He seemed more pleased than Manson himself.

"Now," said Dana, when the surprise and congratulations had subsided, "we'll carry on according to our present policy until I get back."

His indolence had dropped from him like a worn-out cloak and he had become a man of decision and force.

"Get back!" Manson almost shouted. "What do you mean?"

"From Neptune. I am in charge of this transport company now and I am going to Neptune to establish an outpost if there is anything there to warrant our extension."

Dutch holds the totemic jewel

Dutch holds the totemic jewelHarlei: Great beginning, impulsive, daring but not daft. Whets the appetite.

Zendexor: And written in a clear, zestful style. No sign of the dreaded clunkiness of some pulp-fiction prose. That's already a big plus. As you say, the tale begins well. Trouble is - and we'll have to be quick to admit this before Stid butts in to make the point himself - it's too dead easy to fan the outset of a tale with a breeze of open-ended promise and then stagnate as you run out of inspiration. Can the author maintain the vigour of the storyline, and can he keep us as excited when the hero has actually reached Neptune as we were when he decided to go there? Never an easy question, this. But don't lose hope, readers.

...Hour after hour they dropped through the clouds. They could not see more than a few inches beyond the windows so were afraid of striking something. Their descent was little faster than normal landing speed. They had gone through nearly four miles of fog when they noticed that the clouds began to thin. Dana reduced the speed still more and finally they were beneath the envelope and only five hundred feet above the ground. He locked the controls in neutral and the ship hung motionless in the air...

...A great jungle spread out below them. Huge, almost white trees struggled high into the air while tangles of thick, heavy vines tried to pull them back. Steam rose from the tangled mass and lost itself in the dank air... The whole scene was lighted by a weird, violet light slightly less brilliant than sunlight on the earth, yet brighter than moonlight...

Stid: Somewhat like a larger Venus.

Zendexor: Except for that special violet light which rises from the soil. To me, it's that which makes the world of The Monsters of Neptune and its sequel, The Struggle for Neptune, more than just another fecund Venus.

Stid: Come to think of it, most of the colour on Paul's front cover illustration belongs to the Earthmen's clothing and their vehicle. Otherwise the scene isn't all that colourful. Brown and violet ground, dark green monster (described in the story itself as violet-gray). Hmm... this just shows the power of associational thinking: I, even I, was dumb enough to fuse all the elements of the picture into a vision of Neptune itself as a colourful world, whereas in truth most of the scene's chromatic variety is imported from Earth. It just goes to show that, on occasion, I can be as big a mug as you guys are.

Zendexor: We can put a label on your associational fallacy and say you fell for "chromatic creep".

Harlei: A delusion which can't be blamed on the illustrator!

Stid: All right - it's a fair cop. But something I can blame on the illustrator, come to think of it, is that the monsters in the black-and-white drawing look much smaller than the one on the colourful cover.

Zendexor: Ah yes, the King Kong Effect: some monsters can fluctuate in size according to the artistic requirements of a scene. Rather than split hairs over that, I want to be positive. Be it noted, these monsters are not mere beasts. They have a language, and a peculiar superstition which the Earthmen manage to turn to their advantage, so as to effect a narrow escape from destruction, during adventures which contain quite a lot of suspense, though mostly narrated with some lightness of touch. There's some humour of a tense, semi-satiric kind especially in the desperate bluff which the ex-convict, Dutch, has to work on the Neptunians in order to stay alive in The Struggle for Neptune. "King" Dutch holds the red jewel which the monsters irrationally fear - but some of them are becoming ominously skeptical:

He had no weapons, but even if he had, they would have been ineffectual anyway. He realized that he was helpless to enforce his orders, for these two insurgents, either of whom could eat him without feeling overfed, were beginning to pierce the thin shell of his authority. He stuck the scepter upright in the ground and leaned back to think, but it was useless.

Meebroo was drawing closer! Experimentally, evidently. An overpowering desire to run and hide in the jungle asserted itself, and the king forgot everything but that hideous mouth and hungry eye...

The characters in these stories are very much private-enterprise risk-takers. Dana Manson is not exactly carefree but neither is he bound in the slightest by official discipline. Dutch, his loyal sidekick, is an ex-con who doesn't ask much of life - anything is better than being back "in the pen". The author's sometimes wry tone appropriately reflects this opportunistic approach to life. The style will also strike a chord in those of us OSS fans who fancy a Solar System in which we can mess around not only without oxygen flasks but also without too much officialdom.

dragons, plant-men, midgets and hyper-brains

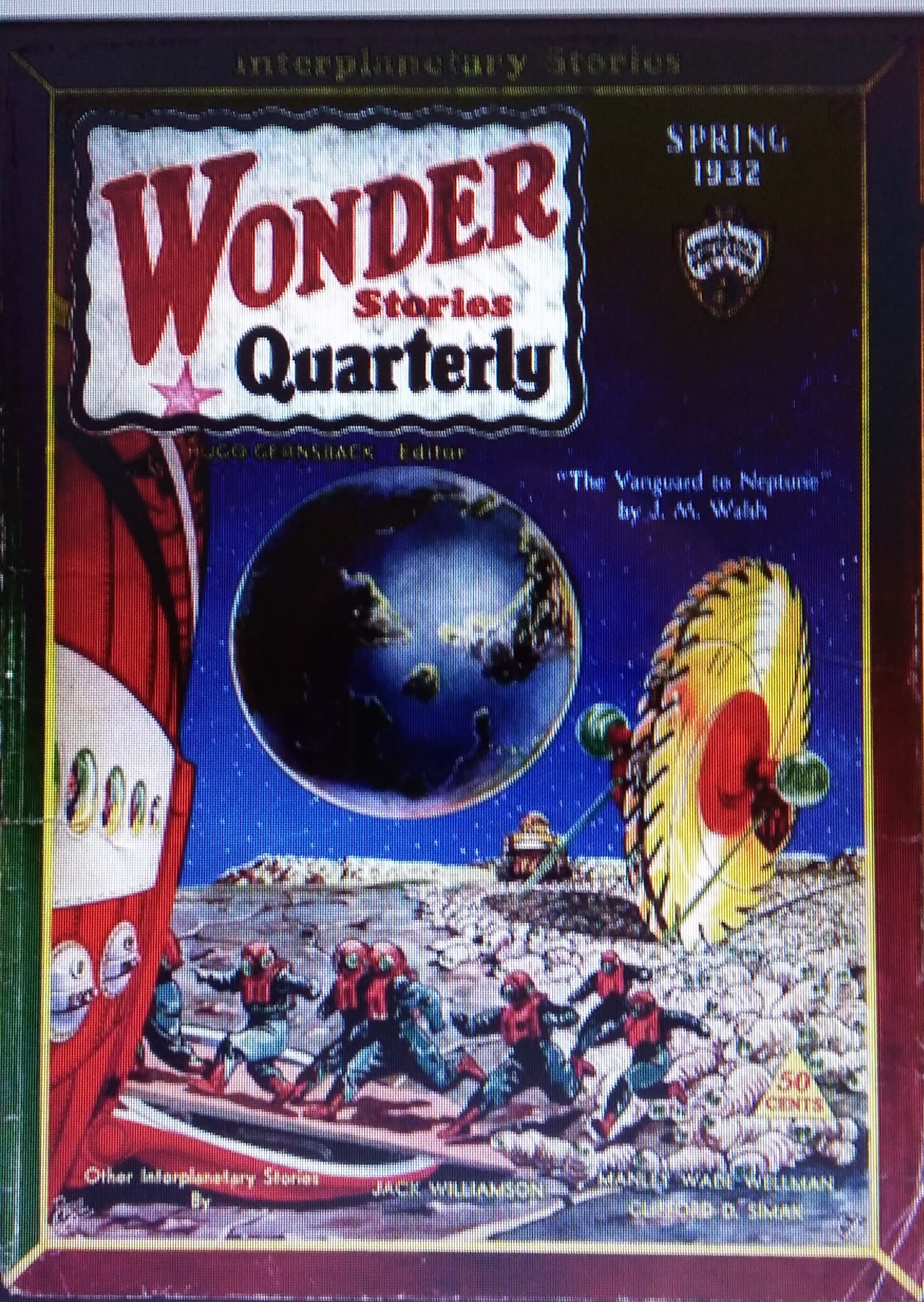

It's one thing after another in The Vanguard to Neptune, a far more officially planned adventure, comparatively solemn and heavy, and told in a more formal style, yet subject to a far greater number of crises, twists and turns - for which there is plenty of page-room, since it's a much longer story than the two Juve tales combined.

fleeing from Things on Triton

fleeing from Things on TritonWhereas The Monsters of Neptune and its sequel are told in the third person, The Vanguard to Neptune is a first-person narrative, an account by Philip Grayne, navigator on board the research vessel Icarus, on the first expedition to the eighth planet.

Plenty happens even before they get there - including a nasty brush with horrid things on Triton - but to give a flavour of the naif sententiousness of Phil Grayne, here's his account of the first effort to speak with humanoid Neptunians (by the way please note these aren't the only beings the explorers meet on that world):

...Whitby stepped forward, tapped himself on the breast and said, "Earthman," as slowly and distinctly as possible.

One of the Neptunians stirred, and made some sort of reply the very sound of which was absolutely unintelligible to us. Yet there must be some means of reaching a basis of common thought. They were reasoning and intelligent beings; they possessed apparently a civilization of sorts, and they had shown the ability to construct and operate intricate machines. Yet the sounds they uttered seemed to offer us no point of contact.

Stid: Typical foreigners. Why do they persist with their incomprehensible jabber? I suppose they just don't know any better.

first contact under the sky-mirrors

first contact under the sky-mirrorsZendexor: Before you dismiss Grayne as the "solemn ass" type, I want to make the point that in some ways his ponderous observations and plodding thought processes are an asset to the story. Even when they get boringly technical (which they do in one episode near the end), the effect helps to jog me into the make-believe mood that I am reading an official account of a real expedition, a piece of writing which would naturally comprise an uneven mixture of actions, impressions and wodges of heavy detail. If you're writing of a habitable Solar System, you're already demanding such a stretch of the reader's credulity that it's far, far better for your narrative to err on the side of seriousness than it is for it to skirt the lethal boundary of frothy lightness, for if you cross that, your tale straightaway dies of heart failure.

the flavour of neptune

It would have been a fantastic coincidence if the two authors we had discussed had given us the same vision of Neptune. On the other hand, on some level there is an urge in us readers to overlay one vision with another so that some sort of combination shimmers into existence.

Here's one way of making sense of the process:

Think of the complex personality of a human being, with his many moods. Then think of an OSS world as an analogous personality, each separate tale counting as one of its "moods".

Just as the whole person is the sum of his moods, the whole OSS planet is the sum of its portrayals.

Now, some of these portrayals are bound to have wider range and inventiveness than others. But even the most humble can contribute something to the collective iconography of the world in question - its literary gestalt. I see this begin to happen with the two stories discussed above. I'm hard put to it to map the process, and would welcome suggestions, but here, to make a start, is something which I think we can say exists in common between the native cultures of both versions of Neptune:

A certain defeatedness.

The Juve monsters and the Walsh humanoids are victims of different circumstances, but one feels, in both cases, that their giant native world is somehow too great for them to tame.

Henrik Dahl Juve, "The Monsters of Neptune" (Wonder Stories Quarterly, Summer 1930); "The Struggle for Neptune" (Wonder Stories Quarterly, Fall 1930); J M Walsh, "The Vanguard to Neptune" (Wonder Stories Quarterly, Spring 1932)

See the extracts, Looking around cautiously on Neptune and Yellow-violet jungle on Neptune.