the sunport vista:

zendexor's

oss

diary

2022

The Samuel Pepys of the OSS...

2022 December 17th:

JOHN WYNDHAM INTERVIEW

Nikita Zuev of the Roll Off A Tangent podcast team has sent me a youtube link that's worth a look. John Wyndham is being interviewed in a TV program in the year 1960. To watch it, click here.

I happily watched it for the pleasure of seeing and hearing that great writer for the first time. The questions asked him weren't those I would have chosen, but it was significant that he wasn't satisfied with the adjective "evil" as a description of the inimical forces which humanity faces so often in his novels. His bleak view, especially in The Kraken Wakes (which deals with an invasion from one of the gas-giant planets), was that it all boils down on both sides to "exterminate or be exterminated"; attempts at contact or accommodation would have been a waste of time even if they had been possible.

Having said that, I wish to emphasize that a Wyndham novel is a wonderfully urbane and civilized piece of writing, so much so that the philosophical bleakness escaped my attention for decades... I cheerfully go to an author as a willing subject goes to a hypnotist, in the belief that to be bamboozled is not to be conned but rather to get one's money's worth. It's the same - in a different mode - with Barsoom. The moral universe which the reader enters is not one which need earn one's approval when one is out of it.

(Am I then some sort of moral relativist? No, for two reasons. One is, I stress this applies to literature only - a form of imaginative magic that achieves what otherwise can't be done. The second reason: my moral stretching power has its limits even for literature. In particular I draw the line at having my stomach turned by contemporary mores.)

Meanwhile, readers, remember not to risk dying before you have sampled Wyndham's stories. Maybe don't bother too much with his early phase, but from The Day of the Triffids on, snatch 'em up.

Incidentally, in the interview Wyndham says at one point where he got the inspiration for the Triffids. That's perhaps the best moment!

2022 November 14th:

NEWS TRAVELS SLOWLY ON BARSOOM

Here is a short but revealing excerpt from volume ten of the Barsoom series, Llana of Gathol, in which Llana is relating the background to the story of her flight from the boorish Hin Abtol of Panar:

"...He said that he was Jeddak of Jeddaks of the North. My father said that he had thought that Talu held that title.

"'He did," replied Hin Abtol, "until conquered his country and made him my vassal. Now I am Jeddak of Jeddaks of the North..."

And that is all we hear of the defeat of Talu, whose rise to power is recorded in The Warlord of Mars, volume three of the series. (In volume ten there are numerous references to earlier parts of the Barsoom saga, suggesting that Burroughs was looking back affectionately over his past work, but he is not very systematic about it, and numerous loose ends remain scattered about, as they do in real life.)

What I wish to draw attention to here, in citing the defeat of Talu, is the way information of such importance is casually conveyed. I don't think there's any need to disbelieve Hin Abtol's claim; braggart though he is, I can well believe that he has conquered the rest of the North polar region of Mars. But look how the news is brought to the rest of the planet - via an off-the-cuff conversational boast!

Somewhere in the series, Burroughs' protagonist John Carter mentions with approval the fact that the Martians have no lawyers. To this one might add that they have no professional newsmen: there's no such thing as a Barsoomian reporter, and this also has its merits from the point of view of story.

Any critic who wishes to study how ERB succeeds in making a fairly small planet seem so big, will doubtless list factors such as: a sparse population; a land area covering the entire globe; political disunity; the many dangers inhibiting travel. To these points I suggest adding: the lack of any organized news services.

Am I then praising ERB for his cleverness here? Not so! He is reaping the reward, not of his ingenuity but of his instinctive world-building skill, his ability to dream, to tap some source far deeper than his very moderate intellect. Source-tapping is where his greatness is to be found. Reach a certain stage in that instinctive game, and you'll find your afterthoughts and your casual off-the-cuff bits of dialogue and explanation are apt to score jackpots which you aren't aware of. They slot into place, as we see from this example, in which Hin Abtol's boast sheds unintentional light on how the author of the tale makes a planet half the diameter of Earth into an inexhaustibly vast setting for tales of open-ended adventure.

2022 October 18th:

HISTORY OF HOPES - THE HUNT FOR VULCAN

Works of non-fiction have not figured very largely in the contents of this website. However, abundant material remains to be explored in old astronomy books and in secondary works on the history of astronomy.

Recently I purchased Thomas Levenson's The Hunt for Vulcan, and though I haven't finished it, I have read through the first part, which is all about the search for the infra-Mercurian planet from LeVerrier's announcement of its mathematical necessity in 1859, up until 1878, the year in which the idea received a fatal knock from the absence of any observed evidence during a total solar eclipse.

The rest of the book is about Einstein and how he put forth an alternative, relativistic explanation for the perturbations of Mercury's orbit. Interesting stuff, but not part of the OSS History of Hopes.

My stubborn mind cleaves to the possibility of an sf plot on the lines of John Greer's Out of the Chattering Planet (in Vintage Worlds 1), in which he speculates on how the old Mars as observed by Percival Lowell might be the true one after all, due to the Martians' reverse engineering of our space-probes. Or, come to that, my own Valeddom in which Mercury's old synchronous rotation is resurrected via the assumption of a different sort of interference.

How might this genre be adapted to Vulcan? One can of course simply bypass the authenticity question by assuming the reality of the planet, as is done in numerous tales, including those mentioned on this site's Vulcan page. But it would especially enhance a tale if its author could manage, in the story itself, to put forth an explanation for some kind of cross-over from our official reality to a Vulcan-inclusive reality - analogous to Greer's achievement in the title cited above.

My preference, from my reading of The Hunt for Vulcan, would be to start from the career of the book's most attractive character, a humble and obscure French country doctor named Edmond Modeste Lescarbault, a lifelong amateur astronomer who in 1859 believed he had spotted Vulcan transiting the Sun, and who later dared to invite the great LeVerrier to check his findings.

How might the plot develop? Could there have been two factions on Vulcan itself, one determined to allow their world to be seen, and another - who won out - who were determined to hide it?

Levenson tells us that Lescaubault died in 1894, ninety years old, locally honoured - the street where he kept his surgery is now named rue du Dr. Lescaubault - and generally forgotten.

Well, who knows who might have come to see him before the end, to reassure him that the secrecy had a reason... and that some day he would be vindicated?

The OSS is a great genre for stubborn refuseniks...

2022 October 5th:

MIDJOURNEY MARS

My failure to keep up with what's going on was emphasized the other day when Dylan Jeninga emailed me some excellent illustrations of OSS Mars - done with the aid of an AI! I was astonished, thus no doubt showing my age. Anyway, all credit where it's due, to whoever created the Midjourney AI and to Dylan for the choices he must have made when instructing it.

First image: a Martian canal which reminds me of an illustration by Chesley Bonestell; but this one has been engineered through more jagged terrain.

Second, one which reminds me more of the ruins of Yoh-Vombis in the Clark Ashton Smith horror-tale. You can imagine the parasites hidden in the tunnels...

Third, here is a more orthodox canal-scene; the Martian city is a bit Bradbury-esque but rather less fragile. More of a going concern.

2022 August 12th:

GIMME THOSE OLD-TIME DINOSAURS

A week ago Dylan Jeninga emailed me some ideas which got me thinking how appropriate it would be to use them here in the Diary.

To quote Dylan:

Lately, I've been reading about the history of paleontology, which in some ways mirrors the history of astronomy: it captured the public imagination early and resulted in stories and art featuring what we today know to be inaccurate science.

But like the OSS, I find those old dinosaurs still hold charms for me. The Crystal Palace sculptures are grossly off-base, but there's an appeal I can't explain. I think it has something to do with their history. Real dinosaurs are animals, those early dinos were monsters, imagined by the first paleontologists to live in a primeval world of chaos and violence (as detailed in works like The Book of the Great Sea Dragons).

Or maybe it's just the storyteller in me being unwilling to give up any toys. I like the modern dinos (Jurassic Park is one of my favorite movies) but I want the old dinos too - I want them all, just as I want Old Mars and Real Mars. I want to have stories about the lot.

I stumbled upon this piece of art (below), which really crystallized my feelings on the old dinosaurs. It's a recreation of the T-Rex escape scene from Jurassic Park, but with the Crystal Palace Megalosaurus. It imagines, perhaps, a world where the Crystal Palace Dinosaurs weren't statues at all, but living creatures (perhaps brought to London by a certain Professor Challenger). A Victorian Jurassic Park, with Old Dinos rampaging around London, would definitely excite!

My response to the insistence "I want them all" is to say: good for you; "I want them all" contains its own validation, because any true-life tale remains unfinished so long as anyone still wants something of it - our imaginations being agents in the creation of the final, ultimate Whole.

Dylan adds:

Dinosaur art has evolved dramatically since Mary Anning was digging up bones on the British coast, perhaps even more than space art has in some cases. I'm not sure what makes the greater change: the loss of the Martian canals, or the transformation of theropods from sluggish reptilian quadrupeds into active, feathered bipeds. Old art of the moon is still recognizably the Moon, regardless of the pointy peaks. Old art of Megalosaurus is unrecognizable!

It strikes me that the two might be joined: those old, reptilian, Crystal Palace dinos would be right at home on Old Venus. Something to get the mind turning.

...Lastly, darting to the other extreme from seeing dinosaurs as monsters, I refer you all to the eerily spellbinding Clifford Simak story, The Whistling Well (1980).

2022 July 17th:

WAYWARD AND DISORDERLY SPACE-ADVENTURE

Looking back at my Diary entry for 8th October 2016, written when I had just got part way through reading Philip Latham's Missing Men of Saturn, I feel the need to make further comment, now that I have read and recently re-read the book.

It's a peculiar book. A mixture of the unexpectedly good and the seriously disappointing.

It's sort of dipolar, the first part being interesting because of the development of the character of trainee astronaut Dale Sutton, who progresses from being an amusingly conceited popinjay to being a maturer young man subdued by events, and the second part concentrating on the quite different theme of the aliens on Saturn and the Terrans held prisoner there.

Those aliens are quite memorable but I found them disappointing. Other readers may disagree so I won't risk spoiling the story for them, in case they try the book.

The aspect of the story that strikes me most forcibly is the amazing lack of discipline on board the spaceship which brings the protagonists to Saturn. The behaviour of the captain and crew seems more appropriate to a teenage gang. At one point policy is even decided by a boxing duel between Captain Taggart and Dale Sutton. Distantly related to this rumbustiousness, perhaps, is the fact that no attempt had been made to re-visit Saturn since the first expedition a century previously. The Solar System culture in this book is certainly not subject to any systematic programme of exploration, and this ramshackle approach is worthy of note as a rather charming theme in much OSS literature. What could I call it?

Perhaps, the "Higgledy-Piggledy OSS" or HIPOSS...

The merit, of course, in this approach to story-telling is that it intensifies the breeze of freedom and of limitless possibility that blows through the tale. The less competent and disciplined you have to be, the more chance you have of joining in the adventure. Admittedly, Sutton has to graduate from the space academy, but though some technical skills are required, it certainly doesn't seem to lay much stress on psychological profiling.

2022 June 19th:

THE NAME OF A HORRID CREATURE

All writers must differ, but for me it seems natural to think of a name for a creature first and then extract the thing's attributes from its name.

But where, you may ask, do these names come from in the first place? (I ought to have discussed the question in An approach to world-building, but I find I haven't, much.) In some instances, the name is dredged up from the murky regions of my

subconscious, like the "gloggadoa" which makes its appearance in episode

14 of my Uranian saga; sometimes on the other hand it's more a blend of chance and deliberation, such as when a name crystallizes out of a chance mis-typing, or the sight of a promising-looking car numberplate.

Today the name g'foat came into my mind. From that term I extract the idea of some disgusting, smelly monster that lurks in abandoned towns on the Uranian plains. The way I discovered the existence of this creature is truly profound:

Most mornings I visit my local Tesco store and get things I've written on a list which I keep in my back pocket. This time I was puzzled to see I'd written the word "gfoats". After a moment or two of mental effort I realized that the etymology of this mysterious word sprang from the fact that my wife Mary is allergic to gluten and therefore makes her porridge with gluten-free oats, which we shorten to "gf oats". Written carelessly as "gfoats", it caused the concept of an alien creature to flash into my mind.

The moral of this anecdote is: never let a dopey double-take go to waste.

2022 June 8th:

AMBIVALENT MARS

Robert F Young's The First Mars Mission is a very short tale, which manages to squash an astonishing amount of thought-provoking incident into nine pages.

The story belongs both to the Old Solar System genre and to that of the New or Real Solar System. It is of unusually late date to be of the OSS; it appeared in the May 1979 issue of Fantasy and Science Fiction. On the other hand it could not have appeared much earlier, since it contains a mention of the Mariner and Viking missions, and the astronaut protagonist reaches a Mars which conforms to those space-probes' results: all very realistic.

However (spoiler alert) this astronaut finds, hidden in the rocks and dust, amazing physical proof that his child-dreams of Mars, in which the place was more like Barsoom, had also been real...

And he makes a decision. It would not have been my decision; in his place I would have done the opposite. I wonder what other readers may think, and would be interested to learn.

I can't do better than to quote from the contributor Lone Wolf, who brought the tale to my attention. He remarked to me in an email: "Curiously, it deals exactly with the theme we discussed before - about the ontological status of the Old Mars vs. the Realistic Mars and what is "reality" at all. It's a very short story, but it nails it..."

It certainly does. To read the story online, in the F&SF archive, click here.

2022 May 29th:

IRRESISTIBLE VULCAN

The contributor Lone Wolf drew my attention to the electric beings on Vulcan in Albert dePina and Henry Hasse's Alcatraz of the Starways (Planet Stories, May 1943), for the 203rd entry in Guess The World.

The tale does not only depict the buzzing "Blitzees". It also narrates an encounter with the much more intelligent and vaguely anthropoid native whom the Terrans rather unimaginatively call "Vulc":

…It was vaguely human in that it possessed a head, torso, four limbs of elephantine proportions, and it waddled upright. But the human resemblance went no further.

The creature’s skin, if skin it was, gleamed silvery metallic and gave the impression of being fluid! It reminded Mark of nothing so much as an immense blob of mercury that might at any moment collapse into a puddle and spread over the floor…

Vulc's food is metal; his Terran friends feed him on "powdered metal, filings and tiny scraps from the factories". This tough diet seems perfectly appropriate to me, on a world so close to the solar furnace!

And now for a literary recruitment drive. I feel there's a strong demand in the OSS canon for a novel set on Vulcan. A novel that does not merely having its climax there as does Edmond Hamilton's Outlaw World; a novel moreover which, unlike Hamilton's, does not relegate life to the interior of the little planet.

This ideal Vulcan novel would expand upon the cultural hints in Ray Cummings' The Flame Breathers (see this site's Vulcan page), combined with inspiration from promising elements in Leigh Brackett's Child of the Sun, Dylan Jeninga's The Winds of Vulcan and the above extract from Alcatraz of the Starways.

Most importantly, it would paint on the canvas of the reader's imagination a portrait of a civilization which manages to maintain depth and colour and variety despite being beleaguered by the harsh conditions on the little planet.

I imagine Vulcan would have to be a tiny world, maybe 800-1000 miles in diameter, with a sun-synchronous rotation like OSS Mercury, but also with a specially turbulent atmosphere which serves to extend the temperature and illumination of its habitable Twilight Belt quite a distance into the night side.

I would suggest that the habitable area of this world would be thinly dotted with city states, with much or little culture in common depending on their individual histories. (If I were writing the book the Vulcanians would be human telemorphs, like most of the Barsoomians and Amtorians.) Travel would be rare though not unknown; this would help keep for the reader a sense of it being world-sized and not just a one-horse asteroid. The protagonist might belong to an elite corps of professional travellers; the customs, philosophies and ethics of such people would be well worth the author's trouble to develop. The rarity of travel would increase its legendary prestige and also leave scope for a sense of discovery and of exploring the unknown - because the spaces in between the cities might harbour dramatic changes between one voyage and another.

A thread of mystery, to run through the book and shape the climax, might involve some legend of a solarian creature (see Child of the Sun), perhaps lurking in some cavern of fire wherein such a being might have been trapped for long ages, awaiting release. Its "Call of Cthulhu" style emission of dreams could be a theme in the book.

Be that as it may, the Vulcanians are bound to be saturated in legends based on physical phenomena such as fire, radiation, electricity, magnetism, molten metal and so forth. Stories set at either extreme end of the System provide extreme examples of the way in which planetary environments themselves become characters in OSS stories. Rich opportunities await the writer who sets out to exploit the possibilities of interplay between setting and plot in these spellbinding environments.

And there'd be good reason to assume that Vulcanians need not fear too much interference from Terrans:

…In silence they trudged mile after mile, following the same line of black hills that housed their Base. Mark marvelled at how comfortable the vacuum suits were, but he knew the real heat hadn't started yet.

It came presently, as they veered further outward from the hills. The heat increased steadily and became more intense than anything Mark had ever experienced. Perspiration dripped stickily within his suit. He wanted to wipe his face but couldn't; he could only shake his head to keep the sweat from his eyes.

But there was no keeping the mirages from his eyes. In every direction the terrain rocked and rolled under huge undulating hazes of heat. Horizons leaped at him in wave after wave, and fled away again. The men ahead seemed to do fantastic dances.

They no longer trod on rock. The ground beneath was soft, white and leprous looking, powdery almost as dust. Mark felt it hot around his metal-clad ankles. Now he realized the reason for the flat-bottomed sleds. He knew, too, that a spaceship could never venture over here and get back safely; compasses and magniplates and everything else would go haywire. Peering ahead, he discerned Vulc's fantastic bulk which now had turned a glowing cherry red! He shuddered at the thought of what would happen to a man suddenly bereft of the protecting vacuum suit...

So, folks, what are you all waiting for? Get cracking with your literary masterpieces...

2022 May 24th:

A THIRD LAND ON PERELANDRA

Two Venusian lands are portrayed in the novel Perelandra itself - the island referred to as the "Fixed Land", where it is forbidden to stay overnight, and the much larger land where Ransom ends up in the final chapters and which contains the "Hill of Life", Tai Harendrimar. But in the next and final volume of C S Lewis' Cosmic Trilogy we are told of a third land.

On page 337 of my Bodley Head hardback unabridged edition of That Hideous Strength, Ransom, speaking to Merlin, says:

"The ring of the King... is on Arthur's finger where he sits in the House of Kings in the cup-shaped land of Abhalljin, beyond the seas of Lur in Perelandra..."

Until recently I tended to assume that Abhalljin was another name for, or a name for a part of, the same land-mass that contains Tai Harendrimar, for that sacred mountain-top is also described as cup-shaped. But in my most recent re-reading I realized this was not so, when I compared the reference with the later one on page 458.

This time it is Dr Dimble, Ransom's scholarly associate, who provides the information:

"...There are people who have never died. We do not yet know why. We know a little more than we did about the How. There are many places in the universe - I mean, this same physical universe in which our planet moves - where an organism can last practically for ever. Where Arthur is, we know."

"Where?" said Camilla.

"In the Third Heaven, in Perelandra. In Aphallin, the distant island which the descendants of Tor and Tinidril will not find for a hundred centuries..."

It seems clear from the two references to where King Arthur is, that what Ransom calls Abhalljin when speaking in Latin is the same as what Dimble calls Aphallin when speaking in English.

Loving these books as I do, I enjoy, after the main reading, the piecing together of extra fragmentary references and clues. For example:

[1] The Sea of Lur is mentioned in Perelandra, page 194:

"...The King has not told you all. Maleldil drove him far away into a green sea where forests grow up from the bottom through the waves..."

"Its name is Lur," said the King.

[2] The "hundred centuries" mentioned by Dimble seem, from evidence in the earlier volume, to refer to Venusian rather than Terran centuries (the former being of course about two-thirds the length of the latter). We glean this from pages 195-6 of Perelandra.

Page 195: "...While this World goes about Arbol ten thousand times, we shall judge and hearted our people from this throne..."

Page 196: "...When the time is ripe for it and the ten thousand circlings are nearly at an end, we will tear the sky curtain and Deep Heaven shall become familiar to the eyes of our sons as the trees and the waves to ours."

Putting it all together, it looks like the tearing of the sky curtain and the discovery of Abhalljin/Aphallin will be more or less synchronous. That raises interesting questions...

The sense of mystery still permeates the great story, a huge, tantalising backdrop to the trilogy, in a fashion that reminds me of the way Tolkien ensures that Middle Earth is haunted by its past.

Lewis, however, also ensures that his trilogy is haunted by the future.

2022 May 16th:

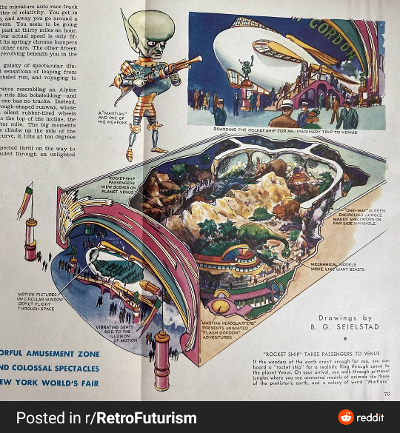

"VENUSIAN RIDE" AT THE 1939 WORLD'S FAIR

Dylan Jeninga has sent me an illustration of the above, commenting, "Apparently one would climb into a rocket and then journey to 'Venus' to see its jungles, dinosaurs and a budding Martian colony.

Would've loved to see it!" So would I. Here's the picture:

The fairground space-trip reminds me of Ray Bradbury's moving short tale The Rocket (to be found in The Illustrated Man), about a father who gives his children an unforgettable space-travelling experience that on a literal level is "merely" fake but on an emotional and spiritual level is real.

The 1939 World's Fair inspires poignant thoughts about how great futurity used to be. (I imagine the daydreams that might have gone through the mind of the later-to-be-great British sf author Eric Frank Russell, who crossed the Atlantic to attend that Fair.) The world was soon to be engulfed in war, which put paid to many dreams, while in a darkened tone it nevertheless gave rise to the technical marvels which soon made the space age come true. In 1930, Olaf Stapledon's future history Last And First Men had imagined that Man only got round to achieving space flight hundreds of millions of years in our future, when the imminent destruction of Earth made travel to other worlds imperative; yet the first man to walk on the Moon was born in the very year that book appeared...

2022 May 15th:

STUMBLING-POINTS IN PERELANDRA

“A crux is a textual passage that is corrupted to the point that it is difficult or impossible to interpret and resolve.”

So my online dictionary defines the word "crux", in its literary-critical sense.

A notorious example of such a crux in Hamlet is The dram of eale / Doth all the noble substance of a doubt / To his own scandal. It makes no sense as it stands, so we have to assume that something has gone wrong with that bit of text during its transmission from Shakespeare to us.

For some reason I am reminded of a couple of stumbling-blocks in the otherwise smooth flow of my thoughts as I read Perelandra. In the past few days, during a zillionth re-reading of that wonderful volume in C S Lewis' Cosmic Trilogy, I came across those difficult bits again and decided to share them with the readers of this Diary.

To be precise, there are three of these odd places in the book. I reckon that only the third one is possibly a "crux" in the sense defined above. The first two are - in my view - points where the problem lies in my own mind: I simply don't get what Lewis was trying to say. That's so unusual, given his usual clarity of expression and the sympathy between his views and mine, that I am reminded of the bafflements arising from textual corruption.

Now to give references to the three problem points. For the first one, I have put the key part in bold.

[1] Page 55:

“What are you talking about” said Ransom.

“I mean,” said she, “that in your world Maleldil first took Himself this form, the form of your race and mine.”

“You know that?” said Ransom sharply. Those who have had a dream which is very beautiful but from which, nevertheless, they have ardently desired to wake, will understand his sensations.

[2] Page 116:

“Hush,” said the Lady, “let us listen to the rain.” Then, after a moment, she added, “What was that? It was some beast I never heard before” – and indeed, there had been something very like a low growl close beside them.

“I do not know,” said the voice of Weston.

“I think I do,” said Ransom.

[3] Page 136

“Mercy,” he groaned; and then, “Lord, why not me?” But there was no answer.

[3] is, I suspect, a mere misprint of words which should have been “why me?” In support of this, one may cite the place on the next page which reads: He asked no longer ‘Why me?’

[2] (now that I think of it) might have a simple answer after all. The growl could have come from Weston's throat, the Devil in possession of him having been peeved at the Lady's interruption of his story-telling.

That leaves [1] and this is the important one for me.

I just cannot think up an explanation. If it's something to do with Ransom's difficulty with the way the old Malacandrian creatures are reduced in some sense to being "back numbers", I can only say that the connection between that idea and the actual words in this passage is completely obscure to me.

If anyone has any light to shed on this matter, I'd be interested to see it, the more so since it's so very, very rare that I have any difficulty with reading Lewis!

2022 April 22nd:

APPROACHING PLUTO

The following extract comes from the same tale as the recent entry 193 in the Guess The World series.

“…We’re falling rapidly toward the planet. I can only see half of it, filling the entire horizon. The color is almost exactly that of a pearl in moonlight, white with blue lights and absolutely featureless. Sunlight out here is indescribably weak. Our spectroscope, handled by Professor Reuter, shows the atmosphere is high in fluorine, with traces of argon, and outside that a thin belt, a very thin belt of helium and hydrogen… We have accurate temperature readings now, folks, and what they say is 200 degrees below zero, which is plenty chilly. You could drive a nail with a butter hammer at that temperature, folks, and it means we will have to do our exploring by diving, since the whole surface of the planet will be covered, perhaps miles deep, by liquid gases…"

It struck me that this sort of thing might do well in a page, or a series, concerning the approach trajectory to various worlds. I remember as particularly impressive the account of the approach to Mars in Rex Gordon's No Man Friday, in which the reader feels he's there with the apparently doomed pilot whose hurtling flight towards the Red Planet is "suicide on a grand scale".

It's the kind of experience which is most suited to the first ever voyage to another world.

What a shame that if humans ever do really go out and explore the System, it will all have been imaged beforehand!

Still, never mind the drawbacks of real life, at least we have literature...

2022 April 9th:

THE FROZEN GARDENS OF PLUTO

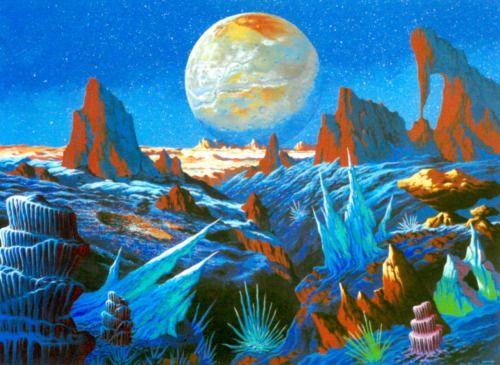

This is the name given to the following scene, the artist being Steve R Dodd:

(My thanks to Dylan Jeninga for sending me the picture.)

Does it show Plutonian life of a kind, or are the formations entirely due to the physical processes and effects of extreme cold? Or could some of them even be artificial structures?

(The example that comes to my mind when I consider how artificial some natural things look, is the so-called "Giant's Causeway" in Ireland. Geology certainly put on a magically misleading show there.)

If I were writing a tale based on the picture, I might be tempted to explore the life/non-life boundary, perhaps in an effort to envisage some third realm that is neither category as we know it.

Be that as it may, one might choose Pluto as an example of a world like our Moon whose "deadness" is very lively... full of personality, one might say.

2022 February 17th:

LATEST NUGGET FROM THE OSS GOLDMINE

It seems I'm unnecessarily pessimistic sometimes. For example I quite often rather gloomily reflect that I've read so much OSS literature from the great old days, that there can't be that much of it left to discover. Or even, that there can't be any...

That sombre mood has been lightened considerably during the past few days, during which I've been reading William F Temple's 1954 'juvenile' novel, Martin Magnus, Planet Rover.

I had purchased it in December 1995, second hand, for £1, and hadn't bothered to read it for the ensuing 26 years, simply allowing it to lie fallow on my bookshelf. It was a "just in case" purchase, without much hope that this garish paperback with the childish title would prove really worth reading.

How wrong I was! I ought to have guessed that it was likely to be good stuff, from the fact that it was by William F Temple, author of the marvellous Shoot at the Moon, which abounds in excellent characterisation and climaxes with a wonderful encounter of "borderline life". Yet when, a few days ago, I started to read the Martin Magnus book at last, it was not through any great expectation of enjoyment, but merely because I suspected it might contain material I could use on the Guess The World page. (And so it did - see entry 179 in the quiz.) The surprise it gave me was extremely pleasant.

The ingenious plot, which ranges from Earth to Moon to Venus, involves widely different intelligent species and an exceptionally well-drawn and original human protagonist. From the blurb ("Meet Martin Magnus, Space Investigator, who runs into trouble wherever he goes...") I had pictured a sort of Captain Future super-hero type. Not a bit of it. Magnus is an enigma to his superiors and colleagues. A troubleshooting spaceman with a superb success record, he's a Londoner whose only desire is to go home and live among his Bermondsey Cockney neighbours.

Another spaceman who visits his home remarks,

"...I expected to find the place a sort of museum - you know, chunks of lunar rock under glass... meteorites, rare Martian plants in pots, possibly genuine Martian sculptures, photos of spaceships, the Andromeda nebula, and sunrise over the Straight Wall - that sort of thing."

"That sort of thing," said Magnus, deliberately, "belongs anywhere but here. This is my home. Here I want to feel safe from that sort of thing. I don't even want to be reminded that it exists."

"If you hate that life, why ever did you go in for it?"

"You're the hundredth person who's asked that, and the answer isn't simple. I'll tell you some other time - maybe. Let's eat now. I always eat out here - I'm a wretched cook."

Later, as a concession to a colleague who had rescued him from a tight spot, he does confide the truth about his motives, explaining that although "the sight of the stars scares me green", he feels he owes it to the community that cared for him when he was orphaned, to "use my ability to the utmost to preserve life". That means troubleshooting on that dangerous frontier which he believes to be essential for humanity despite the fact that "anywhere outside of Bermondsey I'm always out of my element. I feel insecure, lonely, and scared. So to hide it, I have to act tough."

Not a stereotypical hero. But we the readers can enjoy the exotic scenes of his adventures even if he doesn't. I'm certainly tempted to hunt for the two sequels, Martin Magnus on Venus and Martin Magnus on Mars.

The more I think about 20th century sf, the more I feel inclined to label the 1950s and 1960s the true Golden Age. The sheer wonder and power of the human imagination in this connection is dazzling. What came before then was brilliant pioneering, but those decades saw a literary explosion in which authors roamed among the worlds as if they owned them - a staggering outburst of confident genius.

And I'm left to wonder how much of it I have still to find; what other gems may lurk in odd corners of second-hand bookshops, in garish paperback covers, with misleadingly simplistic blurbs.

2022 February 3rd:

AN ELECTRICAL MONSTER

A line maintenance man pleads with his boss to shut down Saskeega power station because of what has evolved in the wires.

"You can't just let it build, Stan. It's too bloody awful to think about. If this thing gets started..."

Mainwaring shook his head. "Rick, I'm in a vise. I'm caught in the same trap as everybody else. It's the sort of trap only the human race could have invented for itself. It could have sprung any time. It's chosen now. We're hooked on our own technology.

"Those lines have got to stay in. We need 'em. We're dead without them. Could be we're dead with them as well, that's just too bad. But we can't turn the clock back. We can't scrap electricity just because it's turned mean.

"I've told you what I know is true. But I didn't tell you I believed it. This is one of those times when knowing and believing are two different things. I can't let myself believe this because of what I am at Saskeega. I can't believe it on a personal basis either because it represents the descent to what I've been taught to regard as unreason. I can't take a fall like that."

The theme of being hooked on, or trapped in, technology, is

portrayed as powerfully, in the different context of nuclear power, by Heinlein in Blowups Happen. But in David Stringer's High Eight we see the even finer development of a related theme, that of the inability to "change mental gear" in time to adjust to dreadful knowledge (I'm reminded of Stephen King's Salem's Lot). Rick, the line maintenance man, knows he must get out, must get his family out, must snap out of his mental groove... but he is just too slow.

Rick drove up to his own place. Everything was quiet... he went and stood outside where he could see the valley, the mountain beyond, the lines moving up there like cobwebs miles away. He kept thinking he ought to be packing, they all ought to be getting out. But it was still too crazy. It was like throwing away job and future and home and all the folk you knew because one night you'd had a bad dream. It was all so peaceful. The air smelled good, there just couldn't be a Thing in the wires that was fixing to kill everybody on earth...

- David Stringer, High Eight, in New Writings in SF-4, ed. John Carnell (1965)

One encouraging thing about all this: we needn't feel we're lagging behind our neighbouring worlds in the monster-breeding business.

2022 January 27th:

A PLANET NAMED CHAOS

The Transplutonian planet which is the setting for The Eternal Machines by William Spencer (New Writings in SF - 2 (1964), ed. John Carnell) is a lifeless but vividly portrayed world, the junkyard of the Solar System.

...Robot ships shuttled in regularly from the more favoured planets of the system, bringing with them a capacity load of obsolete and unwanted junk of all kinds... The cast-offs from a machine-dominated culture... The dented detritus of the march of progress...

A warden named Rosco, an enthusiastic tinkerer with old machines, is the sole inhabitant. Rosco has just about the loneliest job in existence - and he likes it that way. He has created a special museum area:

...a clearing about two hundred yards square. Rosco had arranged, some time past, for the ground in this area to be left clear of junk. He had done so by the somewhat devious expedient of temporarily re-siting the sonic beacons which gave the dump trucks from the freighters their co-ordinates on the surface of the planet.

The cleared space had become Rosco's own private retreat. An oasis of order in the midst of piled-up disorder. Here he could pursue his obsession undisturbed.

With the loving care of a dedicated collector, he had reassembled some of the original machines from the dumps, salvaging a part here and joining a part there. In the inert atmosphere of the planet, these specimens of human technological equipment might last well over a million years...

The Eternal Machines is an unusual story, tragic yet undramatic, yet the food for thought which the author intends to offer us - a meditation on waste and obsolescence, on the nature of human heritage - is not what I intend to comment on here.

The aspect I wish to highlight is the character of the planet itself and what it tells us about the GAWI process in OSS literature.

You would expect, would you not, to find that the outermost planet in the System is deadly cold. Yet the coldness of Planet Chaos doesn't come through to the reader. Lonely it certainly is, desolate and lacking a breathable atmosphere, and these austere qualities imbue it with a mood quite fit for its location in the outermost reaches of the System. But all this just goes to demonstrate an unexpected principle at work, which I might put crudely thus: "if you follow some of the rules of realism, you are allowed to ignore the others". It would seem that once you've attained the minimum requirement, the pass mark of plausibility, you're home and dry. Applying that idea in this story, we might say: the author gives Planet Chaos so much of the feel of an outermost planet, he has banked so much in his plausibility-account, that he is sufficiently in credit for him to leave out the cold.

Heap it up with enough awesome desolation, loneliness and sterility, and you can have an OSS outermost planet that doesn't freeze you - instead, it numbs you by its isolation. Who needs physical cold when you can have metaphorical?