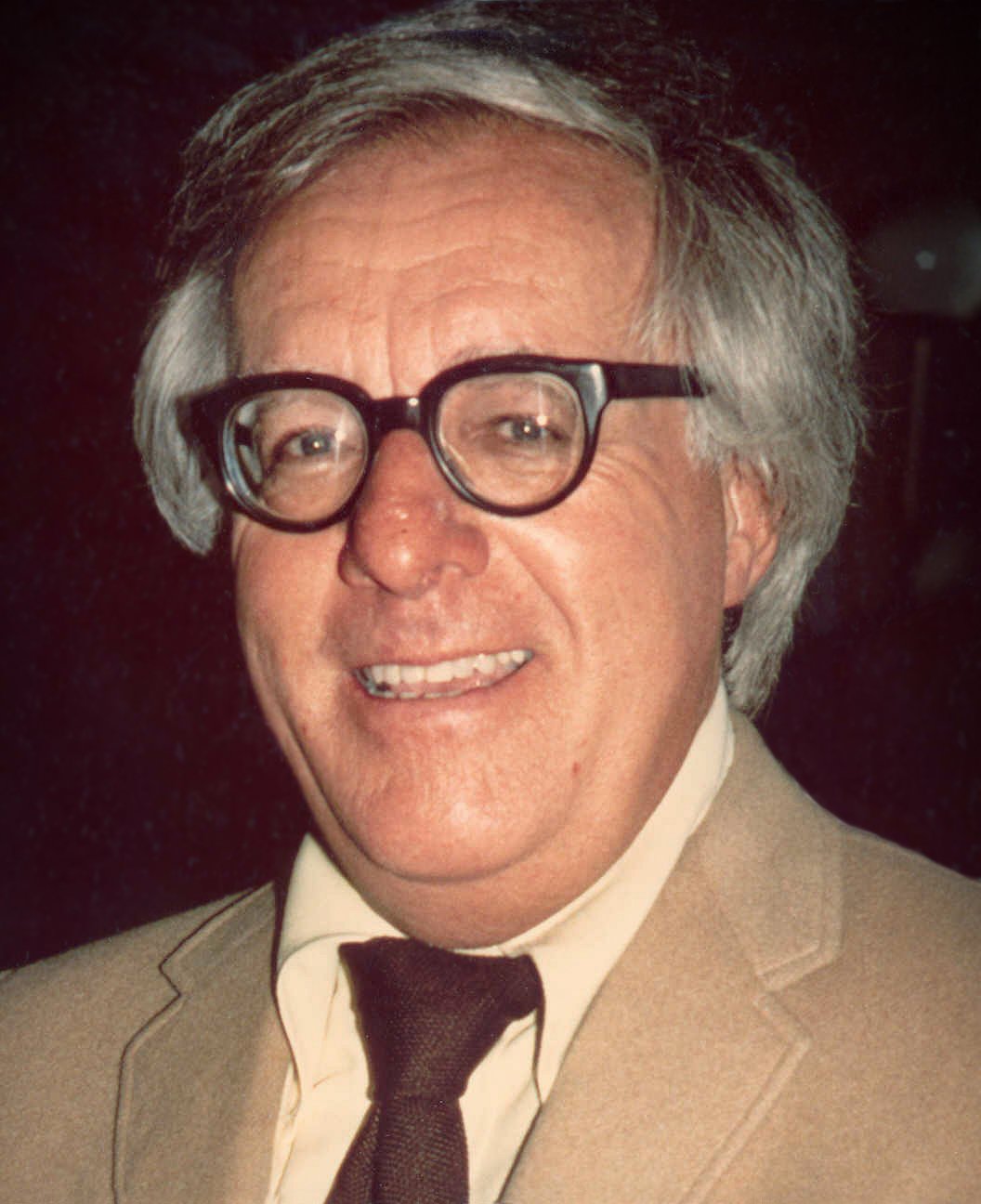

ray bradbury and the old solar system

The beauty of Bradbury's prose and the starkness of his ideas combine to make his writing both lush and lean at the same time. His Old Solar System hits the reader like a hallucination, lavish in the strength of its blaze, lean in its sparse solidity. Bradbury does not care a fig about how things work - only about what they mean.

On the Sun: The Golden Apples of the Sun.

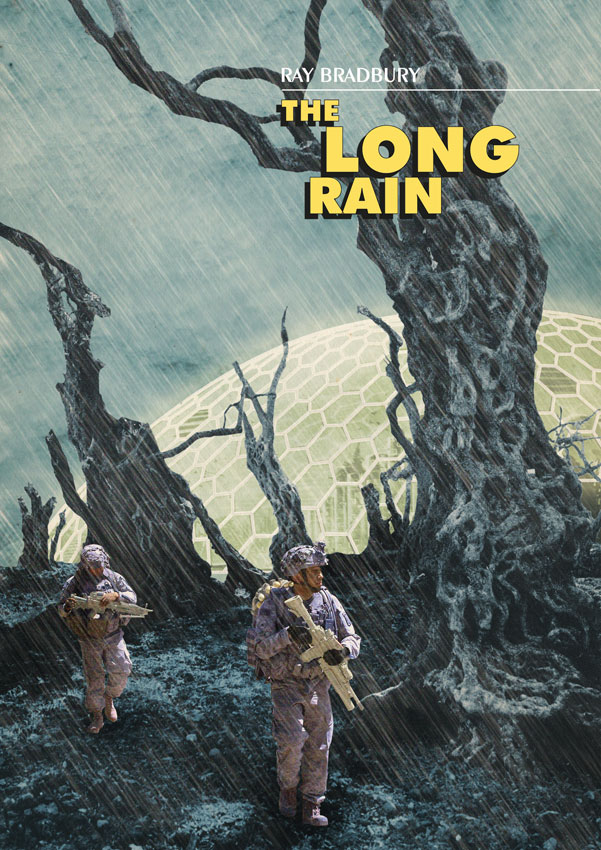

On Venus: The Long Rain.

On Mars: The Martian Chronicles; The Fire Balloons; The One Who Waits;

Dwellers in Silence; The Exiles.

Among the asteroids: Perchance to Dream.

Harlei: I want to say something about Bradbury but it's difficult to pin down in words the issue I want to raise -

Zendexor: Is it a negative criticism?

interplanetary culture clash

interplanetary culture clashHarlei: I'm not even sure about that! Look, the thing is, he's a stylist, a verbal charmer who in a sense seems to be playing a sort of tune in the reader's ear... playing some idea into the reader's mind... but there's something a bit thin about the performance... and yet his imagery is as vivid as imagery ever gets...

Zendexor: Let me help you out here. This is perhaps a good time to consider Dorothy Sayers' The Mind of the Maker, a work of literary criticism combined with theology. Sayers is one of those rare authors who can write excitingly about orthodoxy. She explains the point of the doctrine of the Trinity by linking it to the act of creation - showing us that any creator, human writers included, must possess in themselves, in their own nature, a kind of secular mortal Trinity, manifesting itself in the writer's art, as follows:

- the "Father", the controlling Idea of the work;

- the "Son", the fleshing-out of the work;

- the "Spirit", the interaction between work and reader.

And since perfection belongs to God alone, all human writings are to some extent "skewed" - "scalene triangles" Sayers calls them, in which the three aspects are not equally accomplished.

For instance, she cites the "cloudy cosmogonies" of William Blake as an example of a too-dominant "Father-centred" literary work; the over-lush poetry of Swinburne as an example of a too-dominant Son-centred one; and the emotion-swamped performance of some actor (I forget his name) as skewedly Spirit-centred.

You may not have any use for theology but Sayers' book certainly sheds some light on literature. It came to mind when I saw you struggling to express the "thinness" in Bradbury. I know just what you mean and I think of it this way: he's all Father and Spirit, with almost no Son. His ideas are powerful, and he communicates them to the reader via the incantatory magic of his style, but in the department of ordinary solidity, of sweaty lumpen-reality, he is not so good. So - he gets two out of three. I say this, just from having read his science-fiction; I have nothing to say about his other work.

Mind you, this "two out of three" judgement of mine leaves him safely in the category of great writer! And I don't even know if my comments are justified. For I have just thought of an exception to what I've said: the top-notch Venus story, The Long Rain.

Stid: I think you're completely mistaken anyway. You must be.

Here's Captain Bretton of the Copa de Oro nightmaring while his spaceship approaches the solar furnace in The Golden Apples of the Sun:

...while he worked he saw a future which was removed from them by the merest breath. He saw the skin peel from the rocket beehive, men thus revealed running, running, mouths shrieking, soundless. Space was a black mossed well where life drowned its roars and terrors. Scream a big scream, but space snuffed it out before it was half up your throat. Men scurried, ants in a flaming matchbox; the ship was dripping lava, gushing steam, nothing!

"Captain?"

The nightmare flicked away...

...When it came, it'd be the quickest death in the history of dying. One moment, yelling; a warm flash later only the billion billion tons of space-fire would whisper, unheard, in space. Popped like strawberries in a furnace, while their thoughts lingered on the scorched air a long breath after their bodies were charred roast and fluorescent gas.

Can you call this writing non-sensuous, Zendexor?

Zendexor: No, but it's kind of headlong, isn't it? It doesn't leave you to roam at your own pace. That may be what I was trying to convey when bringing up Sayers' categorization of authors' abilities. Bradbury has the ability to impose a controlling idea, a controlling mood, to a more powerful degree than most writers. And quite often the controlling idea is so strong, you aren't allowed one single roaming moment of your own - you aren't allowed to forget the message (for example) that Man is bound to mess up the civilization of Mars, or bound to bite off more than he can chew in trying to conquer Space.

Stid: Though actually it appears that Man does get away with a successful mission to the Sun, no less!

Zendexor: All right, you win that point. Let me also concede - as I was about to do earlier on - that in The Long Rain Bradbury does give us a pure adventure. It has no message other than that it's possible to get lost in the jungly wetness of Venus and yet survive - provided you can get to one of the refuges provided by the authorities.

The refuges are called Sun Domes. In this story the survivors of a rocket-crash are trying to reach a Sun Dome. If they can do that, they'll live. Otherwise, exposure to the everlasting downpour, the eternal rain on Venus, will drive them insane and kill them. It's as simple as that.

The lieutenant turned and looked back at the three men using their oars and gritting their teeth. They were as white as mushrooms, as white as he was. Venus bleached everything away in a few months. Even the jungle was an immense cartoon nightmare, for how could the jungle be green with no sun, with always rain falling and always dusk? The white, white jungle with the pale cheese-colored leaves, and the earth carved of wet Camembert, and the tree boles like immense toadstools - everything black and white...

Bradbury makes the reader feel that he, too, is walking in the Venusian rain,

in the rain that fell heavily and lightly, heavily and lightly; in the rain that poured and hammered and did not stop...

Eventually, after a disappointment when they find a wrecked Sun Dome, one of the men cracks.

"Stop it, stop it!" Pickard screamed. He fired off his gun six times at the night sky. In the flashes of powdery illumination they could see armies of raindrops, suspended as in a vast motionless amber, for an instant, hesitating as if shocked by the explosion, fifteen billion droplets, fifteen billion tears, fifteen billion ornaments, jewels standing out against a white velvet viewing board. And then, with the light gone, the drops which had waited to have their pictures taken, which had suspended their downward rush, fell upon them, stinging, in an insect cloud of coldness and pain.

It carries you along, doesn't it, that style?

Stid: It's supposed to, Zendexor. That's good writing for you.

Zendexor: Yes, it is, but if it weren't for one thing, I'd be feeling too much hammered, by the message, message, message, the message that space travel is too much for Man, that if you go out there you'll find things that human beings weren't meant to endure...

Harlei: Go on then, tell us that one thing which saves the story for you.

Zendexor: Simply the fact that one of the men survives! The one who keeps his head, who doesn't give way to despair - well, I won't tell you what happens exactly. It's a relief, I will tell you that much. You then sit back and think, wow what a tale.

Ray Bradbury, "Dwellers in Silence" (Planet Stories, Spring 1949); "The Exiles" (as "The Mad Wizards of Mars", McClean's, 15 September 1949; revised and reprinted 1950 in Fantasy and Science Fiction); "The Golden Apples of the Sun" (in the collection of that name, 1953); "The Fire Balloons" and "The Long Rain" in The Illustrated Man (1951); The Martian Chronicles (1950); "Perchance to Dream" in The Day it Rained Forever (1959); Dorothy L Sayers, The Mind of the Maker (1941)

See A Return to Bradbury's Mars, for The Ugly Duckling by Matthew Hughes.

For an excerpt from The Lost City of Mars, see Mars Quiz.

For the distant connection between science and beauty in Ylla, see the OSS Diary, 3rd February 2017.

For comparison of The Long Rain with Poul Anderson's The Big Rain, see the Diary entry for 4th August 2018.

One step up from Bradbury's Martian resistance discusses Wallace West's Dawningsburgh.

For Rocket Skin see Hitch-hiking from world to world.

See the Diary entry on Brackett, Bradbury and "past-future" dates.

See the History of Hopes for the year 1971, for Bradbury's comment during the 12 November symposium at Caltech, as Mariner 4 approached Mars orbit.

Extracts - An asteroid haunted by disembodied minds - Illusion-Trap on Mars - Electrical storm on Venus - Involuntary adaptation on Mars - Terran on Mars possessed by a native mind - Existing on Mars, neither alive nor dead.

>> Authors