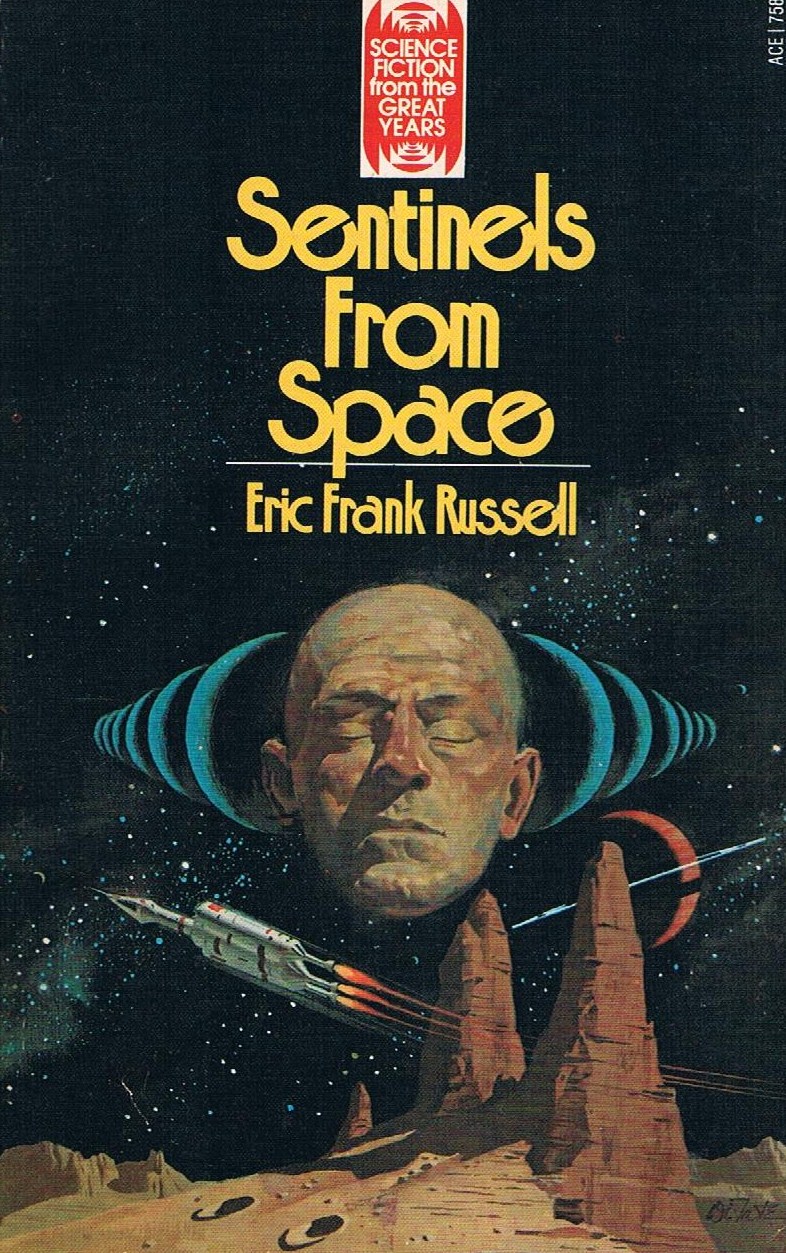

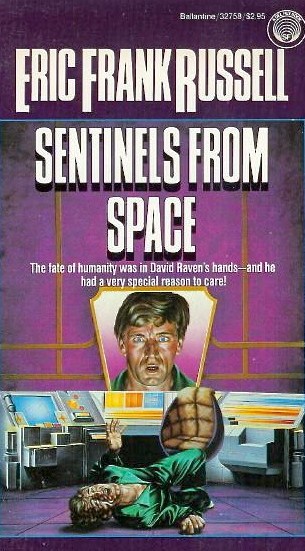

sentinels from space

by eric frank russell

A strangely neglected treasure - 244 pages of irresistible golden age story-telling, aglow with the charm of the master.

Stid: Then why has it been neglected?

Zendexor: Galumphing galaxies! - don't ask me; I haven't a clue. It can't be any lack of appreciation for Russell as a writer, because even his highly appreciative biographer, John L Ingham, hardly mentions the work in his Into Your Tent: the Life, Work and Family Background of Eric Frank Russell. A baffling omission.

Stid: Well then, go on and start enthusing about the book - I take it your intention is to make up for its lack of the fame it deserves.

Zendexor: That is indeed my intention, but the task makes me nervous. I don't want to make a mistake and give the wrong impression... Russell's literary virtues seem obvious at first. His style contains absolutely no flab; he is clear, witty, pointed or wise-cracking in a half tender fashion, full of humanity. But having said all that - which might in some respects apply also to Keith Laumer's work - Russell has a hard-to-pin-down panoramic aspect to his tales, a kind of golden spaciousness that is his equivalent to Laumer's more focused, mythic intensity.

Stid: Sounds to me like you're floundering, Zendexor. All this isn't going to give the interested reader much clue as to what Sentinels of Space is about.

Zendexor: Who cares? The importance of plot is vastly over-rated - at this stage, at any rate. The background, the settings and the style are what a fan needs to know when choosing whether to spend some hard-earned quality time with a book.

It would be more revealing simply to describe my emotions when I first saw the book on a shelf in a shop - it was a specialist sf bookshop in Oxford, I think, back in 1978 (the year Russell died). I saw this book and my eyes popped out, cartoon-fashion. A whole novel by EFR, one which I'd never heard of!!! Rarely do moments like that occur in one's life. Compared to that emotional evidence, plot-details seem small beer.

Harlei: I agree with Zendexor: I want to know what sort of book it is; as for its events, I'll encounter those when I read it, if I decide to. And so far, Zendexor's remarks make me want to. But now, Z., it's time you coughed up about the background.

Zendexor: Terran Security employs mysterious agent David Raven to combat sabotage by colonists from Mars and Venus who want political independence. Earth has heard rumours of interstellar visitors and wants humanity to hang together, united in the face of possible peril, but the colonists, who include a disproportionate number of powerful mutants due to the genetic effects of space-travel, despise old Earth and want to go their own way.

The story begins:

The World Council sat solemn and grave as he walked toward them. They numbered twelve, all sharp-eyed, gray or white of hair, their faces lined with many years and much experience. Silently with thin lips, firmed mouths, they studied his oncoming. The thick carpet kept saying hush-hush as his feet swept through it. The expectant quietness, the intent gaze, the whispering of the carpet and the leaden weight of deep, unvoiced anxieties showed that this was a moment distinct from other minutes that are not moments.

Reaching the great horseshoe table at which the council members were seated, he halted, looked them over, starting with the untidy man on the extreme left and going slowly, deliberately around to the plump one on the far right. It was a peculiarly penetrating examination that enhanced their uneasiness. One or two fidgeted like men who feel some of their own sureness beginning to evaporate. Each showed relief when the soul-seeking stare passed on to his neighbor.

In the end his attention went back to the leonine-maned Oswald Heraty, who presided at the table's center. As he looked at Heraty the pupils of his eyes shone and the irises were flecked with silver and he spoke in slow, measured tones.

He said, "Captain David Raven at your service, sir."

Leaning back in his chair, Heraty sighed, fixed attention upon the immense crystal chandelier dangling from the ceiling. It was difficult to tell whether he was marshaling his thoughts, or carefully avoiding the other's gaze, or finding it necessary to do the latter in order to achieve the former.

Other members of the council now had their heads turned toward Heraty, partly to give full attention to what he was about to say, partly because to look at Heraty was a handy pretext not to look at Raven. They had all watched the newcomer's entrance but none wanted to examine him close up, none wanted to be examined by him.

Raven and Leina

Raven and LeinaHarlei: I bet Raven's a telepath. That's why they're so nervous.

Zendexor: Yes, it's a case of set a mutant to catch a mutant. Earth has "skewboys" of her own, a far smaller percentage than that possessed by the colonies, but nevertheless a sizeable total in view of Earth's vastly greater population. Raven is the one picked by Terran Intelligence. But we keep getting hints that there's something extra odd about him, paranormal in a sense which doesn't apply to the known types of mutant.

However, these mysterious hints - resolved into a conceptual breakthrough at the end of the book - don't interfere with the main narrative.

Stid: And you're glad of that, are you? You're saying, that most of it is an ordinary tale of intrigue and derring-do, with a big mystery tacked on the end that's maybe not really necessary?

Zendexor: You're twisting my words a bit. Let me put it this way: I think the mystery turns out in the end to have been a useful framing context for the whole story, but the charm of the book lies in that main straightforward story of a Terran agent investigating and thwarting anti-Terran plotters.

And what plotters! They're a memorable bunch, especially the two Venusians, Thorstern and Kayder.

Russell is good at portraying the personality clashes and the battles of wits between Raven and the non-mutant megalomaniac Thorstern, who compensates in ingenious ways to compensate for the fact that he is a "pawn", a non-mutant, with no special powers except his keen intelligence and ruthless ambition.

Equally well-handled are Raven's encounters with Kayder, an "insectivocal" mutant - one who can command insects.

A squat, broad-shouldered man with heavily underslung jaw, Kayder was of Venusian birth and probably the only Type Eleven Mutant located on Earth. He could converse in low, almost unhearable chirrups with nine species of Venusian bugs, seven of them highly poisonous and willing to perform deadly services for friends. Kayder, therefore, enjoyed all the appalling power of one with a nerveless, inhuman army too vast in numbers to destroy.

The irascible, dangerous Kayder starts as a tool of Thorstern, but eventually, in a memorable dialogue, is persuaded by Raven to change his stance - one of the best scenes in the book.

The showdown with Thorstern happens on Venus. It's a good old fertile forested Venus, somehow introduced without any strain.

...Between enormous top branches as thick as the trunks of adult Earth-trees he went down like a drifting leaf, hit ground with enough force to leave heel marks in the coarse turf.

This point was little more than a mile from the rim of the great plain. The gigantic trees were thinned out here, growing widely apart with quiet, cathedral-like glades between them. Fifty or sixty miles westward the real Venusian jungle began, and with it the multitudinous bad-dream forms of ferocity that only lately had learned to keep their distance from the even deadlier form called Man...

Thorstern is a formidable foe, a schemer who multiplies himself with look-alikes (using those face-changing mutants called malleables). His Venusian headquarters provides a setting worthy of a show-down.

in the castle

in the castleA great black basalt castle was the home of Emmanuel Thorstern. It dated back to the earliest days of settlement when smooth, high walls six feet thick were sure protection against antagonistic jungle beasts of considerable tonnage...

Seven other similar castles elsewhere on the planet had served the same function for a time, then had been abandoned when their need had passed. These others now stood empty and crumbling like dark monuments to this world's darkest days.

But Thorstern had stepped in and restored this one, strengthening its neglected walls, adding battlemented towers and turrets, spending lavishly as though his calculated obscurity in matters of power had to be counter-balanced by blatancy in another direction. The result was a sable and sinister architectural monstrosity that loomed through the thickening fog like the haunt of some feudal maniac who held a countryside in thrall. (For more on this castle, see the page on characters of worlds.)

Stid: Neat, the way Russell disarms criticism. The sinister castle is a cliché, but the author, while profiting from its image-value, simultaneously shows us that it is Thorstern's cliché, not Eric Frank Russell's. So he doesn't have to pay any price for it in lost freshness or credibility.

Harlei: And it sounds to me as though it's fairly done. It's EFR's way of showing us what Thorstern is like. The castle is an expression of his personality.

Zendexor: And later dialogue brings it out, superbly. Here is an example -

"You wish to talk about murder?" Raven asked. "That's a subject you're qualified to discuss."

That was an obtuse crack at himself, Thorstern felt. An undeserved one. Whatever else he might be, he was not a bloodthirsty monster. True, he was running what whining Terrans saw fit to call an undeclared war but in reality was a liberation movement. True also that a few lives had been taken despite instructions that blows be struck to exact minimum loss of life and maximum loss of economic power.

A few killings had been inevitable. He had approved only those absolutely necessary to forward his designs. Not one more, not one of any sort. And even those he had dutifully deplored. He was by far the most humane conqueror in history, bidding fair to achieve the biggest and most spectacular results at the least cost to all concerned.

"Would you care to explain that remark? If you are accusing me of wholesale slaughter I'd like you to state one instance, one specific instance."

"There are only individual cases in the past. The greater atrocities are located in the future, if you consider them essential... you know how true that is, how far you are prepared to go, how great a cost you are willing to pay to boss a world of your own... it is written in the depths of your mind. It stands out in letters of fire: no price is too high."

Thorstern could find nothing to say. There wasn't an effective answer. He knew what he wanted. He wanted it cheaply, with as little trouble as possible. But if tough opposition should jack the price sky-high in terms of cash or lives it would still be paid, with regrets, but paid.

Raven uses psychology and brains as well as his special mutant powers to defeat his opponents. Dramatic personality clashes are a feature of the story. But the Venusian forest, the black castle, and Kayder's Terran hideout are "characters" too. For any OSS fan who hasn't read Sentinels of Space, this is a treat in store.

John L Ingham, Into Your Tent: the Life, Work and Family Background of Eric Frank Russell (2010); Eric Frank Russell, Sentinels From Space (1952)

See the extract, Manhunt on Venus.