the intrepid travelogue:

slaves of venus

An investigation by

Dylan Jeninga

The menace of slavery is unfortunately common throughout the system, and it may be found anywhere from the scorched rocks of Mercury (Slaves of Mercury, Nat Schachner) to the ochre plains of Mars (A Princess of Mars, Edgar Rice Burroughs) to the green hills of Earth (real life). While it is undoubtedly a great injustice no matter the planet, I have recently had the opportunity to read two fine stories of subjection beneath the overcast skies of Venus, one from the NOSS collection Old Venus and one from the golden age of OSS fiction.

The first is Pale Blue Memories by Tobias S. Buckell. It takes place in a timeline where World War Two never ended, but stretched into the space race, with Nazi moon bases and a race to be the first to reach a planet. The Allies seem poised to claim that prize, but enemy machinations bring the Allied rocket crashing to the surface of Venus, taking our hero, called only “Charles”, with it.

Charles’ mother is caucasian and his father’s skin is light in tone, but in 1950’s America his African ancestry makes him keenly aware of a divide between him and his crewmates. He knows he would not be accepted by them if they knew where his father’s family came from.

People from my kind of family didn’t end up becoming astronauts. My kind of family had aunts and uncles who had to drink from the other fountains and couldn’t order stuff from the front.

My dad came from Jamaica, towing behind the rest of his family. They came looking for jobs and ended up working out in the Illinois countryside. White folk could tell Dad wasn’t white, but they weren’t sure what exactly he was, due to his kinky hair and skin that browned when he worked outside too long.

His heritage, though concealed, drives him to join the air force when he hears about a blacks-only fighter squadron devastating Hitler’s Luftwaffe. As he says,

The Red Tails were breaking records in their section of the sky. I was secretly doing it over here. And one day I’d reveal myself. And it would be known that I was as good as any other pilot.

When his rocket comes down on the surface of Venus, Charles fears that the world will never know what he has accomplished “despite” his ancestry. But the landing is not as fatal as he fears. Most of the crew survives, and Commander James Heston orders Charles and another crewman named Eric out into the jungle in search of clean water while the rest of the crew inspects the damage to the rocket.

The jungles of Venus are strange and alien, with purple vegetation and giant insects, but when the two finally encounter Venusians they find them disconcertingly familiar: mounted, armed with guns, and apparently aggressive. They and the rest of the crew are captured and brought to a nearby fortress, where their captors trade them for guns. Despite their predicament, the commander holds out hope.

“They don’t know we came from the sky,” Eric said, his voice quavering slightly.

“Then we learn the local lingo,” Commander James said quietly. “However long it takes us. And we tell them. They can see, with their own eyes, that we look different.”

“For all they know,” I said, speaking for the first time that morning, “we’re strange Venusians from some unknown location on their planet.”

“Stow that talk,” Heston ordered.

Even through a grueling walk and a dehumanizing auction, Heston remains convinced that if he can just make himself understood, he will win the crew their freedom. However, when a translation-slug inserted through his nostril gives him his chance, things don’t go as he hoped.

Heston held onto my shoulder. He was excited. “We’re visitors! We’re from another world.” He pointed up at the dark, grey clouds that stretched from horizon to horizon. “We’re from beyond the clouds.”

The Venusians around us laughed. A yipping, barking sound. “There is nowhere else but the surface, and there is nothing beyond the clouds but more clouds and emptiness.”

Heston wouldn’t let it go. He kept arguing. And eventually his shouts led to warnings, then the Venusians clubbed him until he shut up. They forced me to carry him, dazed, across the courtyard into a small, cramped common house.

Still, the Commander doesn’t give up.

“If we can just talk to the right people,” Heston whispered, as we walked back. “We need to find a politician or a scientist. We need to talk to their leaders, not workers and overseers. Talk to just the right person in power, it will be okay.”

The commander believed that. He believed that because for him it had always been true. His life had ups and downs, but for true injustices, he’d always been able to find the right person to set things right.

Heston’s naive optimism highlights an often purposeful misunderstanding of the system of slavery on the part of the oppressors. The idea that it isn’t so bad, that it’s just in some way, or that it only happens to certain sorts of people and that it could never happen to the ones who do the enslaving. For the captain, this delusion springs from the American need to avoid guilt over the African slave trade.

I tended to a dazed Heston after his beating, trying to get him to drink water. I was trying to get him oriented because he was floundering. “You know free economies are rare, Commander. Even on Earth. It’s not surprising, really. If aliens were to land on Earth and look vaguely like us, it might not have been good for them either, being different. Imagine if aliens had landed in the South, before the Civil War that we had to fight so bloodily to get rid of this stain…”

Through bruised lips and swollen eyes, Commander James said, firmly, “The War of Northern Aggression was fought over states’ rights.”

And with a grunt of pain, he picked up his blanket, his dog tags that he’d been allowed to keep, and dragged himself over to the other side of the common house.

Pale Blue Memories goes on to depict the psychological and physical toll enslavement takes on its victims, especially the pervading sense of hopelessness it creates. It’s a deeply moving story, and one I recommend to any fan of science fiction, OSS or otherwise, as part of an education for being a “citizen of the world”, so to speak.

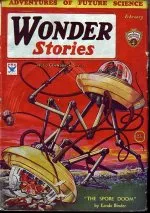

The second story is Logic of Empire, by Robert A. Heinlein. It’s about a modernized incarnation of slavery, without the chains but just as inescapable. It begins with our hero, Humphrey Wingate, doubting the claim that the “labor clients” who work for The Company on Venus may be called slaves at all.

“Don’t be a sentimental fool, Sam!”

“Sentimental, or not.,” Jones persisted, “I know human slavery when I see it. That’s what you’ve got on Venus.”

Humphrey Wingate snorted. “That’s utterly ridiculous. The company’s labor clients are employees, working under legal contracts, freely entered into.”

Jone’s eyebrows raised slightly. “So? What kind of contract is it that throws a man into jail if he quits his job?”

“That’s not the case. Any client can quit his job on the usual two weeks notice - I ought to know, I -”

“Yes, I know,” agreed Jones in a tired voice. “You’re a lawyer. You know all about contracts. But the trouble with you, you dunderheaded fool, is that all you understand is legal phrases. Free contract - nuts! What I’m talking about is facts, not legalisms. I don’t care what the contract says - those people are slaves!”

One wild evening of drinking and a poorly thought-out bet later, and we see both characters signed on as clients for The Company and aboard a rocket about to stop at Luna before heading on to Venus. The sobriety of morning makes it clear that they have made a mistake, but backing out is not so easy.

The Chief Master at Arms listened to Wingate’s story with obvious impatience, and interrupted him in the middle of it to consult his roster of emigrants. He thumbed through it to the W’s, and pointed to a line. Wingate read it with a sinking feeling. There was his own name, correctly spelled.

“Now, get out” ordered the official, “and quit wasting my time.”

Not wanting to give up, Wingate tries again, this time with the ship’s Purser.

“The whole thing is ridiculous”, he protested. “I insist that I be taken to see the Captain - I can break that contract in ten minutes time.”

The Purser waited before replying. “Are you through speaking your piece?”

“Yes.”

“Very well. You’ve had your say, now I’ll have mine. You listen to me, Mister Space-lawyer. That contract was drawn up by some of the shrewdest legal minds in two planets. They had specifically in mind that worthless bums would sign it, drink up their bounty money, and then decide they didn’t want to go to work after all. That contract has been subjected to every sort of attack possible and revised so that it can’t be broken by the devil himself.

You’re not peddling your curbstone law to another stumble-bum in this case; you’re talking to a man who knows just where he stands, legally. As for seeing the Captain - if you think the commanding officer of a major vessel has nothing more to do than listen to the rhira-dreams of a self-appointed word artist, you’ve got another think coming! Return to your quarters!”

Nevertheless, Wingate clings to the hope that there must be some avenue of escape. He persists in searching for a legal loophole;

“We were signed up less than twelve hours before ship lifting. That’s contrary to the Space Precautionary Act.”

“Yes - yes, I see what you mean. The Moon’s in her last quarter; they would lift ship sometime after midnight to take advantage of the favorable earthswing. I wonder what time it was when we signed on?”

Wingate took out his contract copy. The notary’s stamp showed a time of eleven thirty-two. “Great Day!” He shouted. “I knew there would be a flaw in it somewhere. This contract is invalid on its face. The ship’s log will prove it.”

Jones studied it. “Look again.” he said. Wingate did so. The stamp showed eleven thirty-two, but A.M., not P.M.

“But that’s impossible.” he protested.

“Of course it is. But it’s official. I think we will find that the story is that we were signed on in the morning, paid our bounty money, and had one last glorious luau before we were carried aboard. I seem to recollect some trouble getting the recruiter to sign us up. Maybe we convinced him by kicking in the bounty money.”

“But we didn’t sign up in the morning. It’s not true and I can prove it.”

“Sure, you can prove it - but how can you prove it without going back to Earth first!”

And when that fails, he resorts to desperate flight once they reach the Moon. But Jones quickly puts an end to that plan.

“Have you ever tried running in total vacuum?”

The next few months are an eye-opening experience for Wingate, as he learns to his great unhappiness that just because something is technically true does not mean it is true in practice. It’s an excellent exploration of how an antiquated institution like slavery may survive into the modern day through contracts, conveniently unspoken facts, and conditions which conspire to ensnare the victim as completely as any cage.

A common thread between the two stories, apart from their setting on the second planet, is the theme of willful ignorance on the part of those who don’t see themselves as enslave-able. Just as Commander Heston could not accept the hopelessness faced by the victims, so too did Wingate refuse to believe that there was even slavery in the first place. It’s a bitter pill to swallow, and most won’t do it: even when Wingate has a hard-earned change of heart and tries to spread the message to others, he discovers that few are likely to listen. Both stories end with forlorn acceptance that an institution like slavery is not going to be escaped or eliminated in a day. As Jones says to Wingate,

“But - Oh, the devil! What can we do about it?”

“Nothing. Things are bound to get a whole lot worse before they can get any better. Let’s have a drink.”

Not a very hopeful message. For my next Travelogue, I shall endeavor to find something more light-hearted to write about, to balance the mood.