kroth: the drop

1: the sagging sky

Morning sunshine nudged my eyelids open. Or more likely I was woken by the jangle of harness, the clink of weapons or maybe a voice – for the head on the other sleeping bag tilted up, same as mine, as with one accord we turned to stare southwards.

“Jumping holy smoke,” breathed Uncle Vic, raising himself on one elbow.

No more need to wonder whether daylight would bring us a glimpse of the enemy...

Vic uttered some more curses; I could not get a word out. Glimpse the enemy? They were bivouacked in every direction. Not only down-Slope but up-Slope, and to East and West, they surrounded us.

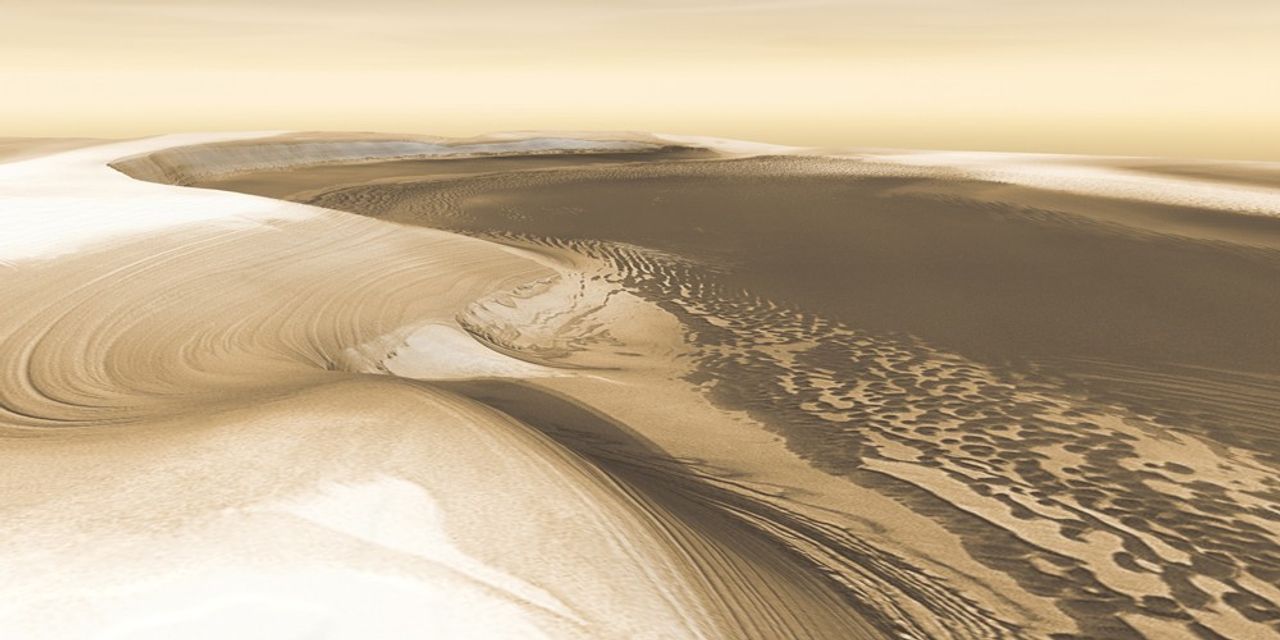

Last night our impression was that we had camped in a glade. Now the entire prospect was opened up by the daylight, the terrain exposed as it really was, the trees far fewer than when they had loomed in darkness. This allowed the thirty-degree world-tilt of Latitude Sixty to sweep downward panoramically before our eyes. We saw, not a forest holed with glades, but a bush-speckled grassland tipped towards the southern blue. And dotted around us on the incline were tens of thousands of dismounted Gonomong.

They were not just an army but an entire population, many of them awake, stretching, yawning, peering about like ourselves. Each group, or individual, was camped beside its steed, a giant “inchworm” decapod similar to ours, and since the backs of these creatures arched nine feet or so up from the ground, all the way into the far distance the Slope was pimpled with such knolls.

It was hard not to stare in too obvious amazement, while our minds raced to figure out how we could have gotten into this.

Our foes had evidently spent the night around us in widely scattered formation. A group might consist merely of a man and his steed, or more typically it might also include a woman and two children, more rarely an extended family with two or three steeds between them, but each group had camped twenty or thirty yards from its fellows, doubtless so as to ensure a wide enough patch of grass for the animals to eat.

Had it not been for this spacious arrangement, of course we would never have slipped in amongst them during the night... but be that as it may, no matter how it had happened, we had got ourselves thoroughly inside the horde.

“Well,” muttered Vic at last, “one important decision has been made for us, anyhow.”

“Yeah,” I said. “How to approach.”

“And mingle. Well, we’ve got away with it.”

“So far,” I cautioned. “But we’d better not go wandering round the encampment.”

Vic eyed me.

“A very good point, Duncan. I was about to say the same to you. No wandering about on foot, even on a hunch as to where Elaine is being held. No romantic heroics.”

“Do you seriously think –” my voice sank to a low growl: “Oh, leave it. I know what you’re getting at.”

Heaving himself upright Vic remarked, “The press don’t get everything wrong.”

“Just leave it, Uncle, please. No teasing about those newspaper reports; no jokes, no digs, about that hero stuff.”

He didn’t make any such promise. All he said was, “Come on, let’s get ready.”

It was indeed a good idea to look busy. More of the enemy were awakening, while the bright and early ones began to rummage in the saddlebags of their mounts. Nobody took any notice of us as they proceeded to munch their breakfasts and prepare for the new day’s march, but if Vic and I had stopped to have an argument, might one of them have looked in our direction? Wondered at our delay? Come closer and pierced our disguise? It was a risk we dared not take.

So we kept a lid on our dispute as we pottered about, breaking out some rations and adjusting our gear, and while we were at these little tasks we watched our adversaries without being too obvious about it, all the time hoping and praying that our disguise was sufficient. If it was not, then we were caught already.

I was, however, determined to make my point.

At a chosen moment, in a low voice, I began: “Uncle, listen, I don’t want to argue, but, you and I both know what the General was up to.”

“Yes?” said Vic, infuriatingly quizzical.

“The General,” I ploughed on, “built me up into a hero for political reasons. He needed to get round any public phobia about my ‘taming’ of the decapod.”

“Isn’t that fair enough?”

“Yes it’s fair enough but it’s a dangerous game for me, d’you see? Dangerous to land me with a lot of other people’s expectations which I won’t be able to fulfil. So no more playing up to it, eh?”

Vic heard me out with a tolerant smile on his face. “Very well – I obey.”

Within a few more minutes we were both ready to ride. Thenceforth we just had to kill time until we could depart roughly in synch with the others around us.

I toyed with the idea which Vic had put into my head. What would I do if I were a hero? The temptation, in that case, would be to go for an investigative stroll, an innocent little wander, during these minutes before the Gonomong host set out on the next stage of their migration. A number of individuals were, after all, ambling about. It could be done. Something might be learned.

But then, I reflected, heroes are often stupid. They have to be, to get into scrapes, which they can then use their heroism to get out of...

“What’s funny?” murmured my watchful companion.

“James Bond,” I said, “always gets captured – the chump.”

“Whereas we,” Uncle replied, “can trust each other to be realistic.”

Indeed, we were both very careful to keep close to our mounts. We never for one moment forgot Professor Brudenell’s theory, which held that our association with those creatures was our only disguise. That was why we must refrain from snooping around on foot. We had absolutely no choice but to trust the theory.

Yet when I looked around at the thousands of Gonomong within sight of us, so differently clad and so differently muscled from ourselves, I could not help but think, we stand out much too plainly. Even our weapons were different from theirs: we were armed with pistols, whereas they carried heavy swords plus those hooked poles with which they’d lunged so effectively during the recent battle. We could have picked up some for ourselves, from the many lying on the battlefield, but what would have been the use? We weren’t trained to wield them, we didn’t have the exaggerated Gonomong physique, and to handle enemy gear incompetently would have been as much of a give-away as to lack it. Yes, we stood out a mile; we had no choice but to hope that Brudenell had been right, that their mentality could not conceive of anyone but one of themselves riding and controlling a decapod. Amazingly, then, so long as they pictured us as riders, they just wouldn’t notice the unfamiliar style of our clothes, or that our arms were thinner than our legs, or that our weapons differed from theirs...

“Ha... this looks like it.”

Vic had sensed the change before I did. Nobody had given any trumpet call; the word must have gone around in some quiet fashion. “When we march,” Vic advised, “I’d say: keep an absolute minimum five-yard separation from the closest.”

“I certainly agree with that.”

For though our foes’ beliefs limited what they could see, this obliging cloak of invisibility would not cover us if we got too close. It wouldn’t work within touching range.

Now all the riders within our sight range were mounting their crouching “inchworms” and ordering them to stand. We did the same: Vic onto Gnarre, and I onto Ydrad.

As soon as I had scrambled onto that part of the neck that was moulded into saddle-shape, my emotions likewise “moulded”, became tailored to fit the notion that I was seated upon some more ordinary steed’s back, instead of on a monster’s neck. I might have been horse-riding, an impressionistic lie which forms part of the “settling in” service that these strange creatures can perform for us, the reason why, bizarre though they look, they can be so useful to man. My mind gave the order and Ydrad rose on eight stubby legs, while the extra two front limbs clutched redundantly at the empty air like the odd little arms of a tyrannosaur. To either side of me I saw multitudes of other beasts start to move forward, down-slope, and I sent a commanding thought at Ydrad to do the same.

Up, forward, down, plonk, up, forward, down, plonk... I would have gone crazy in no time, had not the “settling” adjustment also applied to the thing’s motion, translating the weird inchworm gait into the feel of an equine trot, as we plonked southwards. All part of the service.

Not that I could quite forget the peculiarity of what I was doing. My view of the scene immediately in front was less good than it would have been if I had been riding a horse. The “nib” or backward crest on the decapod’s head, a good shield in battle, was bound to restrict the rider’s front view; I therefore had to lean sideways and peer round the great neck if I wanted a better look forward. Admittedly, eye-holes had been drilled through the crest’s bony substance, but I, less expert than the Gonomong, found it hard to sprawl in best position as Ydrad humped and stretched forward and down, forward and down, forward and down on the interminable thirty-degree Slope.

That mind-boggling Slope! Words are pitifully inadequate to convey, not only the fantastic strangeness but the equally astounding familiarity, of our journey. Any journey, no matter how extraordinary, must develop its own routine, whereby you adjust to the laws of the situation and accept them. Just as a steeplejack needs a head for heights, so an explorer south of Kroth’s Latitude Sixty needs that inner adjustment known as The Slant. It works in so many various ways, that hardly a day went by without a new – er – slant on the matter. That first day, for example, The Slant shifted the blame for being unreal back onto poor old Earth. How could I have taken Earth seriously? How could “up” mean one thing in one place, another in another? How could land lie horizontal all over a globe? A string of thoughts insisted that the Slope which I was on now was the only reasonable reality. Earth, not Kroth, must be the fanciful story. Earth with its crazy vari-directional gravity, its Southern Hemisphere where people didn’t know that they walked with their heads down – what a laugh!

Yet the laugh wasn’t too strident. The Slant never over-stated its case. Its arguments were soothing background mental melodies. The result was, my intelligence was lulled, but not my fundamental awareness of what was true. The Slant was wise in its practical purpose. It gave me just enough stability to keep me from being ambushed by terror. It offered me a profitable deal, by which I could dispense with the fear, but retain the wonder, of that awesome journey.

A sly trend in my motivation, whereby for longer and longer stretches I simply forgot that my purpose was espionage, made the descent southwards seem like an end in itself. “Call me an explorer, not a spy. What sights I may see, clambering around this great world. So long as I don’t fall off it, that is – and if I am able to flick aside that nightmare thought, I must really be fit… in the light of the discovery that I am free from fear… fit and level-headed enough to ask, is it not in the realm of the possible, is it not a feasible as well as a wonderful idea, that I go for what must be the best, the most spirited career of all, the profession of explorer? Here am I, being offered that wonderful option of what to do with my life! What a complete jam-filled dodger am I!”

If only it hadn’t been for one nuisance:

The enemy, you twit. Try not to forget the enemy.

Out, out of my daydream I swam –

Swam up into an “oops” moment, that booted me fully awake.

We were not hired as explorers, we were spies. Trapped spies, most likely. Surrounded by an army of riders who were sure to enslave us the moment they learned who we were.

In view of this, how the heck were we – my only surviving relative and I – ever going to get back with the information we had been sent to obtain, even if we succeeded in obtaining it?

*

At the end of the first day’s march we camped a quarter mile or so to the east of a pale, dusty track in the grass, which I had learned to identify as the Wayline.

On average it was about five yards wide. It ran straight north-south; it was, in fact, the world’s line of zero longitude.

Interesting, that it was still maintained down here, still kept visible as a path so far south... such a long way down from the boundary of Upland civilization. Vic and I had crossed the ancient track a few times as we threaded our weaving course, hour after hour through the moving host, in a vain effort to locate the prisoners.

“We’re not getting anywhere,” I complained. Now that we had hunkered down to brood about the situation, the hopelessness of our task seemed overwhelming.

“Better turn back?” Vic suggested.

“Assuming we can,” I mused in wonder at the turns which life can take. Then, making a big effort to focus upon my duties, I said: “We’ll try it, of course.”

“But how?”

“Straggle back, pretend we’re foraging, choose the right moment and hope nobody notices... But first, before we abandon our mission, we’ve got to be sure we’ve failed.”

Vic was a good prompter. He said patiently, “What do you aim to do?”

“Phone home for instructions.” I gazed at the little screen of the phone in my hand. It had an indicator for signal strength, a rectangle of green light which had nearly, but not quite, gone dark. “We’re close to the limit of this thing. Another day like this and I reckon we’ll be out of range.”

“Ah,” said Vic, non-committal, and lent a close ear while I dialled the number I had been given by General Faraliew. I hoped that none of the Gonomong, looking in our direction, saw anything other than two figures, one of them (me) with his fist by his head, chatting as they crouched by the flank of a decapod.

The ring tone was replaced by a crackly voice: “Hello?”

It wasn’t the General.

“Duncan Wemyss here. Is that the Professor?”

“Brudenell here. Thank goodness you’re back in touch.”

“We’ll soon be out of range,” I continued, “so I thought I’d better report, though I can’t yet report any success – we haven’t found the captives.”

“What do you mean, you’ll soon be out of range? Don’t let it come near that!”

“You want us to turn back?”

“Of course we want you to turn back!”

“Even at the cost of abandoning our people?”

“Just a moment.”

I heard a cross-connection being established, some faint conversation almost drowned in a hiss, and then a new voice spoke to me.

“Wemyss, this is Colonel Reece. I applaud your determination. But the captives are beyond our help now, even if you did locate them. Our only chance was to make a fairly quick snatch, and obviously that’s not on. It’s far too late for a rescue raid – the distances involved preclude the possibility of surprise. I’m sorry, Wemyss. You’ve done a splendid job in testing our capability for –”

“Just hang on, Colonel,” I interrupted; “give me a few seconds, please.” I closed my fist around the phone and, with a shift of stance, glanced around; then I resumed: “Sorry about that, sir; I just felt the need to check that no one appears unduly curious about what I’m doing. It all goes to show – I mean, to extricate ourselves from this lot we’ll need to wait for exactly the right moment...”

“Get out as soon as you can without risking your cover,” Reece snapped, sounding really worried. “Wait till dark – and don’t add to our glut of dead heroes; Topland needs you back in working order! Now stand by while I pass you back to the Professor.”

More faint squeaks against a hiss and crackle; and then Brudenell’s voice came through.

“The colonel’s off the line now, Wemyss. Listen to me and give me an honest response. I have made quite a study of previous forays down into Slantland. I wonder if you realize how few of the explorers ever came back.”

“Now you tell me,” I said wryly.

“I said explorers, not mere scouts.” He enunciated his words with a care which made him seem even more anxious than Reece. “And from the reports of those who did return, I’ve deduced that the ‘hungry horizon’ is the most –”

“Sorry about this, Professor. I’m going to have to cut you off there.” Click. I put the phone in my pocket and then my eyes met those of Vic.

He said, “Ah. I see. Phone home for instructions, then ignore them.”

“They were just trying to scare us off,” I countered, but then remorse smote me and I was appalled to discover my intention: I am determined to persist. I am never going to give up. So that was my attitude – but what right had I to risk not only my own life but my uncle’s in a mission which I intended to prolong in defiance of orders? “Sorry, sorry,” I spoke through my fingers, my head in my hands. “I ought at least to have let Brudenell finish what he was saying.”

I felt a hand on my shoulder. “Don’t assume,” said Vic, “that you’re the only pig-headed mutinous person around, because you’re not.”

I looked blearily askance.

“Eh? Are you with me on this?”

“I certainly am,” he said gently, squatting beside me. “The ‘hungry horizon’ has opened its jaws for me too.”

“I don’t like that kind of talk, Uncle.”

“Which is why you cut Brudenell off.” He stared South, his lips set in a grim line. “The fact remains: I’m not for turning back, any more than you are.”

He had neither the need nor the wish to say any more, and I likewise took refuge in silence, as evening advanced and darkness fell. This was the hour, according to the colonel’s command, that I should plan our exit from the scene. I made no effort to do so; I was, indeed, mutinous. And perhaps this wasn’t all, perhaps I was also stupid. To interrupt Brudenell before he had finished his warning – how daft was that?

*

The opportunity still existed to phone again, to apologize, give some excuse as to why I had not listened properly, and then say, please, Professor, I do want to hear what you were going to tell me about the “hungry horizon”, the sag-jawed sky.

The opportunity lasted till the beginning of next day’s march. I let it slip by. We had been on the move for half an hour when I tried the phone again, and the signal was gone for good.

*

Late that afternoon, I voiced a suggestion:

“One thing we haven’t done yet, is scout around near the front of the line of march.”

Vic understood. “You think the captives may be under escort ahead of the main body.”

“Yes – if they’ve been given special priority,” I amplified. “It’s all ‘maybe’, but after all, if they’re valuable, if they’re important booty, the Gonomong may have decided to hurry them on. It would be easy to go faster than this.”

For we were in the midst of a whole people on the move, a horde which marched at the pace of the slowest.

“And what if we spot them?”

“Then – our options are still open.”

(Yes, we could still decide to be good boys, to obey orders, to remember that we were scouts only, not rescuers.)

For the rest of that day, and the first half of the next, we wormed our way towards the front of the horde. It was easier to do this than it would have been in a properly organized army. I say this, though of course the great migration may well have been highly organized in some way that was undetectable to a stranger; be that as it may, we met no one who performed any obvious leadership function, and apparently it was nobody’s job to question us. More and more I sensed that I was part of a vast social ooze, a blindly instinctive slippage down the world’s flank. Defeat had partially stunned the Gonomong psyche. I remarked on this to Vic, and he suggested that it was probably worse for them this time round, compared with the last few such clashes in recorded history: their periodic invasions of the North, their “Rip-Migs”, did not commonly climb so far as Latitude 60. It had been Topland’s state of relative confusion following the Awakening from the Dream of Earth that had tempted our southern foes into mounting their ambitious attack – and in doing so they had underestimated us. The shock of the blow we dealt them at Neydio had knocked out their collective will. They could do nothing but slump back to their own land.

Except – they did have something to show for their great effort. They had taken prisoners. Slaves.

“Thinning up ahead,” murmured Vic.

Emptier stretches, more of them and wider, opened to each side and in front of us. One particular lane, an avenue through woodland bearing to our right, looked the most inviting. We could ride along it fast enough to overtake the forward component of the migration. I swerved Ydrad that way.

“Worth a try,” agreed Vic aloud.

We urged our mounts to increase their speed with the result that we seemed to tear ahead in a reckless plunge down-Slope towards the southern skyline itself, and the thought came to me that the battle of Neydio had not only stunned the Gonomong, it had concussed something in me, too; my psychological brakes hardly worked any more. We “galloped”, if I may use the term, through those acres of woodland, and when we emerged on the other side of them, onto a huger area of bare Slope, we thought at first that we had lost the Gonomong altogether. Apparently empty of active life, the tilted landscape brooded in silence around us until, maybe two miles west-south-west, something like a moving stain came into view from behind another grove of trees. Sunlight glanced off the tips of hooked poles held vertical in the hands of a compact group of riders.

We aimed our field-glasses and as the group leaped into close-up I saw it was perhaps forty or fifty in number. As we watched, the riders lowered their poles till they pointed straight ahead, like spears held at rest.

I thought aloud, “Are they going to charge?”

“Doubt it,” said Vic. “No opponent, as far as I can see. Guess they’re restless – and now they’ve got room to gallop.”

“Well, let’s canter after them,” I replied, with only a brief smile at the hard-to-avoid horsy vocabulary.

We had to be careful not to go too fast because, as we spoke, a few hundred yards to either side of us, fragments of the main horde, which we had outdistanced, came once more into view. We needed to keep our position out in front of them and increase our lead gradually, to avoid suspicion and at the same time not to lose track of the lone group far ahead, which, we assumed, must be the unit guarding the prisoners.

We were helped, in the hours that followed, by the fact that the entire horde appeared to be disintegrating, as it spilled over much larger tracts of country than before. Our guess was that their supplies were running low and their need to forage thus became more urgent. Perhaps also their need to stick together decreased as the distance from their Upland enemy increased. That was good news for us in one way; in another way it was a sad reminder of the ever-heightening Slope accumulating at our rear, separating us more and more from our homeland at the top of the world.

I held onto one cheerful thought. The idea of freeing the captives didn’t appear quite so crazy now. Comparatively, fifty or so unsuspecting warders, out of sight of the rest of the Gonomong, seemed a less hugely impossible proposition...

As we edged further towards catching up with the “warders”, an important change occurred in our environment. We began to note some indications that people lived in this land. Through binoculars we espied the first houses and cultivated areas that we had seen in these severely sloping latitudes. As yet, dwellings were rare and solitary, but without a doubt we were emerging from the “Debatable Land” which had been fought over so often that no one wanted to live there, and we were entering the fringe of Slantland’s more settled country.

“No sign of any natives,” said Vic. “Guess they’re in hiding.”

“In their shoes, so would I be.”

We passed trampled fields, orchards with broken trees, houses with windows smashed and doors off hinges, but the evidence of plunder was not accompanied by any signs of burning. Vic murmured, “Hardly the wake of Sherman’s march... nevertheless, those houses bother me.”

“The houses?” I echoed. “Yes, most of them are damaged. Fences down, too.”

“Take another squint. Forget about war damage.”

My thoughts plodded. “Er... In ground-plan they seem most often to be a kind of kite shape. Diamond, lozenge, whatever. So they’ve got their own style...but then, that’s what you’d expect. They look like quite fine houses to me.”

“Keep telling me I’m wrong – I like it.”

An ambition (that frequently seized me in Uncle’s presence) to say something intelligent, made me chew at the problem as we rode, until at last I crunched on something. “Their alignment.”

“Go on.”

“None of their walls face squarely north.”

“You got it.”

Always, the part of a building that pointed north was the corner between two walls. Always a sharp edge, never a flatness, faced up-Slope.

“And so?” I said. “What are you getting at? Are you wondering if maybe they’re little fortresses, built to deflect cannon fire from Upland? Not very likely, I’d say.”

“No,” agreed Vic. “They’re only farmhouses. So go on – think it through.”

“Right then – I will – so the question is: if I were an architect building at this latitude, what would I need to guard against...” My voice trailed off.

“Heavy loose stuff,” prompted Vic. “Anything that rolls.”

Yes –

My imagination tingled at the mind-set which must pervade southern culture – at the logic of its dread. The truths of mass and momentum. Big things rolling down a Slope that never ends.

Weights that smash down from the north.

“Kerunk,” I murmured, and then the significance of that common expletive finally reached my understanding after its age-long climb from mouth to mouth, folklore echoing all the way up from the depths of lowest Slantland. A harsh truth wrapped in a curse: Kerunk = smash, crush; a long-distance message from the suffering south.

Already, where we were, the gradient must be well over thirty degrees, with loose mass a considerable threat. This must affect every aspect of life, architecture being a case in point, especially if what we saw here was the result of traditions emanating from regions still further down, steeper even than this. The more you descend, the more the ground tilts, the more life must be conditioned by fear of any considerable mass that can slip and hurtle down a worldwide Slope which becomes ever more extreme, and therefore any builder must want to make sure that if the worst happens his edifice will only be struck a glancing blow.

Hence all walls were oblique to the North.

“Typical, eh?” sympathised Vic. “Infested with krunking omens, this place is.”

I silently agreed. Another detail had caught my eye.

As best I can describe it, the typical Slantlander roof was shaped like a hunched-over spine. Aligned like the two up-slope walls, with an edge to deflect impacts from the north, the roof in addition then curved up and over. It was as if it must also defend against projectiles from the sky.

Yes – these houses were cringing. They didn’t so much stand as crouch on the Slope.

I had sometimes wondered, back in Upland and Topland, why there should be a need for sloping roofs at all in a land where it hardly ever seemed to rain. I had supposed that the answer must lie in the influence of the dream of Earth. But that explanation wouldn’t do here. These Slantland designs did not resemble any style that I had noticed in my former world. As for what their cause might be... No. I was in no hurry to become enlightened.

Vic broke into my thoughts. “Duncan, look, over there; don’t point.”

A man was standing motionless in what looked to be a maize field. His proportions were those of an ordinary human being, rather than the thick-limbed Gonomong, so we classed him immediately as a native farmer of Slantland. Surging down-slope towards him, their steeds trampling the corn, rode a score of figures who definitely were Gonomong.

We rode on, we did not dare stop, but we had to watch.

The riders took up position around the farmer and by the looks of it words were exchanged, doubtless in some pidgin tongue, supplemented by gesticulation. I could imagine the farmer saying, “You took so much on the way up, now you want more on the way down, and what will be left for me?” On the other hand, it is possible that he was not a sturdy resister but a collaborator in trouble with his overlords. I noted that his field had been left in better condition than most; the house at its lower end looked undamaged.

At any rate, one of the Gonomong stooped in his saddle, and I witnessed the swipe of the over-muscled arm. The farmer fell like a scythed grass-blade; the riders then took off towards the house and charged past it, yelling. In a minute their whoops had died away and they themselves had dwindled down-Slope, while their echoes settled nauseously in my stomach. A woman and four children appeared at the door of the house, glanced about, stepped out, trudged to where the body lay motionless. They stooped, lifted it...

Vic must have seen a boiling look in my eye. He shouted at me and when I hunched as if to charge south he moved first and grabbed my arm.

He said, “Cool it, will you? There’s nothing we can do. Besides…”

“Besides, what?” I jabbed out the words, but at the same time I allowed him to restrain me, in fact I would not have moved any great distance even if he had not caught hold of me – I was suddenly awash with the shameful truth that I would have stopped anyway, after a few yards. My attitude had been make-believe, for, really, I knew better than to act tough. More Gonomong had approached, were now crossing an adjacent field... Disguise or no disguise, it would be crazy to draw attention to ourselves.

“Besides,” he answered, “you know what our mission is now.”

In my embarrassment I repeated, “I didn’t ask for this. I didn’t ask for this.”

“What?”

“I can’t be accused of seeking this path. Hey, you know...”

“No, I don’t know,” he said kindly. “Tell me.”

“I reckon I’d go crazy if... if I had a choice,” I murmured.

He quietly continued to grip my arm.

A bit later I muttered to myself, “Uncle’s silent. He agrees.” He understands. No retreat. Fate has drafted us, pitifully outnumbered though we are. In compensation, we can pursue private war with a clear conscience.

We could now be as sneaky and as unofficial as we liked. Our evolution from commissioned scouts to self-appointed rescuers was complete.

This cheered me up – this big, close-up aim. And if, beyond such conscious purpose, I also sensed a cloudy, ultimate aim, the lure of that hungry horizon which beckoned us downward for vastly different reasons – well, why worry what The Slant might be up to, so long as it kept me on the go?

*

We continued to edge closer to the group which we assumed was the escort for the prisoners. The rest of the dissipating horde fell further behind us.

I turned and said abruptly to Vic, “Hey! What about your motives?”

“Hm?” He threw me another of his mildly quizzical glances.

Though my words sounded rude in my own ears, I stuck to what I wanted to ask:

“You haven’t really told me why you’re going on and on. What keeps you on this jaunt? Or don’t you really know, yourself?”

I knew that part of it was that he wanted to look after me, I had to credit him with some affection for me, but I had never believed that to be his main reason for risking his life on a mission such as this.

He wasn’t answering... I reproved myself: Duncan, you blundering idiot, you don’t ask a magician to reveal his tricks.

At last, however, he did speak.

“If you can be daft, why can’t I?”

“Is that all I’m going to get out of you?” I demanded.

No answer for another while; then, in a reflective tone: “Everyone has the right to seek what he’s lost.”

“What do you mean, Uncle?”

“Ease,” he shrugged.

“‘Ease’? You’re going in the wrong direction for that!”

“Ease for heartache, if you must know.”

“No!” I cried, “you’re mad! You won’t find her that way!” For all of a sudden it was as clear as if I could read his mind, that he was thinking he might find Aunt Reen hidden somewhere in these southern latitudes, just because he had not found her anywhere in the north. Crazy! Didn’t he understand the size of the world? Did he suppose that there was a kind of cosmic law which ensured that the love of your life was never permanently lost?

Vic sounded quite comfortable as he replied, “Let me be the judge of what I undertake.”

“All right.” What else could I do, but agree? Anyhow, what was I so concerned about? He was the wise guy, after all. I had never known him to be at a loss as to what to do, in any situation. The pity I had momentarily felt for him was ludicrously misplaced. Neither need I feel guilt at having drawn him down into danger with me, since clearly he had joined the expedition for his own vast purposes.

If he thought he could achieve the impossible, let him try.

In fact the idea quite cheered me, and as it happened, during the hours that followed, I needed all the cheer I could get, for it seemed that we had failed in our efforts to shadow the “warders”. Perhaps through our own carelessness, perhaps through the variations of cover (it was impossible for us to keep them in sight all the time) they increased their lead until they disappeared from view, leaving me to stare blankly down-slope with an emptiness in my heart, a sense of having lost my purpose.

Here we were, far into Slantland, quite cut off from any area known to the authorities back home; what could we hope to achieve? Why, exactly, did we not turn back? Again that question. Again, no answer presented itself. I did not understand, or at least could not put into satisfactory words, the reason for our continuation southwards, and when I murmured, “Why are we doing this?” – I did not expect to hear a reply.

My companion, however, spoke: “Because we’re heroes.”

“Very funny. You know, Uncle, I wish you’d wipe that smile off your face. It’s making me nervous.”

“Ah, but first, just let me define ‘hero’, will you?”

“Go on, let’s have it.”

“A lazy lump who finds it easier to go down than up.”

Well, at least that preserved the notion that we were acting according to our own wills. Lazy wills, perhaps, but at least they were our own. I allowed myself a vestigial smile.

But then what happens later, when the Slope has become a lot, lot steeper –

When what is now scarcely thinkable becomes everyday –

I sighed. “Trouble is, the lazy-hero option won’t last.”

“How right you are, lad. So what do you suggest?”

“Pick what we can, while we can.”

“Any chance you can tell me what you mean by that?”

“I don’t blazing well know!” I snapped. “I’m not responsible for what my krunking subconscious says! Actually, no, sorry, I think I do know.” I reflected a while. “You know how special-forces people like the SAS were trained to live off the land, taught to recognize and gather whatever berries, nuts, edible roots and leaves and fungi and so on were ready to hand; well, apply that to morale. We must learn to grab anything which can sustain us that way. Somewhere along the line, you see, we went and made a dreadful decision, and now we can’t alter course; The Slant is seeing to it that we must go through with it; but though we can’t waver, we can make sure we pick what sustenance we find, along the way.”

“Oh, quite,” approved Vic. “Be positive – as the proton advised the electron.”

“What I’d appreciate,” I mused, “is a few uneventful days.”

*

For the next five days my wish was granted. We saw no more Gonomong, and Vic wasn’t surprised. “Looks like they’re avoiding the mistake that Napoleon made on his retreat from Moscow,” he commented. “They’re sensible enough not to go back over the same ground that they plundered on the way out.”

We, by contrast, decided to keep more or less to the Wayline, the broad beaten track which marked longitude zero. For the time being we might have lost sight of the “warders”, but we could hope that our course continued broadly parallel to theirs.

These were calm days, when we had nothing to do but ride, and take readings using the type of sextant provided by Professor Brudenell, which measured the declination of the sagorizon, and hence our latitude and the average gradient of the ground. We made scrupulous notes of the readings in a little logbook which the Professor had provided. During breaks I scribbled a summary of our voyage so far. I felt proud and elated to be an explorer, and as for our rescue mission, that would doubtless regain priority some time, when the current motive got tired, so that one way or another the torch would pass from reason to reason and we would be kept going down, down, down...

*

We Uplanders knew next to nothing about the lower latitudes of the northern hemisphere; “Slantland” was to us hardly more than a name. It seemed worthwhile to wonder:

Might we find allies?

Our hopes increased with the signs of population; it seemed reasonable to suspect that we were gradually making our way down into a belt of civilization that lay across Slantland. Eventually, with a bit of luck, we might well come across an authority that would be pleased to help us against the common enemy. If we could communicate, that is.

“Do you reckon people speak English around here?” I asked.

“By all accounts, they do, at least around the Wayline. It’s one of the few facts known about this slice of Kroth.”

Vic and I debated at length how best to introduce ourselves to the natives if and when the time seemed ripe. Meantime, however – not yet having made up our minds – whenever we came across settlements which lay across or beside the Wayline, we swerved to avoid them.

Logically, since “my enemy’s enemy is my friend”, the Slantlanders ought to be our allies against the foe who had trampled across their country on the way to invading ours. On the other hand, appearances counted against us. We rode the enemy’s steeds. Could we expect the locals to trust us? And when the dried rations in our saddlebags ran out, where might we turn, and what reception would we get?

After the end of the five quiet days came an answer.

*

I awoke – and gargled in shock. I could not raise my head. Cold metal pressed at my throat. I stared up the length of a handle.

The slab-cheeked, black-bearded fellow who held the pitchfork need only give a slight thrust and... Fear, abject helpless fear, slopped inside me. It was worse than anything I had experienced in battle, where I had fought prepared and in a line of comrades. Here, without warning, and without possible countermove, loomed throat-skewering death –

“Come off it,” boomed the voice of Vic somewhere to one side, “do we look like Gonomong?”

From beyond the pitchfork handle a reply grated: “You might belong to their ruling class.”

“What? What’s that supposed – ”

“You might be Prince Nostemb himself. Gonomong princes look more human than the others.”

“Interesting,” sneered Vic. “And would Gonomong royals bivouac alone?”

(I wished I could move my head to see him; he was putting up so much better a show than I.)

“If you’re not Monghees,” came the tight riposte, “how did you tame the ninghestu?”

Growls of support from companions of the speaker accompanied a quiver in the metal against my skin. The fork-wielder had jerked his head, presumably in the direction of where the decapods grazed, to emphasize his point, and the spear-point jerked in consequence. Vic, win this one, please, I silently implored. That last question is a killer. Go on, answer it and make sure you impress them. How did we tame the ‘ninghestu’?

“It can be done,” my uncle coolly replied, “by those who are immune to the fear of them.”

I could exactly picture the imperious smile on his face, and could only hope it would not enrage the man who held a fork at his throat. “Specifically,” Vic went on, “those who are fortified by the Dream of Earth.”

The prong drew back an inch or two from me. I was able to move my head. I could see and count: eight hefty figures around us, armed with a selection of forks, axes and goads.

“The Dream of Earth,” rumbled their leader. “Yes, that means something – to us. But,” he gave a happy sigh, “not to the Gonomong.” The speaker relaxed his stance and retracted the fork further, releasing me altogether and smiling in sudden friendliness.

I rubbed my throat in a daze of relief, while the man also gestured to one of his henchmen, whereupon Vic was released likewise. Just like that, the scene was transformed, although the sticky aftermath of terror still glued my lips. In the hope that he’d do something to confirm the welcome turn of events, I looked to my companion for guidance.

“Ah,” beamed Vic, “it was so good of you not to kill us, Mr...”

“I am Stu Gurrer, headman of Jummudge. And you are…?”

“Victor Chandler and my nephew Duncan Wemyss, of Savaluk, Topland.”

Gurrer exhaled audibly and exchanged awed glances with his men. “I am glad we did not kill you.”

“By way of conversation,” said my uncle in his sweetest voice, “may I add that we have recently fought in battle against the Gonomong. Subsequently we were sent by our government to shadow the enemy’s retreat, and before we proceed on our way we would appreciate any assistance you care to give us on our mission; materials, provisions, information –”

“One big thing I say,” said Gurrer. “You need to stay with us tonight.”

“Why?” asked Vic bluntly.

“You have never been down this far before?”

“No.”

“You know murkburr?”

Vic’s face showed perplexity. “I may have heard the word, but...”

Gurrer turned to me. “And you, Mr Wemyss?”

“I’m all for playing it by ear, Mr Gurrer,” I said, finding my tongue at last, and not caring, for the moment, what murkburr might be, just so long as I had a breather in which I might recapture my stampeded emotions.

Stu Gurrer bowed, turned, and waved at his group to get started. They set off down-Slope as if they expected us to follow without further discussion, and follow we did.

*

“Your hackles are still up, I perceive,” my uncle observed. “You have a sulky look about you.”

“It does seem rather incredible,” I murmured, “that mere minutes after he threatened our lives, we become his invited guests... It was too sudden for my liking.”

Riding behind Stu Gurrer and his bunch, we had struck a path that ran obliquely down between wheat-fields. At the same time a strong breeze had started up, blowing from the south and quivering through the wheat stalks in a way which I did not care for. The peculiar motion made me think of thrumming piano-wires, and worried me like an unwelcome trend in a dream, the more unsettling because I felt wider awake than ever. Danger had roused me to a keener sense of being alive, and to a vibrant pessimism which I must heed.

“Sudden acceptance,” remarked Vic, “is still acceptance. A welcome development, surely? I mean to say... I like the absence of fork at my throat.”

“I still feel it there.”

“Eh?”

“My limitless capacity for distrust,” I explained in the driest of tones, “prompts me to refrain from slobbering with relief.”

“I appreciate that,” Vic smiled at my adoption of his own speaking style. “Yet here we are, riding high on our ninghestu. And down there are Gurrer and his lot, on foot. I like that difference. We up, they down. Makes me feel secure – but no, I see your point. I know, I know,” he continued, arguing with himself. “Fate’s a sneaky devil. Better to anticipate its next jab, than to wallow in euphoria simply because we’ve escaped the last one, eh?”

“Yeah, you’re on my wavelength,” I nodded, “though I’d rather we were both wrong. Now listen – when are you going to check out what a murkburr is?”

He shrugged, “As to that – I’ve managed to recall the meaning of the term. It denotes some kind of storm.”

“Storm? How bad?”

“Can’t say for sure.”

I waited a bit and then remarked, “Well, you certainly seem to be saying as little about it as possible.”

“As you would expect,” he nodded, “with a southern storm. Legend has carried the name, no more, from Slantland to Upland. But we can assume, since the name has travelled so far, that the thing itself is probably serious. So you see, Gurrer was just being decent, offering us shelter, and we’re just being sensible, taking up the offer.”

“Well, in that case – good.”

“Huh – I know that tone of yours. Please, if you’ve got rational doubts, voice them.”

It was all very well for him to ask that, but I could not voice a heaviness. It hung like a static charge in the air about me, a psychic pressure, whether fancied or real, which promised that some glutinous destiny intended to feed us into a crisis at Jummudge. But it was no good trying to explain that, not even to myself. I could only sigh and remark, “No, you don’t learn anything by riding away.”

*

Again the behaviour of the wheat caught my eye. This time it was because the ends of the wheat-stalks were curled back. They were spiralling down to shorten themselves, to become more compact.

By this time our path was skirting a small wood, so that the trees sloped up on our right and the wheat fields sloped down on our left. As the path took us round to the further side of the wood, I counted the log-built houses of Jummudge as they appeared, one after the other, each with its typical humpy Slantland roof, until my count passed three dozen. One structure was much larger than the rest and about fifty yards up-Slope. Beside it lay a heap of unused logs lashed together. I guessed that pile of material was intended to be used to add an extension onto the headman’s house or village hall, or whatever the big building was. I liked this homely sign that ordinary life with its practical concerns must continue.

Stu Gurrer had halted and he turned to raise his deep-set eyes to us.

He rumbled, “Stop where you are.”

This was the predicted moment when my blood expectedly ran cold, although as yet I had no understanding of what was about to happen.

“Dismount,” continued Gurrer to Vic and me, “and tether your ninghestu inside the wood.”

“I understand,” began Vic as he moved to obey, “you don’t want that kind of creature in your village…”

“Hurry,” grunted the headman, and then I understood.

I touched Vic’s sleeve. “Look, down they come,” and I pointed north, to where another path led to the village.

The ten of us had time to take up position just inside the edge of the wood. Vic and I, standing beside the eight swarthy farmers, silently witnessed the Gonomong company riding with their prisoners into Jummudge.

Fifty enemy riders, with a similar number of captives.

“We weren’t sure, until now,” muttered Gurrer to Vic. “We thought they might miss us and choose another village. But now we know.”

I watched a few inhabitants dart into their houses and close their shutters. From the big building, about a dozen people were evicted – men, women and children who ran to take refuge in some of the smaller homes. The enemy encountered no resistance anywhere. Their take-over was as smooth as the ripple of muscle in each gorilla-like arm.

Individual mounted Gonomong took up sentry positions throughout the village, while others undertook the quartering of the prisoners. I goggled at the thought that Elaine was probably in the group which some dismounted Gonomong were shooing into the emptied hall... I could not be sure, one way or another, though I strained my eyes as I tried vainly to spot her until the last of the captives disappeared into the hall.

“That,” nodded Gurrer, “will house the captives during the murkburr.”

“I’m surprised I can’t see more activity,” remarked Vic. “I should have thought that each individual Gonomong would requisition a house, and keep his own prisoner with him during the storm.”

“They scorn to use our houses.”

“But what about the storm?”

“They’ll behave as is their custom: they’ll shelter under the bellies of their ninghestu.” Gurrer spoke with the confidence of a prophet. He looked at us as if to say, quite unmistakably, here your chance will occur. “Do you both see what this means, my northern friends? During the murkburr, the captives will be bunched together and lightly guarded.” When his eye glanced upon me I could read the gleam of faith and that his acceptance of us was conditional, dependent upon fulfilment of that faith. We were the Jummudgeans’ instrument of revenge upon the Gonomong, and no doubt the murkburr was a convenience, an excuse to get us to stay and attack under cover of the storm.

In a flash I pictured my life, melted down, poured into the mould of their expectations, and I told myself that if I wanted to avoid disaster I must crack that mould before it was too late. Disaster, yes – for what they demanded was the impossible. Sure, these Slantlander peasants had it all worked out to their own satisfaction, but they’d find out, when it was too late, that it wasn’t enough to assemble the ingredients for a miracle and simply expect us to perform it when the moment came...

Unless – Perhaps we were being offered our big chance. Perhaps this murkburr would disable the enemy more than it disabled us.

Not very likely! If the peril came from the south, the enemy would be used to it. Wasn’t it obvious that they’d be able to tough it out well enough? They didn’t even need housing as shelter from the storm. It was we who were at a disadvantage. The whole idea of an attack on them was mad, hopeless.

Only, it might be even more dangerous to say so.

*

The day wore on, as we waited in the wood. My thoughts went round in futile circles, and I could not break out of them by conferring with my uncle, for he chose not to excite suspicion by private talks with me. He, evidently, had reached the same conclusion as I. We were dealing with a powder keg of fanatical belief. One false move and the pitchforks would be back at our throats. The threat was not explicit, it was not provable, we derived it only from tones and expressions and the tension in the atmosphere, but, all in all, it was clear.

Nevertheless, now and then I did wonder why we did not simply ride away. But that’s all I did – I merely wondered. And postponed decision. Drifted down the river of Time, towards the rapids of evening.

While we waited we sat on benches and munched bread and cheese inside a hut or barn part way along the edge of the wood. The interior was spacious enough for ten of us; it seemed to have been adapted into what seemed like a woodcutters’ cabin, carpenters’ workshop and dormitory.

I checked with Gurrer: “We’re sheltering here overnight, I take it?”

“Better,” he nodded with a twitch of jaw. At this point a rare thing happened: one of his men questioned his leadership, suggesting that it might, in truth, be better if they went back to Jummudge, to share the plight of their people.

Gurrer shook his head and his face went a dull red. “Elders stay clear. That is the rule.”

“But on this occasion...”

Now the headman’s glower flared into incandescence as he positively speared the dissident farmer with a look of fury, glossed with the words, “We cannot desert our northern friends!”

I looked to Vic; he just assumed his best courtly style and gave forth: “We applaud the discernment by which you have understood that we are friends...”

Gurrer bowed his head. “Toplander words – Toplander deeds. Any humans who can swipe the Thick-Arms’ steeds are surely friends of ours.”

So our decapods, our ninghestu, instead of being a problem for us, were now transformed into a ticket to social success. They were proof that we had “put one over” on the hated Gonomong.

I took a little heart from this. I dared to ask: “As a friend may I ask for details about the coming murkburr?”

The headman’s face crumpled into a frustrated expression. “How can I explain to a northerner… The murkburr, the girdle of worms which I guess, sirs, you have not yet seen...”

“Make it plain,” Vic said, brusquely supporting my attempt.

Gurrer spread his arms as if to disclaim all responsibility for the madness of the world. “The winds are twined, wormlike things.”

“Tornadoes?”

“That, sirs, is a word I do not know.”

*

Vic may have had some thoughts which took him close to the truth, but, if so, he did not voice them during that long quiet day.

We might have tried to cross-examine the Jummudgeans further; only, we didn’t. Gurrer was superficially friendly, they were all of them friendly – but would they stay that way if we seemed to be turning yellow?

The evening dragged on while we munched our supper. Tool-racks and wooden walls and floor, without carpet or decoration, gave us nothing to distract our eyes from the large southern window, beyond which the sun swerved westwards till it was out of view behind the roofs of Jummudge.

To the south, as the daylight dimmed, something offensive rose into the sky.

The primitive in me said yaaaargh.

The twirling brush of a mechanical street sweeper is acceptable if I see it whirring at the side of a road. When, however, I see it magnified to stretch across the sky, I can’t put up with it. Vic as usual showed better nerve. He simply said, “Here it comes.” Apparently he was immune to the horror of size and context, whereas to me that storm was a visual assault. The “girdle of worms” foretold to us by Stu Gurrer soared towards us so fast that I barely managed to believe my eyes; what made it worse was that we had never previously experienced much weather of any kind on Kroth. Not a great deal ever happened in the skies of the northlands. The serene blue heaven of Topland and Upland might occasionally show some wisps of thin white cloud, but rain and snow were so rare that I had never yet experienced any; the most that I had known was an occasional morning mist, vapouring up from the ground that was watered by the eternal supply streaming from Nistoom. And now this intrusion... this abomination…

Gurrer said something which I thought at first was crazy. “Come on, Vic and Duncan, out we go! Safe, if you turn back when I tell you. You might never see this again.”

Watch the approach? Really? We might have a half minute to get a view from the edge of the wood. Yes, come to think of it, the dreadful sight was too good to miss. The others were pouring out through the door; I hurriedly joined them. We emerged from the trees and looked south, into the bristling sky.

Now we were faced with the whole arc of furious dark brown, which in half a minute had risen far enough for us to see the clear blue underneath. In another half minute it stretched across the sky from west to east on a scale which you might see if you could somehow stand on Saturn and gazed up at the planet’s ring, except that it wasn’t beautiful but murky, thready, with convoluted boilings.

As yet we heard no sound; it was our eyesight that took the strain. I ought to have endured in manly patience and silence. What can you expect in a new universe, in which your personal space is bound to be invaded now and then with what seems like the mad nonsense of dream? You should stand firm, rather than fall prey to the fear that reality and nightmare have become one and the same. But my mind muttered: I don’t have to take this from you, world. The whole business swelled too fast for me. My choice seemed to be: jump or be jumped! Terror was an expanding bubble –

“Hey, come back you coward!”

It was Gurrer’s voice that tried to stop me. I ignored the shout and ran. I knew I would never forgive myself for this. To run back into the hut before any of the others –

Except that I hadn’t run. I was still standing where I was. My move, and Gurrer’s shout, had been entirely imagination.

Gurrer, as a matter of fact, was looking at me oddly. Had he guessed something?

He spoke to me in a quieter voice than usual: “The murkburr can inspire...”

Inspire one to become crackers, I thought. Inspire one several steps down a road of might-have-been. The thought of what had just happened in my head shook me more than the crisis outside it. What had caused my might-have-been-but-wasn’t? Must be a scientific excuse. Electricity in the air – a special kind of electricity – unique to the peculiar storms of Slantland –

Then footsteps thudded around me and I knew Gurrer must have announced that it was time to go back inside. I turned and ran this time for real, but healthier for my self-respect insofar as I was running for shelter with the others, and in fact was last in, not first.

On the threshold, just before I closed the door, I heard the first sound from the sky.

It was the hiss of some falling object. Then a thwack, in the field. Then more impacts.

I cried out, suddenly remembering, “Ydrad and Gnarre!” But no, our mounts would be all right, I told myself; look at the ninghestu in Jummudge (I could make out where the invaders had chosen to huddle): bunched together in a space between the village hall and the rest of the houses, the armoured decapods were all curled up, each into a tight ball, their heads stuck under their bellies, and with – from what we had been told – their Gonomong riders blanketed underneath.

Another thwack and some magnified hailstone, perhaps eighteen inches across, smashed onto the field close by, the field where the crop, to ready itself for this, had subsided to an ankle-deep carpet of wheat-curls.

“Shut the door, Duncan,” came the gentle command from Gurrer.

I obeyed. I stood by the window and continued to watch.

From what I could see, in a view partly obscured by trees, the cloud-belt was now three quarters of the way to the zenith. I made out detail in its writhing tubes, which contorted second by second, while smoke-hued objects continued to thump down onto the field, to crash into the trees and to drum on our hut’s roof. The upper air began to howl...

Eighteen-inch hailstones, eh? Hmmm… Not good to go out in, but not shuddersome either. This murkburr makes an impressive amount of noise and constitutes a physical threat to anyone who fails to take proper precautions, but I – I reflected –

A light-headed lunacy possessed me. I glared up at the underneath of the cloud-belt. Belt? More like a rug which has had ketchup spilt on it. Yes, the tomato-red rays of the disappearing sun were messing up this sky-sized rug. Under it, a chunk of the world was being suffocated, but hey, I could see some relief on the way: intervals, gaps of thinness like the divisions in the rings of Saturn. I could make use of those. The picture had come to me, of what to do. I thought: I must do it on my own. If I tell Vic he will give all sorts of reasons why I should not. He doesn’t mind trying the impossible himself, but if he were to notice me behaving in such a manner he’d go rational at once. He'd say that the lull won’t be long enough; that I’ll run out of time and be caught.

...An hour had gone by, night had fallen and the others were asleep, it seemed, hypnotised by the drumming and howling racket, except for Gurrer, whose eyes were part-open slits, watching what I was about to do. He approved, else he would surely have woken the others.

The frequency of hailstones presently diminished and I thought: it’s now or never. Exactly how long the lull would last, no way existed to calculate, but I counted on it being a few minutes. I turned the door handle, looked back at those slitty eyes, pushed the door open and stepped out.

I pelted across the field in the direction of Jummudge.

*

The giant hailstones continued to fall during the ‘lull’, only not so frequently. Trusting to luck or statistics, I estimated that I had a reasonable probability of staying alive if I moved fast and acted fast. Conscience, however, delayed me.

I stood, irresolute, beside the roped stack of logs next to the village hall. The muted bombardment of hail continued to thud and whistle around me as I drew my pistol. No one would see me in this dark. Even if they were awake, even if they looked out, I would be unnoticeable to them. I had no opposition at this moment – except that conscience of mine, uneasy at what I was about to do, unable to forget the terrible artificial avalanche of rocks which had won us the Battle of Neydio.

Come to think of it, that atrocity had not been the worst of its kind that could happen. The avalanche had met its natural limit at the barrier of the Vallum, beyond which the boulders could not roll. Yes, the Vallum had stopped the rocks, but what would stop these logs? What could stop them, once I had released them?

“These logs are uneven,” I whispered to salve my conscience, “they are studded with stumps of branches, so if I set them rolling they are sure to get snagged by something or other, sooner or later, and therefore I am not about to become guilty of the crime of crimes, the one great public sin on a sloping world – the creation of an avalanche without limit.”

On that last word I fired the pistol and one of the ropes jerked apart; however, the mass of wood held, and I might still have abandoned the plan but instead I fired at the other rope, and then it was too late to be appalled by what I had done.

Within moments the stack of logs, which had stood taller than I, slumped and clattered away into the night. For a second or two I felt the vibration in the ground as they rolled and slid down the forty-degree Slope, gaining momentum towards my intended victims. If, in this darkness, I had figured right, the main huddled group of Gonomong ninghestu would shortly be impacted. By what proportion would this reduce the odds against me? I might have gained some clue if I had waited, listened, watched for torch-lit evidence of enemy movements, but I could not stick around; the Gonomong survivors would certainly aim their lights towards the scene of the crime, and besides, the lull in the murkburr was coming to an end, the hail intensifying once more, and to save my skin I rushed towards the hall.

I had to switch on my own flashlight, else I would have blundered and delayed in my efforts to find the hall porch. I reached the outer door, wrenched it open and caught hold of the inner door, again aware, as when I had fired at one rope but not yet at the other, that here was a last chance to reconsider. The chance existed only theoretically. I pulled the second door open and stepped into the lamp-lit hall.

Tables and chairs had been moved aside as if to clear the centre of the floor for a dance. Two hulking Gonomong guards, with their backs to me, stood with swords drawn, towering over the fifty or so captives who sat or lay on the cleared space. A third upright man, dressed in blue jacket and trousers with orange braid down the sides of the legs and sleeves, was obviously not a guard, obviously not a rank-and-file Gonomong at all. His arms were of human proportion; in shape and physiognomy he might have passed for an Uplander or an Earthman; he had steel-grey hair swept back and finely carved features, coldly handsome. I had even less liking for the look of him than for the hulks he commanded, but I dared not hesitate in my challenge, for he was in the very act of turning and he carried a gun. He saw me and spoke, but I spoke at the same moment and in a louder voice: “Drop your weapons.”

It ought to have worked. I did, in theory, “have the drop on him” – and my meaning was surely obvious even to one who knew no English (and if this was the Prince Nostemb whom Gurrer had mentioned, I suspected he would know English) – yet instead of obeying me he responded with a contemptuous smile and brought his own gun to bear. Meanwhile the guards looked over their shoulders at me and one of them grunted a question. Their leader answered with a chuckle and I felt the eyes of the captives on me, the forlorn Uplanders whom I had supposedly come to rescue, and I experienced the greatest embarrassment and shame of my life so far, for my bluff had been called and I could not shoot, it had been too late right from the start, I could never have shot this Prince (or whatever he was) in the back, not to mention the two guards; I had started something I could not finish, something which was about to finish me, and I wished I had been born someone else. Not to be a chump: how great that would be. Why doesn’t life co-operate and give a fellow a break –

Ziiing... A snap in my brain.

I shuddered in the dark porch where I still stood. In reality I had not opened the inner door; I had never entered the hall; the humiliation had never happened; the dreadful blunder had not been made. Relief and gratitude surged through every vein in my body as for the second time during this storm I knew that my consciousness had returned from a sprint down the path of might-have-been. The murkburr howled, the building shook, and newer sounds, in addition to the bombardment of hail, namely enemy cries, became distinguishable, but this time around I waited, I stayed where I was. Minutes passed; then the fury of the elements began once more to abate, and I wondered if it was actually all over or if this was just another lull.

The hall door burst open, pinning me behind it. I heard the stream of captives pouring out; not an escape, they were being herded out, impelled by cursing guards. I quickly guessed then that the storm was over and that Prince Nostemb was determined to face what he thought must have been a heavy partisan attack. Perhaps he intended to use the captives as a human shield –

The tramp of boots through the doorway ceased. I peeped from my hiding place, and sidled into the emptied hall only to find that it was not, after all, quite empty. On the floor lay half a dozen inert figures. They were those for whom it had all been too much: the exhausted and the injured, mostly women and children.

Beyond them was the back door. I crossed the floor and opened this. Out that way I saw no lit shape, no certain menace to bar me from the darkness beyond, at least not just then. So in that narrow moment I rushed to one of the figures on the floor, strained and managed to lift her, and carried her out the back way.

Elaine Swinton, though slim, was too tall to be a featherweight; she flopped around me as I panted with the unaccustomed effort of carrying an unconscious girl, and I had no reason to believe that I would get very far. Yet in this triumphant moment I was beyond calculation. Optimistically I chose to hope that Prince Nostemb and his troop had been sufficiently harmed and confused by the avalanche I had unleashed, and that the villagers and their chief would in some fashion seize the opportunity I had given them. I, meanwhile, concentrated all my will upon the need to protect my prize from recapture. I lurched away in order to get us lost in the dark.

*

By starlight I set her down, her body aligned with the Slope, feet southward. I pillowed her head on my rolled-up jacket, and in so doing I put my face close to hers. I wished I dared switch on my torch, while, anxiously by fingertip, I felt her closed eyelids, sensed her ragged breathing. She whimpered; aching with compassion I put my arms around her. In my yearning to get her to safety, I wondered whether I ought to have tried to sneak her into one of the outhouses of the village, or whether it was inevitable that they would all be searched.

A tiny glint told me that her eyes had snapped open.

“Lawrence,” she sobbed, and her arms flew around my neck.

Great. Typical. Pity my name isn’t Lawrence – whoever he is. “Don’t worry, Elaine, don’t worry,” the caring side of me meantime murmured, as I hugged her more tightly.

She uttered a sort of hiccoughing gasp and before I knew it I was being kissed passionately on the mouth. I could hardly believe it. Here was the insipid beauty whom I had half-despised at school, now hotly alive. Probably nothing that had happened to me so far on Kroth was quite so startling as this.

“Elaine… mmmm... I’m not Lawrence, I’m Duncan... mmmmm, I’m Duncan Wemyss...”

In her fervent state my words did not reach her, so I decided that I might as well stand in for the absent Lawrence, for, after all, he wasn’t here, he hadn’t rescued her, whereas I was and I had. The alternative, “scrupulous” course of action would have been to push her away. I wasn’t in the rejection business, especially not then... so I lived in the moment and shamelessly enjoyed the kiss.

But, hey, enough of this: do not exceed recommended dose of passion while on run from Gonomong. I had to persuade her to get up and walk. I drew back from the clinging lips. “Elaine,” I began with maximum seriousness, plus the futile sense that I was merely talking to myself, “listen, please: I’m sorry I know nothing about treating shock, but I do know that we need to put lots more distance between ourselves and Jummudge before daybreak, understand? We must move, and I can’t carry you all the time! Elaine, please, we’ve got to walk, we’ve got to get away.”

To my relief, at last she heard, and scrambled to her feet. I steadied her, she held onto my arm and we began to move down-Slope, obliquely, away from Jummudge.

Soon we had our arms around each other like a courting couple, which helped both of us not to stumble in the dark. The path was uneven, but at least it was a path of sorts and I could not bear to leave it, although logic suggested we’d be safer from search parties if we cut across meadows and fields.

Search parties... that got me thinking... how keen were the Gonomong to recapture every slave? What did the possession of slaves mean to them? Why go so far to get them, anyway? I had seen no evidence that they snatched them from Slantland, only from Upland, thousands of miles above the Gonomong’s equatorial home. It did not make sense – economically.

I speculated, then, about non-economic motives. I had never tried to think it out before.

To own a slave from the far north might be a status symbol. Or again – one might have to consider the possibility – sheer hatred... which in turn made me think, what inferno was I descending into with every step I took? I caught my breath at the idea that this might be like one of those dreams where you can’t stop yourself drifting closer and closer to where you least want to be. Why oh why was I going down-Slope? That perpetual question! Surely, if the aim was to escape the Gonomong, our chances would improve if we turned and climbed northwards.

No – that wasn’t the point: I did have a practical reason for continuing south, namely, that I hadn’t told Vic of any other plan, hadn’t arranged anything with him, so the only hope I had of re-combining our forces was to maintain the approximate course of our journey.

But then why had I attacked at Jummudge without consulting him?

He had been asleep.

Why had I not woken him up?

Because there had been no time for the inevitable argument. So here I was. Taking step after downward step in the company of my monotonous doubts. Responsible for a girl who seemed “not with it”, though to my relief she was able to feel her way over gates and stiles.

Time dragged by and we continued our descent, while I sniffed the night air and kept my ears open for sounds of movement around me, tried in vain to read Elaine’s expression by starlight, and gradually – involuntarily – began to relax.

Once, when I glanced at her profile, I thought she might be looking at me sidelong, which prompted me to murmur her name and ask if she was all right.

“Yes, thank you,” she whispered back. And that was all; no “Lawrence” but no “Duncan” either. I left matters as they were.

Hours later, the sky to our left began to brighten. She was tottering by this time, perhaps too exhausted to notice or care who I was. The dawn light reminded me also of my own weariness and hunger. We had to have shelter, rest, food. I came to a decision. I would approach the next Slantlander farmhouse we came across; no reason why we should not expect hospitality...

Right then I saw the house to aim for: at the corner of a field, where two paths crossed. I did not hesitate much, did not scrutinise the landscape at all carefully for sign of the enemy; I remarked lightheadedly, “We’re just a Slantlander couple on a visit, a rather early morning social call. Come on, Elaine, best foot forward.”

She faltered, now that the end was in sight. “Come on,” I repeated, speaking not only to her but to myself. On we staggered, onto a level-banked path that led to the porch. Then to a door of wooden slats, then lift the hand and knock: these must be the right things to do, for they were the only things to do.

The door opened before I could touch it.

“In, quick,” said a woman’s voice. An arm sleeved with ropey material reached for me. I was drawn across the threshold, and I pulled Elaine after me. The woman turned her attention to Elaine, catching her as she swayed, while a man, dressed like his spouse in a thick-woven gown the colour of mud, motioned me to a wicker chair beside a blazing hearth.

I plonked down and by the light of a couple of oil lamps I bleared at a pan of soup steaming on a gridiron. My eyes dumbly followed the billows of steam.

“What are we to do with you?” the man sighed.

I turned to our hosts. I tried to think. They were a dour-looking couple, unfriendly but honest: that was my immediate impression. And well might they hesitate before harbouring fugitives – yes, I could tell by the way they looked at us, that they knew.

Ah well, that’s that, I thought disjointedly; either they turn us in or they don’t. I relaxed in the warmth of the fire. The man talked; I answered his questions and then, after a while, I wondered how much I had told him. Certainly he now knew the main point, that I and my companion were Uplanders on the run from the Gonomong.

Our hosts served us bowls of the soup – mutton and vegetables – which tasted heavenly. A beautiful future began to gleam in my imagination. Elaine and I would go native, until the Gonomong migration had receded far south of here. Then, after some weeks or months, we could start to make our gradual way back up the Slope to our home in the North. Vic – well, he would please himself with his grand scheme, whatever it was, but Elaine and I would be out of it. Our young lives stretched before us, and I, in rescuing her, had also rescued myself from the reckless plunge toward the hungry southern sagorizon.

I contemplated the heavy faces of the folk who had taken us in. I would be as blunt as they. “Can we stay for a while?” I asked. “Till the hunt, if there is one, dies down?”

The woman said, “It will never ‘die down’.”

The man said, “Ardeha is right. They never give up. They will take your girl back sometime; the only question is how soon.”

Oh kerunk, I had talked too much.

Through clenched teeth I said, “I shall keep her free as long as I can.”

“Stir this,” said the woman, bustling over to the soup pan. “Make yourself useful.” She sat down again and I went to obey. I hoped, as I tended the bubbling mixture, that the chore was a sign that I had been accepted. My hosts had bent their heads together and were muttering – practical arrangements, I trusted. But then the man’s head turned and his expression seemed to fall apart in dismay. My eyes followed the direction of his glance.

Through the window I saw a decapod on the path outside.

Goodbye, golden future.

Simultaneously the front door shook to a blow.

“Jarad, hurry, open it,” pleaded Ardeha.

Jarad did so, and while I stood in frozen panic beside the soup-pan, in swaggered a Gonomong, six and a half feet tall, shirt open down the front, shaggy chest and arms like those of a gorilla, holding a drawn sword. I had a pistol but it if I had tried to draw it I would have been spitted before I could make half the move. Not that I seriously thought of doing so. Gripped in both my hands was a weapon far better, in the circumstances, than any gun. “Don’t touch her,” I yelled at the hulk who was reaching for Elaine as she slumped in her chair. “Don’t touch her or you’ll get this!”

My despair was channelled into the madness of my shout, which must have communicated the truth of my threat. I really was about to splatter the pan’s scalding contents onto my enemy’s head and torso. No mere threat of a bullet could compare with this horror. It appalled friend and foe alike. Ardeha and Jarad shrank away towards the furthest corner of the room, while the Gonomong lifted his arms to protect his face, and so far forgot himself as to open his fingers in so doing. His sword clattered to the floor, and I plunged forward with the one idea that I must pick it up before he recovered his wits. Logically, this was a poor move. I ought to have drawn my pistol then; instead I went for the sword, determined to grip it with both hands and heave it up and brandish it with all my strength to compensate for its size and weight, and in my frenzy I over-compensated. Luckily for me, he was irrational too. He had partially turned his back, and now in furious shame at his momentary cringe he jerked round to face me once more – lurched forward – to impale himself on the up-ripping point of his own sword. His face wobbled as he met death with a distorting yell. The body toppled to the floor, wrenching the sword from my hands.

Panting, swaying, I could not take my eyes off my handiwork.

“You’re dead, you fool,” grated Jarad. “Dead as he is. And so are we. We’re all done for now.”

“Counts as suicide,” I mused.

Jarad advanced and shouted in my face: “You hear me? You’ve killed us all!”

“No, not necessarily,” I replied, focussing my sick stare on him. “Not if I get the body away from here.”

“And how are you going to do that?”

“You’ll see. I’ll arrange it.” I backed towards the open front door.

Jarad coughed with contempt. “Running off won’t do you any good...”