kroth: the drop

2: the jaws of n'skupur

Vic refrained from comment while I lagged moodily out of earshot. He looked back now but though I expect he saw my muttering lips move he asked no questions. He knew when to keep quiet.

I was talking back at Fate, or Life, or The Way Things Are. "All right. All right. All right. Go on, pummel me with events. Or roll 'em out like carpets and then, when I step on them, pull them from under me. But don't complain if you find me too punch-drunk to be appreciative."

No matter what fresh dramas remained on offer, it was going to be a while before I could do more than drift in lackadaisical stupor down-Slope.

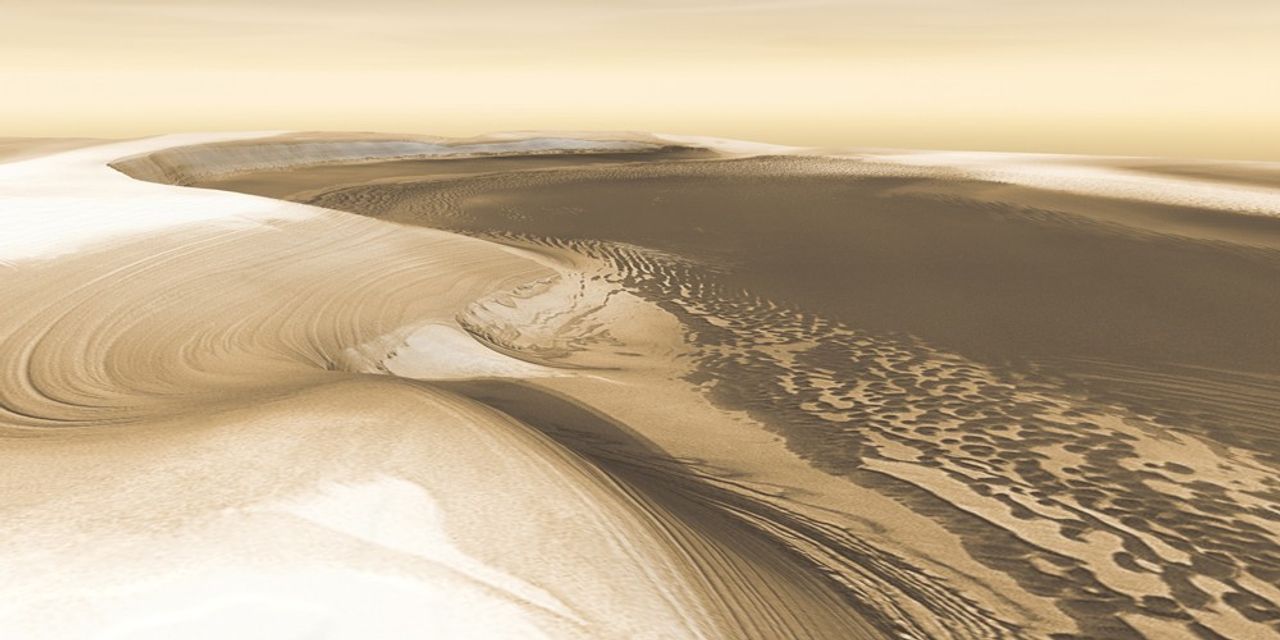

During the next weeks of our descent the ground became more uneven. This was mainly because of an abundance of streams, which obliquely corrugated the landscape. We had to cross their little gullies several times a day. At least, we had to so long as we continued to insist on a straight route downwards, firmly keeping to our course along the pale track of the Wayline, which ran straight due south down the flank of the world at longitude zero. The gullies, anyway, were not a problem; they were easy to cross. Indeed, the inchworm design of our mounts might deliberately have been evolved for such a task.

The streams were welcome to us, for they furnished us with supplies of water and opportunities to wash our change of clothes; we spread our garments to dry on the backs of Ydrad and Gnarre. Routines of this sort gradually introduced a sort of fantastic normality into the journey, while The Slope steepened from forty to fort-five, The Slant protecting our minds from the enormity of it all.

We knew with our brains and our eyes, but not with our guts, what we were doing, where we were going. On a deep level I had given up trying to justify and understand. Superficially, though, I could still play at speculation. Sometimes my tongue was loosened and I could exchange ideas with Vic when he felt inclined. For example with regard to that weird storm, the murkburr, that had hit us at Jummudge: we might never be able to account for it scientifically, but there was no harm in trying.

We decided that any theory must cope with two facts, (1) the

“hailstones” had not fallen straight, had instead hit the Slope at

right-angles, which means they hadn’t simply “fallen” - some force or

other had spat them at the ground; and (2) upon impact they had

disappeared in a puff of dust.

“I reckon,” decided Vic, “that the ‘hail’ must have been composed of

polarised, crystalline air. Or ether as it is sometimes called. Lumps

of the universal medium.”

“Ether? In lumps?” I smiled.

“Yes, abraded by the violence of the Kroth-girdling storm.”

“Oh. And the storm itself – what caused it?”

“That sort of disturbance must be whipped up from time to time by the

close-circling sun. Remember, here the sun is just a satellite.”

“And the way the lumps disappeared upon impact with the ground?”

He had the answer to that too. “It is because the shock of impact

caused the stuff to undergo a ‘phase change’ into normal air.”

I congratulated him. “You’re quite a cook; my mind feels as content

as a satisfied tummy after a meal of your science-jargon.”

“What you’re saying,” he sighed, “is that mumbo-jumbo imparts a sense

of well-being. Well, let it go at that – though I was hoping for more

serious feedback. By the way, look at this.” He showed me a paper

scroll.

I unrolled it and read: The bearer, Vic Chandler, and his nephew

Duncan Wemyss, are friends of Slantland and enemies of the Gonomong.

Please give them all assistance. [signed] Stu Gurrer, Headman of

Jummudge.

“So – we show that in all the other villages, do we?”

“It should get us lodged, or so Gurrer thought.”

The trend, during these dreamlike weeks, was towards larger native

settlements, some big enough to count as proper villages (none, yet, the

size of a town), and often linked by cable-chair. Our signed scroll,

whenever we presented it, did indeed earn us an overnight stay, so that I

became accustomed to a certain degree of comfort at the end of a day’s

riding. More and more frequently our arrival was expected. Then the

first sign of the presence of a village ahead of us would be its

welcoming committee lined across the route, with a messenger already

sliding off by cable to alert the next one of our coming. Not all hosts

were as formal as the folk of Jummudge; quite a few were folksy,

inquisitive, jolly to meet us. We had some real conversations during

feasts given in our honour. We felt obliged to answer all questions as

best we could, and it was fortunate that our hosts were more interested

in our origins that in our aims; they wanted to know about Upland,

Topland, and the battle we had fought in, more than they wanted to know

about our destination, which we ourselves could hardly picture. But we

did hear, vaguely and impressively (because our mastery of the decapods

was the stuff of legend for these folk) that certain other adventurers,

long ago, had equalled our achievement. We heard of deep descents to the

south, surprise attacks, rescues, single combat with Gonomong leaders,

and actual forays into the region of dread known as Udrem. Heroic,

impressionistic legends, these accounts furnished material for much

supper-table chatter before the talk turned, as it always did, to our

lives in Topland.

I do not intend to give the impression that we were travelling in

triumph through a rich and crowded countryside. Rather, each day’s start

promptly engulfed us in solitude. The empty stillness and the

steepening Slope stretched away more often than not with no sign of

Man’s presence except a scarcely visible strung cable swaying in the

wind, or an occasional farmstead showing as a speck in the down-ahead or

to one side in the tilted distance. And always the sky’s under-slung

jaw gaped wider, warning me, that if ever the Slant’s psychological

screen were ruptured, the empty blue must leap to devour my spirit. That

did not happen, yet the pervasive loneliness won out after a time, by

which I mean that we eventually ceased to expect much from the

prosperous villages. We abandoned the hope that they would trend towards

towns and cities. We realized that we were never going to see a

Slantland civilization that might match that of Topland. Our plan to

find effective allies became a mere dream.

Also, our status became blurred in our own minds. Were we agents,

rescuers, any longer? Or were we mere wanderers? Or less than that – a

trickle of matter?

Finally, the agricultural lands petered out altogether. Further weeks

of descent took us into more primitive terrain once more. We had

threaded our way completely through a belt of relative prosperity and

out the other side. Villages, smaller and more widely scattered, no

longer linked by cable, were surrounded not by tilled terraces but at

the most by a few orchards and pastures. The grass was grazed by breeds

of mountain sheep and goats that were quite happy with a slope of over

forty degrees. Also, we began to note some peculiar cattle.

Those critters almost gave me the creeps. To put it another way: when

I first set eyes on them, I found I owed gratitude to the Slant.

Without that essential cast of mind I might have suffered some nasty

reaction to the sight of animals which were so adapted to the Slope that

they could not have stood on level ground. One species had its left

legs almost twice as long as its right. It grazed facing west, while the

other species, similarly asymmetrical but with its right legs longer

than its left, faced east. Thus specialized, they never turned round. To

compensate for that, their markedly long, flexible necks, good eyesight

and agility made it easy for them to move backwards at need, always

cross-Slope, in odd cavorting prances which might well have shunted me

into nightmare, were it not for the Slant’s filter, its providential

barrier between my brain and my guts.

As it was, I managed a chuckle at the lopsided creatures.

*

More days blended into an uncounted stretch of time, though I had an assurance from Vic that he was keeping track of the date.

The old question, “what the heck am I doing?”, ceased to be insistent. Also, I became aware of a long silence from all those religious doubts and attacks on my faith which had clamoured so noisily in the aftermath of the great battle at Neydio. I could recall them, but their noise was stilled by the quiet waltz of world and sky, so that it seemed ridiculous for me to have high-flown doubts or opinions of any kind. The occasional smudgy sight of a distant, minor murkburr – far less alarming than the one which hit us at Jummudge – also encouraged me to refrain from inner comment on the meaning of it all. Might as well go with the flow, thought I. Or does a wind-blown leaf need to understand the currents that waft it along? Yet, every now and then the bright little idea would bob up:

Would it not be sensible to set some limit to our expedition?

I skirted the shoals of alarm, from which the wrecking thought Why? shone occasionally through the fog of habit. It felt natural just to go on and on. I was in a state of acceptance of a journey which now seemed an end in itself. This attitude was sculpted, and my character adapted, as surely as the legs of those strange cattle had grown slope-fitted through thousands of generations of evolution. Only, with me the adjustment had happened more quickly, because the human brain’s outlook mutates much faster – “And so it should,” thought I. Did it not make good sense to pay the price I was paying for peace? Matters were being taken care of, every objection blended into contentment’s soupy swirl...

Nevertheless the “soup” at last went lumpy.

The sun had just slid behind the Slope to close an evening which marked the end of the third day since we had seen any sign of human life. I fount it reasonable to wonder: were we approaching the southern limit of humanity? (Ordinary humanity. The Gonomong were a different matter.)

I called out to the hunched figure some yards away. “I say, Uncle.”

A snappy voice answered, “Yes? What?”

“Er – the sun’s just set...”

“Really? Well, well!”

Try again, I told myself. Marshal your thoughts before you open your mouth. He doesn’t like waffle.

“What I mean is – This time, I really saw what I was looking at.”

I waited for more grumpiness, which my dull words had deserved.

But no. A sharp little movement and Vic’s face turned in the gloom.

“You got what to say about the sun?” He sounded interested now.

I waved a fist. “It’s not what I say, it’s the way I say it! Kerunk – why does it take my brain so long to see things properly as they are? Every blinking day I’ve kept on with the old Earth words ‘sunrise’ and ‘sunset’ as though the sun really does go up and down, when actually, it never does go either ‘up’ or ‘down’, it just pokes out and in, as it whirls around us like a ball on a string – no ‘up and down’ about it, it zooms across our line of sight. Of course it does; it has to! We’re on krunking Kroth, not Earth! Phew – what’s wrong with my wits?”

Vic encouraged me with a slow nod which I could just about discern in the gloom.

I drew a noisy breath. “It’s a hell of a shock,” I grumbled on, “knowing that I can look at a thing for months and use entirely the wrong words for it. Makes me wonder what else I’m overlooking...” I heaved another furious sigh. “Ah well, for what it’s worth, this, from now on, is my – er – acknowledgement of what the sun does: in the morning it pokes out from behind the eastern Slope, it then travels round, horizontally, and at the end of the day it pops out of sight behind the western Slope. That’s all. It never ‘rises’ or ‘sets’. It just swings round on a level path. It traces where the horizon would be, if we had one.”

“And you’re annoyed,” came the response.

“Yes! Because it’s been this way all along and I’ve only just admitted it!”

“Quite, quite. I, however, assess your point differently.”

“You do, eh?”

“For the best of reasons – I see its good side. I’m actually relieved that you’ve told me all this. Extremely relieved; it’s more important than you realize. Uh... perhaps you’d noticed... I’d grown more sarcastic recently?”

“Er –”

“I was worried about you – and me – sinking into trance-like acceptance of our descent into the unknown.” His voice gathered power: “And yet I dared not do anything because, after all, how am I to know we’re not right to turn into unquestioning zombies? But now you’ve shown that in you survives the all-important ability to receive a jolt of surprise. That looks good to me. Good for both of us that you surprised me. Good that we’re still surprisable.”

“Nice of you to say we and us. Sharing the responsibility.”

“Tact,” he said, and I could imagine him smiling in the dimness, “is one of my unrecognized virtues.”

Tact, indeed yes. The vulnerability he pretended to share, the danger he pretended to face alongside me, was most likely mine alone. I very much doubted whether any force on Kroth could turn Vic’s indestructible ego into that of a “zombie”. Well, so be it. I was the weaker party, but still I had pulled through – so far – though the ‘zombie’ problem, the adaptation problem, would doubtless recur...

We sat in companionable silence as we watched the sky in front of us darken. I nursed the happy thought that my effort to speak had been worthwhile. I had said something which had pleased the big brain himself.

Indeed, he returned to the subject after a few minutes. “Talk about breaking the ice – the ice that creeps and chills: that killer, adaptation: before you know where you are you no longer have eyes or mind of your own, you’re just a spokesman for the scene, blind as a bat, dumb as an oyster. But not us, eh? If I had a champagne bottle I’d uncork it now.”

I began, “Good thing The Slant left me some latitude –”

“Latitude!” he yelled. “Hey, that’s good!” The loudness of his laugh showed that he really had been worried. “Go on,” he encouraged.

I made a supreme effort to corral the right words. “The fact that I’m not cocooned in all directions... the fact that I’m not completely tied up, muffled, swaddled by acceptance of goodness-knows-krunking-what... let that stand for champagne.”

“Latitude,” he repeated in a growl. “Forty-five degrees of it now.”

We were sitting on little outcrops of stone with the heels of our boots resting on the grass slope. Our steeds were dim mounds to one side. Further off were some rocky irregularities, minor projections jutting from the overwhelming diagonal slash between ground and sky. I thought back to how dizzy I would have been if, in England, I had got onto the sloping roof of my house. By eerie coincidence, Vic continued: “I should get a job as a roofing expert, if I ever find myself back on Earth.”

Yet the comparison was pitifully inadequate. The stars... they shone in front of me all the way down, down, so brilliantly down down down; so many of them twinkling below me! Nor could I pretend that they were mere reflections in some calm sea, for those underneath the celestial equator had patterns of their own – proof that Space had taken a bite out of what should have been ground. This emptiness yawns for real. So screeched the ghost of my old Earth self.

“To stay awake as me, I’m playing a dangerous little game here,” I remarked.

“Which one?”

“Using fear to counteract Slant-dope.”

“Like – set a thief to catch a thief.”

“Sort of,” I agreed. “I’ve got bags of suppressed fear. I’ve just let out a little controlled whiff of the stuff to – er –”

“To temper The Slant,” grunted Vic. “To keep awake, as you put it. Yep. I’ve done likewise. Fear as a rheostat – you’re right to call it a dangerous game. Perhaps you only win if you don’t talk about it too much.”|

Disregarding that, I went on murmuring, “The fear works better at night. By day it tends to get buried under false reassurance, because you can still pretend – just about – that you’re on a huge mountain and that somewhere down below, beyond the haze, there’s a normal plain, so that the Slope doesn’t really go on forever, it’s just that it’s so vast that the air between us and its base must have become opaquely blue... But you can’t fool yourself that way at night. To see stars below where the horizon ought to be... that’s not a horizon, that’s a sagging open mouth with stars in its gullet...”

“I’d close that valve,” interrupted Vic.

“Valve?”

“Cut off the fear-flow. Now.”

“Done.” I spoke curtly.

“Well done. You were going good, but enough is enough. Nevertheless,” he continued, his voice full of warm respect, “I don’t doubt that it’s a smart idea to look at the night sky. If you do it right, that is. Yes,” he went on, “if you do it right, it’ll help the balance which you’re trying to achieve.”

“The balance,” I supplied, “between dopey adaptation to, and terrified awareness of, the sagorizon.” He nodded, and I felt the rare glow of our intellectual rapport.

“And this is how you do it,” he continued our duet of ideas. “Stare at the sky, but without reminding yourself of its relation with the ground. Instead, forget the ground.”

“Forget the ground? What do you mean?”

“Forget the world. Imagine you’re sitting on the nose of a starship.”

“Ah... as if I’m out in space.”

“Well, aren’t we all? And this is straight science-fiction, a recognized theme, safely stupendous. Not unsettling, not weird; just comfortably awesome.”

“Very well.” I put some effort into imagining that I was sitting in a glass blister on the nose of a world-sized starship. Space all around: yes of course, in a way it was true. Spread out before me the stars were shining to co-operate with the idea.

It was a promising trick, although intellectually I knew that if I somehow stepped away from this “starship” I would not float off, I would plummet forever in a universe with a real up and down.

Never mind that objection, I’m only pretending, and besides, I’m a long way from the edge, so there’s no way I can fall off from here. Use appearances to fiddle with the rheostat of fear! Adjust it to a gradually higher setting by abandoning this or that illusion, always keeping control –

Unfortunately, appearances aren’t always completely co-operative.

The first snag occurred when I noticed that the equatorial stars were on average just a little blurred.

It wasn’t very obvious but if you looked at the sky as a whole for a few minutes you began to feel sure that Kroth’s firmament was encircled by a belt of slightly fuzzy stars. My eyes began to water from staring at them.

I described aloud what I could see, and added, “Does this mean there’s a kind of extra thick air-belt round Kroth’s equator?”

“No, it’s nothing to do with our atmosphere. It’s a real deep-space phenomenon.”

“So you know about it – Krunking heavens!” I interrupted myself as I noticed something that temporarily diverted me from the fuzzy-star problem.

“What’s up?”

“Here I go again, missing the obvious! No sign of any Milky Way!”

“Correct. That’s because there’s no grouping of stars into galaxies, in this smaller universe.”

That word smaller quietened me.

I remembered those hikes in Topland when I had gazed at the sky and pondered the paradox: ‘small’ makes huge. Smallness shrinks the room, invites you to touch the wall; smallness sneaks the ultimate close. So yes, the Krothan stars are merely millions, not trillions, of miles away, but millions out-power trillions if the trillions are merely weightless while the millions are vertiginous; those “lesser” millions, if you look up at them, really tower, whereas on Earth “up” and “down” are points of view that cannot loom, can only trickle away into a mere infinity, awesome but not immediate, unlike here... here where smallness is a snuggly touch of relatively intimate “mere” millions of miles that you could actually, personally, fall. And during the descent towards the fall-off point at the waist of Kroth, emotional connectivity makes each mile count! All of a sudden I was groping for some mental dial to adjust and moderate the awareness… And at that tricky moment I noticed a change in the sky.

A star winked out.

“Uncle, did you see that?”

“What?”

“One of the fuzzy equatorial stars – it just disappeared.”

“So? There’ve been many of those eclipses.”

I mopped my brow and remembered. Yes, come to think of it, those equatorial stars did often wink off – or wink on – each star having its own hour and minute, the same time every night. But that didn’t help at all, because this was yet another of those occasions when I had to admit I had seen something again and again without noticing it properly. It meant I now had to catch up on a lot of wonder. How could I have been so dopey, so obtuse?

“It can’t be clouds, can it?”

“Nope. No obscuration.”

“What rubbish I talk. I didn’t think.”

“Here.” Vic held the binoculars out to me.

I reached for them, raised them to my eyes, and fumbled with the focus. Here was my personal introduction to Krothan astronomy. I anticipated that it was going to be hard to take. The images jerked about as I tried to hold the glasses steady. I glimpsed what could be described as brilliant little upside-down exclamation marks, the long bits considerably less bright than the dots from which they dangled. Or another way I could say it was that I saw stars with little goatee beards, dangling vertically. Faint though the “beards” were, the fact that they were visible at all, millions of miles off, meant that they must be the material cause of the stars’ naked-eye blurriness.

“Comets?” I asked, but I knew I wasn’t seeing comets. Aligned as they were, so neatly around the celestial equator, they couldn’t be comets. In fact the chances were that this universe did not have comets, or asteroids.

So what was going on? Something I did not care for at all. The confidence which I lacked in what my eyes saw had nothing to do with any doubt of its reality. It was real, all right; real but not reliable; I didn’t trust it not to turn bad on me. You get these hunches sometimes in dreams when some dream-reflex warns you that you’re in for it.

“In any universe,” Vic lectured, “a star can be defined as a natural fusion reactor. It blazes away, emitting its own light, far brighter than a planet, which can shine only by reflection. But you need to remember that the roles of stars and planets are reversed, here in Kroth’s universe, from what they were in Earth’s. In that respect Ptolemy would have been right, and Copernicus wrong, on Kroth. Stars, here, are only satellites of their planets; extra-brilliant satellites, to be sure, but still much smaller and less massive than the worlds they orbit. So when, from our viewpoint, a star passes behind its planet, its light is totally eclipsed for many hours. Unsurprisingly, then, not a night goes by without you seeing some equatorial stars wink off and some wink on.

“These eclipses gave Man his first piece of naked-eye evidence for the existence of other planets, long before telescopes were invented, for ancient Krothan sages deduced they must be witnessing the occultation of stars by worlds...”

I felt soothed by the flow of explanation. I might have been quite lulled, it all sounded so obvious and reasonable, but for the fact that I knew my uncle well, knew that to be soothed meant eventually to get socked. And since that reckoning awaited me for sure, I could do nothing to avert it. I simply continued, therefore, to peer through the lenses, allowing my sight to rove while Vic’s speech glided towards his punch line:

“Another piece of evidence is borderline-visible to the naked eye. You can guess what I’m referring to – the blur, the ‘fuzz’. Its nature becomes obvious with binoculars, which don’t have the magnification to resolve a planet’s disc but which do give you quite a good view of the debris-fall from its southern hemisphere...”

Advice for the traveller: that sly weight on the stomach, that twitch or blench of phoney astonishment at a fact you must already have known – you soon get over it. It leaves you aghast, but not really shocked. You see, same as I saw, that in a universe where every single thing must fall unless it rests upon (or is attached to, or possesses) the mass of a world, stuff must always be dropping from a planet’s lower hemisphere. The debris drops continually and forever.

On and on, helplessly, I continued to listen:

“The debris-fall is illuminated for hundreds of thousands of miles... I’ve heard that stars’ ‘beards’ are the misleading name given in Slantland folklore to those perpetually sunlit streams of dust, pebbles, boulders, sticks, garbage, bodies and dried mud and whatever else, that come loose, not actually from the stars themselves, but from their planets’ undersides. The proper term is Nadiral Light. Kroth must have its own Nadiral Light, visible from Hudgung...”

How knowingly I cringed at the relevance for me... Any object, any object Down Under, the moment it becomes loose, must plummet immediately and forever, as I would do at that point on my road which would be termed too far.

*

Having tossed restlessly against the outcrop of rock which lodged my sleeping-bag, I turned and became wakeful as soon as I felt the rays of morning on the back of my head. Hello, nice old sun, I thought as I propped myself up on one elbow; good of you to peep round the Slope and shine on my face.

Vic slept on, huddled on his ground-sheet. He had wedged himself more firmly than I, being well propped against the flank of his steed. Both decapods’ huge bodies were clawed securely into the tilted turf. Forty-five degrees of Slope! beamed that sympathetic friend, the sun; much too much, don’t you think?

I must abandon the impossible journey.

“Impossible”? Oh no, that was wishful thinking. It was impossible only in the sense of “unacceptable”. Physically, it’s all too possible. The danger that I might actually go through with it was very real. For some extraordinary reason I was going South every day, South and more and yet more South, but what was it all in aid of, what was I doing here at all? Some people might be cut out to accomplish crazy things, maybe. I however was inspired differently right now, to yearn for that warm sufficiency named “home”.

Whether that be my Guthtin home, my Topland home or my Earth home, the address mattered little, it was the quality of the yearning, the hearth-fire of the mind, which had been so ignited by the pleasant sunshine.

The sun of Kroth just then impressed me every bit as much as if I had not known of its physical limitations. That’s to say, the power of its presence was no whit diminished by my intellectual knowledge that it was merely a hot and luminous satellite circling the planet at a distance of only fifteen thousand miles.

In fact the orb’s “pocket” size stooped powerfully at me, to overwhelm my imagination with a commanding whiff, an intimacy that breathed of normality and home. Slant or no, I couldn’t go on: that’s what it meant. Nor should I feel guilty or a failure. I had done well to get as far as I had. Now a change of plan was in order.

The question was: how to arrange it?

A few more minutes passed, during which that Sicily-sized sun, in its parade across the sky, got round to raying Vic’s face.

He awoke, and the first thing he saw was the look on my face. “What’s the matter with you?” he asked.

I was in no state to compose a careful speech. Letting the words come as they would, I said: “That astronomical stuff we talked about. The beards. The stars’ beards. The debris-fall.”

“You seem in a bad way, old lad,” he blinked.

“I want no part of it,” I went on. “I don’t want to go near – I want nothing to do with – the equator and beyond. Not even within a thousand or two or three thousand miles of it, not a step further south will I go; it’s unacceptable; I’m sorry.”

“Oh, I think you’ll manage a few more steps.” Watching me, as I opened my mouth and closed it again, he conceded: “You’re mainly right, though – we can’t go on as we are.” I let go my breath as he sat up with a smile: “From a practical point of view it’s hardly possible to ride much further South.”

“You agree, then, that...”

“I can tell that if we ride much further, if our steeds tilt much more, we’ll be tumbling forward over their heads. Just a bit further, and I think we may find a good place to stop.”

“Fine, fine. I trust you, Uncle.” I let go a sigh of unutterable relief. As for what I had guessed about him long ago – that he was heading south for reasons of his own, and that he was a man who could not be stopped – I wanted to forget it, so I did.

Therefore, as I got onto Ydrad that morning, I felt confident that this was the last day we would have to ride.

Vic’s point, that our mode of descent was becoming impractical, was obviously true. It was extremely uncomfortable as we had to slide forward along the beasts’ necks and collapse against their head-crests, which, in their random movement, were now liable to tilt so far forward that we were in danger of pitching over their heads. It was truly amazing that we had got this far, and I certainly could not envisage our continuance in such a style even for another couple of days. No reasonable person could deny that our mission, as originally conceived, had come to an end.

If reason had ruled us, we ought to have turned round, and begun the long climb back northwards. Yet that possibility was not even mentioned. At most, our discussion merely concerned the location of a place to stop. Uncle, of course, had his reasons, but why the dickens didn’t I announce it was time to return? I had decided for home, hadn’t I?

But then, the trouble was, that stupendous climb – I could hardly face even the thought of it.

Our steeds could have retraced their steps easily (they had done the route before); that wasn’t the problem. It was my imagination that wasn’t up to it. You know what it’s like being in a car that’s struggling to get up a steep hill: you sympathise with the effort the machine is making; you try to push it with your mind, you try to will it on, “Go on, go on.” It would have been like that, only infinitely worse. You would understand if you had ever stood there at forty-five south and felt the world mountain towering behind your back.

Since, therefore, I could not even contemplate the return climb, I must content myself with avoiding the far steeper lands. I must, for the time being, seek “home” here in this part of Slantland.

It was still habitable, down here at forty-five; surely I would find somewhere to live.

During the past few hundred miles of our descent the frequency of channels, bare or shrubby or tree-lined gullies, had continued to increase. Their little streams meandered around the variations in the Slope. Typically we came across twenty or thirty of them in a day. Now, ahead and slightly to our right, the notch of another became visible, and we saw that it was a deeper one than usual.

I suppose that I had better get technical and call it a corrie or cirque rather than a gully, for as we veered round to approach its north end it appeared to widen to reveal an almost perfect, though of course tilted, bowl of territory. If you have seen pictures of the giant radio telescope at Arecibo, try to imagine that structure set into a forty-five degree slope. Then picture forty or so of the characteristic houses of Slantland nestling inside it.

“Another village, after all!” I enthused.

“So I guessed,” remarked Vic. “Notice the tracks.” The grass had been trampled recently, to and from a point at the corrie’s lip. Here we dismounted.

We approached a wooden railing and looked down into the great bowl.

A stream spurted from a point in the rock wall beneath us. I leaned on the railing and watched the dancing cascade. An beauty spot, I thought contentedly.

Then we re-mounted and rode around to the side. We found a zig-zag path of steps which would bring us down properly into the hollow.

That path could only be taken on foot, so, for the last time, we dismounted from Ydrad and Gnarre. The saddlebags that contained all our provisions and gear were too heavy to carry down the steps all in one go; therefore we removed all that stuff from the backs of the decapods and left it lying on the grass by the verge. As for the beasts themselves, we had never tethered them, and we had not the means to do so now, so we just left them, too, trusting them to remain close by.

Then we started down.

*

The path took us first towards a hut on a wooden platform. Out of it popped a boy of about eight dressed in boxer shorts, who curled himself into a ball as he jumped off the platform. He then rolled down-slope till he reached some other houses, where he sprang to his feet and began dancing and shouting.

Vic and I strained to make out the words the boy yelled; they sounded like, “We know what to do! We know what to do!” A woman came out of one of the lower houses and enfolded the boy in her arms, calming him, while other people began to emerge from every house, avid for a sight of us.

We went on down to meet them, and as we approached, an elderly man held out his hand and said, “What is this?”

“A safe-conduct,” answered Vic, smiling as he handed over the parchment signed by Gurrer of Jummudge. “Will it do?”

The man held it up to his nose and said, “Mes enfins! You must have come a long, long way.”

His trace of French accent and his French oath formed an isolated floe of Earth culture which skimmed lightly into my heart, releasing an unexpected flood of yearning for civilized connections and global reach. The fellow knew the distance; therefore he had heard of Jummudge! Almost brought to tears, I choked out: “Ah, you’re in touch.” – and then felt the blood mount to my cheeks.

Vic however shot a glance of approval at me.

“Duncan means,” he explained to the Frenchie in an easy voice, “to express his gladness at the thought of all the community of the Wayline resonating like a plucked string.”

“Bof! A frayed string,” smiled the man, “but a delightful hope.”

Vic insisted, “It’s natural, after what we’ve been through, to need to belong.”

The man lifted his hands, tilted his head and said, “You have reached us at last; that is all that matters. Wanderers, welcome to N’skupur. Rest, while we prepare your home.”

I gaped then as I saw that several young men and women were already erecting a couple of extra cabins, in as smooth an operation as if they had been trained to do nothing else. Delight filled Vic and me as our eyes followed the proud gestures of our host. We were being honoured, appreciated, welcomed. Youngsters ran up the steps to fetch down our belongings, and within an hour Vic and I were unpacking our stuff in our own purpose-built cabins.

It took us all that lazy long day to settle in, and at the end of it I was still only beginning to realize how profoundly tired I was.

That evening, on the area of level ground at the foot of the corrie, five long tables were set around a bonfire which blazed under the stars, and the traditional feast was held in our honour. Introductions were informal; we weren’t pressurized to remember a lot of names, for we were expected to take our time adapting to our new life. The elderly gentleman who had welcomed us was a half-English, half-Franco-African polyglot named Alain Utembel, headman of N’skupur. His deputy, Paulo Cidade, was a Portuguese-speaking singer of melancholy songs who accompanied himself on some sort of home-made lute. He crooned and strummed while a bottle of port went the rounds. I lazily overheard Vic conversing with a matronly lady, a Mrs Thurmond, who related how her family, long ago, had come down here from the North and fetched up against “the Nogobar”.

Through the firelight I saw Vic’s expression stiffen. “Is that a barrier – that Nogobar?”

Mrs Thurmond laughed.

“Not a real barrier,” she soothed. “So you don’t need to look so worried. Nogobar is just our slangy word for the fact – call it one of the facts of life – that this place is as far south as you can comfortably get if you want to lead a decently human life. Beyond, it’s no go; get it?”

It got darker and the singing quickened in tempo. People left the tables and began to dance energetically, whirling each other around the luxuriously level floor. I wasn’t up to it; I went and joined those who were sitting around on cushions and blankets among lanterns that dangled from the bushes. A couple of girls about my own age paid some flattering attention to me, with mild rivalry between them. Befuddled with a sudden overflow of the weariness that had accumulated within me for hundreds of days, I preferred the talkative girl, a rangy lass whose name was Lalagen Anoom, since I liked the way I could just sit back and let her sustain the conversation, while I looked forward to seeing her tomorrow, when maybe I would be in more sociable condition. The other girl, Zima Nesdu, shorter and plumper, was content to sit close and smile at her friend and at me. After a while they both went away, saying “see you later” in a way that reminded me of Earth. My head drooped forward onto my chest.

I awoke to find that the bonfire had dwindled to a smoulder. The party was over. Some villagers were sleeping it off outside, but most had returned to their dwellings. Vic was nowhere to be seen; he must have sought his cabin; I went to seek mine. I pushed the door, went in and flopped on the bed with a sense of utter security.

The events of the next day, up until the evening, deepened my sense of having found a home.

In broad outline, we learned our duties as members of the community of N’skupur. It seemed that a remarkably easy life lay ahead of us. Fertile orchards, and large docile herds of the asymmetric cattle and sheep, meant an abundance of food. We were assured that we could learn various useful skills at our own pace. Alain Utembel presented Vic and me with pairs of platform-shoes specially adapted for this part of the world, with swivel-soles that were wedged to support the wearer upright while either descending or ascending a gradient of forty-five degrees. When you needed to go out of the corrie and walk across the Slope you simply turned the soles to right-angled position, one way or the other way, depending on whether you were going east-west or west-east. This was the way to get around. We let ourselves be shown round the local pastures and orchards, and we picnicked at noonday a few miles from N’skupur.

We were back in the village for supper, and then we were promised an evening show. Utembel explained that this would consist of a variety performance of songs, sketches and one-act plays based on the folk-tales of Slantland.

It all sounded pleasant and harmless, and I awaited the event in a state of floppy happiness, secure as a kitten carried in the jaws of its mother.

*

In the southernmost, low-gradient region of the hollow, where you could almost pretend you were on the floor of some kind of dell or dingle on Earth, a stream had been diverted into a separate channel. Its flow, therefore, took it through the village on a course that was wide of dry former watercourse. This had made it possible for the former stream-bed to be levelled, and its space enlarged to fit about fifty or sixty seats, in three crescent rows, facing a stage.

Vic and I were having a mild argument as we strolled in the company of other groups converging on the open-air auditorium. He had just remarked to me that he hoped we would meet all these interesting people again “on our way back”.

“On our way back? From where?”

Vic laughed and clapped me on the back. “Don’t worry about it,” he said.

I stopped and faced him. “Are you planning something? I worry, you know, about what you’re up to. We’re not about to go any further south now, are we? We’ve just made this our home. This is the end of the line.”

He cupped a hand on my elbow. “Mute that tone of surprise, will you? Come on, let’s get seats for the show. Stop fretting! My only plan, if you can call it that, is, that if you insist on staying here, I’ll end up by going ahead on my own. Hey,” he interrupted himself, “that’s interesting – look at that.”

I followed his gaze to where seats were being taken.

In every case the person who sat directly on a seat was a man. The women, instead of taking places of their own, were plonking themselves down onto the laps of the men. I, accustomed to the more dignified ways of Upland folk, raised my eyebrows at this. I raised them even higher when I noticed that the wives weren’t, as a rule, sitting on the laps of their husbands (I had become acquainted with enough of them to be reasonably certain of this).

I muttered, “What is this – a wife-swapping party?”

“I doubt it,” Vic chuckled; “not in the full sense, anyhow. Still, you might remember the Romans’ invitation to the Sabines.”

“Uh?”

“Except that here it’ll be husband-hunting instead of wife-snatching that’ll be the climax of the show. Excuse me, I think I see a lady waiting for me...” – and to my utter astonishment he marched brazenly over to where Mrs Thurmond was standing by a chair. Vic sat down and the lady promptly sat down on him, put her arms around his neck and began to converse as though this were the most normal way to behave.

Well, at least I needn’t wonder any longer why there didn’t seem to be enough seats for everyone in the village. Only half as many were required! I ambled forward, seeking a place for myself. Three quarters of them were now occupied. The audience was dignified enough in its way; its spirit good-humoured but not promiscuous, and I silently repented my remark about wife-swapping. On the contrary, the procedure seemed to demonstrate how confident they all were in their integrity. And yet, I wished I had Vic’s coolness. Which was going to stress me more – to be sat on or not to be sat on?

I took a place, and tried to keep my eyes on the stage.

In my thoughts a certainty took shape. This evening will determine the rest of my life. But before I could question it, or wonder whether it was a warning or the result of rapid subconscious calculation, I saw, out of the corner of my eye, the outline of a well-built girl edge over from my right. Then there were no more ifs or buts. Plonk! My lap was full. My arms went round a pullover and its cuddly contents.

I couldn’t see her properly as her face was turned to the stage. Naturally. Nothing personal. Custom, no more. Nevertheless the sudden honour, of having been selected, blanked out all other facts. I was aware that the variety show had begun but I paid it no attention; I swam instead in a sparkling ocean of amazed gratitude as I tightened my arms around the girl, while not one single mutter came from that spoil-sport area in my skull, the Department of Keeping Things in Proportion. I thought: “The greatest compliment of my life had just been paid me.” The girl moved her head as she felt the pressure of my arms. Her left cheek became the next target of my magnetized will: it suddenly seemed a crime not to kiss that cheek. My lips performed the deed.

“Well done at last, Duncan,” she said quietly.

Emboldened, I kissed her again, and rocked her as I spoke her name, “Zima.” Zima Nesdu, the stocky girl who had been mostly silent while her garrulous friend chatted to me the previous evening. It would have been disgraceful not to remember her name.

She whispered, “It was about time you did that.”

So – in this case it was more than custom, after all. Her presence on my lap did not stem just from the quaint social habits of the N’skupurans. Doubtless most of the other pairings were merely sociable, but –

I heard a cheer from the audience around me and shouts of “Encore!” Perhaps it was time I paid some attention to the show. I most definitely did not want to seem rude to anyone on this special evening.

A chorus chanted the encore:

Fear not that you are close to Udrem here;

Think how you’ve slid from Neydio down;

The final slide would be thrice as far.

I whispered, “Zima, tell me what this is about.”

I loved her for her immediate grant of my request as she whispered back, “It’s our little play about the founding of N’skupur.”

The play’s dialogue wasn’t brilliant, and the characters were rather wooden, but slowly the message got through to me.

Centred on the day that the founders made up their minds, it dramatized the historic moment when old Jacob Stoombalaf, the pioneer chief, pronounced: “This is liveable!” – and his words were echoed, then as now, by a cheer. I cheered, too, but also I sagged as the truth leaned its weight on me: the decision merely to stay was portrayed as the ultimate in daring: that was the message of the play; the entire debate had been about whether to stay or to go back; no one, at any time, had considered going on to be an option. In fact no mention was made of the lands further South except, “Fear not that you be close to Udrem here…” To have gone on down further would have been utter madness. Of course. And the horrors of the South didn’t matter to me, since I was making my home here – only, in that case, “here” had better be enough.

Zima’s warm torso in my arms distracted me once more, and my eyes veered from the stage as the sketch about the pioneers drew to its end. I rested my head against the girl’s shoulder. Paulo Cidade had begun to wail one of his songs; Zima swayed with the rhythm, and I swayed too, but it became a cover for a secret trembling. I squeezed my eyes shut like a man with a migraine. Question: do I succumb to this girl’s spell? Zima’s no Elaine Dering. She isn’t even an Elaine Swinton. But – face it – those two are gone from my life. Gone, never to return, whereas this girl is here, now, and besides, it’s problematic to think of one girl being ‘more’ attractive than another: a girl is either attractive or she isn’t, and if she is – if she has that mysterious whatever-it-is – well then, she’s infinitely so. Therefore to possess any such infinity is enough to make me rich in romance even if, given the choice, I should have preferred a different infinity, namely, Elaine Dering. And why must I sort all this out now? Because at any moment she may turn her head and look me in the eyes. At this moment I can only see about a quarter of her face, yet before much more time has passed she is sure to turn around, and when that happens it won’t just be eye-looks-into-eye, it’ll be two continental plates of emotion colliding and up-thrusting to form the continental divide, after which all my future moments shall trickle down to a settled home life here, with her, unless I am stopped before the divide by some great event which pushes me the other way...

Absolutely nothing could I do about it but sit and wait for the future, pleasant or not, to clobber me. Whichever it was, it was terrifyingly inevitable unless something to prevent it happened very soon. Oh if only my head could cease its chatter. Oh the longing for action, urgent as fresh fish in the post, useless if delayed. It was appalling to think that without a decisive change in the course of events within minutes of now, I would be here for the rest of my life, the “homebody” part of me would have won, and the adventurous me would be dead...

Hang on, though, wasn’t that just what I had wanted, exactly why I had stopped here? I wanted a home; I wanted stability. And when I was offered exactly that, the idea appalled me; so, evidently, I was nuts.

I wouldn’t worry, mate, said the voice of self-knowledge from down deep. It’s all been taken care of. As usual.

As usual? With regard to free will, was I getting as cynical as Vic?

Now then, what was this? Something had happened. Cidade’s song – it had come to an end; the crooner had broken off abruptly.

Next thing I knew, Zima had slid off my lap. She was gazing over my shoulder, and everyone else, likewise, was getting up and turning to face the south entrance of the corrie.

*

No less excited than everyone else, I was more hesitant because I felt the stakes were higher for me than for any other person in N’Skupur. At first, indeed, I hardly dared to move, and could not bear to look up. My downcast gaze slid along the ground cautiously southwards, until my field of view came to include the whitish limbs, and then the bellies, of two tall creatures on the threshold of the village.

Decapods – but not ours. Nor our enemies’, either. Human riders’ legs hung either side; legs that ended in two pairs of made-in-Topland boots.

The sight yanked Fortune’s wheel, swerving the course of my life back onto an older road and a larger happiness. I did not dart forward to greet the arrivals, though I knew them by name; I advanced sedately, while the handsome couple dismounted to introduce themselves to us all.

It goes to show how isolated I must have become after a mere seven weeks of the journey down the curve of the world with its steepening that crunches the soul – that the appearance of Cora and Rida, whom I had known against the background of a decently level horizon, affected me so profoundly. It was because I had known them in Topland and only in Topland, that the sight of them evoked so powerfully the breath and touch of the civilization I had forsaken. I almost hero-worshipped them in that moment.

Cora had never exactly been my girlfriend in the romantic sense, though at times I had felt we might drift in that direction; we had quarrelled for what you might call cultural or political reasons, not that any of that mattered now. As a beautiful and intelligent Anglo-Greek slightly older than I, she seemed the ideal partner to Rida Sholkov. He, a swarthily handsome Russo-Egyptian, tall, lean and dignified with his pencil-thin black beard, was (my memories suggested) more highly educated and widely travelled than she; his field was astronomy but geology field-trips had been a sideline. Now he looked more than ever the athletic, healthy-mind-in-healthy-body scientist. On the other hand he had lacked the sharp set of Earthly recollections which Cora (and I) possessed. But the important thing was, they were both out-doors type intellectuals, ideal explorers. And they had already seemed attracted to each other when I last saw them. Now as they moved side by side among the welcoming folk of N’Skupur, they were obviously a couple favoured by fortune, who faced with gladness their mission in life together. The government had sent them, of that I was sure, and in doing so had picked an efficient and compatible team. I stood taller, reminded of my own official status.

Cora was shaking hands with Utembel as I drew closer, and I heard her say: “We surely are glad to find you people. Whew! I tell you, we could not have ridden another step.”

“In fact,” put in Rida, “that’s off the agenda now, would you not agree, mister headman?”

“What is off the agenda? Oh, riding! Absolutely, Mr Sholkov! When you have lived here a while, you’ll be used to getting around on foot. We have special shoes for use on the Slope and we’ll be happy to let you have some pairs each.”

“We’ll gladly accept your hospitality this night,” said Cora.

Utembel pulled a woeful face. “Longer than that, I hope!”

“No, sorry, tomorrow we shall have to be getting on.”

“Bof! You won’t find a better home anywhere on this latitude, I’ll wager! Neither east nor west from here...”

“We’ll be pushing on south,” insisted Rida, curtly. At that moment he saw me. His eyes sharpened. “I know you, don’t I?”

I stood up straighter and put out my hand. “Duncan Wemyss. We were on the hike in the Mulkut Hills...”

Cora screamed, “Duncan!” and swept me into a hug. Rida grinned and shook my hand. Events were booming like a gold rush. I introduced Vic – they knew him too, slightly. Cora announced radiantly to the throng, “Hey, people, I can hardly believe this – but I’ve run into folks I knew up in Topland! I always say, you’re bound to strike lucky if you keep to the Wayline!” All of the assembled N’Skupurans reacted in good humour to the reunion of old friends, except for Utembel, who, after Rida’s we’re pushing on South, stared aghast for a second or two, then took a breath that wiped the dismay from his features but left a disbelieving smile.

*

Flames flickered low, nine-tenths of the celebrants had left for bed, while my companions and I continued to lounge around the campfire tirelessly swapping stories. A few N’Skupurans also remained to throw glances in our direction, but I, re-born as an adventurer, stuck to the company of my friends and to one datum of vital importance: Cora and Rida were determined to continue southwards, no matter what anyone might say or do. As for Vic, he, as I already knew, shared that aim and would react ruthlessly if anyone tried to stop him. So then, what about me? Could I allow myself to be left behind? Not for anything. From whatever quarter pressure might come, I was not going to let its jaws fasten on me.

Cora talked of the origin and purpose of their mission. “Roving commissions for the ‘Roving Wave’,” she explained, telling us of riders who had followed my example and Vic’s in mastering the control of captured decapods after the Battle of Neydio. “Rida and I have undertaken to get as far south as we can. If possible we are to bring back a report from the Gonomong heartland. Do you think we’re crazy?” She turned to me as she said this.

“Not a bit.”

“It’ll take a chunk out of our life.”

“Well, so what?” I encouraged. “The Beagle took years out of Darwin’s life, didn’t it?”

“And no regrets, I dare say – I like your choice of comparison very much. Eh, Rida?”

He said, “Ah. Darwin. Yes, the relevance is clear. He ‘sacrificed’ years of his life on a voyage of discovery, eventually world-changing, and it made his name.”

“Just as anyone,” I rubbed it in, “who can be the first to get back from Udrem to Upland with solid data under his or her belt, will be set up for life.”

Cora smiled broadly. “You say the right things, that’s what I like about you, Duncan.”

“But you don’t need me to say ’em.”

“But it’s nice that you agree.”

It would be even nicer, thought I, if Vic and I were as ready for swift departure as she and Rida were. They had their beasts loaded and within reach, and they could, if necessary, scoot fast. We weren’t in such a fortunate position. Ydrad and Gnarre were not in view, having been left to graze outside N’Skupur. If we were to try to pack up, it would be impossible for our fetching and carrying not to be noticed, impossible for our intentions to be concealed... yet even as I chewed these thoughts I became aware that Vic had left our circle, that he was passing to and fro, stealthily in the dimness... My pulse quickened as I understood: he was putting all my stuff, and his, onto the mounts belonging to Cora and Rida. He eventually came over to whisper the plan.

We would not sneak away without saying goodbye to our hosts; that would be too mean. But we would improve our position first: get just a short way outside N’Skupur while it was dark, wait to be spotted at dawn, and say our farewells on the open Slope.

We never did sleep that night.

The exit manoeuvre went without a hitch: by the time the sun peeped round the curve of the world we were sitting on the lower lip of the corrie, putting on the special wedge-soled shoes designed and provided by our hosts (Vic and I donated our spare pair to Cora and Rida). Thus shod, the four of us stood, Cora and Rida experimentally, Vic and I more easily, in position just one step down-Slope, on a rather dessicated, crackly-leaved surface. Though I had tried the shoes before, it was a queasy moment for me. I knew that the strange N’Skupuran footwear did at least grip, but as I looked to the future I had to admit that it wasn’t going to spare me the wear and tear on muscle and bone, clump-clump-clump down a tilt which was already the angle of a tiled roof and could only get worse. And there was no other way to do it: we must tackle the Slope on foot from now on. That was what I aimed to do, but still with inconsistent longing I turned my head and glanced back into the corrie.

Rida’s dry voice sounded in our ears, telling us he thought it best that we recede a bit further, about fifty yards down from the entrance to the village. We agreed, and like toddlers who depend for balance upon the hand of an adult, we clutched our four beasts’ side-straps (Ydrad and Gnarre had been led round by Vic to join the other two) and “took the plunge”, crunching gingerly, step by step, downwards, southwards. Thank goodness, the decapods responded intelligently, at a mere shuffle compared to their usual gait. Though we couldn’t ride them on a slope this steep, we needed them as much as ever for portage, and more than ever for support.

When we had covered that short space which Rida had recommended, we halted and silently busied ourselves to re-distribute the decapods’ loads, I dare say all of us wondering, as I did, how the krunk we were going to accomplish this crazy journey. One thing which absolutely had to work, had worked: the decapods acted as our moving props; thus we were deprived of the best excuse for retreat.

Ah, we were spotted! A villager appeared on the lower lip of the corrie, saw us and darted back; a couple of minutes later a crowd of them filed onto the ledge. We craned our necks at them; they peered down at us. Our position was dreadfully simple. The people of N’Skupur, whose invitation we had spurned, only had to stand there, on the Slope that soared beyond them to the limit of vision: no threats, no kicked stones or rolled weights were needed to tell us, that when you make a choice, inside you a pointer swings, showing you what you’re going to miss forever and ever. You can write it as an equation:

Eating your cake = not having it any more.

Then the figures moved, their demeanour most casual, descending towards us in mild scorn. As they came amongst us I heard Utembel saying to Vic, “Since you’re determined to go, we’ll share with you what knowledge we have...” and they began to discuss the route.

My own particular “cake”, Zima Nesdu, loitered with her hands in the pockets of her

grey slacks – an extremely confident pose to sustain on a forty-five degree Slope. Her impersonal glance swept over me. I lowered my eyes and said to myself, “Well, to break free was what I wanted, wasn’t it? Didn’t want a fuss, did I?” Pointless to apologize, pointless to explain, pointless to howl in regret. Then as Zima circulated closer my neck swivelled to avoid the sight of her and my glance lit upon another girl, Zima’s friend Lalagen Anoom, taller, looser-limbed, tow-headed. This one wasn’t in aloof mode. She was scowling straight at me and challenging me, merely by her existence, to step towards her.

I answered before she even spoke:

“Zima seems not to mind.” It sounded weak in my own ears even as I said it.

Her brows went up:

“She does not mind; but how were you to know that?”

I felt hot, and wished I were elsewhere.

“I didn’t know, it’s simply that now I see it’s true.”

“But for all you knew, you might have broken her heart.”

“I admit...”

“You did not dare tell her you had decided to leave.”

“I did not dare,” I agreed, flatly.

It actually felt good to be accused by that glint in her eyes, sharp but fair and with the brains and honesty behind it to guarantee a hearing.

“And if you think about it,” I played my card, “the fact that I did not dare to say goodbye to her is the greatest compliment I can pay, to her power.”

Lalagen, with a grudging nod, reached down to where a heavily packed grip was lying at her feet, picked it up and parted from me, wending her way, I noticed, towards the spot where Utembel and Uncle Vic were in conference. I couldn’t guess what they were saying and I didn’t care. My former doubts of our ability to break free from N’Skupur had vanished into the blue infinity that shoved its face into ours and could not be thwarted. I mopped my face and thought, soon, very soon we will be out of this.

The marvellous moment came. My companions and I took hold of the side-straps of our decapods – no longer steeds, now mere beasts of burden and support, a combination of giant packhorse and crutch – and we were at last properly on our way. Our recent hosts, in exasperated respect, called out their good wishes, and waved farewell; after a minute I looked back and saw them watching us recede down-Slope; after another minute I looked again and saw that they had turned their backs and were plodding up to their village.

This was true of all except for one of them.

One who had obtained permission to come with us. Our group now numbered five.

Two of us held onto Ydrad. I clutched the front left strap, and the newcomer held the left rear strap, someway behind and above my back. The result of this was that she could look at me whereas I could not look at her unless I made an effort to turn.

I asked, “What did you say your real name was, Lalagen?”

“Anything but Lalagen,” answered the voice up-Slope behind me.

“We need to settle on something,” Vic called out, somewhere to our right, hanging onto Gnarre.

“For now,” said the girl, “I’ll choose to be called Heather Cranfield.”

I said, “Very well, Heather – but why that, in particular?”

“I just fancy the name. I like the way it has no connection with my life so far, no link with anyone I know.”

I let the subject drop. No hurry at all in getting to know the girl. More important just then was to get back into the swing of the descent; I had to concentrate to make sure that I did not trip on the exposed roots of the shovelgrass, which provided useful but tricky footholds.

For long hours we remained almost completely silent, diagonally sandwiched between dominating sky and dizzy Slope. An ant crawling down Mount Fuji might have felt as we did, except that no matter how long we journeyed there would be no levelling off to look forward to, no flat ground at the end of our journey. Quite the contrary: the gradient must increase, eventually to vertical. Madness to continue, and yet we continued. Periodically, as usual, I asked myself why. A reason must exist. Every action is performed for a reason. Well then, for starters, how about our official aim? Target: our enemies the Gonomong. They must live somewhere in the very far south. Honour and glory must accrue to the first expedition to bring back solid data regarding the Gonomong heartland... Honour and glory. More than when Zima had chosen to sit in my lap. Or so I supposed.

At any rate I had demonstrated a certain independence of mind. Hadn’t I? Leaving the girl behind. Decisiveness. Freedom of the will. Look at me now, travelling on down. Always it ends with me travelling on down. That’s how my freedom of the will always ends. Not in the likes of N’Skupur, strong though the jaws of romance may be. Not the steeliest of traps can keep me from my descent towards Udrem. I can entertain myself with what plans I like, up to the point of decision, and then I must use my independence of mind – to choose to go onward.

As in: “We’ll give him a fair trial – and then we’ll hang him.”

I wished I had a can of spray against these buzzing thoughts.