kroth: the drop

3: the master of fear

“Still moping over that girl, Dunc?”

Cora and I were resting on a ledge. Or you could call it a step. Or (my mind briefly coddled the idea) it could have been the north face of a hillock if the Slope had been tilted back to level...

A quaint, fleeting thought. And futile. Horizontality was long lost to me. So very long lost, that the savage gradient on which I now lived was felt in my bones to be absolutely normal.

In that sense The Slant made me, too, as savage as the slope.

“Yep,” came another verbal prod from Cora, “looks to me like a definite case of mope.”

She was cross-legged. I was propped up on one elbow, like an ancient Roman at dinner. My other arm, shoulder and knees were aching from strap-hanging strain, as each day I had to hold onto Ydrad’s harness for hours during our descent. No matter what mental adjustments one might successfully make, the physical problems of the Slope remained.

“No reaction, Mopey?”

Bemused at her attempt to needle me, but not actually annoyed or worried, I reflected that it was a few days since I had spoken to Cora, a whole day since I had even set eyes on her, and I could not expect to be up to date on all the moods of my companions. Our little group no longer maintained tight formation. We no longer felt threatened by our foes. By this time the Gonomong horde had surely gone down so far ahead of us that we must be following them at a completely safe distance. Nowadays therefore we rambled and allowed ourselves often to become separated from one another by the countless ridges that stippled these latitudes of Kroth. Discipline was lacking; we had no overall leader. We were no longer a united expedition but rather two expeditions running parallel, which was not a problem as our five personalities got on well together, most of the time.

“You got girl trouble, Dunc,” persisted Cora, and I finally decided that my silence wasn’t going to make her give up. Might as well reply – might as well give her the reaction she wanted. It was actually not a bad moment for a confession. My other three companions were out of earshot, and if Cora must work her way through an agony-aunt phase, now was as good a time as any...

“‘Girl’ is a bit vague,” I said in a tone of bleary puzzlement. “Whom d’you mean exactly?”

“Whom do you think? Heather, of course.”

“Now just a minute…” – a pinch of indignation, to season the dialogue. “How the heck – and what the heck – do you know about it?”

“Nothing much, only I can tell a moper when I see one.”

“Yeah, well,” I muttered, going off on a new tack, as it suddenly occurred to me to face facts, “I suppose I probably have seemed rather – er – pensive lately... thinking about...” (I paused) “Zima Nesdu.”

Ha! That surprised Cora. She looked quite put out for a moment. Her theory was in danger – her theory that I had been moping about Heather Cranfield.

“Eh? And who pray is Zima Nesdu?”

“Someone I met back in N’Skupur.”

“Well then – come on! You won’t see her again.”

“I know.”

“So forget the bird in the bush and concentrate on the bird in the hand.”

“Yes but you see, Cora, the – er – bird in the bush packed more of a punch.”

“But why, for goodness’ sake? Since it’s obviously Heather you ought to be concerned about.”

I then told the story, and I found it a struggle to tell. “Heather no doubt still thinks I treated her friend badly,” I finished, “yet I myself feel...” I was going to say hurt, but I bit back the word, lest it invite a scornful laugh. “It’s the conjuring trick Zima played on me, that really got me,” I burst out, to my own astonishment. “I mean – boom! Warmth all gone in a flash! And then lo and behold: indifference. What else can I call it – emotional conjuring, that’s what I call it...”

“But you wanted out.”

It was absolutely true. I had been determined to continue my journey, to leave Zima behind in N’Skupur.

“Yeah, but I did believe in her. I thought she really, er –”

“Quite right, I dare say. It was real while it existed.”

“Cora, you know what, you’re an Authority, you are.”

The jibe had no effect. “It’s obvious that it couldn’t have lasted. So – would you rather have had a big tragic scene or something? Far better just to switch off, surely. You can call it a ‘conjuring trick’ if you like, but to me it seems like common sense.”

“Oh, yes, I admit that.” I smiled.

She asked, “What’s so funny?”

“The change in you, Cora.”

“Everyone changes.”

“The extent of the change, though. Where’s the tough-minded, political Cora whom I knew in Topland, who would never have considered it worth her while to probe into my (imaginary) love-life?”

“Sorry. I’ll mind my own business, if you like.”

I shook my head. “You don’t have to do that. I’m quite flattered by your interest. Besides, it’s natural you should seek, er, new material for your, um, agony-aunt side –” (she trilled with laughter) “which is undergoing a natural expansion since your own love-life is going so well at the moment.”

“Brilliant,” she smiled. “Fantastic little speech. Totally eclipsed whatever it was that I was going to say.”

“Well then, if you like, I’ll tell you something,” I said, “about how I’m getting on with Heather. On that topic, here’s my thought for the day: for a romance to work, love is not enough...”

“Now who’s sounding like an Authority?”

I ploughed on, “As well as love one must also have belief. And my belief in Heather is... um... zero.”

“Eh?” she said, incredulous.

“Absolute zero.”

That stopped her.

I reached over, patted her arm and added, “Fret not, Cora; I do appreciate your interest. Think what a lonely world it would be, if everyone did mind their own business.”

She let it rest there, and I thought, gratefully, how good it was, on a journey like ours, to be at one with the way things are, so that our southward descent was ultimately no different from the constant trickle of water down the flank of the world. Good girl, Cora: she makes her observations, and I make my observations, and there’s an end of it. You don’t question the flow. What a waste of time it would be, to analyse my judgement of Heather Cranfield.

That world-wide trickle of groundwater came to mind again, and, just for a moment, my nostrils twitched.

Could it be that I had fleetingly sensed the smells which (logic says) must accumulate the more one goes down southward, as all the sewage from man and beast on Kroth sinks in that direction?

Ah yes, true – but only if you think about it. You’d make a fool of yourself if you forgot the equally constant flow of adaptation. The increments are slow, the journey gradual, too gradual for the smell to be noticed –

And a smell that is not noticed is not a smell.

Some days later, when the girls happened to be lagging some distance behind, Rida and Vic and I were first to reach a landmark, a colossal, isolated kapok tree, where the five of us had agreed to gather for lunch.

The giant tree grew on a bumpy projection of ground, a random interruption in the Slope. I sat myself down with my back to the trunk and soaked in quietness as I often did, to admire the heavy blankness around me, the oceanic Slope and sky, the magnitudes which cushion the soul. But then as soon as I opened my canteen to take a swig, I was reminded that not all the complications of life had shrunk out of sight. I hesitated and wrinkled my nose – again.

Rida solemnly asked, “What is the matter? Does it pong?”

“Imagination only,” I smiled. “It doesn’t do to think too much.”

Vic plonked himself down and opened his own canteen. “You’re right there.” He took a

gulp. “Doesn’t do to think about how many sheep, et cetera, have peed in the streams between here and up where we started.”

“But you have been thinking,” I pointed out.

“Don’t want to over-do it, though. Don’t want to get like the kind of smarty who goes on about how the people of the Middle Ages must have smelled because they never took baths. As if you’d ever notice, if you’d lived then! A smell that isn’t noticed isn’t a smell.”

“That’s just what I told myself.”

Vic tilted his head back and swigged again; I briefly wondered if we were all going to die of typhoid before we had a chance to die in Udrem.

But then I switched back to big thoughts. The giant tree at my back: how deep its roots must go: I likewise should drink and not be bothered. My critical faculty was a waste of time. Peace reigned in my head.

The girls arrived. Lunch proceeded. I quietly enjoyed the food and the conversation. My eyes roved lazily. What was Heather up to, busying herself with a saddlebag? I saw her look over her shoulder with a kind of shy hope in her face which mildly roused my curiosity.

She was coming towards us, her arms full of flappy stuff, fabrics of some kind. Her expression was set and serious. She took us all by surprise as she presented her gifts.

Oblique royal-blue sash-bands, plentifully lined with useful little clips, pockets and a pouch expandable to knapsack size, they were to be worn over the right shoulder and under the left arm. She put one on herself and said:

“My people know from experience that the tribes respect these.”

“Tribes?” asked Cora.

“What I say applies to any of the savages of the far south,” Heather explained. “We won’t be attacked, we’ll be taboo, if we wear these bandoleers.”

“Why?” asked Rida.

“Because they will think we come from Topland. In fact, all of us except myself do come from Topland, but it’s also important that the savages recognize this, because Topland is holy to all of them, too holy to touch, and that’s what we want; we want them not to touch us.”

Vic snorted. “Topland holy?”

“Enough, it seems,” said Heather limpidly. “Of course,” she added with a vague shrug, “when I say the tribes think this or that, I admit that somewhere there are bound to be exceptions...”

“No, don’t let’s talk about exceptions,” said Vic. “My head’s spinning as it is. We thank you, Heather, for your no-doubt valuable gift. But just tell us why you are handing the stuff out now. Why not at the start?”

Heather looked demure as she said, “At the start I was not sure how serious you all were, but now that I know you better, I know you will never stop.”

The conversation faded from my ears: whimsically diverted by that simple word stop, my attention wandered to a memory which swam up from my Earthly life, a phrase, a book’s title, How To Stop Worrying. I had heard mention of it but I had never actually seen that book, and now I reflected that I would never have the need. I had found out for myself how to deaden the worry-nerve.

Nerves, though, exist for a reason. Better not get too calm.

My thoughts then zipped to the description of leprosy in the Thomas Covenant saga by Stephen Donaldson, in which the hero had to be careful, very careful, to inspect his body regularly for damage because his nerve-endings had been destroyed by the disease and so the warning system of pain had been switched off...

In my case, for “pain” read “fear”, and for “leprosy” read “The Slant”.

Not for the first time, I wondered if there might be cause for concern at my lost capacity for fear.

I reviewed the past few days and decided, with an inner smile, that the answer, at present, was no. My courage was passive only; it enabled me to endure, and that was all; any possibility that I might develop into a daredevil was quite remote.

*

How to plod long treks: you partly “switch off”, you make use of the autopilot facility which exists in us all. But it’s not an empty thing; you really live that length of time, though your awareness does rather skid. While physically the variegated plonk of your boots is anything but smooth, mentally your consciousness can slide down the world as though it were a bannister.

One effect of this is the way conversations seem to run into one another. So, we were talking about “allies” one day, and Uncle Vic mentioned the idea that we might find a powerful friendly ruler in the hinterland of our foes, someone like the medieval legend of Prester John; in fact this was the continuation of another talk the day before, and it’s almost as if the two were the same, one nigh word-for-word a repetition of the other.

Both conversations were based on wishful thinking. This became apparent when, the very next day, we had our first contact with a native tribe of this region of Slantland.

We saw, first, a column of smoke to our right, and then a score of figures outlined against a patch of woodland. Through our binoculars we made out that they were people clad in woven grasses and skins, squatting round the remains of a fire.

One of them saw us, and stood up. Seconds later the rest of them rose likewise, while we continued to descend past the group at a distance of a couple of hundred yards. Not a sound or a further move did they make while we remained in sight. Evidently our bandoleers were having the effect intended. We were going to be left alone, as long as we wore them. Down through all the lands we passed, we would be ignored, until we reached our real foes, the Gonomong...

“This is so easy,” I remarked, “it’s almost boring.”

“Yes,” agreed Vic, equally flippant, “contact by eye only; so it looks as though we won’t get to find any Prester Johns, nor shall we need them.”

I heard a sharp intake of breath. I looked around but it was only Heather, her expression tense. I guessed she might not like our words that had seemed to ‘tempt fate’, so I added, placatingly, “Sorry – shouldn’t count one’s chickens, I know.”

She made no reply.

Days came and went, and we descended past several further native encampments within sight of the Wayline. The occasions blend and fuse in my memory. I am left with an image of bluish silhouettes in an oblique, static line, as if I were going down one escalator past another which was motionless and thronged with figures cut out of flat shadow. Those tribes must have been disciplined. Even their smallest children were quiet as we went past them. If it had not been for Heather’s explanation about the bandoleers and their religious significance, I should have assumed that it must be the sight of our decapods that awed the natives. After all, in their place I dare say I myself should have been struck dumb at seeing the magnified inchworms humping down-Slope with human figures dangling at their sides.

“Lots of questions we won’t ever answer,” remarked Vic after one of these encounters.

Cora said, “Like, for instance –?”

“Oh – academic questions, I mean. Speculative anthropology. The Updrift and Downdrift schools of thought – heard of them?”

“I have,” interjected Rida, crisply. “Academic arguments, as you say.”

“Academic guesswork,” amended Vic, “by people who have never been down here and who speculate through their hats, as they ask: Must the drift of power, among Slantland tribes, be downwards, or upwards? Does success propel you North, or South? You can argue either way. If you climb the Slope so as to get above your enemies, so as to roll rocks on them, the avalanche you start won’t stop but will roll onto your own people unless you get them all up higher, so that’s an incentive for wholesale migration upwards, for permanent advantage. On the other hand, attack is much easier downward. Therefore aggressors will find themselves drawn down and down as they loot and displace their victims, so you have good reason to argue for the priority of a downward drift. If you’re writing a thesis, you ‘pays yer money and takes yer choice’ between the U-D and D-D, updrift and downdrift views. Pity we can’t settle the question. We’ve reached the right place, but the contacts are lacking.”

“Never mind,” said Rida. “Hard science is a better bet.”

For some reason I glanced at Heather just then and again I saw that tension, that frustration amounting almost to fury, on her face. Well, poor girl, doubtless she wished she’d had a college education, but she ought not to feel inferior to the rest of us –

One day, as she strap-hung behind me, I heard her say:

“Now you talk, Duncan Wemyss.”

Her voice was still cool when directed at me. From this I concluded that she still had not forgiven me for the way I had ‘jilted’ her friend, Zima Nesdu.

“Talk? What about?”

“You’ve got a live memory of the Earth-dream, haven’t you?”

“Yes, and so have Vic and Cora.”

“I want to hear about it from you.”

I turned to glance back and up at her. “Why? Why from me?”

With an irritated wobble of her head, she ground out: “Never mind. Talk.”

Bewildered by her mood, I faced back down-Slope. It came to me, strongly, that I really didn’t want to talk about my past. “It’s getting a bit hard,” I evaded, “to think of something new to say about Earth.”

“Rot,” she replied. “Bilge.” So primly did she utter those words, I almost laughed, though it would have been an affectionate laugh. Vulnerably earnest, our Heather. Mustn’t forget, I reminded myself, that she’d been fantastically courageous to leave her home and trust herself to our mad expedition for no other reason than a yearning for a ‘wider life’.

I might, I thought, have to indulge her... but before I could think of what to say, her voice broke upon me again.

“You almost sound as if you’re ashamed of Earth.”

“Bull’s-eye,” I snapped.

“What?” she demanded.

So – she didn’t know what a bull’s-eye was.

I self-consciously glanced to my left where, about eight or ten yards away, silhouetted against the great diagonal of ground against sky, Cora and Rida were strap-hanging from their loyal, down-creeping beasts. And somewhere close to my right, I knew, Vic likewise hopped and plonked downward with the support of Gnarre. We were all sticking closer together now, for we had begun to enter a land inhabited by folk who were wilder-looking than the ones before: tribesmen who carried spears – though they all continued to stand silent as we went by.

Under these more “cramped” conditions, if I were to get talking to Heather about my past life, with my other companions close enough that they could not but overhear, I sensed that things might get embarrassing. For my identity still stemmed from Earth, and with regard to Earth there was an aspect of my own character which I wanted to hide.

Let me whisper it to the reader:

I call a spade a spade. I call yuk, yuk.

“What’s the matter,” I heard her say, “don’t you want to talk about your murky past?”

“No,” I said coldly.

“Sorry,” she said, “I’m only joking.”

“I’m not,” I said. I knew that I would be incapable, once the subject came to the fore, of concealing the most obvious truth about the culture I had grown up in.

Nor would it be possible, without unceasing self-censorship, to conceal my joy at having escaped the yuk – and if I failed to conceal that joy, Heather would catch a revealing glimpse of my inner fierceness – my loyalty, my priggishness, call it what you will. And the others, too, if they were in earshot...

Blow it, I thought. I can simply go on strike.

I allowed the silence to drag.

Heather broke it:

“Really, Duncan, you don’t have to talk about Earth; I was actually just trying to get the talk round to the subject of you.”

“Oh? Er...”

“About why you take so little notice of other people.”

“Hey, that’s not fair; I listen, I always listen, I give my full attention, when anybody speaks...”

“Little real notice,” she insisted, firmly.

I changed tack... for, when I thought about it, I knew what she meant. She was telling me that to listen was not enough; that to ‘take notice’ meant also to respond, and that I had not done so, at any rate not sufficiently. Time to formulate an excuse.

“The fantastic nature of what we are doing,” I suggested, “lifts us all, don’t you think, a bit beyond the personal? So we descend quietly. By and large we think big; we forget our little selves.”

“Shouldn’t it sometimes work the other way? Why doesn’t the greatness of what we’re caught up in make us huddle together all the more, seeking human comfort, so that we talk to each other and understand each other?”

The silence all around me grew thick. It was a fog of silence in which D. Wemyss’ cleverness lost its way. Heather had posed a fair question. My thoughts had lost their traction; they spun like wheels in mud.

Vic meanwhile approached us from behind, and at this point he and Gnarre became visible on our left side, no longer hidden from Heather and me by the bulk of Ydrad. He butted into our conversation:

“Well, you see, Heather, we all are close, but because we’re thrown together we need to give each other some space...”

He took a risk, saying this, because of course Heather could have easily retorted, “Then you give Dunc and me some space. We’re having a private argument.” But she was in too serious a mood for point-scoring. Instead she replied, “Stop being so general, both of you, and listen to what I mean. I used the word ‘huddle’ but I’m not really talking about any need to ‘huddle’...”

I suddenly understood what she was really talking about. If she had not been so proud, I would have stepped back there and then to give her a hug.

She wanted notice taken of her. She wanted appreciation.

That was it.

And she deserved to get it. It was highly probable that it was thanks to her, thanks to what she had given us, that we had so far survived on this part of the Slope. The totemic significance of the bandoleers, which made us “taboo” in the eyes of the natives, gave us the rank of some golden power, transfiguring us into a symbol of civilized glory. Definitely, we had benefitted from wearing Heather’s gift.

I was tactful enough not to apologise directly for having failed to give her due praise. It would only have upset her more. She should not have to admit her need.

The better way forward was for me to answer the charge she had made against me.

I ought to admit it was a fair point, that the more we were dominated by Slope and Sky, the less I became a “people-person”. By admitting that that charge was true, I could do Heather a favour, and I could do it tactfully, indirectly, changing the subject to my weaknesses.

I thought: Work round to it from very far away.

Mention the greatest journey ever made in the universe of the Earth-dream.

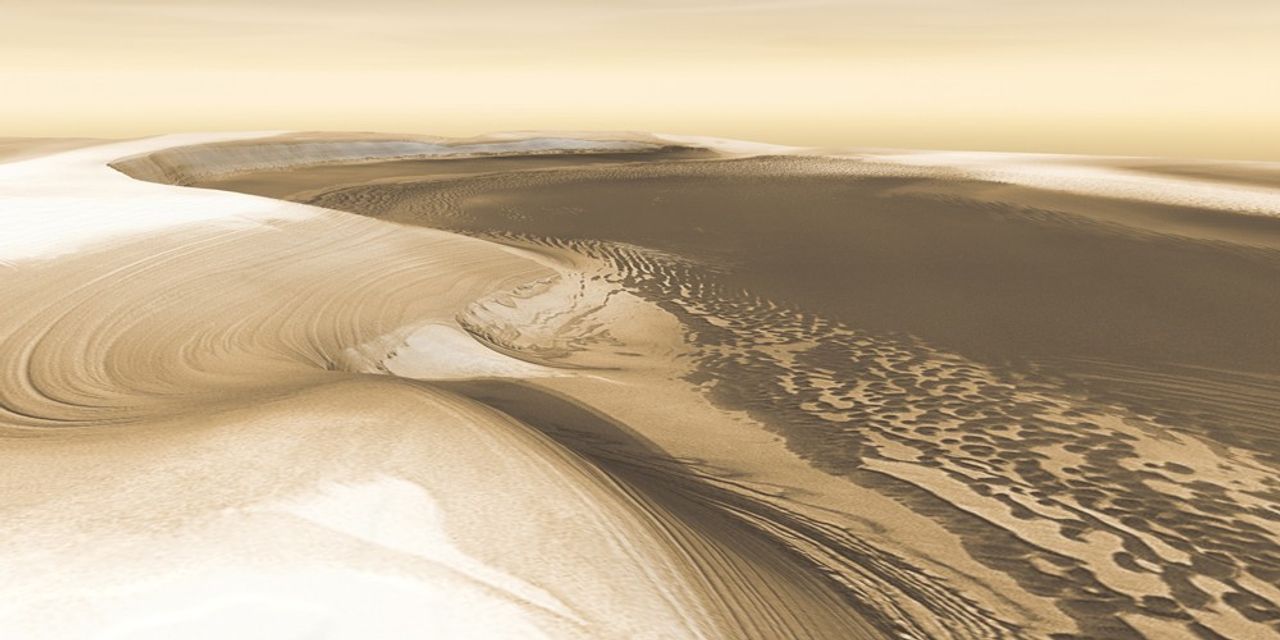

“Conspiracy theorists,” I said, “harped on the fact that you couldn’t see the stars, in TV transmissions from the Apollo expeditions, which meant, they said, that the so-called moon-landings were faked; that the spacecraft had never got to the Moon at all. You see the relevance,” I said, knowing perfectly well that none of my companions had a clue as to what I was talking about. They were gathered round, eager to guess the riddle. “The real reason those TV transmissions didn’t show the stars, was that they were on the Moon and so had to operate with filters, as otherwise they would have been swamped by the Sun’s glare, which of course is much more savage on an airless world. In taming that solar dazzle, the filters naturally can’t help but dim the stars into invisibility. Now, why am I telling you all this? Listen.

“Analogous to that bothersomely bright Sun on the surface of the Moon in Earth’s universe,” I went on, “is the fantastic brilliance of our aims, here on Kroth; the dazzling daring, stupendousness or stupidity or whatever, of our journey. For that to be bearable, the Slant must provide our filter. And the way that filter works for me – I don’t know about you – is to dim many personal things below the range of visibility, so that they’re lost like the stars in those Apollo transmissions...”

My voice trailed off. What was I doing, talking about the Moon? Kroth had no Moon. I couldn’t have picked a less relevant comparison for a Krothan audience –

Except that my audience was special. Far from ignorant. Vic and Cora had Earth-memories as good as mine, and Rida, who did not, was bound to be interested in comparative astronomy, it being his field.

So that left Heather as the odd one out. In other words, my choice of analogy had actually discriminated against the poor girl’s understanding... oh, well, pity I hadn’t come up with a better...

Then she spoke, and again she mentally pulled the rug out from under me, this time by sounding happy. “Earth-dreamer!” she laughed, and it was a nice laugh, “you could write a best-seller: How to Wriggle Out of Trouble.”

I was spared the effort of an immediate response: the ground underfoot changed just then. We reached a “ledge”, or more accurately the well-worn level north face of a “hill” projecting from the slope. This was a good place for a break. We had been looking forward to a break for quite some time.

...And now again my narrative fades out and now it fades in, almost a hundred days and a thousand miles later, with a snatch of conversation that can be sewn together with the one above; though the physical scene has greatly changed, our fears and our reassurances still circle us, like knife fighters probing for a thrust, only in slower motion than before, an equally serious but more leisurely discussion about big things, Earth and Kroth and life and culture and destiny.

“You two sorting things out again?” comes Rida’s voice.

Heather calls back at him, “Only a million questions to go,” in a tone of merriment which displays the loving comradeship that has developed, quietly over many days, between her and me. Gradually, imperceptibly, we have bonded into soul-mates. Not physical lovers – the situation denies us the opportunity for that, and suspends us without pressure or commitment, in a question-free glow.

“Well, give us a hand here first, will you...” says Rida, and I see that it has been decided to cut obliquely across-Slope and head for a ledge, again, for our bivouac. When we get there, Cora and Rida and Vic will want us to help with the unpacking. So with a few nudges to Ydrad I adjust our course towards our resting place. We move in a kind of Moon-walkers’ hop, our weight lessened by the counteracting buoyancy of balloon-plants, several of them tied to each individual’s backpack. Many days now, our descent of the Slope has been made gentler, less wearing for the muscles and knee-joints, by the use of these buoyant vegetable bladders, which we’ve named ploons. You see them growing in increasing numbers as you descend through this nether region of Slantland: their inflated tops, waving on the ends of their stalks, appear designed by nature to catch specks of nutriment drifting down within reach of their sticky frills. Natural analogues of helium balloons, when tied onto us the ploons bob above us and support and brake our descent; if it were not for their help, our journey would have become crippling, for by this time the Slope averages sixty degrees. Not much different from clambering down a cliff. No human mountaineer has the strength for an unaided descent of this sort – not if it goes on for thousands of miles. The ploons, however, make it possible.

Our destination ledge turns out to be about two yards wide, running past a cave. Caves are more common in these parts than they were in earlier stages of our journey. Quite often, in this region two-thirds of the way down from Topland to the Equator, the only horizontal space we find during an entire day is provided by some cave. This particular one with its adjacent ledge looks most convenient. Heather and I help the others set up camp in front of the cave mouth.

It requires care. No longer do we come across the wide hill-facings which we used to enjoy. No more sufficiently large flattish stretches upon which you can pretend, if you keep your eyes well down, that you’re on Topland or on Earth. The Slope is too tremendous, too dominant. Here there’s scarcely space to light a fire...

But the lack of level room is no problem for the decapods. Able to crouch contentedly on any gradient, they’re happy to let their bulk spill over the ledge’s rim. As soon as we let go of their straps, they begin to crop whatever scraggs of vegetation are in reach of their snouts. Marvellous, undemanding creatures.

The fire is lit, a snack set out; we relax and chatter, aware, in some corner of our minds, of the enormity of the scene. Repressed terror, muffled by The Slant, is never allowed to squeak out its message that we’re perched on a ledge of rock jutting from the Wayline at Latitude Thirty, Slope Sixty; that we’re almost shoved into space. Our emotions stay shielded from that outrageous truth.

We do, however, have to face a couple of lesser anxieties – “lesser”, that is, compared with the ultimate, Slant-squashed awareness of where we are.

For a start, there’s the practical danger: mudslide, scree-slip or rockfall. The gradient at sixty degrees is now so extreme that the danger of some sort of avalanche is ever-present. Indeed the downward crash of weighty matter has now smitten our ears on over a dozen occasions. We have sighted the smoke and sometimes the very dots-in-motion of distant crumbled slides. Only the fact that we haven’t seen or heard more, together with our ability to argue that the biggest loose rocks must have all fallen ages ago and that newer weatherings and loosenings must be gradual, give us reasonable hope that we will not be hit. But of course, natural processes are not the only ones to be feared. It would be terribly easy to start an avalanche deliberately.

Which brings me to mention our other major anxiety. We are now a long, long way south of the N’Skupurans, who believe that the bandoleer-things we wear give protection from hostile natives. It is natural to wonder whether the belief is still valid, this far down.

*

“If we turn out to be wrong about that cave…” I said, waving the stick of biltong I had been chewing.

We were all sitting cross-legged, facing the sky, and all of us but Cora had our backs solidly to the Slope. She, at the end of the row, was the only one of us who had her back to the cave mouth.

I continued, “Can you guess what I’ll lay the blame on?”

I wasn’t too serious. I did not actually expect anything nasty to come out of the cave. But every so often I considered it my duty to hold forth on some topic from an unexpected angle; not exactly as leader of this expedition, but as an arbiter, or at any rate a kind of mascot or figurehead. My companions had, I suppose, developed a kind of superstition that my Earth-memories gave me some crazy affinity with all kinds of weirdness. For some reason they latched onto this more than they did with Cora or Vic. Hence they listened to my punditry on this weirdest of journeys, this foolhardy mission to Udrem.

“Nobody wants to answer?” I prompted. I took another bite of the biltong. “Come on, picture it,” I went on, munching away. “Something appears, does something bad; and we blame it on... on...”

Still that silence. I must spell out my message:

“...On a disastrous inability to feel fear.” It was high time I shared my concerns on this subject. I grinned my Devil’s Advocate grin: “We don’t seem to be able to get scared nowadays, do we?”

Rida was solemn. “I see, it’s like we are missing some nerve-endings, yes?”

“Precisely! Precisely! Nerve-signals missing.”

Vic leaned forward, peered sideways and grinned back at me. He evidently approved of the way I stirred things up. “You’ve been mulling this over, haven’t you?” I nodded and he nodded. “Yeah,” he said, “I can see you have.”

“Then we must consider,” elaborated Rida, “that The Slant may work too well.”

Cora said dubiously, “That cave, it slopes up quite steep; it doesn’t look very habitable to me. I wouldn’t worry. Doubt if anything’ll come out of it. Hope not, anyway.”

“Indeed that’s just the point,” I explained to her. “We’re not worrying, are we?”

“Oh yes we are,” murmured Heather.

I glanced at her and felt a shock. How despondent she looked! Yet she had seemed happy enough mere minutes ago. But, then again, she did have these moods...

She went on, addressing all of us:

“Even now, I can tell, your thoughts are still busy with the Slant, obsessing about what it is, how it works, how well it works... and why do you harp on and on? I’ll tell you why!” (Her voice became crisp.) “You do it because... you fear you may wake up one morning and find your Slant is gone.”

Our mouths sagged open. How could she, how could our well-treated Heather, whom we had accepted into our group and into our hearts, say this thing? How could she even hint that our defence was not rock-firm? All right, maybe that was what we were really talking about, but did she not realize that to express the doubt aloud was to utter a spell which might let in the perpetually sneaky probing void? All right, I was prepared to admit that it was I who had brought the subject up. But you weren’t supposed to pick up the ball and run with it this way...

When a conversation is hurtling towards a cliff-edge you must grab control.

“Ah, but,” I drawled, “I’ve read plenty of science fiction.”

Vic followed my lead. “I suppose your SF reading prepared you for the Slant,” he suggested. “I know mine did.” His hearty grimace gave just the right accompaniment to his words. “I bet I’d have gone nuts, if it hadn’t been for science fiction.”

I must take the cue.

“SF helped save my sanity long before then,” I said gruffly. “In fact SF was far more vital to my mental health on Earth, than here.”

They were all listening quite calmly, and this, I judged, meant that the dangerous moment was past. So, now all I need do was steer the chat a bit further away from the idea that The Slant’s hold on our minds was insecure. Just a bit more tidying up. Some patter about the role of SF in preparing the mind for loopy realities on both Earth and Kroth. Then we’d be home and dry and conversational. But at the same time I wanted to seize the moment for my own purposes. I could not resist the opportunity. Happy as a hooligan with a brick in front of a plate glass window, I let fly.

“Books, all classic books, the ones I’ve known and loved for the years of my childhood, did this for me: they showed me, they taught me what people ought to be. Then along comes real life and what does one do?” (Hurl the truth at them!) “When, as a child, you think, from the beloved books, that you’ve identified the culture to which you belong, and they teach you to love it and be proud of it, and then, after those tales have set the standard, there comes – splat – real-life yuk – what do you do? Only one thing for it, after such a let-down. SF to the rescue! SF gives you an exciting reason for accepting that society is weird. SF...”

(“Contextualises,” Vic supplied a word softly.)

“...traditionalises that the world is going mad, that people are aliens. So yuk is no longer unbearably sad: instead, it’s an honest-to-goodness SF plot, whatever else it also may be. And so,” I finished defiantly, “in my capacity as founder of the Prigs’ Liberation Front, I hereby enlist the power of golden-age, classic SF – the only remedy for cultural nausea.”

At last, at last, splat it back! The custard pie was well and truly thrown.

“Perhaps,” offered Vic, “that gives a clue as to why you came on this crazy jaunt.”

At first I was grateful to hear any voice. After that rant of mine, a heavy silence would have been hard to bear. But then he went on:

“You wanted to make sure you were an SF hero, eh, Duncan? Instead of finding yourself in some mainstream yuk, eh?”

Right then I could have thrown a rock at his head.

“Don’t assume,” I said as I clutched at the controls of my temper, “that my grumbles about Earth can be transferred to Kroth. I’m proud to be a Toplander. I’m serving Topland.” (“Granted, granted,” agreed Vic.) “Topland has a future,” I went on. “With a country like that, a youth needn’t feel as if he’s growing up in Atlantis just in time to see his homeland sinking.”

“Like an adolescent dinosaur,” said my uncle lightly, “just about to get his life together when blam! comes the K-T extinction event.”

“Yeah, precisely,” I approved, forgiving him with a smile.

Silence fell, with honours even.

My pulse slackened; my mind ceased its combat. The peaceful conviction stole over me, that my words had won respect. Nourished by the breeze across our faces, and by the sky’s wholesome expanse, which seemed to scrub the slope at our back quite as fresh and clean as a windswept moorland on Earth, I judged that I had got away with my vehement speech against that disreputable old world.

Cora, however, said in her driest voice: “You should have got out more. You must have led a sheltered existence.”

The others didn’t chuckle; good, I could afford to ignore Cora. Vic was on my side. Heather and Rida, in their different ways, seemed placidly to accept my word concerning the yuk. They had no basis for counter-argument; they did not possess sharp Earth-memories of their own, merely the common Krothan interest in the tales and images which more expert “Earth-Dreamers” like myself or Cora or Vic could bring to life for them in a folklorish way. No great danger existed that the seamy side of terrestrial life could be communicated in such a fashion, or debated or called in question at all.

Seconds later, we had all gone silent. Our attention was wrenched towards the cave mouth, by a gravelly noise, a spate of clicks –

The subject of our talk forgotten, we watched as a pebble tumbled out of the inner darkness.

For some further moments we froze and listened. The single disturbance appeared to be all. A roosting bat might have dislodged the stone. Or perhaps an accumulation of water pressure somewhere had been responsible.

My eye caught Heather’s face. Just before she smoothed it away, it expressed terror.

“Tell me, Duncan,” she asked brightly, “what’s it like to fight?”

Not that again! She had asked me many times about the Battle of Neydio... but come to think of it, I’d rather re-hash that than parade doubts about The Slant.

“Fighting? You want to know what it feels like? I could talk for hours and still not get it right,” I mused. “You start off by wondering, ‘how can I kill?’, and then someone tries to kill you and that rips something inside you and you find you can do the deed, but it’s a kind of ruination...”

Vic’s sardonic tones broke in: “Don’t waken his wide-screen conscience again, Heather, for goodness’ sake! Panning shot of battlefield corpses; soundtrack of eerie whistling wind; voice over from The Lay of the Last Minstrel:

The phantom Knight, his glory fled,

Mourns o’er the field he heaped with dead.”

This time I was not a bit offended with my uncle’s cynical pose; I understood precisely what he was doing and I approved of it. To get Heather distracted from anxiety concerning The Slant was his priority, and mine. I’d done quite a good job so far, and now my role was to argue with Vic. Cora and Rida likewise understood the game – I could tell from their deadpan looks. Heather was the target beneficiary. Directed straight at her was our ploy to use one fear to counteract another. Any form of dread was better than the suspicion that The Slant might dissolve to leave us nakedly shivering in the truth of where we were.

Another slight sound; two or three more pebbles rolled out of the cave mouth. This time we paid almost no attention.

“Who knows,” I said; “we might have to fight. It’s not inconceivable.”

“Fight whom?” snorted Vic.

“Think!” I said. “This is the Wayline, after all. Ask yourself what that means. Why was this line chosen as the zero meridian in the first place?”

Rida intervened. “It happens to have a better-than-average flow of moisture down from Nistoom. A longitudinally fertile line.”

“Which,” said I, “therefore becomes a favoured haunt.”

“Of all sorts,” added Rida.

Crowd the mind with enemies! That’s one good way to forget the emptiness... but wait...

Vic, not being telepathic, didn’t get the ‘catch’ which occurred to me just then. “Oh, all right,” he said, playing the game as before, “I guess we’ll have to admit this is good roomy country for enemies...”

Sh-sh-sh... thought I. Too late, it occurred to me: an enemy might not provide an alternative to the emptiness. A really ruthless enemy – if he beat you – might well throw you into the emptiness... and that was the moment when we heard many more stones slipping down the throat of the cave.

The five of us began a backward crouching scramble, a retreat to our mounts, where we waited, poised (buoyed by our backpacks) in readiness to drop over the ledge-rim behind the beasts, if necessary. Vic unpacked his pistol. I fumbled for mine. I wondered, scattily, whether I was about to see a mungonst, a mythic bogey of the corries and caves. A few days back we had learned about mungonsts from Heather. A difficult matter it was, at that moment, to keep my thoughts under control. This inner jumpiness made me suspect all the more that we might indeed be close to losing The Slant, our one and only mental protection. The next moment a twinge, a jab at the back of my neck, made this worry obsolete.

*

Had a hypodermic pricked me, or a blow dart? The latter, maybe, since a few seconds elapsed before I was reached and seized. I was lifted, and taken over the edge. I tried to cry out but I had gone numb; my sight, moreover, had faded into a milky blur – but I could still hear: not voices, but an effortful breathing, as my captors enveloped me in a kind of sling and carried me downwards between them. Were my companions taken likewise, or had I been grabbed alone? No way to tell, as I swung this way, swung that way, like a package borne by loping mountaineers under lunar gravity.

Normal eyesight returned to me after a minute or so, though I still felt too sick to move a muscle. My field of view was three-quarters restricted by the sling and further confused by the motion of our descent, but I glimpsed a hood worn by one of my bearers. My optimistic side reasoned: “These folk hide their faces – so they want their identity kept secret from me – so they intend eventually to let me go unharmed.” Then my pessimistic side snorted back with, “Oh, so hoods are reassuring, are they? Tell that to the victims of the Ku Klux Klan”, and other images and scraps of knowledge swarmed into my mind, stories of unspeakable things done by tribal societies to their captives. My optimistic side - determined to stave off panic by conscripting any idea, no matter how pitiful - countered with, “Well, look at it this way, after all, this is free transportation in the direction we planned to go!” Borrowing, in fact, from the pseudo-courage lent by The Slant, I tried to insist that everything that happened must serve my purpose, must be all right. This dishonesty succeeded, for the moment: self-deception, as a substitute for guts, helped me to keep my head. But such stratagems are not durable. After about half an hour I was hard put to it to stave off the sense of misery, loss and foreboding which anyone who is kidnapped cannot help but feel.

At last my bearers halted, and then they lowered me. I was draped, cross-Slope, with my stomach against a projecting tree-stump. Like a scarf hung on a hook, one half of me flopped down one side, the other half on the other side.

Still cocooned in the sling in which they had wrapped me, I could not twist round to see them, but I could hear them talk, and the more I concentrated, the more I began to understand their guttural, thick-tongued English.

“Clever, Yaghedd, clever to fill the bag.” It was the voice of a flatterer, hoarse but sly.

A grunt of unconcern, perhaps of disdain, was the next sound I heard. Doubtless a snub from a superior.

The first voice, not in the least put off, continued its oily rasp: “Perfect diversion, perfect snatch – third time lucky, eh?”

“My business, Tolod.”

“Of course, of course. You’re the one who has to report to N.D. But we both know what the ‘business’ was, don’t we? Uncommonly good, this lad’s speech –”

“Don’t say it, Tolod.”

“– about Fear.”

“You disappoint me,” breathed the owner of the superior voice – the one called Yaghedd. “Do you want to be pegged?”

“Sorry, sir,” said the other, and that was that, for a while.

But though Tolod might not relish the thought of being pegged, any more than I would if I knew what it was, nevertheless I pinned hope on his insubordination and longed for my enemies to fall out with each other and leave me free to escape, for I was confident that I could worm my way out of the “cocoon”, given time, if I were left alone to try.

After another minute or so I was lifted again, to be carried downwards again. The swaying journey resumed, as before, except that now I kept wishing I could somehow influence Tolod to have another go at needling Yaghedd. But even if my voice had come back to me, I had no idea what to say. And it turned out there was no second chance; the next stop, half an hour later, was quite different.

I was placed on a kind of seat and I heard a click as fetters were locked round my ankles. Then the enveloping coccoon-sling was removed from around me and my vision could rove at last. My eyes blinked at multitudes; my ears caught the chatter of thousands of voices blended almost into a roar.

Perhaps, by now, I was able to speak, but who would hear me? My two captors had melted into a vast crowd. The sun had dodged around the corner of the world and I was left with a few minutes to make use of the failing light, to comprehend the scene.

I had been set upon a tree stump for a chair. We had halted on a ledge which gave us ten yards of horizontal room in the north-south direction and what looked like half a mile or so in the east-west direction. On this ledge and on others above me, wherever I looked I saw figures in the process of departure or arrival or the arrangement of blankets or the preparation of food, or seated cross-legged, or standing upright, or recumbent, but all in some sense “perched” and waiting. It was suddenly hard not to think of them as a colony of birds – puffins or gannets, maybe – rather than a crowd of human beings. As the dusk deepened, survivors’ instinct made me hasten to concentrate, to pick out details, though it was not easy to believe that my wits would get me out of this. The men, the women and the children all wore their long black hair in a ponytail that swished as they moved their heads, they all wore hoods and cloaks, and they were all intimately attached to ploons that fitted in arcs round their shoulders, magnifying the upper halves of their bodies. The comparison with birds became stronger. Why, though, were they all gathered here? Was this ledge the capital of a birdman empire? Then, perhaps two hundred yards westward, due to part-dispersal of the crowd at that spot, I caught a bare glimpse of a platform, and of four or five figures apparently lying stretched upon it. For a moment my blood froze; then I ceased to try to strain my eyes. Darkness had fallen too far for meaningful observation.

I spent a most uncomfortable night, forced to sit up and (so I guessed) be softened up for what awaited me on the morrow. And in addition to my restricted physical position, and my uneasy thoughts about being pegged, what I heard brought up further disturbing possibilities.

In the same way that the wind often dies at dusk, so the din of voices lessened, but it did not cease; it changed its character.

I heard – without, at first, believing – one voice mutter:

“...public prosecutor …air battle …exodus …fluctuation…”

Another voice overlapped with it:

“...anchor ...drill ...anti-aircraft ...dining-car...”

Another:

“...typewriter ...contamination ...disarmament ...rail network...”

And another:

“...helmet ...pulpit... coastguard... fax machine… nature reserve... typewriter...”

And more:

“...typewriter… beach holiday ...spreadsheet ...nuclear reactor...”

“...steering column ...recrimination ...informer ...highway code...”

“...breakdown ...typewriter ...boss ...magazine...”

“...pine-forest ...building-site ...mugging ...typewriter...”

I wanted to scream out my need for an explanation, to avert the terrible creeping horror of the suspicion that the universe had no meaning and that the veil of pseudo-meaning had been ripped away to reveal this stark fact. No – it could not be – everything must have an explanation, even if the explanation consisted only of randomness. But why did randomness take this form here, in this place, in this darkness: why was it expressed by people who recited as though they were dictionaries with mouths?

“...price control ...refuge ...cancer ...consultation ...by-election... Hardship ...frontier... stock exchange... typewriter...”

The hours went by, the night advanced and the dictionary-voices became fewer and at last tapered off into blessed silence.

After an unmeasured interval I heard a different kind of voice; a howl of pain, coming from the direction of the platform I had seen to the west. The pain-noise lasted a minute or so and then died down. It repeated itself six or seven times before morning. Naturally it filled me with dread but I could understand it, I had heard of torture before; the other phenomenon, though, the random words, was less ghastly but creepier. Especially the favoured word, ‘typewriter’. Why was it favoured? Obviously not for any literal reason. Slang? ‘Typewriter’, as I knew from the adventures of The Saint, was 1930’s gangster-ese for ‘machine-gun’ – not applicable here. For lack of anything better to do, I scrabbled on in vain for a purchase on the mystery, till the sky at last began to brighten around the eastern cliff of the world.

*

Dawn broke to find me in a bad way, shivering with exhaustion, aching, hungry, thirsty and too jumpy for an attempt at fatalistic resignation. The distant yells of agony had ceased towards morning, but now they had resumed. Meanwhile my dulled, twitchy brain took in the fact the perching crowd had thinned. Greatly thinned, to some hundreds instead of thousands.

Two men approached. I guessed, correctly, that they were the ones who had brought me here.

One of them knelt to undo my fetters. The other planted himself in front of me and said: “I am Yaghedd of Tokropol. Speak your name, if you can.”

“Duncan Wemyss of Topland,” I croaked.

“Stand up, Duncan Wemyss.”

I tottered. Yaghedd gripped me by the right bicep and began to conduct me westward along the ledge, in the direction I most desired not to go. Stepping over the forms of those who were still asleep, and weaving around the groups of those who squatted at their breakfasts, we made our way through what was left of yesterday evening’s great crowd. At one point Yaghedd had to wait while I doubled up with cramp. Then he forced me to continue as before. Even if I had not been as weak as a kitten I would have been no match for his silent ruthlessness. One thing I could and did do –

I opened my mouth and repeated:

“I am of Topland.”

“Indeed,” laughed Yaghedd, “I heard you.”

Perhaps others, too, had heard or guessed; at any rate the crowd seemed aware that an alien walked in their midst. Yet something restrained them from displaying normal curiosity about me. I caught many sidelong looks, but few straight stares. On just three or four occasions, people did openly gawp with expressions of greed and longing, which I hoped signified metaphorical hunger only. Yaghedd dealt promptly with these cases: he lifted both hands together and then abruptly spread them apart with a slicing or ripping gesture. Thus warned, the spectators dropped their eyes.

Finally the crowd thinned away altogether; the scene opened up to a clear view of the nightmare ahead.

We had reached the platform that I had glimpsed the previous dusk. Now the morning sun shone on the five pegged victims. They were skewered to tree-stumps in a manner which I shall not describe.

Yaghedd brought me closer. We halted a few paces from the stumps.

“Why?” I whispered.

To my dim surprise, Yaghedd replied quite gently, softly. “It’s not too late foryou. Come, let us patrol.”

As he conducted me among them, tracking slow figures of eight around the stumps, the victims’ pain came and went, minutes of yelling agony punctuated by minutes of an odd calm. Alongside all the horror that I felt, came the mounting suspicion that these people had been drugged with a substance that affected them intermittently, and that perhaps they were not criminals or enemies but, instead, some kind of prestigious sacrifice, respected even while tormented. This perhaps lessened the horror from their point of view, but it did not at all diminish the peril in which I stood.

We halted in front of one victim who, I had just realized, was staring at me more fixedly than the others.

This individual might have been taken for a prosperous storekeeper on Earth; even here, his roly-poly face, sweating with agony, retained a kind of sociable wit.

“Ah,” he gasped, “allow me to guess, Yaghedd: you have come to offer me a swap.”

Yaghedd smiled, while I trembled. No no no, I selfishly willed, no swap: I am not going to change places with him...

I need not have concerned myself on that point. The “pegged” man, without waiting for a reply, continued:

“Neither myself, nor any friend stuck here, would exchange our...” he smiled, winced, panted and continued, “incommodious state for that of this young man... if he’s headed where I think he is.”

Yaghedd shrugged. “Very well, Olonn. I simply thought it might be worth a try. But if you’re sure...” He gazed around at the others.

One of them shouted: “Olonn’s right. None of us is such a fool!”

“Come on then, we’re wasting our time here,” said Yaghedd to me, and marched me further along the ledge, into an area devoid of population and empty of feature. By now my feelings of terror were close to unmanageable, as they closed in around the one remaining command post in my personality – the citadel of trust, flying the flag of reason, proclaiming that answers did exist, that they could at least in theory be found. Where were those answers? Where were the insights that could save me? It did not seem that I was in any condition to outwit what was on the way, whatever it was – all I knew was that even the pegged would not swap places with me. I could hardly walk, hardly think, hardly even feel much except the shrunken dribble of my allotted time.

Not far ahead of us the ledge disappeared from view round a pleat in the tilted surface of Kroth. When we turned that corner, I beheld a structure that loomed across our path with finality.

Yaghedd echoed my thought. “The end of your road, Duncan.”

I knew he did not mean the red hut with walls and octagonal pointed roof which stood a hundred yards from the bend. As we walked that way I gave only small attention to the hut, and to the rather beautiful Slope-gardens tiered above it. What drew my eyes was the simpler shape beyond: a boulder, six times man-high, dramatically, artificially poised, right on the edge of an outcrop.

The shape and location of that rock had to be artificial – I could instantly see that it must have been carved, slowly and deliberately, from the outcrop. Before the hand of man had touched the area, there would have been nothing special to see at that spot: just another pleat in the Slope. Then (the job must have taken generations) most of the material had been chipped away to sculpt a platform with the bulky isolated rock balanced hair-raisingly on the edge. The alternative explanation was that some natural process of geology or weathering had placed it just so – but that was not credible.

We approached the door of the hut, which, like the walls and roof, was covered with a mat of red feathers. The door stood slightly ajar. Our footsteps, I suppose, were heard within, for the door opened fully before Yaghedd could knock.

A man close to seven feet tall with the size and build of a Sumo wrestler, greasy black ringlets and a scarred face, stepped out of the hut and gazed down at me with a remote expression. His immense shoulders were made even broader by the arc of the ploon which was fastened behind them; in view of the man’s bulk I wondered, idly, if any ploon could slow his fall to a useful extent, if he were to topple off the ledge.

Distantly mild, his voice spoke: “Well?”

Yaghedd bowed low. “I imagine, Narth Drong, that Duncan is now as fit as he will ever be, for the Choice.”

At this point I got reckless. “I haven’t had much ‘choice’ so far,” I muttered, too punch-drunk to worry about how the opposition might react to my bit of cheek. But then I heard my own words and the truth came to me in the pale blue glare of Narth Drong’s eyes – the truth that it was now or never. I had created my little moment of surprise and I must seize it. A statement, this instant, must issue from my lips. An influential, powerful statement to set me onto the path that would lead out of the fog of mystery, back into the sunshine of sanity.

It was a path which I might never have found, had I not been stirred to the depths by physical and mental stress. What came out of me then was a childish sound, a naïve complaint:

“This is not a very nice part of the world to live in, I think.”

Once again, after they were out of my mouth, I reviewed my own words with astonishment, an astonishment which increased as I realized that my enemies were listening. Could this be why I had been brought here? I babbled on, and as I did so I heard in my own words the mystery spooling out of its hiding-place.

“You people here in Tokropol have to make do with few things. Life is, shall we say, restricted around here, eh? You hunt around the cliff for food, you grow some, you raise your families and life goes on, and that’s about it. Can’t build much of a civilization on a gradient of sixty degrees, can you? But then there is – was – the Earth-dream. It’s fading now. You’re trying to recall it but its terms are losing their significance. Just words, now. Drained of their colour, their vividness, their life’s blood. No good any more. But you people repeat them, anyway; it’s all you can do. And you hope to hit on an occasional jackpot word that does still mean something vivid. I wondered about typewriter.”

I paused for breath at this point. My enemies stood erect, stock still, not tired at all. Their wits, keen as knives, were ready to punish one false move on my part, now that I had reached the narrow place in my argument.

“Typewriters are long out of date,” I went on, madly calm now. “It’s all computer keyboards these days. That fact ought to be quite as evident to Earth-dreamers on Kroth, as it was evident on Earth itself. But one particular use of the older word is still current. The proverbial thought-experiment, to do with the laws of chance. How long would mere chance take to type out the works of Shakespeare? Set it up. Clack-clack-clack! Monkeys with typewriters...”

“Enough,” pronounced Narth Drong.

And then he repeated the word in a changed voice, more like a sheet of canvas being ripped apart. He appeared at that moment as though he wanted to tear me apart, which he could easily have done, except that I could tell (I had the sense not to smirk) that he could not help but admit the truth of my insight.

I had lurched abruptly from zero understanding to the opposite extreme. It was one of those moments in my life when the dead-right guess flashes into my unpredictable noddle like a picturesque spike on a graph. The stab of comprehension enraged Narth Drong while at the same time it made him hesitate. The seconds ticked by and I still lived. But for how long – that, I could not guess. I now knew that Narth Drong was no mere chief, restrained by the customs of his tribe or federation of tribes; he was an absolute monarch, likely enough the embodiment of Henry VIII, Caligula and Genghiz Khan rolled into one. I lived moment to moment on his sufferance. So did all his people. And they wanted it that way, because –

*

I “came to”, groggily. With some wriggling and twisting I soon worked out where I was.

The window of the conservatory, on the far side of the hut from the entrance door, extended down to the tiled floor on which I lay, gagged and bound at ankles and wrists – my hands behind my back. Through that window I would, perhaps this very day, witness the crime of the age...

I shivered from weakness, from low blood-sugar; also I ached from a bruise on my head. He must have walloped me, after all. But because he possessed some self-control, I was still alive; if he had vented his full frustration he would have snapped my neck like a twig.

Poor tyrant, expected by his people to commit the crime they dared not commit themselves. He was the chosen instrument, the receptacle for their hopes. The hoped-for typed-out jackpot scapegoat. (My poor pummelled brain fairly bled with insights now.)

After a while the conversation began. I could overhear the voices quite distinctly, through the wall behind me. It was such a pity that I could not concentrate my mind on them; it was all so important, yet I let it slip by. Then there was a lull, and I felt guilty and sad. Aw, come on, I muttered behind the gag. If a couple of little hobbits could penetrate to Mount Doom, surely I could do better than this. Especially as my plight was about a lot more than just me.

Out there the poised boulder loomed, close enough for me to examine the adjacent structures at my leisure: the mount for the fulcrum, the long lever slanting away from it, and the derrick-like stand for the operator at the other end...

I made a supreme effort to clear my head.

The talk resumed.

*

“Have you decided,” said the wintry voice of Narth Drong, “whether to believe me?”

“Oh yes,” replied Uncle Vic, “I believe you.” (I could hear his sincerity right through the wall.)

“Then perhaps you will understand,” the tyrant continued, “when I tell you that one person does exist, of whom I am afraid. That person is myself. I may do it. I would much prefer someone else to do it, but I may. If necessary. If all my chosen candidates spurn the honour, and would rather die pegged than obey my will in this matter. If – and I say this to you in confidence – if I continue to lose trust in my people... Do not misunderstand me, Toplander. They will never rebel. But neither, perhaps, do they have it in them to co-operate. Which leaves the task to me, unless...”

“You are talking in circles, Narth Drong,” said Vic, and I marvelled at his courage, while at the same time I admired his wisdom and trembled at his rashness. I myself had done my small bit; I had planted, in the brain of our enemy, some seeds of respect for Toplander insight. Henceforth it must be up to Uncle to do the necessary cultivation and get us out of here, if that was humanly possible, which I doubted very much. He continued:

“Let me assure you, Narth Drong, of what is plain to me, so that you can trust me not to waste your time. Your people are yours, body and soul, except for the one matter to which you allude. They are in subjection to you because they choose to fear you. Your unpredictable will is the one spot of colour in their monotonous lives... It is not idle to compare you with someone who once ruled a great country in our world. He became known as Ivan the Terrible. Many of his subjects, those who survived his rule unscathed, actually admired him, and we know, for a fact, that when at one stage he wished to abdicate, and went so far as to withdraw from the capital, a host of suppliants went to fetch him back... they implored him to resume the throne. And so he did.”

“Well spoken, Toplander. You see my problem, do you not? If, even with this level of loyalty, I can go no further, I must alter my plans, I must use other tools.”

Most likely, I was intended to overhear this. Narth Drong was hedging his bets.

“Guilt,” said Vic, “is, I take it, the problem?”

“Guilt,” agreed the quiet, grim voice. “It would not be fitting for any of my subjects to hear me say this openly. But it is true, that though I fear nothing else, I fear to pull that lever. Everyone has his limit of courage.”

“And why must the lever be pulled? I know, you have said that Plim must be fought. Is this the only way?”

“It is the way prepared by generations. It is the culmination of the efforts of the ancestors of my people.”

“I know, but…”

“Are you suggesting, Toplander, that I should alter the plan?”

“I am trying to save you from remorse. Ivan the Terrible also suffered remorse, many times.”

“And so it appears that you do suggest that I alter, that I abandon the plan.”

“No, no,” stuttered Vic, doubtless aware that he might have gone too far. “I understand the commitment.”

“Then,” sighed Narth Drong, “the moment has come to fulfil it.”

I shuddered and cringed at the sound of footsteps. The conservatory door behind me opened. I feared the tyrant, but I feared the crime more. I fully understood why so many of his people had preferred to be pegged rather than agree to pull a lever which would launch an unstoppable destructive avalanche that would blast and score its way down thousands of miles with the likelihood of megadeaths. The equivalent on Earth might be to press the button that launches a nuclear missile. The guilty party must face the wrath (unbearable, whether real or imagined) of a million ghosts hungry for revenge. Here on Kroth the special scruples against gradient-crime threatened to make a hero out of the most unlikely material – yours truly. I could hardly believe it, but I knew that I would and must refuse, if it came to the point and I was chosen. And it would come to that point, wouldn’t it? Vic wouldn’t do it himself, would he? He wouldn’t co-operate with the monster, would he?

They came through the room and stepped over me. Vic looked down into my eyes during that briefest of moments and his expression certainly did not give me the reassurance I craved.

Narth Drong unlocked a glass door, an opening in the style of a French window, and stepped out.

“Wait, ruler of Tokropol!” called out Vic.

With a gasp of hope I made futile, muffled sounds behind my gag. Vic had some answer after all – I could tell the signs – but the about-to-be genocidal murderer had begun to stride away in the direction of the instrument of mass destruction and I could imagine no way he might be forced to stop and listen. In the general agony of failure I squirmed as though it were my fault that I could not heave events back onto the right course by force of will.

Vic shouted louder: “I can tell you a way to become the Master of Fear!”

Narth Drong, to my stupendous relief, turned, stopped, spoke:

“Say on. Make it your last argument.”

“It is the last. Trust me – I have an Earthmind, and I know – the way was pioneered by one of the decision-makers of Earth. Recorded –”

“Who was he?”

“The decision-maker? An adviser named Guido da Moltefeltro. Properly recorded in a – er – treatise, perfectly apt for this kind of situation.”

Narth Drong turned his eyes towards the waiting boulder, and I could guess his mind. This kind of situation? Could any previous one have matched it? Was the Toplander offering from experience to make it easier, to become the Master of Guilt-fear?

All my emotions were turned up to white heat: both heart-rending hope and hideous doubt. I no longer trusted Uncle Vic. Of course, he had been obliged to say something, anything to win a moment’s respite. Our enemy had at last made up his mind to pull the lever and take the consequences, so, yes, to play for time was justified, but...

“Guido planned to do a bad thing,” Vic explained, “and yet to make repentance part of the plan. Do the thing and repent of it, simultaneously. Bring that into your plan, Narth Drong, and you can cancel the remorse!”

If it were not for the gag I would have screamed for these words to be withdrawn, but only a whimper got out, and meanwhile I had to watch a smile spread over the platter-sized face of the ruler of Tokropol. No match for Vic’s sophistry, the simple-minded monster turned again and lumbered up the stairs to the platform where he straightened and cupped his hands round his mouth and yodelled: “YAIRDLEE-YOOOO...”

I felt a twitch between my shoulder-blades and reflexively my head turned as far as my neck would let it, but of course I was in no position to see who might be creeping into view of the platform; I guessed, however, that it would not be much of a crowd, merely a few acolytes or trusty servants who could be used as witness or else disowned, according to how events fell out, after the atrocity for which the moment had now arrived.

The tyrant cried out, “Glorious Glondeem! Rahha! Rahha! Glorious Glondeem!” – and, in slow irrevocable motion, he pulled the lever.

I had a brief crazy hope that the thing would not work, but then I heard, and more strongly I felt, an almost subliminal grate and splinter of lesser structures on the far side of the boulder, as it began to move. That instant for me was the deaths that it would bring; the deaths already written in history, insofar as what had begun could not by any means be stopped.

The great mass lurched over, began to gather speed as it toppled and sank past the edge on which it had stood. It happened in a hateful quiet, though the ground quaked at the shift of burden, and for those who lived in the path of destruction I could well believe that the doom would announce itself loudly enough; the echoes of it, the pictures of all the probable effects, rebounded through my imagination.

My fit of the horrors had not yet bubbled away when Narth Drong stooped over me. He was grinning a happy grin, and holding a knife.

*

“That was the nervous moment for me,” Vic remarked. “But I was fairly sure that he would release you, would release us all.”

“Ah,” I said.

“Well, what else can I say except to ask, how would you have handled it?”

How indeed. I had no good answer.

In any case, in a practical sense matters had turned out so well for us that I could hardly find it in me to complain. My gratitude at our escape ought to have been overwhelming. It almost was. I could savour the continuation of my own life and the presence of my companions, whom I had thought never to see again. I could rejoice in my renewed appreciation of their qualities: Rida’s reserved decency, Cora’s impudent warmth, Heather’s loveliness which was apt to make me short of breath, and Vic’s many good points which still shone through the curtain of dismay drawn across them by his latest act. Visually, it was as if the clock had been put back to before all our trouble with the Tokropolians. Here we were, the five of us reunited, moon-hopping down-Slope as before, free and unscathed. Even our beasts had posed no problem: it turned out that Ydrad, Gnarre, and the two decapods appertaining to Cora and Rida had simply followed us down, perhaps merely due to some southward migratory urge, although a sense of personal loyalty, where their mysterious natures were concerned, could not be ruled out. Narth Drong had helpfully passed on to us the reports from his scouts that our ‘pack-steeds’, as he called them, were close by.

The tyrant of Tokropol, full of good nature, had watched us re-group and bade us a courteous farewell as we set off once more on our journey.

I made up my mind that I would have one try at answering Vic’s question. Just one go at getting through to him the fact that, to a normal, sane, wholesome, gradient-wary Krothan, a point exists beyond which ordinary evil will not go.

“The thing is,” I faltered, “the damage is more than just the rock. We now have the choice: stop thinking about it, or go mad. And we can’t afford to go mad, so we have to stop thinking about it, and so – we’ll become less than we were –”

“Ah, stop worrying,” interrupted Vic breezily. “He was going to do it anyway, so all I did was convince him he owed his clear conscience to me. That got us out.”

I looked at the others. They wore expressions of grave agreement. They sympathised with me – and with him. Sympathy all round.

I knew that I, too, would just have to accept the inevitable. The awareness of it, which could not be effaced, I must store to one side.

That meant, among other things, getting along as normal with Vic, and trying not to think about what else he might do to the world. Insofar as I could manage that, I would be the Master of Fear.

>> 4: The Last Ledge