kroth: the drop

5: udrem

During the final fortnight of our descent, through the bird-thronged sky, our journey was less rational than ever, more than ever a fated thing that held us in its dreamy grip.

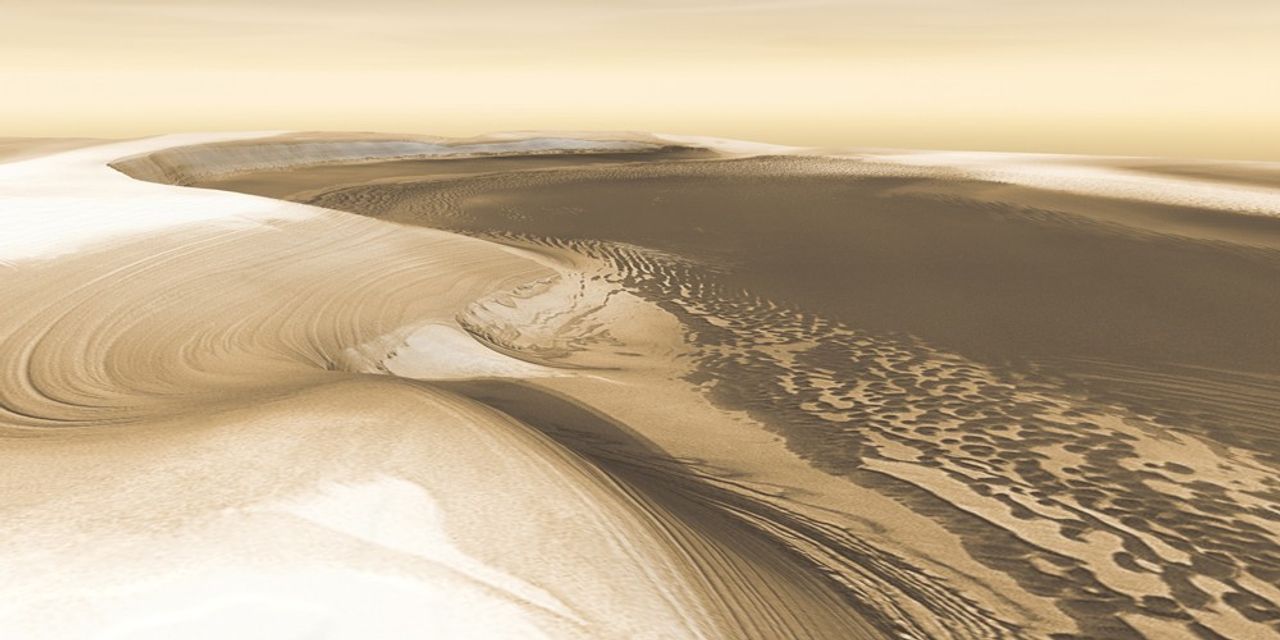

The greater part of my day was spent facing the vertical belly of the planet as my eyes and hands were occupied with the need to grasp and feel my way down successive tufts and footholds, but now and then, when I needed a rest or got sick of the wall in front of my nose, I would pause to look into the distance below. This meant staring into the limitless blue which split the scene fifty-fifty with Kroth’s equator. Or I might twist my body round and look outwards into space so that, rather than the azure below, the identically coloured vastness of the rest of the universe met my eyes. And at night, from time to time, I peered over the edge of my hammock (slung between two bushes) and gazed at the stars which shone eerily below me, or I might look up the seemingly infinite cliff wall, towards the civilized northern latitudes now hidden from me by the curve of the planet.

Then my mind might try to play with the faded idea of those blessed regions where the Slope was milder, those special, amazing realms where a man could stand on ground, could walk instead of cling... “Stand”, “Walk”; “Ground”; quaint concepts! Experiences which I missed only vaguely, not sorely. In place of that old way to be, the views around me had a new normality. Fantastic though they were, they were firm and true, and met with my yielding acceptance.

However, as our destination came into closer view, I began, slowly, to gather my wits.

Came a moment when I blinked, and groggily wondered: exactly how far did visibility extend around here? Re-awakened spatial awareness roused me.

I was being prodded to make judgements. Precisely how far could we see, and thus be seen, on this wallscape?

Such moments of rusty awakening occurred more and more frequently. My creaky mentality, my decision-making machinery was being oiled, though, at the same time, a sort of buzz in my head signified resistance – for change meant disturbance. And it’s not surprising that I didn’t like it.

Imagine, if you can, days spent clambering down between wall and sky, the overwhelming simplicity of two, just two, boss-things, wall and sky, unless you count the circling sun as a third – but now the smudgy hint of Udrem, far below, is perhaps a future fourth thing. Infinity has edged back, to allow room for a lesser something, a mere hugeness, a measurable, though vast, Equatorial jungle.

That was the next stage of our adventure. That was it, waiting to receive us. My cosmically doped mind found it a chore to contemplate this destination. I did not wish to go back to being bullied by sizes and events. I hankered instead after a continuation of the friendly quiet foreverness which had enveloped us for so long. Why couldn’t we go on as we had when we had to do nothing but climb down a landscape tipped at right angles seemingly without end? Such a pity, that the holiday from dimension must end soon.

While my woozy mind tried to cling to its trance, I nevertheless made some effort to formulate intelligent questions. I dimly realized that a point must come when my present state would have to end. Some of my more extreme mental adaptations – aspects of “The Slant” – would then have to be uninstalled.

What with one pressure and another, I sought to compromise, to ease myself in gradually to the world of sizing-up. In such conditions the eye can start with a hunger for small objects. Such as... my companions. They were good to look at. They were human-sized. Unfortunately, like me, they were stupefied. Their silence confirmed the overwhelm. Ironically it was during this last lap, when we could actually glimpse our destination, that we each of us retreated furthest into ourselves. I almost forgot the names “Vic”, “Cora” and “Rida”, and eventually I might have forgotten that “Duncan” was my own name – but because some sort of end was now in sight, because the blue-grey strip crossing the wallscape far below us increased very gradually in size and definition, I strove to concentrate.

I opened my mouth at last.

“Rida,” I called to our scientist.

His lanky frame hung a few yards to the east, his tummy facing the world as mine did. We both were clutching the same kind of fernlike outgrowths, and in both our cases, if we had let go, we should probably have been saved by the vegetable balloons which gave buoyancy to our backpacks – at least, they would have given us a minute or two in which to regain our hold on planet Kroth.

Rida turned his face slowly to his left, in my direction.

With a fierce attempt at concentration I stared at the black pencil-thin beard which ran round his jaw like a little strap (he still shaved carefully round it every day), as I willed him to answer.

The mouth opened and words croaked out. “What is it?”

Thank goodness he was alert enough to hear me. I asked, “How many miles do you think we have still to go?”

He took two or three heavy breaths and gave me a dusty answer. “I am unwilling to name a figure.”

I was so relieved to hear his dry voice again, all the more welcome for being verbose. A scientist had spoken, and I was reassured. I listened as he muttered on:

“No easy matter to gauge the range of our vision as flies on a planetary wall...”

Uncle Vic, whom I tried next, was on my other side (the west) and a bit further off. His torso hung like some huge pear from the branch of an outgrowth over which he had hooked his left arm as he turned to listen. He, too, came reassuringly to life when I addressed him. “If that smudge is really Udrem,” he boomed, “and I don’t see how it can be anything else, it is probably about a hundred and fifty miles down from where we are.”

Rida laughed raggedly. “A good guess, I suppose. You are more willing to stick your neck out than I am.”

Meanwhile his woman, Cora, with pantherine grace, pulled herself sideways from one to the next, reached over and laid a hand on Rida’s arm. “We’ll get there,” she soothed. “Until then, enjoy the bright sunshine, while you can.”

I made up my mind never again to ask how far we were from what Vic had termed “that smudge”. In fact I hardly needed to, for as further days went by my judgement of distance improved. Experience in our fantastic environment made me at least the equal of my companions in that respect. Admittedly, my beliefs did waver, on occasion: so gradual was our approach to Udrem that I sometimes wondered if it were merely some cloud belt and not a solid jungle at all. But then again there were the birds, the wheeling, cawing birds, and the knowledge that all the authorities agreed that a hot web of life did girdle the equator of Kroth. Here was the region closest to the sun and broadside to its rays; already we had had to strip to vests and shorts. It was an invigorating heat, which put me in mind of the breath of life.

Besides, we came across the trungs…

*

Had we heard the word from native cliff-dwellers higher up, in previous weeks? Or had Heather once mentioned it, on one of the occasions when she had chatted about legends that came up to N’Skupur from the south? Or had we ourselves coined the term? I could not remember. Anyhow, it was easy to guess that it derived from English, being simply a contraction of “trampoline fungus”. To see was to understand; and to smile, too, if one recalled the proverb, “walls have ears”, for definitely this wallscape had an ear growing out of it, or at any rate a thing shaped very much like an ear. Four feet across, it was spread to catch not sound-waves but food: organic material of all kinds, anything animal or vegetable that fell from above. A trung’s structure is so tough and flexible – not at all brittle like ordinary fungus – that it can break the fall of an object more massive than itself. The centre of the trung’s “ear” is a flap designed to let inorganic stuff through (stones, pebbles, clods of dirt) while clinging adhesively to edible matter (corpses and the remains of plants). Moreover when the structure is hit by objects that are too big for it to accept, it has an elastic ability to bend with the blow and right itself afterwards, as we witnessed of one of the larger trungs a day or so later. We eventually passed some which were fully nine feet across. I even wondered if a human might be able to use one as a real trampoline, if the stickiness were removed.

More importantly, trungs, if they grew densely enough, could provide protection against rockfall. Already it was obvious that the areas underneath the larger trungs were richer in plant-life than elsewhere. It stood to reason that this was because those areas were sheltered. That got me thinking. Safety... danger... shelter... rockfall, or any heavy object’s fall... down from our zenith, down the face of the world; you’d never see it coming, you’d never know –

So far, we had merely trusted to luck. What else could we have done, so long as we knew that there was no defence against that danger? But now, if safety became an option, danger became avoidable, and hence a worry. It became worth thinking about. I began to slip into the frame of mind whereby I sought to observe trungs and looked forward to cowering under one of these natural shelters or better still, crawling right down deep into Udrem itself... In that respect, our destination became attractive.

“Rida,” called a voice, and after a moment’s delay I understood with a stab of surprise that it was my own voice, breaking the silence again. I was calling out to the scientist as I had done some days before. This time I did not need to ask how far we had to go. Now, an immense green carpet stretched less than a mile below us.

That was when I woke completely. In sudden frozen suspense, knowing I was right out of the last of my trances, I watched for the effect of the noise I had made. My companions, who were apt to become almost anonymous to me during trance periods, swam in and out of focus, in and out of name-recognition. My cry had startled the young couple who were holding onto a tangle of stems about five yards to the east along the cliff of the world. Interrupted as they probed for the next foothold downwards, Rida and Cora turned their heads in unison, to stare towards me.

The woman had a drugged look about her, but the man’s gaunt face wore a sharper expression.

“What now?”

What now? His tone sounded to me as though he were fed up with my incessant, nagging chatter. That was hardly fair, since in actual fact none of us had spoken for hours. I felt indignant.

“You said,” I said, “or at any rate one of us said, at some point, some time ago, that when we got close to the jungle, we should, er, form a plan. Now looks like the time!”

He shrugged.

For the first time ever it occurred to me – it was just a fleeting thought – that I might, in some ways, be the equal of this learned and resourceful Rida Sholkov. Certainly he didn’t look too impressive at that moment, his beard at last neglected to become ragged, his eyes sunken (and no mirror was available to inform me that I looked just as bad); how dare he hint that I was a nuisance!

The man spoke: “What is there to plan?”

It was then I realized that his “what now?” had merely voiced the general reproach: what is the point of ANY speech now?

Speech, plans, precautions: how could that stuff be any use at this late stage? Our fate was so clearly imminent; what was left but to sink into acceptance? Easily justifiable, if anaesthesia were the best option: indeed, what awaited us might well best be endured in a sleepwalking state.

However, my snatch of conversation with Rida functioned as an alarm bell. We all paused in our downward climb. Cora glanced sharply at her man and I silently urged her, yeah, go on, rip open the whole cloggy dream. Meanwhile ten yards to the west of me my uncle Vic did his frequent thing of hooking an arm around one branch, resting his chin on another and appearing to brood. Slightly further off, the pale bulk of our decapod pack-beasts, sensing our hesitation as they always did, slowed to a halt.

In my new mood of clarity I was desperate to prolong the pause. We were so close above the jutting mass of vegetation, it seemed an act of madness to continue on down without further debate. I cast about for what to say. If only someone else would succeed where I was failing! I dumbly watched as Cora murmured to Rida and he then reached to help her disentangle some strands of her long black hair from a bush that grew out from the vertical surface of Kroth. I heard a twig snap and her quiet “thank you”. My uncle meanwhile shaded his eyes, lifted his head, and stared, past us, to where the endless equatorial jungle belt disappeared into blue-grey haze. I nodded as he feasted his eyes. Enjoy the view while you can, thought I.

Could anything be done about the mood of silent agreement into which we four had slipped? No, for it was shockingly true that planning was pointless. We were ignorant scouts, mere feelers of Upland civilization, and any plan we might make would be rendered out of date by the first event which caught us inside Udrem.

Therefore our aims must be kept simple. Make a quick plunge into the green mass, peek around, climb back out.

Strong, vivid was that picture – and quite definitely false, because false hope was in command, as my deeper self well knew; dull stupid optimism or sheer stubbornness having taken the wheel while the awful truth waited in the back seat. We were being allowed to act as though we really could get away with a brief dip in and out of Udrem.

*

Slow and careful as ever, supported as ever by the buoyancy ploons attached to our backpacks, we resumed our sinking journey.

The vast excrescence below us grew ever stronger in colour and crisper in outline during the next hour. Blue-grey became green-grey and the grey diminished as the greenness intensified. My eyes forced me to believe that this belt of vegetation really did jut at least a mile from the midriff of the planet. No doubt the outer fringes must droop, as gravity finally defeated the yearning to stretch horizontally towards the sun, but the tangled mass must have terrific tensile strength.

My thoughts buzzed like flies around a carcass called “Duty”. We must stick to our job. Sure, those who had commissioned us were far away. But we must avoid the “out of sight, out of mind” trap. Our people, our cultures, remained real no matter how far away they were. They had put their trust and belief in us. I urged myself: stay true. Repeat the names of the places you know and love. Somewhere thousands of miles above our heads – inwards over the curve of Yeyld, northern hemisphere of Kroth – lay Savaluk, capital of Upland, and the life-giving Fount of Nistoom, and all the other Upland places I had seen, Guthtin my birthplace, Dorington Dradett where the army had taught me to ski, and Neydio where we won the great battle and General Faraliew commissioned us... and in addition to this official trust, all our friends and acquaintances, from Dr Rallod at the Fountain Hospital down to lovable old Mrs Tyler at Guthtin, had faith in us.

Back on Earth, it would have been easier to keep this sort of perspective, for on Earth we had had some global awareness. Superficial though it had been, and tainted by biased news services, the “global village” had nevertheless been enough of a reality to make a difference. But only in very recent times. Such a level of communication had not been typical of mankind’s history, and the far more common state of isolation and ignorance was our present lot as we clung to the side of Kroth. Here was no newsy “wired world”. Here was just a dumb jagged wall that seemed to go straight up and down forever. That was all; that, and our wobbling descent towards the belt of jungle which was wrapped around that ‘wall’.

How misleading, the sheer scale of things. I remembered a fellow called Ugo who had once led me to believe that the Gonomong came from a place called Gonoss. How cute to think of that idea, now that Gonoss was actually way above us. We had passed that particular latitude so long ago that it seemed unreal. Likewise we’d crane our necks in vain trying to spot so many things which we used to think of as far down. Meanwhile the Gonomong in reality still lurked below us, in Udrem from which no legends came.

“People can’t get the big things right,” I grumbled to myself disjointedly… Like that film, One Million Years BC, in which early humans anachronistically battle with dinosaurs. Squash the time-distance to the dinosaurs, pretend it’s vastly shorter than it really is; squash the distance to the Gonomong, like Ugo had done with his inaccuracy... but not any more! I made a wry face: we almost had gone the real distance now. No more squashing of dimensions: we had genuinely ‘done it big’.

*

The next time it was not I who cracked the silence.

Vic it was who called out: “Let us stop here, for a moment, for goodness’ sake.”

We were now a mere half mile above the jutting mass. Sunlight illuminated its green splendour below us. To the limit of vision, east and west, about fifty miles in both directions through the thicker equatorial air, the great jungle stretched to receive us.

Colourful though its surface was, we gave more thought to the dark that must reign below. A foretaste of it was the streaky look which arose from the shadows cast by the ever-shifting horizontal rays of the circling sun. Thus were revealed protuberances in the canopy of vegetation: spikes and twists and billows of green, slow-motion riots in the perpetual battle between plant and plant. The surface stillness was a snapshot of violence. Such power of growth made me wonder why Udrem did not spread to cover the whole world. Could anywhere be safe from such fecundity? But come to think of it the sun’s far greater closeness, here at the equator, doubtless explained why all these competing organisms were intent on the maximum warmth and uninterested in the rest of Kroth.

Vic spoke again: “It’s not too late. Hey! Do you hear me, folks?”

I could not connect with his words.

I was busy with my own discoveries. Even though I had fought in a battle mere months ago, I still had not sorted out my reflexes in the face of danger. I was now realizing, with the jungle soon to swallow me, how rubbish it is to talk of brave men having “better nerves” than cowards. It’s not nerves, it’s the head. Everything that happens, every nerve-signal, is transmitted by the nerves to the head... and the point is, the brave man’s head has different stuff going on inside it. And what is this ingredient of salvation, and how does one obtain it? The answer was coming to me: brave men don’t consider themselves all that important. I could therefore say that it doesn’t matter much what happens to me, so why worry? All right, a crude conclusion, for all human beings are important, we’ve all got souls... and besides, I am on an important mission.

Oh yeah, really? If it’s so important – here came a completely new thought – what about other longitudes? My group of four explorers has made one single transect, has descended the Wayline, longitude zero. The Wayline is culturally important, yes, but after all it’s just one among an infinite number of great circles which explorers might take, and all these other longitudes may have their own enemies lying in wait; I bet the Gonomong aren’t central to everything.

But they’re central to you, chum, said the voice of realism. Also at that moment I noticed something else which put the stopper on all previous speculation. Something which made it unnecessary even to consider what Vic might have meant by “It’s not too late”.

“Uncle, you’re wrong,” I called out.

“Eh?” he called back.

“It is too late.”

The others glanced at me and then looked to where I pointed. They then saw that we had been, as the saying goes, “done”.

Vic said dully, “Oh... oh.”

On all previous occasions when we had halted in our descent, our decapod pack-animals had stopped too, though now that I thought about it I remembered that they had taken a bit longer to respond last time.

This time they had not stopped at all.

“They fooled us, all along.” Vic’s cracked voice drew my glance, and impossibly I saw his chest heave as though he could sob.

Already our pack-beasts had slipped to twenty yards below us. They were increasing their downward speed; we could never catch them.

“All along the line,” agreed Rida huskily, “fooled all along the line.”

“Come back!” cried Cora, and drew breath to shout some more, but wept instead.

The decapods had all our provisions and gear, apart from what we carried personally. I did not have the heart to voice the depths of my dismay, or my sense of betrayal, or the self-contempt that comes to those who have been fooled.

Cora said, “And here’s me thinking all along that we’d done so well, ‘taming’ those things.”

Rida’s comment was: “We were the ones who were tamed.”

“Yes.” A bleak admission from Vic. “Our minds have been tampered with – no doubt about that. Else what are we doing down here?” Then an attempt at a but: “But not tampered with to a decisive extent. Otherwise we’d not know it.”

“Decisively enough, though. They got us down here.”

Nobody gainsaid this. Stupidly we had prolonged our original mission, had extended it and exaggerated it so far as to descend all the way to the Equator.

Rida continued, “We must decide how we react to this fait accompli. Do we play their game? Go on down, try to retrieve our possessions? Or do we turn back and make do with what we’re wearing as we set out to climb all the way back to Topland?”

A pause, while I expected Vic to make some pungent comment. Instead he passed the buck to me.

“Well, Duncan? Rida has summed it up. Play their game or abandon the game – which is it to be?”

I almost laughed in my bitterness. So much for my historic achievement of ‘taming’ Ydrad! All that meshing rapport with the decapod steed – this is what it had led us to – abandonment at latitude zero. And obviously, in retrospect, our epic descent of the world’ flank had only been possible through some influence on our wills.

But then, that’s life. That’s what’s bound to happen, one way or another. Always some tug of influence on the will.

“We can make it our mission. I say we go down.”

*

Inchworms tampering with one’s motivation... definitely not a thought to dwell on. It was good to think of human influences instead, as we commenced our final descent towards the tree-tops. In particular, Elaine Swinton; where was she now? Back home in Topland? Incredible to suppose that I might ever return to see her. Yet need I rule it out as a possibility? And what about the other prisoners? I had rescued some. Could I help the rest? I was well aware of my lack of hero status – but daydreams were helpful to morale.

An odd notion crossed my mind, concerning the rescued Elaine. If I had really loved her, instead of just pitying her, would I have done as well as I did? Love is supposed to be something big and noble, with grand compensations; “better to have loved and lost than never to have loved at all”, et cetera – that’s the theory, but I wondered if I could have given her up, if I had felt about her as I did about the other Elaine – Elaine Dering. Ms Dering was a soul-shaker, whereas poor placidly beautiful Ms Swinton had nothing but her stunning looks, her conformist integrity and dull conversation. She had so little, in fact, that I just didn’t have the heart to let her down, and therefore I did the right thing; I was noble, on that occasion. The emotion of pity – can it be more effective than love? A weird thought.

These mental meanderings were wiped out when a stringy brown mass plunged past me at a distance of only a few yards.

Falling bodies had been a fairly common sight during our descent of the low latitudes, and thanks to The Slant I had just about got used to the idea that they must fall forever unless they whacked into a trung; now, however, it was “back to the drawing board”. For now after all there was a visible floor, namely, the jungle. I looked down at that green floor. I thought about all that could have ever fallen onto it, into it. I felt a real sickness in my gut as I thought of the long epochs of absorbent jungle. All the carcasses that must have plopped – yaargh –

Straightaway an aspect of the Slant came to my rescue; that’s to say, a Slant-honed salvage process went into operation in my head, using one emotion to dampen another. Yes, it said, go on, be disgusted, be usefully disgusted at that green canopy and what it might contain. For as long as you’re preoccupied with disgust you’re not dominated by fear. On the other hand if fear does resurge, then change tack. Call upon one fear to dampen another. Set the fear of letting people down against the fear of the unknown. Or the fear of frightful objects versus the fear of yawning space. Get all fears to compete and lessen one another. Divide and rule. Chop them till they’re tired. Thus reduce them to stale, negligible aches...

“Hey!” cried Cora. “How’s that for a flexy trung!”

She pointed at a reverberating platform four or five yards across. It was the biggest we had seen so far, thrumming up and down like a madly exaggerated diving board. The falling body I’d just seen had hit the trung, had been caught by it.

Good catch, I thought, congratulating the plant: the ‘catch’ had caused some old recycled emotion to surface within me; in an eruption of gladness, I realized how efficient The Slant still was. That successful trung seemed a good omen.

I said out loud – incautiously – “Supposing one of us fell... into one of those things...”

Vic replied, “You’d not survive the shock unless it was a very short fall.”

“Oh.” I wondered how short was short. At what precise point would the physics of it work against us? Perhaps I didn’t really want to know. It was just nice to think of the possibility of a quick cushiony catch.

We all fell silent as we became aware that the jungle’s topmost branches, with their twined creepers and parasitic flowers, now waved tens of yards above us. That meant we were actually descending into the shadows at long last.

Before the sky was entirely blotted out I noticed one condor-sized bird sitting on one of those high sunlit branches, looking askance at me. It cawed once, as if in derision. Then during the next minute or so my head went under the main leaf canopy. Udrem had engulfed me. Almost straightaway I heard a different bird-call, a merrier, well-satisfied Rookoop! Rookoop! The temperature had abruptly dropped a few degrees. It was still warm, but the change made me briefly shiver.

Since the jungle grew horizontally out from the vertical rock face, it was like nothing I had seen before, either for real or in pictures or films. No soil layer could exist at a ninety-degree angle, of course, so the roots had somehow to penetrate the rock, and how they did this, and drew nutriment, I could not imagine; neither was I qualified to judge whether the enormous out-jutting trunks I stepped upon belonged to real trees, or to plants which were merely honorary trees from the ecological niche standpoint as were their equivalents in Earth’s Carboniferous period. I did not question anything; my mind was taken up with the business of choosing a first handhold and foothold amongst the trunks and branches that forked into a multitude of tempting choices on which to trust my weight. They promised me an escape at long last from dependence on the eternal cliff. I reached for that three-D promise. My hand sought one branch, my foot another, and the move was made. From that instant I was no longer a rock-climber but a jungle man. I now had the run of a huge volume of arboreal pathways. These included level stretches (glory be!), roads and ramps and stairs to anywhere in the shaggy gloom.

Rookoop! Rookoop! called another voice from a further branch, and I glimpsed a bird the size of a pelican. Rookoop! Rookoop! it called again, throwing its head back.

My companions – where were they? I looked around, intending to shout out a request that the four of us gather on the broad horizontal trunk I had found. It was time we shared impressions and decided our next move. I thought I glimpsed Cora, further off than I had expected. Then she passed from sight behind a thick branch and a fuzz of leaves.

I filled my lungs for a shout, but hesitated. Bits of colour in motion, amid branches somewhat above me and to the side, made me reluctant to be noisy.

We had seriously underestimated how easy it would be to become separated from one another as we chose slightly different routes to descend. I needed to be active, climb around and find my companions quickly. Unfortunately the ploons, the buoyancy balloons at my back, were not suitable for agile dodgings around dense branchings; I’d get tangled and caught in no time. On the other hand to get rid of the ploons seemed too much of a risk. I would need buoyancy if I lost my footing. What best to do, what best to do?

Next instant, white cottony blobs, on the ends of enlarged quarterstaffs, rose up either side of me. I saw the thick arms that held them, I saw vague numbers of agile shapes; my every thought crumpled into despair and all that was left to me was empty reflex.

Rather than draw my pistol, as the Gonomong leaped onto my branch I reached instead for a smaller dry-looking branch above me, intending to snap it off and use it as a club, but the closest of my enemies whacked my shoulder and as I took the impact of the quarterstaff-blob my hand let go of the upper branch. I still made an effort to square my stance to keep my balance but then I was pushed from behind in the small of the back, and I tottered amidst harsh laughter. The third, the decisive blow, landed on my left side from a Gonomong who swung past me. I lost my footing irretrievably.

Yet my instincts were wiser than my brain: I knew that this was not the end. Killers use lethal weapons, whereas those who want slaves prefer not to damage the goods.

Off the branch and down I fell in slow motion, retarded by my buoyancy ploons, and landed in something that yielded and sagged with my weight. It was a net which must have been stretched with promptness and efficiency; equally prompt and agile, a Gonomong alighted on a surface beside me and wielded a syringe. I was already numb even before it plunged into my shoulder. Events had occurred too fast for my emotions to catch up.

It would have been nice, I thought, if they had held off long enough to give me a chance to get my bearings in this new country, but then a mug is all the more a mug for believing that he deserves any kindness or consideration from destiny… Such self-pitying thoughts lasted but an instant. The final thought before my mind slid into darkness was how amazingly easy it had proved to trap a bunch of fools.

*

From the emptiness in my stomach when I awoke, I knew that hours had passed.

I was confined inside a cube. Not only the floor but the other cushiony, padded inner faces of the cube were within reach of my hand.

Through the one window in this small space, I could see nothing but further soft stuff. It seemed that pillows or cushions were propped up against the frame on the window’s other side.

I say “other side” rather than “outside”, because I felt that no “out” existed anywhere: the nightmare notion had crept into me, that the cell in which I was confined, and the pillows beyond, might be all there was.

All that there was in existence!

The oppressive suspicion that this boxy, pillowy environment was the universe grew steadily stronger, a poisonous swelling of belief. It meant that “escape” was meaningless. Nowhere existed to escape to.

Having lost confidence in the existence of an outside, I could only expect to find more enclosure, a reality stuffed with smothering pillows, forever. In which case, what would be the use of even thinking of trying to get ‘out’? A settled deprivation rooted itself in my soul. Amazing as it sounds, within a minute or so this dreary belief had dried every hope into its parched woe. Dusty, hopeless finality.

I possessed my clothes and nothing else; my backpack was gone; altogether, I was nobody and nowhere and nothing – and this was because, basically, there was nothing…

I could write reams about that dreary time, but of course it would be impossible to chronicle such a state. If such an account were to succeed, if my narrative really did convey what the experience was like, no one could bear to read it; besides, it wouldn’t be morally acceptable to recall the experience fully. Even if I had the skill I would refrain from any effective depiction of that cosmic smallness, that suffocating universality, for success would mean that I would then be doing to the reader what the Gonomong masters did to me. That is, I’d shape into seeming truth the desolate idea that the All is not much. And that would amount to the crime of brainwashing. Moreover, retribution would (I suspect) quickly follow. Not sure how, but while writing this account, as I look back from a long way off, I’d be prepared to bet that if I were to recapture the memory in full, it would reach out a claw to recapture me.

My recollection does not extend to the practical details. For example, how the place was lit and ventilated, how long I was there, whether I was fed and how – these questions I cannot answer. On the other hand no explanation is needed as to why I made no serious attempt to escape. I hardly even thought of it - which shows how peculiarly different this was from normal imprisonment. We normally imagine a prisoner to be someone who is denied access to freedom, a freedom which lies beyond the confines of his cell, but here, as I have tried to convey, since the very notion of “beyond” ceased to credible, not only I but reality itself appeared confined, and so nothing existed for me to escape to except possibly some more cushions, pillows, padding and windows which might open upon other cells or passages that would let me worm my way through yet more universally cramped hopelessness.

Imagine, now, that you have read a further hundred pages in this vein… and having taken them as read, we can proceed to when the scene unzipped.

*

Without warning, the walls of my cube sagged and bowed and crumpled. The pillowy “beyond” became two-dimensional. It, likewise, crumpled. The entire boxy environment was torn away and discarded.

I found myself, after all, in a real outside.

My body tingled, my mind glowed and I was inundated with a vast happiness.

I was standing on a fat branch, Udrem all around me, which of course did mean enclosure of a kind, the sky being hidden by boles and shadowy leaves, but in comparison with the soul-stifling from which I had just emerged it was a paradise of openness.

Fabrics from the disassembled cube-and-pillow universe lay strewn around me. That sad nightmare was over.

Overwhelmingly grateful for my deliverance, I began my life of ‘normal’ servitude.

I can vouch for the Gonomong method of conditioning a slave: it is masterly.

*

My owner, a hulking “Unspior” (as they want us to call them), stood about four yards away, bow-legged with his feet planted across the width of the branch, his gorilla-like arms dangling. His head was slightly larger than that of a human man; his face heavy in the jaw, Mussolini-like, crudely handsome. The ugly thing about him was that he embodied untouchable and irresponsible power. He spoke a word I did not understand. Immediately a wizened old “normal” human came forward from behind him and halted between him and me.

The Gonomong growled a sentence, and the old slave interpreted:

“For the avoidance of doubt you must now say ‘yes’ to confirm that you are fully awake, alert and ready to listen to instruction.” The man added, “I would advise you not to dissemble. Say ‘yes’.”

“Yes.”

Evidently the Gonomong knew what “yes” meant, for he grunted as if he had expected no less, then gave vent to another sentence in his tongue full of oongs and ungs.

“Unspior Maragoom directs me to tell you for the first and only time, what

the penalty for disobedience will be. Please say, ‘yes, I am listening’.”

“Yes, I am listening.”

“The Drop. Repeat that, and for goodness’ sake stop staring at your master.”

“The Drop.”

I stood with head bowed as I said those two words. Nevertheless my disobedient eyeballs rolled up. I peeked at Unspior Maragoom. Then, flick, a down-jerk of the eyeballs because I didn’t want to be sentenced to The Drop or, worse, give cause to be sent back to the pillow universe. At all costs I must avoid that. I felt the shakes coming on...

But the master was turning away, satisfied.

My limbs loosened in relief and I took a step forward and opened my mouth to question the old slave.

He jabbed out a hand in a gesture that froze me. Then at a sudden release from weight the branch lifted under our feet – the master had jumped away. “Now,” muttered the oldster to me, “now you can move. You will have to improve your manners, you know.”

“Uh?”

“Unspior Maragoom was lenient on this occasion. He usually tolerates the first lapse of etiquette by a new slave. I recommend, however, that you do not try his patience again. Or mine, for that matter. I am Dreaker Choik Maragoom,” he continued in a fuller voice, “and you will address me as Dreaker.”

“Yes, Dreaker.”

“The title means ‘interpreter’. You will probably never learn the language of the Unspiors, and it is even less likely that any of them whom you meet will have learnt English (though I have, on rare occasion, been privileged to converse in English with a few of the learned masters)...”

I was happy to listen to him brag on. In my state of timid euphoria I felt no resentment or indignation at his fondness for his own status as a prize chattel of the Gonomong aristocracy. Still full of relief at my emergence from the ‘pillow-universe’ delusion, I was anxious above all for just one thing: that I never run the slightest risk of being sent back there. This meant that I was mainly concerned that everyone around me should remain in a good mood.

“And now, to work,” announced Dreaker Choik. “Until further notice your occupation will be to remove wastes and take them to the Throwers. I shall supervise you on your first round. Follow me and don’t try to give me the slip – assuredly, if you do, you’ll get lost, and any lost slave is assumed to be a fugitive slave, hence ripe for The Drop.”

The wiry oldster then jumped off the branch. I did the same, mildly surprised at my own steadiness, finding my footing upon the branch below. Part of the credit must be due to long training by The Slant, which largely suppresses vertigo. Also there is the fact that Udrem is so dense that if you lose your balance you can almost always retrieve it by grabbing at a growth of one sort or another – a branch, a long fibrous leaf, the stem of a tough creeper. And it is impossible to fall far (unless of course you are at the edge of the domain). All this was just as well, since my buoyancy ploons were gone.

Our route led us down sloping branches formed into a sequence of ramps, the steeper ones with crafted hand-rails, deeper and deeper into the interior. The gloom intensified; but after a few minutes I saw strings of lights.

The first time I was led past one particular stretch of these, I saw that each light was an orange sphere the size of a Halloween pumpkin though it glowed not with a candle but with bioluminescence. As well as those strung along the larger arterial branches that served as roads, other glowing spheres adorned dwellings, arboreal mansions in an endless variety of shapes and sizes which were woven and trained and moulded from wood, creepers, pods and topiary, singly or in combination, scattered like Christmas tree lights in this three-dimensional realm.

I would have dawdled in wonder, but Dreaker Choik told me to smarten my pace. “For your own sake,” he grumbled over his shoulder, “remember you are visible from all sides.” And indeed the scanty light played on moving patches and dots visible to me through random gaps in the foliage: Gonomong near and far, swinging or striding above and below and to the sides of me. Dreaker warned that eye-contact was a deadly offence, so I tried to make sure that I never looked straight at any one of them.

Presently he halted below one of the dwellings.

“Fetch that,” he said. He was pointing at a bulge that dangled beneath a flimsy outhouse. “Use its straps, put it on your back. That’s right...yes,” he added as I wrinkled my nose at the squishy sacking, “you’re on lavatory waste-removal duty. Somebody has to do it. Now for the next house along. You’ll do six of them on this trip.”

By the time I had collected my sixth load I was glad he had set that limit in advance; it reduced my tension to know that he did not intend me to break my back. Not, of course, that it made economic sense to misuse a slave. In fact, so I told myself, I was worth something as property and surely this set-up wasn’t so stupid as to risk the health of a good chattel...

“Next stop: the Throwers. Get a move on or you’ll not finish before the relief shift. That wouldn’t look good on your record or mine.”

I carried the malodorous bags for maybe a quarter of an hour along an arterial sequence of branches, following the Dreaker right through the horizontal thickness of Udrem... or so I guessed, as the dwellings petered out and the branch-ways we trod grew thinner. More and more frequently I noted supporting creepers fixed taut as the cables of a suspension bridge, while ahead of me the leafscape grew paler, and with a thrill I began to glimpse patches of clear blue. Yes, we were almost all the way through.

A type of object loomed ahead, new to me, square and dark. Soon we came up to it: the house-sized back end of a polished wooden frame, lying on a broad matting about half as big as a football pitch. A crew of eight slaves stood idly by. Dreaker told me to dump my burden on the loading platform, I did so and the “Throwers” leapt into action, shifting the bags into position, but I scarcely noticed what they did; I was feasting my eyes on what stirred me most, the great patch of glorious blue emptiness visible in the catapult’s line of fire.

“Don’t stand there gawping,” said Dreaker, so I had to turn my back on the sky and go fetch the next consignment of ordure.

On my next arrival, with another six sacks, Dreaker allowed me a longer rest and I was able not only to glimpse the sky again but to watch the firing. Swish, the sewage shot into the blue; the dots fell away, dwindling, passing out of sight below the visible patch of blue, to fall forever through the universe – unless of course they happened to land upon some unfortunate world directly beneath ours...

Waste disposal, I reflected, must be even easier in the lower, more southern parts of Udrem. In the districts adjacent to the under-edge, from where one could see the sky below, you wouldn’t need a catapult. You’d have The Drop.

Dreaker Choik supervised me on all of my first day’s rounds. He carefully monitored every aspect of my performance, caustically reminding me what would happen if I made a mess of the job. I obliged him, I was a good slave, and in return I was inducted into my new life. The slave quarters, where I lunched and supped and slept, consisted of a pod-like complex of trained growths. My own pod I found quite sufficiently comfortable for my diminished expectations. I was as yet far from being crushed by the true horror of my position. My dream-conditioning was still strong. It ensured in me that grateful acquiescence, that meek obedience which was vital for survival; otherwise, I might well have blundered irretrievably; I might have bothered Dreaker Choik with inquiries concerning my companions, within hearing of a master, with fatal results.

The daily routine was dull, heavy work which did not quite wear me out. I was fed well enough, I was housed satisfactorily (together with a dozen other slaves whose wits were as slack as mine), and the shameful truth was that life was bearable.

My excuse is, that so long as memories of the pillow nightmare persisted vividly in me, I could not help but continue to be ruled by servile gratitude for my release from that claustrophobic state, and with my mental sails thus trimmed, I drew all my spiritual and material sustenance from the little pleasures of my existence: free air, adequate food, rest after work, the occasional sight of sky.

I did possess a tinge of awareness that such gratitude must have limits, that eventually it must cede to humiliation and discontent and resentment at my lot. Time, in this sense, worked in my favour, but in another sense it worked against me, insofar as each day taught me further to adapt to life as a slave.

Of course you must adapt in order to live, but, as I have noted before, in doing so you get moulded, betrayed by your own survival skills until you have adapted so far that the original “you” is dead. New Hampshire’s motto “Live Free Or Die” is quite realistic – the real “me” was headed for a death that would leave the husk, the slave “me”, just as the authorities wanted.

However, they made one mistake.

*

I had just swigged my morning juice at the entrance to my pod, and was about to wash the cup and tidy away my breakfast bowl, when the branch thrummed to that degree which signalled visitors. I hastened outside.

Dreaker Choik had dropped his weight onto the branch, but he was not the sole arrival. The hulk behind him was one of the masters. It was a safe bet that this meant trouble. I hoped the Unspior would stay well back so that we might more easily avert our eyes from him, as etiquette demanded.

“Assemble!” cried Dreaker.

I walked forward onto the front platform of the complex. So did my fellow slaves, and I glanced at the shambling figures with the same distaste I felt for myself whenever I suffered a moment of reflection.

I had not made friends with any of them. They were mere husks of personality, fixated upon getting through the day. In short, they were as hopeless and uninteresting as I. If one of them were about to be condemned to The Drop, I would be sorry, in a numb sort of way, but my feelings would hardly be stirred to their depths.

“Listen carefully, men. Unspior Saomalaf has honoured us all with a request for a volunteer...” and here Dreaker paused to allow us to absorb the full impact of the master’s generosity, “for special service. The Unspior directs me to make it clear, that he does not wish his time to be wasted, as it might be if he were to pick a slave who turned out to be a coward. So on this occasion he is leaving it to one of you to step forward: one who is not afraid to enter the Oracle Caverns. So then! Which of you is more than a sewage worker?”

This was a lot to absorb. Nobody made a move.

“Come on! Whittnash? Petrides? Dakin? Wemyss? Sangster? Any of you ready to measure up to this opportunity?”

I saw that none of the others were about to stir. I guessed they weren’t likely to. The seconds ticked past and my nerves drew tight at the thought that the Unspior might be in for a disappointment. How a Gonomong might react to such loss of face was something I certainly did not wish to find out. Nobody would dare to point out to him that a person who asks for volunteers ought to be able to face the possibility that he will not get any. You don’t ‘point things out’ to an Unspior; you don’t bandy arguments with him in any way. Gonomong require prompt obedience to the letter and the spirit of their wishes and commands, no hitches or complications, no excuses, no nonsense and no cleverness. So now comes the funny bit –

Like the build-up to a sneeze, a comic little train of gasping thoughts, ah – ah – ah – because I was a coward – knowing that one of us had better volunteer – for all our sakes – and I didn’t trust my fellow slaves to see this – didn’t trust them to be as scared as I was – didn’t trust them to fear what might happen if the Unspior felt spurned – I wet my lips – and choo! – out sneezed the decision, “I volunteer”.

“Come forward, Wemyss. Bow to the Master.”

Now that I had taken the plunge I wondered whether, if only I had held out a few moments longer, one of the others might have come to the same conclusion and saved me from having to be the one. Oh, well. I bowed. The promise of a break in routine must have done it. It had disturbed my equilibrium, opened a fault line in the crust of habit and allowed a spark of spirit to rise. How silly of the authorities. They ought to have allowed me to stagnate. As it was, while my body bent in the bow I found myself thinking, “this is my disguise, I am pretending to be a docile slave.”

Thrum. Unspior Saomalaf had left the branch.

Dreaker Choik beckoned, and set off in the direction which must lead through the thickness of the forest towards the vertical face of the world.

I obeyed the command to follow, and as I walked beside him he spoke out of the corner of his mouth, “If you fail, the punishment is terrible, but in your place I should have made the same commitment.”

In a similarly low voice I ventured to ask, “What are the Oracle Caverns?”

I more than half expected to be told off for my curiosity, but all I got was a shake of the head and the disclaimer, “I cannot say anything useful to prepare you.” We hurried on, along branches and horizontal trunks which grew generally thicker until within minutes the solid body of the planet became visible ahead, a wall which was revealed in patches of dark grey.

I dared to open my mouth once more: “What caused the vacancy?” – but silence stretched between us.

We came in sight of Gonomong sentries on platforms, on either side of an archway. It was formed by a mass of twisted boles which crept like obese ivy over an oval area of the vertical world-wall, while a particularly thick cross-branch did duty as a threshold. Through the arch gaped a blackness.

I stared ahead in a keen search for any light that might relieve that dark, and I did discern some tiny reddish pillars like inflamed tonsils; one of these was briefly eclipsed by a silhouette passing in front. I suddenly sensed how far in I could see, and began to apprehend the scale of the Oracle Caverns.

“A long time ago,” murmured Dreaker Choik, “I used to be like you. I used to ask questions. But it doesn’t do. Walk forward now, and don’t stop till you’re told. Goodbye, Wemyss.”

*

The Gonomong sentries, if that’s what they were, did not question me as I stepped past – did not even glance at me, as far as I could tell.

My eyes strained to adapt to the sudden dark, while my boots, after so many days of walking on wood, trod at long last upon stone. I smelt a damp mixture of scents – putrid mould, or springy moss? Bracing or disgusting? I forced myself on.

Continuing through a widening entrance passage, I faintly glimpsed some clutter at first – what looked like piles of lumber and up-ended boards – but then space expanded around me dramatically, the wall on my right retreated into the gloom, I was in the cavern proper and I sensed it was huge.

I wondered whether I dared stop to get my bearings. Would even a momentary hesitation earn a reprimand by some watcher? I continued, while noting that on my left, thirty feet up on the cavern wall ran a row of dozens of luminous clocks, their prismatic faces tilted like down-staring eyes. Further in, a reddish light was thrown across the floor from an irregularly spaced series of incandescent pillars that glowed from top to base. A useless pang of memory came to me, of the normal lamp-posts in my home town on non-existent Earth. These pillars here must be the “tonsils” I had seen from outside.

A woman’s voice, calling me “Hey there”, made me stop at last, and turn. I saw a gaunt figure rising to her feet from a crouching position. Pale pink in the cavern glow, she staggered like a drunken ghost while her stringy hair dangled askew, but she regained her balance and said “Sorry, bit stiff... Take this.”

The slave woman had been working next to a large wicker basket. She held out to me an object that looked approximately like a trowel. I took it from her. When she reached for a bucket and handed that to me too, I breathed a sigh of mingled relief and disappointment. Back to work, and the luxury of boredom...

“Over there,” she pointed. “You’re to scrape the mould off those roots.”

I went up to the side of the cavern and saw what she meant: at a low level, a yard or so from the floor, the rock wall was lined with hairy roots, thick as drainpipes. In fact, as I heard a faint gurgling, I wondered if they actually were pipes.

“Like this,” and she showed me what to do.

The mould I was supposed to scrape off – a sickly green encrustation – was faintly phosphorescent. I heaved a sigh and started. The green stuff came off in little shavings with which I slowly filled the bucket.

“Look busy,” she advised. “We’ll talk later.”

As my eyes got more used to the dimness, I wielded the scraper faster and more efficiently; my surplus energy and frustration welcomed an outlet, and for a while I attacked the job energetically. Later, my hard work became less of an unthinking snarl and more of a considered policy: it might, I hoped, win me some privileges from the masters. My greatest wish was to increase my freedom of movement. That would gain me hope. Some day...

I turned at the sound of footsteps. It was the slave woman again. She was carrying a pannier of food; she held it out to me with both hands and I could tell the effort tired her. I saw her more clearly than I had before. Her face was lined and yet not old; I guessed her to be about forty, a used-up, exploited forty.

“Meal break,” she announced. “My, you’ve done well.”

Her faded looks saddened me. Wanly appealing, aglow with innocence and goodness, she inspired me like a starting gun, to set out on a race for freedom. I must take the plunge, and to begin with I must dare to trust the right people. Which meant I must get better at taking risks. To go on as before, to play safe and be grateful for small mercies or even for the one big mercy of having been let out of the pillow universe, would get me nowhere.

“Thank you,” I said to her; “I appreciate your kindness very much indeed, er...”

“My name is Ada Tholl.”

“I’m Duncan Wemyss. I’ll eat with you, if I may.”

“It will be nice if we ate together,” she said placidly. “Let’s go join Clem.”

Clement Harr turned out to be a slave just a few years older than I, scraping roots along the opposite cavern wall. We traversed about a hundred paces to get to him. The three of us squatted and lolled with our lunches. With his knees drawn up and his heavy jaws munching, Clem looked like a pleasantly thick footballer at a break during practice. However, when he spoke, I got a rather different impression.

“Heard it again,” he remarked to Ada. “That gurgle.”

“In the same root?” she asked.

A nod. “The Mongees’ll be talking to Naos again.” His words made no sense to me, but his disrespectful tone did. That was what was important to me just then. I said to myself: never mind what he’s talking about – has his conditioning worn off?

“Hush,” said Ada primly. “As we hope for Shoo Guneeng Gheeng, we should not begrudge the masters their own hope of immortality.”

“Courtesy of the Slimes.”

Ada twisted her fingers. “Not fair – so much supposition –”

“A lot of it is,” Clem agreed, “but not that. They’re in touch with something down there.”

I hardly knew how to play it. Getting the right balance – keeping my ears open for useful facts, prompting for more when possible, but not pushing it disastrously – was hard for me. Yet, finally, I got my mouth open and asked:

“Something down where?”

Clem turned to me and spoke one word: “Hudgung.” Then he must have seen the look on my face for he added, “Sorry, you’re new here, I was forgetting. Not a nice thought, is it?”

Kroth’s scarcely imaginable southern hemisphere, Hudgung was the underneath of the world. An utterly fantastic topsy-turvy realm, ground overhead and sky below... My thoughts prickled in goose-bumps which were not totally unpleasant so long as the horror remained picturesque, mythical, removed from everyday reality.

I licked dry lips and said, “You serious? The masters – in touch with Hudgung?”

Clem nodded. “What else can explain the Mongees...”

Ada whispered, “Don’t keep calling them that!”

“All right, Ada, for your sake I’ll refer to them as our noble masters the Gonomong.”

“Don’t even say that! They’re the Unspiors!”

“Sure, anything you like. Er – where was I? Oh yes: what else can explain the way the Unspiors carry on? Their bouts of rage against the north, their stupid invasions, when really they wouldn’t want to live up there even if they did manage to conquer the place? For surely, if they tried to settle permanently in any other land than this, they’d miss their jungle...”

Ada meanwhile kept glancing around. Obviously keen not to prolong this discussion, she refrained from comment after Clem finished his speech.

I, however, wanted to hear more.

“What else than what?” I asked him.

“Eh?”

“You were saying, what else can explain the Unspiors’ behaviour, and then you talked about the behaviour. What else than what can explain it?”

“What else than the influence of the Slimes?”

Ada gasped.

“Come on,” I said impatiently, “you know I’m in the dark as to what this is all about.”

“The Slimes of Naos,” muttered Clem, lowering his voice at last, “at the South Pole.”

In a flat voice I said, “I don’t know what you mean, I don’t know what they are.”

“Who does? And what does it matter what they are? Their aim is to conquer by proxy. They can’t go north themselves, thank goodness. They can slither all under Hudgung, but they would find it physically impossible to get past Udrem.”

I said in an eager murmur, “This is all very interesting, very interesting indeed, but you know, Clem, even more interesting is to hear your tone, to hear any such tone of defiance in the voice of a slave. If we all –” I stopped.

Clem Harr’s entire body-language expressed retreat. He had dropped his gaze and his posture slumped. I, more easily influenced than I liked to admit, drew back from my line of persuasion with that sudden and ridiculous double-take of a cartoon character who has run too far along a branch that is about to break.

Ada Tholl turned to me with that sickly smile that goes with a shake of the head and an award of zero marks.

“The sort of remark you were about to make,” she said, “is better not said.”

I most carefully reassured her, “I accept what you say, and I shall be grateful for any further instruction from you.”

“You seem to need it more than most,” she remarked.

“Ah but, you see, I am new here.”

“And you will never grow old here.”

Chilled by this, I yet chose the stout reply: “I should hope not. I didn’t suppose I was volunteering for a lifetime task.”

“No living slave is ever released from here. Your days are numbered, along with ours.”

“I don’t accept that.”

“But be comforted,” she went on, “that afterwards comes Shoo Guneeng Gheeng.”

“Shoo Guneeng Gheeng,” I echoed, intrigued by the new shine in her eyes.

“Shoo Guneeng Gheeng,” she averred.

“I never heard that name before.”

“It is the land of horizons, plenty, beauty and peace.”

I did not think it wise to reply: Ah, yes, Topland – I do know the place, for I have come down from there. A slave religion based on distorted geographical knowledge? Too hot a topic for me to handle just then. I strove to control my expression, to look neutral, blank, calm.

“You smile,” she said in response to my facial twitch, “but really, seriously, it should be enough for us all. Shoo Guneeng Gheeng is our all-sufficient hope – though Clem, being Clem, must grumble and snort his way through the days which remain to him.”

That “night” – that sleep period in the perpetual dimness – was bad. Hours ticked by, while I thrashed about in my slave-nook, plagued by the bitter irony of what I had just learned – that legends of Topland had evolved into these folk’s Heaven; that in this sense I had voluntarily departed “heaven”, had voluntarily exchanged it for this hole.

The best you could say about the Oracle Caverns was that they were lit (albeit dimly), ventilated, watered and provided with sanitation. You could live there without too much discomfort, until you died of despair. I no longer wondered what had happened to the man I had volunteered to replace. I caught myself muttering you incredible idiot, why did you volunteer?

I fought back at the encircling barbs of self-reproach: I refused to tolerate the notion that I had made my final mistake. “Sometimes you have to gamble,” I retorted, “and maybe this game isn’t yet lost. I am not dead yet. I am not yet even convinced that this cavern is any worse than the rest of Udrem.”

So – no recriminations.

Nevertheless it was as well to bear in mind from now on, that I could not afford a single further mistake. Dreaker Choik had impressed upon me that no trained slave ever annoyed the masters twice, and although I had previously fought openly in battle against the Gonomong, it would be fatal for me to fall into the illusion that I had the status of a POW. Here, if your escape attempt failed, you didn’t get sent to Colditz; here, you were for The Drop.

I was physically tired after my first “day” in the cavern, yet sleep was slow in coming. Through the entrance to my nook I glimpsed occasional dull orange lights bobbing past, borne by Gonomong padding about their unknown business, while one of the occasional glowing pillars, just out of my sight as I lay, threw a faint pink fuzz on the opposite cavern wall. In this reign of silence the one sensation which disturbed me as I slowly got drowsier was the smell. My various cleaning jobs had taken me about a furlong into the cavern’s depths, where, during the “day”, I had already taken note of unclassifiable smells which seemed to blend into one another without visible cause, as though carried by shifting air currents, but nothing about this had bothered me at first, for the ventilation was good, the air, I presumed, moving through a whole sequence of galleries within the planet, of which this particular cavern was the outermost. In a way it did me good to feel that I was close to contact with the unknown, since the unknown gives promise of change, and change means hope. But those smells were really peculiar. Had I been less tired and more alert I might have worried more. As it was, I finally slipped into an undulating dream in which the latest odd whiffs were merged with hammer-headed swimming shapes that bumped my skull... but they did not quite manage to crack my head open.

*

In my life on Earth I had been quite fond of watching old Star Trek repeats, and there was one episode in particular which stuck in my mind: the one entitled “Mirror, Mirror”.

It nicely typifies the way Captain Kirk lives by his wits. His instinct for survival can work in a split second to make him react as though he has figured out what’s happening, even though he’s had no time at all in which to do so.

In that particular episode, a magnetic storm interferes with the operation of his ship’s transporter beam, and he materializes in an alternate universe. (At the same moment the alternative-universe Kirk finds himself in our universe. The magnetic storm has swapped them round.)

Our displaced Kirk can’t possibly know, in that bewildering moment, that he has been beamed up to an alternate version of his ship, in another cosmos, in which ship and crew belong to a fascist / imperialist type culture that rules by violence and fear: but when he sees his crew greet him with a strange style of salute, he salutes back in the same way. How’s that for instinctive reflex! At some basic level he has instantaneously grasped that he must not let his astonishment show.

I did not know it when I awoke, but the new day was about to produce a not entirely dissimilar test for me.

Nothing to do with alternate universes. But a moment did arrive, at breakfast, when my nerve might have cracked, when I was confronted with my equivalent of Kirk’s ordeal, the same threat of stupefaction, the face of apparently insane reality – that which must not be, but is.

Four of us were sitting cross-legged by the provisions basket. We formed a square, with Ada Tholl and Clem Harr adjacent corners, while I and a new slave girl who introduced herself as Jane Hodder were the other two corners. Jane was about my age; a sweet, shy, dreamy lass with a gentle voice and buck teeth.

“Well, the food’s good, anyhow,” Ada remarked, biting into a celery-like coating stuffed with meat (the “sandwich” of Udrem). Something in her tone made me stare at her. Was this the contented Ada of yesterday? The Ada who was happy to wait for an afterlife in Shoo Guneeng Gheeng?

And then she went on to add:

“Opium of the people.” (Munch.) “Keeps us docile.”

I doubted my ears. Ada had said this?

Clem replied, “What of it? Just because we’re slaves, doesn’t mean we shouldn’t appreciate the good things of life that come our way. The food is good – so enjoy it.”

Ada then did something which disturbed me further. She spat.

Continuing out of character, she grumbled, “Fodder and swill. That’s its function, however good it tastes.”

Clem shook his head calmly. “Now, now, Ada, be reasonable. You know what really keeps us quiet.”

“Yeah? What do you want me to say keeps us quiet? Our hope of Shoo Guneeng Gheeng?”

“The eyes in the clocks,” shrugged Clem tiredly. “It’s as simple as that, as you well know. We’re constantly watched, and as soon as we make trouble, we’re for the Drop.” He then leaned forward and spoke intently, “But as for Shoo Guneeng Gheeng - that is no opium dream. It’s our compensation, for real. Once we’ve passed on, we shall have the last laugh there.”

It was Clem who said this. Clem who – the reverse from yesterday – now upheld the reality of Heaven while Ada, formerly contented, grumbled cynically.

The two seemed to have swapped personalities.

This was my Kirk moment. Less cosmically drastic perhaps than the universe-jump in “Mirror, Mirror”, it was nonetheless a near-paralysing horror. By rights, one person can convert another but they do not swap. If they do, if reality suddenly gibbers, it’s as bad as if the cat barked.

Luckily at that moment an emergency supply of guts was airlifted into me from some unknown dimension, giving me the presence of mind to keep quiet and still, and to adjust my response downwards to a “wait and see”.

I might otherwise have run away in horror, to be promptly arrested and condemned as a nuisance. Or even if I had panicked quietly, the awfulness, the smell I had whiffed last night, the whatever-it-was that sought a way into me, might there and then have curled out of the roots of the Cave to grip me via my weakened brain.

The moment of being appalled – that’s when, like Captain Kirk, you must retain the mien which glides you over the worst seconds, and that is what I managed to do, and when the evasive glide had succeeded I became aware, as a kind of reward, that Jane had given the conversation a new and different turn.

She was speaking in a tone of hero-worship; her eyes shone with ecstasy:

“His Highness Prince Rapannaf is shortly to pay a visit to these Caverns.”

“Cor,” sneered Ada.

“He shall be close to us! We shall see him! And who knows, he may even get to speak to one of us!”

“Bully for him,” scoffed Ada.

Eyes brimming, Jane went on with the proclamation of the joyful news which the “grapevine” of slave rumour had brought to her. I listened in pity as she expressed her naïve dream of a reform-minded Prince, who (so the rumour ran) was on the side of the slaves, and would set them free when he achieved power in Udrem.

Pathetic though it sounded, it did at least complete my picture of the way things worked. Her words and mood had shown me a pattern, and now that I understood the main lines of it, I told myself that my nastiest moments were over, and I could face the peril in cold blood.

While at my labours during the remainder of that morning, as I scrubbed and scraped, I had ample time to contemplate the set-up.

It was a sophisticated system of control, vastly more subtle than the lash of an overseer. The wafting smells triggered day-to-day fluctuation in the slaves’ beliefs. These beliefs functioned as a series of valves to relieve psychological pressures which would otherwise cause break-down. Such a system, beyond the capacity of any totalitarian regime on Earth, was child’s play, no doubt, to the expert forces who controlled our lives in Udrem, whether those forces were the Gonomong them-selves or the “Slimes” which Clem Harr referred to the previous day.

After all – the various beliefs were not actually contradictory (I realized this more and more as time went on). Cynical grumblers did not actually disbelieve in Shoo Guneeng Gheeng, or in the motives of the Prince. Anything might be true in a sense. It was just a different way of letting off steam, a different fad for every day.

Odd how I seemed immune....

I supposed that I must be an incorrigible ideological misfit. An oddball – as you might expect from someone who had kept the full vividness of his Earth-dream memories.

Maybe, given time, I would conform – maybe the control process simply had not had time to work with me yet. And whether it eventually did or not, I could not see how I might ever pose a threat to the authorities.

I did wonder, though, if they had miscalculated in one respect –

I heard during the next few days from chats with slaves who, in turn, heard it from a human overseer called Dreaker Foraker, that Prince Rapannaf really was due to visit the Caverns at some point soon.

It had to be true: the overseers would never dare spread any lying rumour which concerned one of the Masters. The fellow was on the way to us.

But surely the authorities would be daft to produce a real Prince. If they intended to continue to drug their workforce with this saviour-Prince myth, the last thing they should do was to allow such an inevitably disillusioning visit to take place. It didn’t make sense!

If only I had Uncle Vic to discuss it all with… and that got me wondering for the umpteenth time what had happened to Vic and Cora and Rida... It was no good, all I had was myself, my own thoughts, the conundrums and mysteries which were my only true companions.

Perhaps – here was a cunning notion – I did not really want to solve the mysteries, for then what would I have left? Dimness, work, eventual madness, death.

The smells which kept the others stuffed with hopes weren’t working on me. No “opiate of the people” soothed me. I guess my brain might as well have been labelled “wash-resistant” ever since my stepfather’s violence, way back on Earth, had turned me into one of those strange people who do their own thinking.

On and on, “day” after “day” I worked in the dimness, while at “night” I smelled the weave of hopes which tried and failed to enmesh my mind. During meals I heard the grumbles of my companions and their hopeful talk about Prince Rapannaf and their yearnings for Shoo Guneeng Gheeng, and upon me grew the fear that sooner or later I would run amok.

I began to ask myself crazy questions such as: if I were to assassinate the Prince, what would the authorities then do to sustain their myth?

You fool, I thought: kill the Prince and you’ll be for the Drop and what good will that do? They’ll just think of some other ideological scam. Besides, have you forgotten what killing means? All right, all right, but you see, Duncan old bean, I’m afraid of the desert of lonely time, and I need some distraction in this dark. My fellow slaves aren’t any real good. Arrogant though it sounds, I do seem to need some higher class “opium” than the type that satisfies them. You keep harping on that, don’t you, Duncan? Yes, whichever way you look at it, I admit I’m fed up. Start off like Marx, saying religion is the opium of the people, or turn it round and say that very same thing about political panaceas – nothing really works. It’s all deception. Society depends upon deception. Very profound, Duncan. What you really mean is, you landed yourself in the soup.

I was poor company as I chatted to myself during those dim days. The sensible thing would have been to cultivate the friendship of my fellow-sufferers, a decent bunch who would have given me the comfort of companionship, yet I could not yet bring myself to do this because, the way my mind worked at that time, to associate more closely with the other slaves would have been tantamount to admitting that I was doomed to remain one of them.

*

One ‘day’, I asked Ada, “Where’s Clem? I haven’t seen him for a while.”

She did not look me in the eye. “The Drop,” she muttered.

“What?” As time went by I had begun to imagine The Drop as something remote; now the notion again jumped terrifyingly close.

A hand touched my sleeve. I turned, bowing sickly over the pit of my stomach. It was Jane who was pulling me; Jane steering my attention away from Ada.

“She doesn’t want to talk about it, Duncan. What happened was, Clem was lazy at his work. A couple of days in a row, he was late and inefficient. He said he was going to reform, but he had already been warned by Dreaker Foraker...”

My stomach still squelchy, I made a supreme effort to blank out the nauseous vision that came to mind.

We were all especially kind to Ada Tholl that “day”.

*

It was one of those breakfasts at which some of us had to abandon our food sooner than others. One of the Dreakers had appeared, had handed the latest schedules around, and it appeared that Ada, with two others, Sabina and Randall (I remember the names, crystal clear along with countless other details of that morning) were due to work much further down the cavern. So they left early. Jane and I alone remained, squatting by the food basket.

“This is handy,” I said, just to make conversation. “The rota favours us. A few minutes’ extra free time to relax...”

Jane’s mouth was open wide. Her lips stretched, jerky as an old movie. I stared, wondering: was she about to bawl? The Dreaker had muttered something in her ear just before he left. I hoped she wasn’t in bad with the masters.

“Maybe more,” she replied.

I realized I had got it wrong – what I was seeing on her face was a smile of excitement.

“More than a few minutes, you say? But –” Any form of casual disobedience seemed far too risky under present circumstances. No way would I incur the same penalty as Clem Harr. No way would I risk being late.

“You will not have to hurry this morning,” smiled Jane.

“What is all this – Oh,” I answered myself. “The Prince, of course.”

She nodded, “The Prince. He will be here soon.”

“Jane,” I said gently, “how can you possibly know?”

“Dreaker Bayles is one of us.”

Bayles was the one who had brought us the new rota. Dreakers had contacts outside the Caverns, and if this Dreaker was “one of us” he must be part of the pathetic conspiracy of hope centred upon belief in a reforming Prince, a Good Gonomong, an enlightened sort who was about to come and liberate the slaves. All at once I envisaged my future laid out clear. I looked to the result of the Prince’s visit – disillusion; or of his failure to appear – heartbreak. Either way, I must console Jane. And this would be the saving of me. I needed to be needed.

“Here he comes,” she whispered reverently.

>> 6: Revolt