the forgetters

a tale of the osmium era

from Uranian Gleams

by Robert gibsoN

1: Escape

He was sunny in temper and placid in manner, like a good-natured, overgrown boy; she, by contrast, was not “sunny” at all. She was a live wire that hummed with passion and impatience.

Both were young, handsome, rich… Taldis Norkoten and his wife Athness Keprella lived in an expensive quarter of Vyanth, the largest, most splendid city of Syoom.

Vyanth could boast nigh on a thousand palaces during the Osmium Era, and the home of Taldis and Athness was one of these opulent mansions: a pedestalled globe linked by walkways to other costly structures above, below and to the sides. Taldis Norkoten employed a considerable staff to maintain his home. Usually one or more of these servants was in view, discreetly busy at tasks of cleaning, polishing, repairing, catering… but right now they had all made themselves scarce: not one of them dared to begin to clear the table at the end of this particular mid-day meal; they retreated as Athness unleashed her fury on her husband.

“I am sick and tired of your excuses,” the black-silked goddess flashed at Taldis (and he squeezed his eyes shut as he usually did when his senses had been blasted by her scornful beauty). Acidly she continued, “It’s not as though we even needed the wretched salary they pay you; yet you insist on spending half your time risking your life for THEM. And to cap all of that,” she almost choked, “you refuse to do your share of the house-admin this afternoon because you have a meeting – a SIC meeting!”

“But wait,” he pleaded, “you already knew, you’ve known for a long time, that I’m an S.I.C….”

“Spy.”

“A field operative for the Syoomean Intelligence Corps.”

“Im-pressive,” she intoned. “How lucky can a girl get!”

“Loyalty is loyalty,” he persisted, “I take it as I should. The interruptions are part of the job.”

Athness now squeezed her eyes shut. “Oh you goody-good being,” she sighed, realizing, not for the first time, that this was the root of the trouble between them: there was something too-good-to-be-true about Taldis. Despite having the sordid job of “spy”, he was morally untouched by the cynicism which pervaded the SIC. Rather, he acted like some character dreamed up by simple-minded thriller-writers who routinely portrayed Intelligence Corps agents as heroes forever foiling Quonian agents’ dastardly plots to subvert civilization. And though all this was far too much to swallow, you could not touch Taldis about it at all – he was not even priggish; you couldn’t fault him in that or in any other way. So, detached as it was from the seamy side of real life, his stance was impossible to believe in but also impossible to smash – he was impenetrably good. Something, no doubt, was going on inside that curly head; but what?

“Go on,” Ashness shrugged tiredly, “go to your meeting.”

“So I shall,” Taldis said. He rose from his chair. She was silently waving him away.

Knowing that he might well be gazing upon her for the last time, he spoke against his better judgement:

“Why didn’t you tell me, Athness, before we were married, that you weren’t in sympathy with my work?”

“Why didn’t you tell me,” she retorted, “that you didn’t know what the word ‘marriage’ means?”

“I know what it means,” he said quietly, turning to go.

“Then you should know it means putting me first.”

“Ah, but perhaps I am.”

She grinned at that. “You mean, by saving Syoom from the evil Quonians? Sparing me their nefarious attentions? Thanks for the rescue,” she said sweetly. Seeing that he did not turn round or rise to the bait in any way – he was just walking off – she let out one final hiss of exasperation. She called after him the insult which no decent Syoomean every used in public. “You’re such a foregrounder, Taldis!”

That word – he must not hear it, must not react to it. He ignored it. No matter that foregrounder hurt like a wallop in the guts. There was nothing he could do – except wonder what had happened to the lovely woman he had married twelve hundred days ago.

To admit that things might be partly his own fault would merely invite another blast, on the lines of, “Why don’t you do something about it, then?” And he did not wish her to know that this afternoon he was going to do something about it.

So he merely shook his head as if to dislodge the nightmare of mutual incomprehension which his marriage had become. He could not afford to have it preying on his mind during his meeting with Director Woth.

The oval outer door swished open at the touch of a button. On the instant that he emerged from the mansion, the cityscape of Vyanth gripped his attention. It gave him the needed tonic to his morale. Taldis’ inner strength came largely from his capacity never to take anything for granted; this is the general virtue of his species – the Nenns, Uranian humanity, are masters of context-awareness. He, however, had it to an exceptional degree. Though he had gazed upon the cityscape thousands of times, he was still as freshly struck by the wonder of it all, as if he had just arrived from another planet. The irregular lattice of globular palaces and walkways, like a model of some complex organic molecule, lanced and inter-threaded by the helical towers and pierced by the polyhedra which housed the economic and record-keeping functions of any great Uranian city – all were vibrant with colour and movement, as skimmers raced along the ways, and laden hover-rafts floated up and down. But there was more to it. The 3-D effect drew Taldis forth from himself; made his consciousness expand…

Spurning the use of skimmers, rafts or escalators, Taldis Norkoten tramped along a pedestrian walkway which sloped upwards into the sparser, loftier regions of the geometric urban forest.

SIC headquarters appeared as a discreet thickening of the branches of this “forest”. The thickening in that region was caused by a larger than usual number of jutting or dangling rooms. They gleamed with new paint: the relocation of Headquarters from Skyyon to Vyanth had been quite recent.

After crossing the lobby, where a brief identifier ray tingled against his flesh, Taldis took the lift to the fourth floor where a pretty receptionist (trained to kill if necessary) waved him through the door beyond her desk.

It was not a good sign that there was so little paperwork on the much larger desk which he now faced. Director Woth was known for clearing the polished top before inviting someone in to be fired. On the other hand, it wasn’t quite empty: there was one file lying on it.

Deep-set eyes brooded under the slope of Woth’s gleaming forehead as Taldis advanced. “You haven’t been doing too well, T-N,” remarked the Director, giving the lone file a shove. “Is that why you drew up this proposal?”

“It is, sir.” In more ways than one. He saw no reason to detail all his motives. The mission plan was valid in its own terms, or so he hoped.

“Sit down, T-N.”

To be seated opposite that bony lean head, that face with its jutting sickle of a nose, was to feel pinned by the Director’s will, even if the man’s glance was pointed elsewhere. And when the glance became direct… then, even the toughest agents were apt to become subservient or, worse, self-justifyingly garrulous. Taldis, however, possessed a kind of somnambulistic calm. He had escaped from his miserable home; he had entered the consoling zone of work.

“This is the very first time,” Woth was saying, fixing Taldis with his most ruthless glare, “that one of my agents has suggested hiring the services of the Vemorth Stazel.”

The Society of Forgetters. The way he said it, it sounded ridiculous.

Woth continued after a ringing pause, “You realize, don’t you, that the Forgetters are used nowadays merely by clients with business or engineering problems, who require nothing more than a dose of partial amnesia to get a fresh, unbiased look at a particular problem?”

“Or,” said Taldis, “to protect their secrets by locking then away in the subconscious for a period.”

Woth waved the comment aside. “That point is immaterial. You realize that the kind of ‘global forgetting’ you’re suggesting is a much more rarely-used technique?”

“I know, sir, but the Stazel themselves have admitted to me that the, uh, global option is still available to one who cares to use it.”

“Hmmph.”

And from the tone of that snort, Taldis knew that he had won his point.

Woth crooked a smirk, “It’s typical of your rather quaint approach that you present a plan which, as far as I can see, involves no spillage of enemy blood. No assassinations, no frame-ups. I rather like it. I must be getting soft, like you.”

“Somehow I doubt that, sir.” Taldis risked a smile of incredulity. After all, Woth was always telling him that a civilization engaged in a perpetual cold war with a ruthless adversary will inevitably descend to the moral level of its foes, at least as far as secret operations were concerned, and that nothing could be done about it.

“Well,” proceeded the Director, “though your idea lacks kick, it’s certainly sly enough. I dare say that if we don’t try it, some day the Quonians will. You know it has always bothered me, the way we persistently underestimate them. Your idea amounts to a neat little move which we can make to forestall them in a minor way, at no risk to our organization, while at the same time giving you, T-N, an opportunity to restore some of your credit with us. None too soon, either. During the past couple of hundred days you have been allowing your personal problems to interfere with your professional competence. Fair comment?”

Athness would not agree. She would say it’s the other way round.

“Fair comment, yes, sir.”

Woth smiled the cold smile which was the highest temperature he allowed himself. “You’re an unusual agent, T-N. I hope you continue to be as unpredictable to the enemy as you are to your own side. Be off with you now. I’ve sent on your authorisation ahead of you; you’ll find it when you report to the Vemorth Stazel.”

The Society of Forgetters will remember me.

Taldis said, “Thank you, sir,” and meant it. Not bad, he thought elatedly as he strode out of the building. It was no common achievement to get away from old Chisel-Face with the feeling that one had got what one wanted.

The next step was to deposit a farewell cube in a transmission booth… He did not reproach himself for this seeming callousness. Just leaving a message might seem cruel, but he was in the right. To maximise his chances of survival, he must preserve his effectiveness and that meant, for a start, avoiding another reproachful good-bye. Ordeals like that were worse for the nerves than any mission into enemy territory. After all, Athness’ complaint was that he kept risking his life, Well, then, he’d look after himself! Click – in the message went. Now he was free.

2: To Skyyon

One of his skimmers, ready-packed, would be his home for the day it took to fly at top speed to the sunward polar city.

He owned several of the craft; they were scattered in various banks throughout the city so that, wherever he happened to be, it was never far to walk to the nearest one. He preferred to walk as far as possible but when a skimmer was necessary it became a joy to him. As he slid it from its storage bay, affectionately he ran his palm along the hull of recycled metal, imagining contact with previous incarnations of that metal, probably other skimmers ridden by other adventurers, ridden into the ubiquitous pool of adventure that was the meaning of life on this giant planet.

He would not lose sight of his own particular mission and its current importance, or the fact that he was acting under orders, yet he mounted the saddle with the satisfied sureness of one who has leisure and freedom to wander where he wills, for it was easy to pretend, in such open-ended moments, that he was his own boss. Moreover, he might in truth become so; life’s paths could lead pretence to veer towards fact.

He switched on the motor, opened the throttle, gripped the steerstick, floated forth from the bank and swept into a glide – the perspectives of the city shifting around him like the boughs and fronds of a polyhedral jungle. Down the skimway he swept to disc level. Having reached this floor he wove his way till he struck a radial avenue, which led him directly to the rim: the city’s clear peripheral oalm free of buildings, smooth as a ring around a gas-giant planet. Here the tug of the ayash current gripped his vehicle and lifted it high. Over the edge and out of the city and down onto the plain, where the airstream dropped him and he was on his own.

Now no longer carried by the air but tearing through it, he was skimming just six yards above the plain. He put up the cowl before gunning the motor and increasing speed to the craft’s limit of two hundred miles per hour. Only once did he glance back at the receding splendour of Vyanth. The view was sustenance for the soul: the giant tray piled high with lights and held aloft by a stem, the stem dropping away towards the rear horizon. What nobler work could there be, than to defend that?

Yes, spy though he was, he need feel no shame: his job was the most worthwhile expenditure of a man’s life. Nothing mattered more than to help preserve the accumulated cultural riches of seventy-six eras. The sordid word “spy” meant, in his case, maintaining brilliance, guarding what brought warmth to the cold of a giant world. So he was free, after all, for he was doing what he chose to do.

Thus the city of Vyanth, disappearing from sight like a fond parent who wisely allows latitude to nen’s children (a city ought to be ‘nen’, not ‘it’, nen had personality), received love and loyalty in return. I have survived unconquered, said its metropolitan voice, through ten thousand human lifetimes. I am always there for you, citizen Taldis Norkoten. I stand constant, wherever you are.

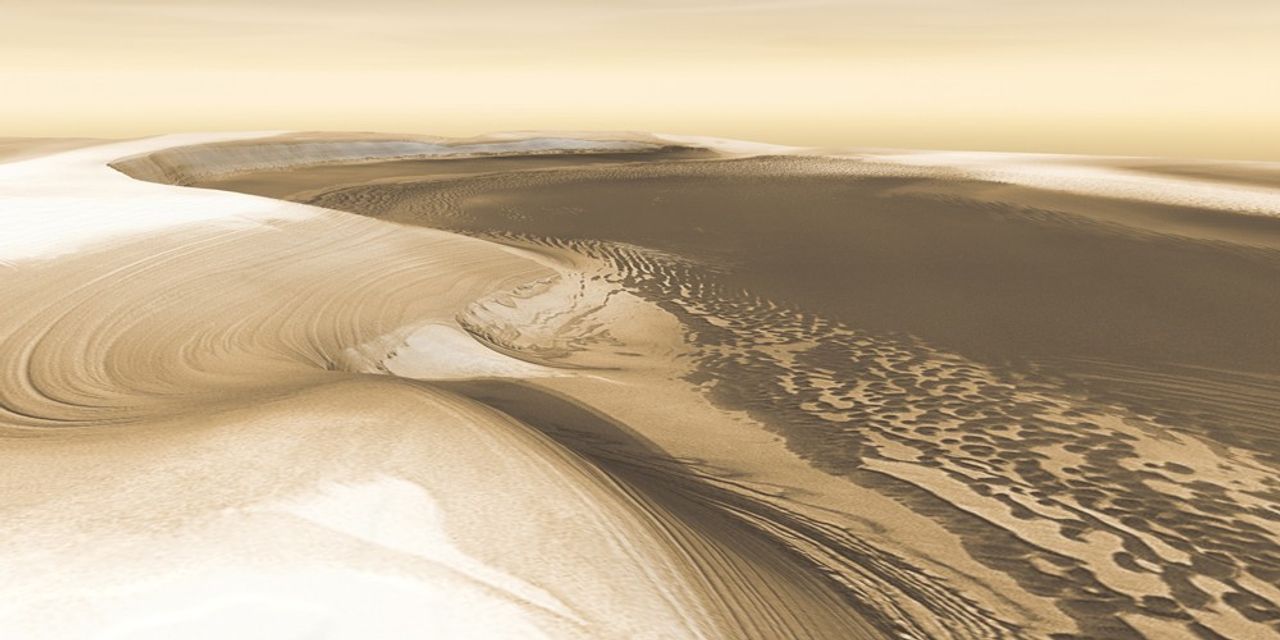

In fact for the first twenty minutes or so Taldis had not yet left the ambit of Vyanth. The light from glowing fields of vheic provided an outer halo to the city’s brilliance. But after that, as he bulleted past the last farms he experienced a new, firmer grip of infinity. The giant world had him in its hand, drew him out of his urban home. The strong fingers of that global hand were the liver-coloured plain, the vault of sky and the remote, encircling horizon. Always, round about this point, Taldis adopted a suitably nomadic mood. The mothering warmth of the city gave way to the “coolth” of the plains.

A skimmer’s top stable altitude is six yards. Storm-riding techniques can make it go higher, but here there was no storm. So – six yards. Yet in this emptiness, as far as appearance was concerned, he could have been travelling at two thousand miles per hour sixty yards above ground, or just twenty miles per hour at only twenty inches’ altitude. The absence of scale and his steady speed nudged him into a dreamy state of mind.

Every so often, scale returned at the sight of objects such as a lone hive-tree, a hill, a grove, a farming settlement or a flapping bird. They helped to keep him awake, but as they streamed past they accentuated the loneliness and the vastness. He knew that if this sensation ever became too much for him his mind might suffer the condition known as nebulation, wherein one’s consciousness roves like a cloud and can no longer attend to human-sized concerns. A nebulated man can even forget his own name.

He wasn’t worried that it would happen to him. Confident in his experience as a wayfarer, he was an old hand at checking his mental wanderings if they showed signs of an ominous tug. Anyhow, this particular stretch of wilderness was unusually friendly to Man. No hour went by without sight of a silver ovoid floating on patrol in the upper air. That frequent presence of airships was the basis of the Great Triangle, the special area bounded by the cities of Ao, Skyyon and Vyanth, each about six thousand miles from the other two. Each power trusted the others, in close alliance, to contribute resources for patrol of the area between them. Originally aimed at deterring piracy, the arrangement had evolved over lifetimes into a ‘weeding’ service whereby, in these fifteen million square miles, all kinds of trouble were prevented from taking deep root. And if the word “Syoom” (“Civilization”) is used in its literal sense to mean “the area in which a lone wayfarer can travel a thousand miles with a fifty-or-greater per cent chance of survival”, the Great Triangle provided its inhabitants with a super-Syoom where the value was better than ninety-nine per cent. The fact that Taldis’ journey to Skyyon was turning out so uneventful was yet one more tribute to the Triangle’s everyday success.

He must cover six thousand miles at two thousand miles per hour: that made thirty hours, exactly one Uranian day, of journey time. When evenshine dimmed to anyne, he set the autopilot alarm to warn him of obstacles or topographic change; then he unfolded the deck-couch, erected the side-guard to prevent him from rolling off in his sleep, and lay enjoying pmetn, the brief evening treat of a sight of the stars. Only during the atmosphere’s transparent stage, between night and day, could the stars shine through it to share the sky with their polar chief, the faint and distant sun.

The air darkened further, towards the opaque blackness of yyne, the blanket which hid not only the stars but also the sun. Presently, Taldis Norkoten slept. He woke in time to see the stars again: in refelc, their appearance at the end of pallyne, before they were obliterated by the brightening air of morningshine. More hours passed. The light grew further, into ayshine, the brightest time, the middle five-hour section of day. Skyyon’s topmost spire should be appearing any time now. There – a flicker?

The plains were bright.

The plains were dim.

Taldis rubbed his eyes. What exactly was this? A real flicker, or was it in his mind?

The plains, he understood, were bright due to eye-adaptation. Uranian humanity, native to this world, must be accustomed to viewing it in its own light and to seeing that light as adequate.

Yet simultaneously the plains were dim. In some real, objective sense they possessed that quality of faintness.

For one weird freezing moment Taldis endured the blink between bright and dim, bright and dim – then he relaxed as his imagination righted itself.

More clearly than ever before he knew that he had chosen the correct path; that he was a natural for the Vemorth Stazel, the Society of Forgetters.

At that very instant a swelling star appeared on the forward horizon, a star that was no star but his first glimpse of the flame-shaped Zairm, the Palace of the Noad of Skyyon, its tip now revealed at a distance of two hundred miles.

3: At Skyyon

From the journal of Taldis Norkoten:

11,544,672 Os:

I awoke with a burnt smell teasing my nostrils. Opening my eyes, I saw that I lay in a high-ceilinged, narrow room. My bed was up against one wall. Along the other three walls ran a long table interrupted at one point by a door. On the wall above the foot of my bed hung a poster.

I focused my eyes on the message on that poster. It said – in big blue letters, in my own handwriting –

YOU HAVE LOST YOUR MEMORY

BUT THAT DOESN’T MEAN YOU HAVE LOST YOUR MIND

I swung my legs to sit up and, as if that had been a signal, the door opened, sphincter-like. A woman stepped through. She stood hands on hips, surveying me. She wore trousers and blouse. It – the blouse – would have provided good camouflage in a field of garish wild-flowers. Ah, so I did still know what flowers were. The woman, who was maybe twice my age, had red hair and grey skin which puckered as she smiled. She gloated a bit.

“Confused?” she asked.

“Haven’t got that far yet,” I replied grumpily.

Indeed it was more a matter of stuff in my head wanting to rear up and make trouble. “Why are you looking at me like that?” I demanded. “Am I a difficult patient?” I was verging on being scared.

She nodded, “Showing spirit, I see. I am Diren Ev, Director of the Vemorth Stazel. And you are a customer named Taldis Norkoten, of Vyanth.”

“Customer?”

“Literally, yes. You asked for what you’ve got. And we gave it to you, oh yes we did.”

Her voice had grown vibrant, celebrating her professional joy. I cut in, “I need a friend, or at least an informative enemy. I have plenty of ideas of what might exist around me, but what I know amounts to nothing much.”

Without taking her eyes off me the woman sat on the edge of the table. She stretched her left arm and switched on a viewer.

A rapid flow of clipped scenes showed me standing in a lobby being welcomed, shaking hands with Diren Ev and others, being guided into an office, getting sucked into a whirlpool of inductions and demonstrations: sign this consent form, take your cloak off, sit there, put your head back there…

“Never,” remarked Diren, “had I met such confidence in a client, such utter lack of hesitation.” She switched off the screen, stood up and moved closer to me. In a voice that grated towards hoarseness, she said: “In fact you’re quite a foregrounder, aren’t you, Taldis?”

Her tone was suddenly transformed, hostility had surfaced, and the word foregrounder put me on my mettle. Which goes to show how one can suspect an insult without knowing a thing about the circumstances.

I replied, “If that’s something bad, I take it you are a backgrounder.”

I wanted her to realize that despite the wiping of my personal memory I could still recognize resentment when I heard it. For if I didn’t stand up for myself I might never learn where I stood.

Diren’s cheeks quivered. “I suppose I deserved that; ‘backgrounder’, ha yes, that’s what I am all right, just one of life’s extras, off the spot-lit track. A bit-part at most... If I were to go off into the blue, the way you plan to, I’d pay. Heavily.”

Something in her eyes caused me to back-pedal: “Let’s not have any further mention of foregrounder and backgrounder… I get the feeling they aren’t polite terms. In fact, I suspect they’re tabu.”

Her face cleared and in a sunnier tone she declared:

“Good, your social residue is intact!”

“I’m sorry, I don’t understand.”

She was all briskness now. “That was my little test. Regrettably, I had to use bad language.”

“Test.” I dumbly repeated.

“Naturally you don’t understand – you’re not meant to; just take it from me at this stage.”

“Take what?”

“That the most efficient way to check that our delicate operations are successful, is to administer a little shock to the patient’s sense of propriety.”

“And so the social thing –”

“Social residue. What you can’t do without. What we had to make sure you retained. To remove personal memories, while preserving social aptitude, is not easy. Since you are our first fully-dosed client for quite a while, I am particularly relieved at this evidence of our success. In short, my lad, you are house-trained. You can safely be let loose.”

I thought about it and decided she was right. I felt blank, but not bewildered. In fact I had an oddly secure feeling within me, as though I had found the firmest path through life.

She handed me my cloak, my belt and my laser, plus a palm-sized electronic guide to the city (designed and written for children), and a notebook of instructions which I had apparently written to myself. In this last she drew my attention to the date and time and place of my next rendezvous. “Think of it! Off on a mission! How grand to be a spy, working for Director Woth! Meanwhile, come back to me if you need any help before you leave Skyyon,” she added, “though I don’t suppose you will.”

Risking a snub, I asked: “Shall I let you know how I get on?”

“The news will reach me, never fear.”

I bid goodbye to her enigmatic face, went out of the room and out of the building, and lounged by the porch, where the first thing I noticed as I gazed around the cityscape was the absence of sharp shadows. Definite shadows had been thrown indoors, caused by lamps and ceiling lights, but it was different out in the hazy urban jungle. The illumination did vary, but fuzzily. For example under the bulge of yonder great pod-like structure the light might be somewhat dimmer than elsewhere, but the differences were gradual... smoothly leading the eye into a blur of infinity.

I fingered the lining of my cloak, and the clips to which telescope and pouch were attached. Then exploring the contents of my pouch I touched triangular coins and felt their rounded vertices: this must be “money”, and immediately (part of my “social residue” as Diren would say) I knew what “money” was. Next the metal laser tube at my belt, and the leather texture of my boots, taught me whole aspects of life: fighting, stock-raising, the life of the plains under a city’s protective power. My wrist transceiver was of less interest because for the time being I could not think of anyone to call.

Now to leaf through my notebook… Much of what I’d written meant little as yet, apart from the details of my next rendezvous and the password I must use. Doubtless the rest of it would come in useful later on. The main thing right then was that I felt self-sufficient. Simply via sight and touch I could sense that the culture I was in had evolved through thousands of lifetimes towards allowing a man to go his own way. In a pleasant mood I stuffed the notebook back into my pocket, and I started strolling forward over the metal city floor.

The dumpy, squashed-loaf building I had just left, soon obscured by intervening stems of raised structures and skimmways, had been unimpressive; other agency buildings which I soon found myself walking past cut better figures: Departments of Cloud-Talkers, Orographers, Naturalists, Gralmers, Historians…

The city-guide which Diren had given me asserted, “Skyyon is the nerve-centre of Syoom.” I could well believe it. In fact one could picture the escalators and skimways as nerves. And the suspended buildings which they linked, body-organs…

I overheard snatches of conversation from the people walking and skimming about me. I could distinguish three languages spoken, all of which I understood although only one of them was my native tongue. As the city-guide said, “Skyyon is the cosmopolitan centre of Syoom, the inevitable site for the Sunnoad’s Palace…”

I button-paged further through the guide, in order to read about the Sunnoad.

“…the Noad of Noads, the focus of foci. Ever since the remote past, the Sunnoad has led the allied cities of Syoom whenever danger threatens from Fyaym. The Sunnoad has to be the most lremd person in the world…”

More button-pressing to check I knew what LREMD meant – but in vain. Nowhere was the word explained. Apparently, everyone, even every child, is supposed to know – so perhaps I must know, too.

Same for the dirty words foregrounder and backgrounder. I must already know them without yet knowing how to access the knowledge within me.

But as I write these words their meaning hits me at last: the two terms denote the two kinds of people: those who serve as main characters in a real-life story, and those who only form part of the supporting cast.

No wonder the words are offensive when spoken. Were such a distinction to become explicit, it must risk an explosion of envy. So it must all remain secret, dirty, suppressed. The rule is, don’t even hint of them out loud, lest the issue blow society apart. Diren Ev did dare to offload her resentment, but only in the presence of newly blanked old me.

In fact maybe I had better rip out this page of my diary.

No – on second thoughts I had better not rip it out. A report is a report. My boss, Director Woth, can stand the obscenity if anyone can.

11,544,673 Os:

…I managed to find myself a hotel. It’s a globular palace high above the lower floor of Skyyon and close to the “roof” of the upper floor. I didn’t have any trouble checking in. It seems that I can talk to people safely enough, in an ordinary, business-like context. Apart from that, though, I have refrained from socialising. A friendly chat might easily lead me to giving away my status as a Forgetter, and I don’t know what view people might take of a dis-minded person wandering around loose. Diren Ev knows I am harmless but others might not. I want to stay out of trouble till the rendezvous; and it isn’t anyone else’s business what I am, anyway.

Lunch in the restaurant – crusty meats and fruits, cereal loaves, and a tall glass of fiery viscous liquid – put me in good form for spending an afternoon exploring the city. The next day, I did more of the same. I indulged my curiosity to the full. Let me admit it for the record – I am enjoying myself.

Most of Skyyon is exuberantly jungle-like with mansions sprouting like fruits at the ends of tubular ways, but a few districts at floor level are different – restrained in style. These dignified areas are built of imported stone, forming pavements and staid terraces of houses which immediately overlie the metal floor. In my view (and I’m after all supposed to record my impressions, no matter how silly they may seem) these low-key stone terraces require explanation. A rival dream appears to have inserted itself into our architectural heritage. Full of this idea, I ventured into the Institute of Urban Design, gave Worth’s name as a referee and asked the opinion of one of their experts. Nothing in our species’ past, he agreed, can explain the style of the stone terraces. I then put it to him, that we may be under the prescient pull of some future trend. Then, having scattered this little seed of speculation, I left. I gather that this is the way I am supposed to behave. This is why I have had my memory erased by the Vemorth Stazel. I hope the result will be useful to somebody. Meanwhile, I confess it, I have been having fun.

I have continued to saunter around, looking into what pleases me while I await the rendezvous. My basic social orientation, my “residue”, gives me a sense of security while my clean-slate mind makes all things fresh and new, without (so far) being alarming. Like a holidaymaker I went and hired a skimmer, and was fascinated to learn (from an amused attendant) that the basic design of these vehicles has remained unchanged since they were developed way back in the Neon Era.

My condition makes me able to look at the two seats – the high rearward saddle and the lower hollowed-out seat “amidships” – as though I had never seen them before. Likewise objectively I studied the storage compartments, the fuel-phials compressed from phosphorescent vheic-plants, the motor, the buoyancy tanks… To anyone who saw me I must have seemed like an overgrown child, gawping, poking, fiddling… well, Woth, you asked for it. You told me to note everything. But don’t worry, I understand that there’s a bigger picture.

You hope that as a newly blanked outsider-mentality I shall spot some vital thing to give us an edge over the Quonians.

Well, I shan’t get anywhere by trying too hard. No use straining…

It occurred to me, Woth, that you might want me to delve in the great library, so I went to have a look. I found myself able to use the film-records easily enough. This was time well spent insofar as it proved I was able to understand technical instructions for the use of systems, but I couldn’t see the point of staying there long; my emptied brain is meant to “travel light”…

11,544,674 Os:

I have extended my range.

To reach Skyyon’s upper floor, you first proceed to the outer rim of the lower floor. There, you find fountains of skimmers riding the airstreams in two directions: the main one, out of the city and down to the plain, and a lesser stream, upwards and inwards. That second one takes you to the top city tier, half the diameter of the first, and half a mile higher.

That’s where I am now, writing this on a park bench in sight of the Zairm, the Sunnoad’s Palace. The crowds up here are sparser. The atmosphere is more sedate. Over this rarefied district hangs the smell of power.

Skyyon, so my pocket guide makes clear, does not rule the other cities. Each disk-on-stem metropolis is independent of the others. Yet Skyyon is in an important sense the capital of Syoom. The Sunnoad, the Noad of Noads, the focus of foci, has nen’s residence here. Goodness knows what qualities one must possess to hold down that job.

Lremd, no doubt, whatever that is.

As for formal rights and privileges, I am told they are few. By immemorial consent, the Sunnoad takes command when general danger threatens Syoom from Fyaym. To rebel against this authority is almost unheard-of. To obey, or even to be noticed by the Noad of Noads, is such an honour that there is no need of compulsion. When the Sunnoad speaks to you, history comes fully alive, and you know what it is to live; that’s what many have said. I sometimes crane my neck towards the summit of the Zairm and wonder if he is looking out of one of the windows. What must it be like to be such a person, imprisoned in such fame? How must it be to know that one’s every action will be judged in the pitiless glare of history?

11,544,676 Os:

I saw more open sky, as I climbed further into the thinned regions and upper sectors of the city, eventually reaching the airship docks. This gave me a view of the navy suspended at its moorings, the skyships like globular clusters in a galactic halo. Along an aerial walkway I went up close to one of the docks at a moment when one of the ships was gliding in. The ovoid hull, fifty yards long, swelled in view as it slowly turned to reveal the name Knorol painted on its side. It decelerated till it nudged the platform with feather-light precision.

The door cycled open and the crew began to disembark. Scores of men strode jauntily towards the freedom of a few days’ leave at the end of their patrol. Meanwhile in the other direction I saw the replacement crew. They had been standing further back than I, for their numbers would have got in the way of the disembarkation, but now they all pushed forward. I retreated, to back against the walkway railing. It would have been a long fall from there to the city floor a mile below!

“Interested in my ship?” sounded a voice to the left of me. I turned to see a burly man in a cerulean cloak, trim beard and loam-brown eyes. He had planted himself in the midst of the walkway.

I asked, “You are Captain Choad?”

“Yes, and you are Taldis Reperzint.”

It was as if a light-bulb had flicked on in my head, and I knew what to reply:

“Not today, sir. Today I am plain Taldis Norkoten.”

“Just so.” This rigmarole over, the captain gestured towards the entrance to Knorol. “Come aboard. Your Director has told me all about you.”

I followed him inside, and in the company of some other officers we threaded the grey corridors. The glow of the ceiling-strips guided us like arrows to the carpeted cavern which was the control room. Here I was invited to take a seat, while the crew prepared for departure.

My rendezvous had been successful.

4: To Quonia

When the floor trembled under my boots I stood up, eager as a child, and full of gratitude as the captain beckoned to me with the words, “Come and watch.” I hurried over to stare through the glass “port” (actually one of the rear viewscreens) at the view of Skyyon as we receded from the dock.

Choad joined me a couple of minutes later at the screen. “A perfect departure, right on schedule. Indirectly, you are to thank.”

I turned to him in surprise.

He nodded, explaining:

“My group has been waiting to charter this ship for scores of days. It might easily have taken longer still, without prompts from your boss. Welcome to the Survey Service.”

I had been mildly curious as to how the Survey had come to co-operate with Woth. “I suppose,” I shrugged, “you and Intelligence are natural allies.”

The captain glanced round the control room and said, “Time for a drink in my cabin, I reckon.”

When we got there he gave me a tall glass full of orange liquor and said, “Take it slowly. It’s Grardesh – strong stuff. If you know what getting drunk means…?”

His face wore a facetious look, and I suspected he was holding back some amusing conclusion. To play safe I remained literal: I took his question seriously and thought about it. Drunkenness… it did have a vague significance to me. “Something to do with a substance in fermented juice imbibed to excess,” I replied, and added, “I doubt whether I could ever talk about it from personal experience.”

“No need to sound so prim.” He sat back and twirled his own glass, definitely amused. “Do you know where you’re going? What you’re doing? What you’re discovering? No? Never mind… A special providence looks out for drunks and Forgetters.”

11,544,681 Os:

Choad’s friendliness springs from the interest I hold for him as an experiment. He is a devotee of an obscure science called ‘psychology’. This motivates him to study how my blank-state mind reacts to data; and I don’t object, since it gives me the run of the ship.

Yes, it’s lucky for me, the way things have turned out. The Survey Service has few ships of its own, so it needs to charter others. The pure-science philosophy of men like Choad is, I gather, out of step with today’s priorities. So they take what they can get, in alliance with the military, and Choad doesn’t seem to resent the link; instead he compliments me, tongue in cheek, on my “valuable objectivity”. I think he thinks Woth’s ideas are a huge laugh.

But maybe contrasts are misleading. To me, at any rate, the Survey Service doesn’t seem to be noticeably less tough than the military. Though the crew of Knorol are scientists first and foremost, I get the strong impression that they could put up a fight if they had to. And the foamed ore of Knorol’s hull could take quite a few hits – I can judge for myself the strength of the ship as I roam around it, observing its cellular structure and all the redundancies built into it.

I applied to join the official observers’ rota and they paired me up with a plains-watcher named Tarpik, a bulky fellow with a mournful face and sleepy eyes, who muttered a greeting and then turned back to his scanscope. We took turns with it for many hours, session after session, to monitor the ground flowing past beneath the ship’s keel. The task can get monotonous, but it’s dreamy and narcotic rather than boring. You stare and stare at the surface a mile below, and you jot down your subjective impressions which are believed to be of some use in addition to the records of the automatic cameras. Sometimes there’s more. I remember one occasion, when, just as I was beginning to get lulled by the dazzling blur, a carpet of blue marching spikes began to cross my field of view. No need for me to give a full description of the sight; the Director of SIC can demand to view Survey Ship data any time he likes. My point is, it seemed that none of my shipmates seemed to know or even care what the spikes actually were. Not even when they began to fire upwards at our ship. I felt the floor lurch under me as we rose higher to avoid the projectiles. No other action was taken, no attempt made to alter course to follow the things after they had crossed our path. I was tempted to remark that I was not the only empty-brained person on board. How could the personnel of a research ship be so lacking in curiosity?

But all I said to Tarpik was, “Why don’t we at least see if we can find out where they live?”

“Got to keep to our sample-line,” he replied. “Preserve comparability with the previous transect. Else the entire voyage is wasted.”

I muttered, “Scientific method, eh?”

He said nothing; he went back to his work.

I have no real complaint. Maybe they’re right.

[Later.] The captain has increased our altitude to two miles. In addition to my stints on the scanscope I make observations of my own through my cabin window and the screens in the control room, where I’m allowed so long as I keep quiet. As in some wavy dream the colours of the plains meander continuously beneath us, while occasional wrinkles, mounds and saw-edged ridges that have heaved up through the surface pass us by. More rarely, we fly over larger humps, which are said to be the tips of mascons convected through the ice-mantle of Ooranye. Such frozen disturbances are often accompanied by clefts, chasms, gorges. Elsewhere, patches of life dot the desolation: lonely hive-trees, spiky groves, splotches of grassland, even the odd zone of human settlement. But what predominates is always the plain. Endless, like space itself, it shares the view with the sky. That brings me to mention the… clouds, one calls them, flocks of them, which throng and squirm in increasing numbers, around the ship and sometimes below it.

More and more it is the clouds which provoke me as I stare from my cabin port. The nebular phylum, so I am warned, becomes denser in the hinterlands of Syoom, and dominates the skies of Fyaym. I watch veils and ropes of cloud, hunting or fighting each other, even at times flinging themselves against our hull so that we sense a thud through the floor plates.

To me, as a Forgetter, it is a fantastic panorama. It’s so full of unrepeated sights, that I find it hard to believe that any bits of knowledge we acquire will amount to anything more than a few scrawls in the corner of a blank sheet of paper the size of the world. Come to think of it, I suppose you don’t have to be a Forgetter to feel this way.

From my cabin terminal I can access all the archival viewtapes of Knorol. When overwhelmed by the view outside I sometimes turn to the little screen to watch historical reconstructions, artists’ impressions of the surface of Ooranye in past ages, right back to the Hydrogen Era when the plains were mostly covered with forests of weeds, their waving pods so real in the movie that they menace my imagination, forcing me to sense the hugeness of Time and all its extinct realms, exemplified by the First Era’s savage vegetation and insectoids which threatened with their crossfire the scurrying forms of primitive man.

There was a knock on my door and it turned out to be the captain in one of his dissecting moods. “Free association: just ramble,” he instructed. “Vowel change from O to U.”

I got something this time: “Noun, Ooranye; adjective, Uranian.”

“Ah-hah,” he nodded.

“Have I said something interesting, captain?”

“Just a datum, just an element of the big picture.”

“Aren’t we Uranians always fond of the big picture,” I objected, “whether Forgetter or no? I mean, don’t we all have a tendency to enlarge our frame of…” I faltered.

“Ah-hah,” he repeated, grinning delightedly. “Note the way you say we Uranians. You’re tinged with context.”

“I’m what?”

“You view our world as one among many although we have never known any other.”

I stayed thoughtfully silent.

Choad went on, “We all do it. You’re right in that respect. We are all remarkably good at not taking things for granted. I’m doing it at this very moment, not taking for granted how good we all are at not taking things for granted. Infinite regress… semantic clowning… but we suspect that it is in preparation for some far-distant day.”

“A day when… what?”

“When we will be one people among those of many worlds.”

“So as a Forgetter I’m nothing special.”

“But a fore-runner is special,” he argued. “Studies have suggested,” he went on carefully, “that a blanked mind like yours is especially prone to suffer invasion from the future.”

“The pull of destiny? That doesn’t sound very scientific, captain. If I may say so.”

“Well, I don’t use that d-word, myself. I collect facts.”

That is true enough. He loves to collect facts. Actually, that’s all he wants to do with them – collect them. He will cite theories, but he never really wants to get anywhere.

He spread a chart on my cabin table. Our route had been ruled in black ink. I goggled at it: it was childishly simple – an absolutely straight great-circle line from Skyyon all the way to the Quonian border. 19,967 miles to be exact, from start to finish – the finish being the border checkpoint known as the Zark. It promised six and a half days’ flight at one hundred miles per hour, all in an exact straight line.

The Transect. Or, as I was tempted to call it, the Affront to the Intelligence.

“You’re frowning, Taldis Norkoten.”

I hedged, “This is how you do things, I know… but when I see the whole thing marked out like a blind slash through the night, I can only tell you, I feel it in my bones, that to be so determined to keep your straight line no matter what you meet, is to charge at fate, and – kind of – to tempt it.”

He shrugged, “We want an unbiased sampling route. Mathematically pure, untainted by human choice.”

“Let’s hope,” I smiled, “that not too many of your samples are hostile.”

However, nothing so far – apart from the marching spikes I mentioned – has offered fight during this voyage. And yet not even the most desperate battle could have made it more exciting, for me. Just to take quiet part in this flight into the unknown has been the greatest thrill. It has given me what I needed to fill in my sense of the world, to re-fuel the empty tank of my imagination; contentedly I thus watched as day succeeded day and Knorol soared over the transect route.

First, the richest Syoomean lands, from Skyyon in the direction of Hoog. Then past the Konteng of Nuvium. Then into wilder regions, till on this sixth day we have actually crossed the sfy-50 safety-contour which separates Syoom from its antithesis, Fyaym.

As we crossed that line I noted nothing specially visible; nevertheless it was a real boundary line, at which I felt a twinge in my nerves and a special beat in my heart. I ought to be able to say more than this. But it is like trying to pin down a ghost. Words being inadequate to convey the awe and mystery of Fyaym, one takes refuge in numbers and statistics. The books and view-tapes tell me that Fyaym comprises four-fifths of our planet’s surface, in order words, about sixteen hundred million square miles, quite beyond any man’s capacity to know or grasp. With regard to our own journey, Captain Choad tells me that from the boundary of Fyaym there remain 6,655 miles to the Zark…

I don’t think I am as scared as I ought to be, about what this ship is doing and what I must do when I leave it. Ignorance has its advantages. In fact isn’t that the whole idea? I’m rambling… but you asked for it, Director.

11,544,682 Os:

It was under an opaque black sky, during the deepnight of yyne, that we sighted the Quonian border.

By this time the crew had been briefed regarding the role I must play at the checkpoint.

Tarpik came to my cabin door and said, “Your time has come, you poor nebulated man.”

“You mean the captain has sent for me?”

“Yes. Says he wants to hear you arguing with yourself one last time.”

I hurried to the bridge and was startled and amazed by what I saw on the main forward viewscreen: a ribbon of metallic light stretching across the ship’s path from horizon to horizon.

The captain, uninterested in this grandiose view – which I myself ought to have expected – was focused upon a lower, tighter part of the picture. I heard him say, “That’s the Zeem already in dock. The delegation have arrived on time.” He then took note of my presence. “Your Director’s plans are on track, Taldis,” he said, motioning me to a seat in front of one of the small screens. “I have spoken to the Quonians and we are going straight down. Within minutes we must hand you over. As a last favour to me, please speak your impressions –” and he pointed to a microphone.

Grateful for the excellent treatment I had received on this voyage, I was happy to obey. While the captain directed the landing approach I muttered my final recording as subject of his psychological experiments:

“Er, well, here I am at last. The floor starts to drop under me and the ship begins its slanting descent towards the polikanomv, the Quonian frontier line. That’s one word of Quonian that everyone seems to know. And from what I’ve heard of those people, it’s no great surprise that their best-known term denotes what separates them from the rest of Ooranye.

“I was warned that there’d be no mistaking it. I can well believe that no other frontier defences are comparable to this. It’s actually a row of giant trees, spaces a couple of miles from each other, each a quarter of a mile high and shedding light to merge with that of its neighbours. The blended light from these trees – they are known as osror, plural osrorv, and it is their metallic fruit which glow – the light, I say, spills down to gleam upon the moat in which they stand. Beyond the moat, the land of Quonia lies dark at this hour…”

Pausing for breath, I heard the captain say to the chief pilot, “Careful of wind-currents, Gengr.”

“As ever, captain,” replied Gengr Axxan.

“Not quite as ever, pilot,” retorted Choad. “Remember, no foreigner is allowed to overfly Quonia by so much as an inch. In fact, better go for a vertical drop right now. Leave it to others to test the capabilities of the osrorv, will you.” He sounded quite edgy, not like his usual self at all. It was the only time I ever knew our captain to interfere with the details of piloting.

Gengr Axxan immediately punched switches to follow the order he had been given and in a few seconds we had sunk almost to ground level. From this point Axxan nosed us forward towards the waiting dock, avoiding any risk of an accidental encounter with the organic missiles reputedly hidden in the osrorv.

I continued my narration:

“I’ve heard that the Quonians are technologically advanced. Surely they must possess a sky-navy and need not rely upon pellet-throwing trees! But then,” I changed tack, “what with a twelve-thousand-mile border to guard, perhaps they do need them. Perhaps a defence system which grows and maintains itself is indispensable. Or perhaps,” I rambled on, “the polikanomv was around long before Quonia, and Quonia merely made use of it. I’ve heard that the osrorv’s questing roots melt and re-freeze the ice to cause a gradual displacement of the moat, shifting the land of Quonia a few yards per human lifetime…”

I halted my speech, conscious that I was merely re-hashing ideas which must have been discussed thousands of times. However, there was Choad nodding at me, expression approval and encouragement. Apparently he wanted me to go on; he thought I was doing fine.

I then realized that my contribution must lie not in my views or speculations, which were hardly likely to be interesting in themselves, but in the weighting of the phrases. The way I said things was what counted, no doubt, to a psychologist.

Humbled at this thought, I rounded off my commentary:

“Whatever the truth about the roots of the trees, and the trees’ weapons, the Quonians must also possess conventional weapons at this stretch along the polikanomv. For right here is a dim gap where no osror stands.”

As I spoke, the ship finally slid into dock. I peered through my viewscreen into the murk. “Here stands the Zark itself,” I ended, “and beside the checkpoint stands the town, somewhere before us.”

5: Into Quonia

“A-R A-R,” broadcast the captain in shipboard command language. All the crew listened. “Remember that as soon as the ship’s hull is in contact with the ground, any words we speak may be overheard by the Quonians. Security mode, operation nebulee.”

I felt a gentle bump as the airship touched down.

Completion of the transect from Skyyon to Quonia meant that the ordinary business of Knorol was over, without any need for captain or crew to enter the land of Quonia itself. The next survey mission would proceed from here in a different direction. But the captain had an agreement with my boss, Director Woth of Syoomean Intelligence:

Captain Choad would accompany me to the checkpoint.

He and I passed swiftly through the corridors and elevators of the airship towards the lower hatch. Farewells remained unspoken by the crew standing by. No one could be sure what surveillance devices the Quonians might possess. It was essential that I behave in character as a nebulee, and a nebulee would certainly not say good-bye.

As a matter of fact I was glad I did not have to speak. I found myself shockingly close to tears. Regret had ambushed me. The voyage had been so pleasant, such a comfortable way of getting re-aquainted with the world: I could have spent the rest of my life on mindless transects with the Survey Service.

Yes, these few days of rest and wonder had played the part of childhood in my new life as Forgetter. And well I knew that the sense of repose was irretrievable. Now I would have to “grow up”. Adolescence telescoped into the next few minutes…

The captain and I rode the exit platform from hatch down to ground. Then we trudged across a hundred yards of gralm to the lit entrance of the Zark. I felt the eyes of the crew on my back, projecting their sympathy through ports and scanners. The Quonians, I was glad to reflect, could not read our minds, could not know what the sympathy really was for.

As an agent pretending to be a victim of nebulation I was in double danger. I was entering their realm under false pretences, which any agent must do. But also I was taking mean advantage of our enemies’ adherence to a universal code of hospitality towards nebulees, and for that reason it would go all the harder with me if the trick were found out.

Choad’s reply, when I had put this to him a few hours earlier, had been typically whimsical.

“It’s a distasteful trick, yes, but it must surely come under routine expenses in the moral budget. I mean, disguise for a spy is so traditional.”

And the other side would do the same, given the idea and the opportunity.

The Zark loomed in the scanty light from its entrance. “Get used to this,” muttered the captain. I grasped what he meant. The outside walk. I was going to have to get used to approaching structures from the ground. Not only checkpoints but whole cities: everything in Quonia was built on the ground. No disk-on-stem structures here. He whispered, “They call our lofty cities arrogant; we retort that their possessive hugging of the world’s surface is a greater arrogance…”

Choad and I reached the half-buried polyhedral mass. We stopped before a door which was flanked by sentries in jointed ceremonial armour.

One of them spoke, first in Quonian and then, harshly but comprehensibly, in our own Nouuan tongue: “Your names and business?”

The captain gave his own name first and then explained, “My business is an errand of mercy on behalf of this man, Taldis Norkoten of Vyanth, who cannot speak for himself. He is a nebulee – whom I wish to leave with the Syoomean delegation that’s just arrived.”

The sentry muttered into his wrist transceiver, then nodded us past him. We entered a pillared hall where, despite the very late (or early) hour, an official reception was in progress. The hum of chatter filled the air; Syoomean ambassadors nibbled delicacies from a long table. Choad guided me forward by the elbow while I put on a dazed air that I suppose wasn’t too far different from my habitual expression. Choad called out heartily:

“Ambassador Trond, what a lucky coincidence! Lucky, that is, for this poor fellow.”

“Ah, Choad. Yes, our hosts have told me, you want to leave him with us.” Trond was a wide, heavy-jowled man with a routine smile.

“It is urgent that we do leave him,” Choad explained. “Our voyage continues further into Fyaym, no place for a nebulee. Whereas you will be entering a civilized city soon. A Quonian city to be sure, but they are a polite race, after all.”

I noted that he said this with no apparent regard for the ears of those white-robed Quonian waiters who were padding around us. It was as though he wanted to be overheard, wanted to annoy the Quonians. This applied to the Ambassador as well.

Trond asked, “And could you not stay a while?”

“If only it were feasible,” the captain declined. “Our next transect mission, starting from here, is subject to a time factor. Especially as we need to allow time to skirt the polikanomv. Of course if it weren’t for Quonian paranoia,” and he orated louder than ever, “we could have flown straight over their country, adding it to our transect, in which case, Taldis here might have been cured without leaving our vessel – if, as they say, the overfly of populated areas, the psychic effluent of millions of ordered lives, can restore the mind of a nebulee. Ah well,” he concluded sagely, “paranoia is for small minds. The small can’t help being small.”

The waiters padded and padded, bearing their trays, and their expressions remained blank. I had a queasy feeling in my stomach. If only Choad and Tronnd did not get such fun out of baiting the Quonians…

“You know,” replied Tronnd, “you do them an injustice. Narrow and retarded they are in some respects, but not small…”

So the captain and the ambassador continued to enjoy themselves, pretending not to know what they weren’t supposed to know, which was that the waiters were irrelevant, and that by far more sophisticated means the Quonian authorities were able to monitor every word that was spoken in their country. Doubtless both men had suffered various irritations from the isolationist Quonians, and now they were getting their own back.

One tall Quonian stepped forward. “Sponndar Ambassador,” he said smoothly, “observe your nebulee.”

I had distanced myself, disliking the way things were going. I moved to interrupt the game. Noises welled up in my throat, as I tried to sound like one who is about to recover his capacity for speech. “Hey,” said Tronnd, “listen to him; he’s benefitting already from being on the ground.”

I tottered towards the drinks stand. Everyone was watching me by now, but I acted like I didn’t care. Accepting a glass from the haughtily handsome Quonian at the stand, I bleared vaguely at his stony face. Like others of his countrymen in the hall, he was robed and cloaked in white; his skin, a lighter grey than mine, gleamed with that scrubbed, muscular health I had seen in martial artists from many lands. His expression contained the merest hint of scornful amusement. Despite his role of barman, the word that came to mind was aristocrat.

I sipped, looking bored. Then, asserting my independence a trifle further, I walked to the nearest window. I looked out and to my surprise, saw stars. Could it be refelc already? Then I remembered: yes, it could. This is Starside, the half of Ooranye that never sees the Sun. From this dark hemisphere the stars are seen for longer; both refelc and pmetn begin earlier and end later, each lasting many minutes longer than they do on Sunside.

Choad walked over and bade me farewell. I mumbled; he slapped me on the back. Then he walked out of the hall.

I felt lonely and miserable all of a sudden. What was I doing at this crazy espionage game?

After some more minutes a Quonian muttered to Tronnd. I paid scant attention, as I fought my depression. I tried to view myself as a contented pawn, or a minor character in a story, who must not expect too much.

A backgrounder, in fact.

The wave of misery passed. Presently the twelve Syoomean delegates plus myself were ushered up a ramp, round the hall’s side, through the back of the building and onto a terrace, outside.

We were level with the top of an embankment of hard-packed gralm seven yards or so above the plain. Visibility had greatly improved. The morning was starting to glow. The fading stars of refelc shone their last upon a metal rail that began at our feet and shot away to the horizon, promising to bear us into infinite adventure; a vlep hovered a few yards off to carry out the promise. Just a few minutes ago, vlep and monorail would have been mere words to me. Now, however, my eyes drank their fill and my imagination strained forward. This, I saw, was the regular morning train service from the Zark to the capital.

I saw Tronnd go to speak with the four Quonians who were waiting for us in front of the vlep. In my latest mood-swing, danger was just another colour in the landscape. Sure enough, the next thing I knew, Tronnd was waving the rest of us forward. The whimsical notion came to me, that old Diren Ev was right: I am a foregrounder, not a backgrounder at all. I am marked out by Fate to get away with things. A dangerous belief, of course. One risks becoming so arrogant as to be mentally ill. And yet – there is something to it.

It’s not mere imagination, or any special gift of self-confidence; it is a real exterior current which is bearing me along. I dare say the world is full of such “winning streaks”, and those who can step into them and ride are the “foregounders”.

Those who remain pedestrian (metaphorically speaking) are the “backgrounders”, such as, no doubt, the Quonian driver of the vlep, who had no idea he was conveying a spy into the heart of his realm, and my twelve ambassadorial companions whose role was mere cover for me.

Tronnd saw to it that I had a seat by the window, as though I were a favourite child being given a treat. The vlep jerked into motion and rapidly picked up speed. Air whined past the window glass; the plains blurred at a velocity apparently greater than anything I had experienced on the airship. The monorail ride was utterly smooth. Better say something, came the thought. For on this civilized, regular, grounded train, a nebulee should recover his voice.

“How fast are we going?” I croaked.

Conversation halted as all eyes turned to me. “Ah!” said Tronnd, “our nebulee’s brain-fog is clearing already! The answer to your question, stranger, is – four hundred miles per hour.” He nodded as my eyes widened. “Well, after all,” he added, “a vlep is the fastest form of transport on Ooranye. And welcome to our talk-see mission.”

“What is a talk-see mission?” I asked, playing my dumb part.

“A diplomatic junket with no specific objective,” drawled Tronnd. “A kind of safety-valve. To put it another way, it’s as if we and the Quonians are taking each other’s pulse. Reduces the scope for nasty surprises.”

“Thanks for taking me with you.”

“You are welcome. All civilized peoples will help a nebulee. Relax, don’t try to force your memories; just sit back and enjoy the journey.”

Under the brightening air the landscape became steadily more visible. Occasionally some near object streaked by, too fast for me to guess its nature, but most of the stuff in the middle distance I could identify: trees, groves, farms with square fields, and the gantries of compressor-factories that distil the luminosity of the vheic plants into the fuel-phials which we all depend on. More rarely we saw great cones in the far distance; I guess they’re cities. I built up a picture of a rational, predictable people. Dangerous enemies, no doubt, but strategic rather than random opposition. Yes, it ought to be possible to avoid nasty surprises in our relations with the Quonians.

I said, “I have another question or two.”

“My patience is equal to that,” smiled Tronnd.

“Where are we going and when do we get there?”

“Nullapz, the capital of Quonia, in about three hours.”

Normal exchange of crisp question and answer. Vigour of mind and common sense. Encouraged by looks of approval, I went on:

“Do you happen to possess a map of Quonia, that I could look at?”

“No, sorry.”

The atmosphere had changed. It was a sudden alteration. Only a slight “greying” of tone, but I was put out.

I shook off the unease and said: “Well, can anyone lend me a sheet of paper and a pen?”

One of the team did so. They all watched while I set the paper on the table in front of me and lifted the pen.

“Try,” murmured Tronnd with a nod.

A situation which I could not accept, which smacked of magic, loomed in that vlep’s cabin as my brain plodded muttering: “Well, if Quonia is roughly the shape and size I had gleaned from Knorol’s archives – that’s to say, an oval area nine million square miles in extent – and if we are going straight in, Nullapz ought to lie approximately in the centre of the realm. Surely I can sketch that much for starters: just an oval and a dot in its middle: what could be simpler? So why is my right hand not moving?”

I sat there gripping the pen, at first merely feeling a bit foolish, then creepily disconcerted. The muscles of my arm and hand would not obey me. My former sense of being in a “current” of good fortune veered now into a suspicion that a much bigger “current” was helping the Quonians.

I made vain efforts to speak out. Tronnd observed my struggle.

“Best to say nothing,” he nodded. “Sit back and enjoy the ride.” He, too, was not saying something, and I could say it for him: Don’t try to draw any maps of Quonia – it really can’t be done. Back off gracefully while you can.

One can’t even speak cartography here. Or complain aloud that one can’t speak. Only in these pages can the topic be expressed – because, for some reason, my private journal is still allowed.

6: Nullapz

11,544,687 Os:

In the second half of the journey the landscape became more crowded, with a thicker scattering of objects on the plains, and the flat smoothness more often interrupted by mountainous humps of metallic grey like upturned hulls shouldering into view. The closer of these mountains were streaked by rows and columns of lights, which grew doubts in me about the term “mountains”.

The meaning of what I see will perhaps become apparent to my controllers, if and when I get back to describe it to them, but meanwhile I might as well wholeheartedly be a Forgetter – though it might have been easier to relax into blank-mindedness if I had not done so much reading in the library on Knorol. Anyhow, the way I’ve figured it, I’m not even really a spy, I’m just a spy probe, an automatic gatherer of impressions. Questions can get put in store.

The last stage of the journey to the Quonian capital was dead quick: a blur of warm colour whipping past the vlep window, and then a wall leapt near and the view darkened as we entered the more high-built areas of Nullapz. Deceleration was sharp. In seconds we had stopped. We emerged from the vlep, with me tagging along like a stumbling moron. The usual solemn white-robed officials met us on the platform; they conducted us out of the station building.

Staring around in bewilderment I saw domes of fuzz, which after some moments became comprehensible as hemispheres of light enclosing blocks of buildings. The blocks were surrounded by smooth circular patches of ground, and strips of identical smoothness connected one dome with another. I was looking at ground-roads. No skimmers around here, not a single one. In any ordinary Syoomean city you’d see them hovering or gliding to and fro, whereas here, instead of that, vehicles went about on wheels.

One such ground-car awaited us. I tried to note our route as we wove our way in a stream of traffic to the embassy compound, but a half-dozen turns was enough to wipe out my sense of direction.

Finally we were led on foot into one of the light-hemispheres. We entered the building at its core.

No one inside appeared to greet our arrival; the building seemed unoccupied! Apparently, no permanent Syoomean embassy is currently resident in Quonia.

Our guides left us after handing Ambassador Tronnd the keys. When the outer door had closed behind them, it seemed we were left alone, but Tronnd raised one hand to command continuing silence, while with his other hand he took a torch-like device from his case and waved it around, making stroking motions as if to spray-paint the walls and ceiling.

“We can talk freely,” he concluded. He turned to me. “I do, of course, know who sent you here, Taldis Norkoten. But before I let you go your own way… Leran,” he called, “see to Taldis, please.”

A brisk young man of about my own age stepped forward: this was Leran Otmott, otherwise known as “Better Safe Than Sorry”. He led me into a small utility room, opened a safe and too out a small box, inside which lay a pill-sized device. “Swallow that.”

I stared at it dubiously.

He urged, “It’s a life-hook. For your own protection.” I decided not to argue. “Henceforth,” he continued as I gulped the thing down, “so long as you are alive, its signal will blip on our life-meter. What’s more, it will tell us fairly accurately where you are. The Quonians know we possess this capability, so it provides you will some protection – at least in peacetime.”

“So now I can go where I like?”

“And say what you like, too,” smiled Leran Otmott, “as far as we are concerned. Assume the worst – that you intend to defect – what secrets could you blab? None, in your nebulated condition! No, you can’t do us harm. And you just may do us good.”

“Then I shall go out this moment,” I said, and turned, as if walking on air, self-sufficient in my dreamy Forgetfulness. Leran’s superior manner played its part in propelling me away, but other gusts of emotion drew me: curiosity plus a certain pull, of what seemed like destiny or the “shape” of purpose. Out of the building I strolled, with only the clothes I wore and the contents of my pockets and belt-pouch, and the life-hook transmitting inside me. After all, are not all parts of the world equally fresh and strange to a Forgetter?

The mounds of illumination, the buildings they lit and the pavements which linked them, extended before me to the limit of vision, to show that I was in an enormous city. Yet how different from the idea “city” as I’d known it! I stood, not on any platform, but on the surface of the planet: an unfamiliar urban situation for most Syoomeans. Even I, the Forgetter, for a moment felt I was a squashed speck in this ground-metropolis; then I accepted the scene, and ventured along the pavement.

Among the tall, white-robed pedestrians and the drone of the ground-cars whizzing by, I got used to the Quonian speech which I could not understand, as my ear relaxed into the rhythm of its accents; similarly I soaked in the unfamiliar sights of Nullapz with unquestioning eyes, despite lacking the knowledge to give them meaning.

After some hours of this I became hungry. My pockets contained some Syoomean coins and it seemed reasonable to hope, this close to the embassy and the monorail terminal, that the local eating-places would accept my money. I followed a mauve glow-sign into a dining area, was shown to a table and handed a menu. What would I do, I wondered, if the waiter spoke no word of Nouuan, Jommdan or Lrissj? The only two words of Quonian I knew were osror and polikanomv! But the bustle of life around me was reassuring. Queuing at counters and seated at tables, the Quonians seemed messier and more human here, their robes less tidy, their chatter and their wriggly restless children all stamping my ticket to ordinary life. “Please,” I said when the waiter returned, “get me a snack and a drink, whatever your customers like most,” and it worked. Not that he understood. But that didn’t matter for I heard a female voice say in Nouuan, “Don’t worry, I’ll help you order.”

A tall lady in a satin gown was slipping into a chair at the table next to mine. Her male escort, of smart military bearing, smiled tolerantly at her intervention.

After the lady had translated my request to the waiter I was soon brought a plate of meat slices, fruit and bread, plus a tall glass of sparkling fluid. “By the way,” my benefactress said, “I am Miqua, and this is Anquit.”

“Delighted, but –” I added with my most thankful nod and smile, “it’s more than ‘by the way’, I’m sure.”

She uttered a tinkling laugh. “Quite right, we have been keeping an eye on you.”

“For my own good?”

The man, Anquit, replied: “Yes, nebulee.”

Miqua added: “Granted that city life is supposed to be good for those in your condition – you probably realize, don’t you, that you’d reached your limit.”

Anquit put in, “The limit of what you can fathom unaided.”

“I’m in your hands,” I replied to them both. Either I was sunk, or I wasn’t. “Taldis Norkoten, at your service.” As far as I could tell, I was taking only a small calculated risk. Woth had given me no alias. Therefore he must have had good reason to believe that nobody hereabouts knew me from previous missions. Anyhow, if this reasoning was wrong, and they did know me of old, it would not be any good trying to fool them by giving a false name at this late stage. Whereas being honest with my real name might salvage my mission if I could make real friends.

Besides, it is true, that without my former memories I am not the person I used to be.

“We have some free time,” said Miqua, enticingly.

“All help, friendship, advice are welcome,” I assured. “Already I’ve made strides, just by being in the crowd, but of course the more I get to understand, the more I can recover my former self.”

“We’ll recover it, don’t you worry,” she smiled. “Here we look after nebulees.”

7: The Blank Slate

Sophisticated Quonian society has received me with open arms. I have smiled my way through a whole round of parties where Miqua and Anquit took me as their guest. I’m grateful for their friendship and appreciative of the artistic wonders I have been shown, though the vaunted flower gardens fail to impress against the dark roof of the Starside sky or fend off the encircling presence of Fyaym.

Occasionally the Syoomean cloaks of Tronnd and his delegation swirl in and out of view in the blurred light. A couple of times they have approached me, for a brief, pointless exchange of banalities, monitored by Quonian listening devices. And now and then I return to the embassy, to write entries in my report for Director Woth.

Otmott, who gave me the “life-hook” to swallow, periodically checks its health by pointing a device at my stomach. He’s had little to say, but he once asked, “Have they tried to write their own views on your blank slate yet?”

“I haven’t encountered anything very political so far,” I replied.

“They will try.”

11,544,692 Os:

A messenger sent by my new friend Miqua drove me to one of the palaces and ushered me into a circular dance hall. By some trick the music seemed not to come from the central players but from banner-like streamers twirling in the air without visible means of support. Miqua threated her way towards me, then drew me to a couch-crescent, saying, “I’ll speak to you later if I may. Meanwhile, Taldis, this is Deldli, who has been longing to meet you.” I stooped to bow at a lounging, low-cut gown bursting with woman.

Deldli made a face at Miqua’s retreating back, burbling:

“I didn’t need her to tell me, you’re Taldis Norkoten, you’re the nebulated man from Syoom!”

“You make it sound decadent,” I grimaced.

“The Quonant says so,” she nodded. “He says, it’s always one’s own fault. No strong character ever succumbs to nebulation.”

“I see. A message from on high.” My own tone warned me to make the rest of my response mild: “I’m weak and lazy, I admit. In fact I haven’t done a stroke of work for quite a few days now.”

“Oh,” she said, sounding disappointed. “But allowing you to stay loose like this, I wonder… I mean, if your mind has been stripped of its civilized veneer…”

I had no idea what Miqua’s purpose could have been, off-loading me onto this character. But they were welcome to whatever they could learn from my emptied mind. Meanwhile I could keep trying to learn from them… “Well, what do you do with your nebulees?” I asked.

“They get sent to a place…”

“A sort of institution?”

“I believe so,” she nodded vaguely.

“We don’t bother to do that,” I told her. “Syoomean policy is to leave folk like me alone. There’s no risk at all in letting my sort run free. Nebulation only blanks our memories, not our inhibitions – those remain intact! So don’t worry that I might cast off all social restraint – I shan’t!” But at that point my inner alarm bell rang to warn me that nebulation might not really be the subject of our conversation at all. It might be a probe to discover what I really am. And if, at this gathering, somebody were to mention the Forgetters by name, and if the room had face-readers or lie-detectors, I’d be caught.

I caught sight of Tronnd, excused myself and went over to him. He had just finished a dance, his glamorous partner still dangled on his arm and I guess he was none too pleased to be accosted by me. “Lost your way, Taldis?”

“Socially, yes,” I admitted. “I’m making friends so fast, I’m at risk of losing my head.”

He disengaged himself from his lady friend, saying, “Excuse me for a moment, Atalsa, my confused young compatriot here needs a bit of guidance.” To me he growled, “What do you want to know?”

“How much can I tell them?”

“About what?”

“My impressions of Syoom…”

He made a swift pronouncement. “You can say what you like to them. No need for you to feign ignorance. Muddy their waters as much as you like.” This bit of unsympathetic advice, shoved at me like a pole, made me face the fact that I was on my own.

A hand fell on my shoulder and I looked up into the twisted smile of Anquit, Miqua’s young man. He said affably, “How’s our classic case doing?”

“Fine, thank you.” (Meanwhile, Tronnd took the opportunity to drift off.)

“I was just asking myself,” said the Quonian, “why isn’t the Ambassador more worried about our social investigation of your blank-state mind? Does he have some special confidence in you? Is he aware of some power in you? Or come to think of it, is he beginning to worry after all? I notice his face has gone rather glum.”

“You amaze me,” I said, speaking like an innocent nebulee. “What I need, in my condition, is clarity, not mystification. Keep things simple, please.”

Next thing I knew, Miqua had arrived at my other side. She squeezed my arm as she drew me away from Anquit, and over her shoulder she rebuked him: “You don’t have time for annoying games with our guest; you need to get back to your post.”