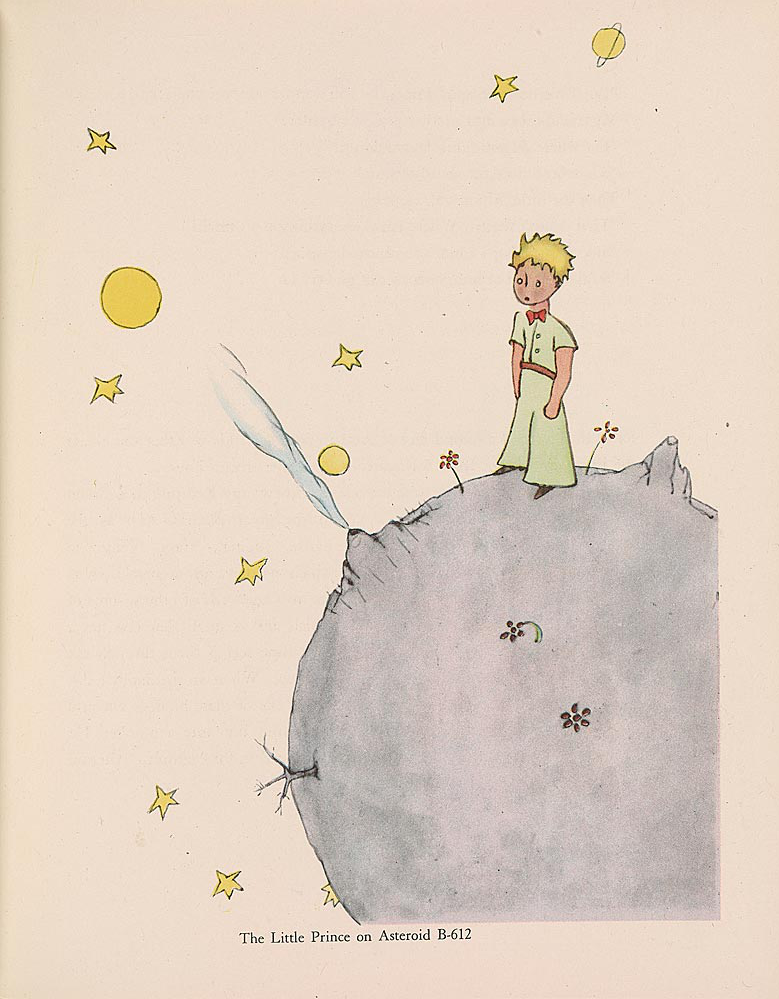

the little prince:

the humanistic asteroids

and the lonely earth

of antoine de saint-exupery's

le petit prince

by

antolin gibson

One of the most interesting explorations of the Asteroids was undertaken by the inhabitant of Asteroid B 612. The traveller visited Asteroids 325, 326, 327, 328, 329 and 330. The first was inhabited by a king, the second by a vain man who wanted only to be flattered, the third by a drunkard, the fourth by a businessman, the fifth by a lamplighter, the sixth by a geographer. All show various aspects of human hope and folly and delusion. All well-known – as are the baobabs which are threatening the very survival of Asteroid B 612 – for all these affairs of the Solar System are described in the classic Le Petit Prince by Antoine de Saint-Exupéry.

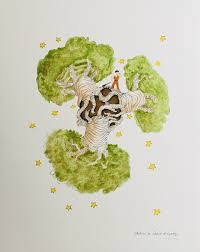

asteroid wrecked by baobabs

asteroid wrecked by baobabsLe Petit Prince – concerning survival among the Asteroids and upon the Earth - is a study of loneliness, first and foremost, and the failure of human relationships, personal and communal, to overcome this great plight of humanity. In the meeting with the fox, for instance, the idea is reached by the Little Prince that friendship is a kind of taming of one or another participant, which destroys something meaningful and crucial in the spirit.

The Little Prince meets the author in a desert upon Earth - they are both pilots, both marooned, adrift, each in their way desperate for some inner resolution: the child is in search of a friend; the adult too is desperate for contact, but also to repair his damaged plane, and working against time to do this, lonely, thirsty, and starving.

They almost truly meet, almost their spirits coalesce in understanding, but the stupid alienating world of “Les Hommes” is like a ubiquitous edifice all around them – ever there, even if for the moment beyond their sight.

There are fragments of exceptions to this pessimism, spinning out into the universe, elusive and poetic. The Lamplighter on Asteroid 329 is perhaps their symbol but the permeating feeling even so is that we are always alone, we can never truly meet one another, trust or know one another.

The author’s Terre des Hommes with its crucial link with Le Petit Prince in its conclusion, is a lament for Childhood lost and – with the symbolic and mythic role of the aeroplane – there seems to be some kind of solution after all to the predicament of humanity, residing in a lyricism of spiritualized mechanization, a solution to the materialism of a scientific age.

The aeroplane is to Saint-Exupéry what the motorbike is to Pirsig, but the former’s paean to the value of technological advancement in Terre des Hommes is, as with the work of Olaf Stapledon, coupled with the sternest warnings against the divorce of science and spirituality. If it were not for this, Saint-Exupéry’s work would be on a level with Hemingway’s comprehension of Man – or perhaps one should say “Manhood” – in the unending contest with adversity. For Saint-Exupéry, spiritualized humanism is fragile, and of course we see this most clearly with the breakdown of the aeroplane in Le Petit Prince, and the breakdown of the pilot and – in some ways – his tragic friendship with the child he meets, and the bridge of understanding that is almost made between them.

In the author’s Vol de Nuit the aeroplane is indeed most like a spaceship; the villages it flies over are lonely worlds the pilot will never truly know.

The journey among the asteroids as well as the journey over the glimmering villages of earth are in fact more than the symbol of spiritualised humanism, or any patterned religion that seeks to explain, or put off explanation, of the universe. The instinct and fulfilment of the journey – and of life itself – is instilled in the Little Prince. It is simply the gentleness of determination.

watching the sunset on an asteroid

watching the sunset on an asteroid