kroth: the slant

10: hungry horizon

I opened my left eye.

My gaze met sky: it had become duskier. Without yet raising my head to look, I sensed that the sun had just disappeared behind the Slope.

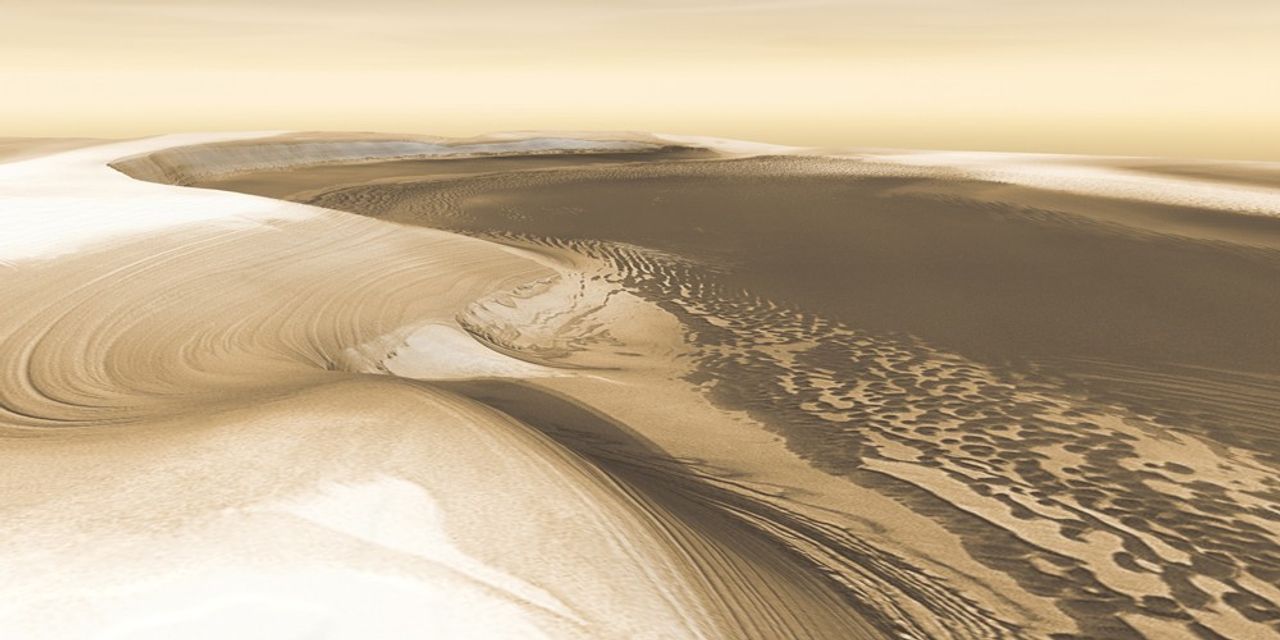

My eye followed the line of my out-flung left arm which lolled southward. Beyond my hand, grassland, interspersed with small patches of forest, extended down the slope of the world, till it met the deepening blue of the sagorizon.

Maybe half a mile off, moving figures were visible in the gloaming: Gonomong, on their mounts. I stared, awake but hardly knowing it. Those figures –

In retreat?

Yes - into the distance: a shrinking, dim multitude of decapods, carrying or in some cases dragging their fallen masters.

Stickiness smeared my right cheek, which rested on my shoulder; some noise issued from my throat. Other groans and whimpers, coming from behind me, penetrated my woozy consciousness. Screams broke out, and were just as suddenly cut short. I tiredly closed my eye, but continued to listen.

Next thing I knew, my wrist was held, then released. “This one's all right, I reckon,” said a voice.

I opened my eye again. A youngish man squatted beside me. The twilight had dimmed somewhat; real night had not yet fallen. I must have passed out again but not for more than a few minutes.

“You're all right, mate, aren't you?” the man said, sounding fairly sure about it. I also saw the boots and trousers of a companion standing to his right, one knee bent in the typical slope stance. A satchel rested on the ground between them.

“Yaaagh,” I said, or words to that effect.

“You were born lucky, I guess. Flung out this far, yet no bones broken; I'd call it a krunking miracle.” The squatting man shook his head in wry admiration of my good fortune, stood up and reached for the satchel. Just then I heard some more screams, from a different direction than the first lot. The man said to his companion, “That one next.”

“Urrgh?” I called.

He looked back, and advised: “Just get up when you can; there's no hurry. We've got more urgent cases than headache to deal with!” He and his companion, who was carrying a folded stretcher, walked past my head.

“Wait – ” I was able to croak. “We won?”

It was the other man who spoke this time. “Of course we won, ye daft bat! D'ye think the doctor and I'd be picking up the pieces otherwise? I tell ye, if we'd lost this scrap, we'd ken nothing about it.”

“Sorry,” I mumbled.

“Don't be sorry; be proud. You laddies have done yer job well. Sent the Rip-Mig reeling for a generation, in my opinion. Things can only get better from now on.”

Propped up on one elbow I twisted to look where they went and I saw maybe a dozen or more other medical teams picking their way among strewn bodies. I sat up, while waves of dull pain sloshed in my head, and got my right eye open, there being nothing wrong with it except for some blood stuck around the lid. I felt terrible and lucky and guilty and joyful at being alive. I tried to shut my ears to the agonies of the wounded. I had to look, though, because my nervous system was still half keyed up to battle, a situation in which you have to see what's coming.

The base of the embankment was about six or seven yards from where I lay. Most of the bodies lay along it, like snowdrifts against a wall, though a sizeable minority, like myself, had been flung further a-field by the force of the rout. Hundreds of bodies, all in the blue uniform of the regular army or the brown jackets of the militia. We had won at fearful cost. But why could I not see any dead or injured Gonomong?

Well, it would have taken more than this rout down the embankment's south side to kill those mounted men; their steeds would have retained their footing. The dead Gonomong were the ones who had been trapped instead on the Vallum's north side, hidden from where I was. The triumphant, the exuberant Gonomong, who'd streamed through the gap they had punched in our line, and fanned out in their drive to surround us completely – they were the ones who must now be lying mangled and pulped in the avalanche that crushed them. We had won because as it turned out they had after all been stupid enough – forgetful enough, in their elation – to put themselves in the path of the Marraspang.

As for the rest, the survivors…. I remembered the retreating forms I had seen southward. Turned once more in that direction, I peered in fascination through the deepening twilight and saw, very obscurely, that the defeated survivors were still visible, though now too far away to be distinguished as individuals. Evidently, no attempt was being made by our side to pursue or harry them. Having given them a beating we were allowing them to recede into the dim depths of Slantland.

Perhaps we lacked the strength to prevent their escape, but I guessed, also, that it might suit our policy. Tales told by the surviving Gonomong would serve our purpose. The terrible surprise that had turned the tide of the battle, as it gained in the telling, would inspire such dread of Topland's ingenuity that it might earn us a generation of peace.

From this, another overwhelming truth burst upon me, namely that the previous overwhelming truth that had burst upon me was actually a load of rubbish. Topland's strategy, far from being fatally flawed, had been vindicated; our general actually did know what he was doing.

*

A lone, abandoned, riderless decapod - one curious minor exception to the enemy's retreat – was crouched about twenty yards from me.

Its four back limbs and its six front limbs lay flat on the ground; between them, the central length of body arched like the curve of a capital Omega. Its head-shield lay tilted back which allowed me to glimpse a blunt face somewhat like that of a tortoise. At that moment, as if suddenly aware of my gaze, it moved its head slightly round. I hastily looked elsewhere, purely as a reflex, to avoid eye contact. Why? I didn't know why. I felt no aversion for the creature. Nor could I see any reason to fear it.

Meanwhile, lights came on as technicians strung up lamps on aluminium poles, the closest of them not many yards from where I lay. Soldiers, medicos and nurses were moving around, setting up a field hospital with equipment lowered on ropes from the Vallum. Everything was placed on platforms which in turn were set up using standardized wedges or “chocks”, bevelled to compensate for a 30-degree Slope. I admired the practised rapidity with which the chocks were placed to serve as foundations for planks on which, in turn, plastic bricks were laid, building up to the larger platforms for beds and tables.

Amid all this activity, no one tried to approach the decapod, or, alternatively, to shoo it away. People ignored it. They wanted nothing to do with it. If someone unthinkingly approached within a few yards of it and then became suddenly aware of the thing's proximity, he or she would shrink away.

I thought, that creature is staring at me. Just on the edge of the illuminated zone, it sat waiting. Was this a melodramatic way of describing it? For a human, a “wait” implies purpose; I must remember that this thing was only an animal. Yet the fact remained, that while far off in the gathering night its defeated brethren were retreating southwards, this one lingered…. Of course, I repeated, it was only a beast. Should I let myself get jumpy at being stared at by a decapod? No, and yet – A nebulous suspicion came into my head, that in some way or other the battle was not yet over for me.

Part of my problem, no doubt, was a stupid sort of guilt at having got through it all intact when so many of my comrades had been killed or maimed. A kind of embarrassment at being a favourite of Providence. I found it did not help to say, “accidents will happen, including accidents of survival”; I could not accept pot luck so easily. I became receptive to the fuzzy idea, that I was alive because I had a debt still to pay.

I eventually scrambled upright. A nurse saw my swaying step, hurried towards me, grabbed to steady me and said, “Come on, I'll clean you up.”

She escorted me towards a zone marked out by folding chairs and a wash-stand, an area for those like myself, the dazed but not too serious cases, the lucky ones. I allowed myself to be led, and while the nurse removed the caked blood from my face, I encouraged myself to relax, to quieten the core of horror which still quaked deep inside me. How absurd to be jumpier after the battle than while it raged….

“Wemyss,” said a weak voice.

I did an eyes-right and saw a man with a bandage round his head, resting in one of the chairs. He said, “Glad you survived.”

I recognized Murena. “Captain – great to see you, sir.” And it was great, even though I had never particularly cottoned to him. For he was doing something which deserved an affectionate hurrah: he was continuing in existence, he was alive.

“Seen any of the others?” he asked. “Our company, I mean.”

“No sir, none yet.”

“Don't reckon we will. Not many.”

“But, sir, we did it: we won the victory.” A pause.

“Yes,” he murmured. “We had to win. It was that or kerunk.”

“No chance they might, er, mount a counter-attack?” I inquired. I was glad he hadn't said anything cynical, but I wanted at the same time to rouse the old Murena disdain.

He replied in a rambling style which wasn't much like him.

“Gonomong counter-attack now? If there were any chance of that, our look-outs on Neydio would tell us. Infrared scopes they have up there; turn night into day.”

“I hope so, sir.”

“You 'hope so'. Breathe again, Wemyss - the war's over.” The curt Murena, the one I knew, was back again. He added, with a dry husk of a laugh, “We put such a scare into the Mongees….”

“For another generation,” I nodded.

“That'll do me. One whole generation of peace? I'll be satisfied with that.”

I on the other hand, no matter how much I wanted to sit back and enjoy the miracle of life after the prospect of death, could not yet relax. Conscience was a needle between my shoulder blades. Get up, it said, and see to one last job, after which you will be allowed to enjoy your luck.

But I've already done my bit! I fought all through the horror and came out the other side!

Yes, with the aid of that extra allowance of luck, for which the bill has now arrived.

You don't mean –

Yes. Turn around.

You may theorize, you may think you understand, that the transition from battle to quietness, from dire peril and the expectation of death to sudden safety, is likely to be as unhinging as the opposite change, enough to make a fellow begin to hear voices. You may decide that what was wrong with me was my inability to unwind, to cope with my own relief. Or you may more superstitiously say that I was experiencing the far-off sucking pull of the insatiable sagging horizon. Howsomever, the reasons for my action are debatable.

The nurse had finished with me; no one, except possibly Murena, was watching me. I swivelled in my chair. The voices around me grew faint, while pesky Conscience grew louder, and I found myself staring once more at the placid decapod.

It sat isolated, shunned by all, as it munched grass in the half-light on the edge of the hospital area. See? You cannot refuse the opportunity.

Opportunity?

To ensure that today's horror will not happen again.

I could, I must, rise out of my chair. All right, Conscience, I know, I know, I will confront the creature….

Though drained of most of my energy, I felt basically sound and whole. Ready for a final gasp or two of effort, I was nerved by a spirit of resolve that seemed to blow into me from the night breeze. It was a surge of trust: a conviction that honesty in the long run really does pay: a decision to face the truth, the real reason why I was alive and unhurt.

It was not at the very foot of the Vallum, not on the heap of the fallen, that I had recovered consciousness after the battle. It was at some distance from there that I opened my eyes. If chance really did fling me so many yards away from the rest, then no bodies can have broken my fall, so I ought to have been seriously injured, probably killed.

So it didn't happen that way. I did fall with the majority. But then that thing picked me out, dragged me from the heap, dragged me several yards until, to avoid discovery, it withdrew to wait.

Now I was walking towards it. One ruby eye fixed on me, it was tearing up some grass when it saw me approach. Its jaws ceased to work. Then its head and front paws and the whole front third of its body subsided, lay extra flat and still, and waited for its new rider.

Confidence came to me from I knew not where. I was convinced I was about to do the right thing; the basis of this conviction was an unidentifiable cotton-wool blur of assurance, floating without logical support. Sharper reasons did exist, but they weren't what made me dare. My motives remained fuzzy until – as my strides brought me closer – details came into focus and I became overwhelmed by the creature's fitness for its role of steed. In place of arrangements such as saddle or stirrup, the shape of its body was adapted in detail for conveying humans: its hide was stepped and flapped where the rider's feet must go; its ruff provided protection for one's legs; the holes in the head-shield were positioned for one's eyes to see through….

If war is to be avoided in the future, or at least made less costly, we Toplanders need to beat the enemy at their own game – learn to be properly mobile in Southern latitudes – meet the Southern powers on equal terms, instead of cowering behind walls or relying upon avalanches.

I, the dreamer of Earth, free from Krothan phobias, free from Topland terrors, free from any Northern antipathy for the worms of the South – I shall be the first “shonk” to master the steed of the Gonomong.

All this was true, but it wasn't enough to explain how I dared, or how I succeeded. What really did make me do it? The pull of destiny? Not a nice idea, really – being pulled by a force. You don't know where it's been. Especially a force that pulls down-Slope from the lands of terror.

“Hey! Look what that feller's doing!” cried a startled voice.

“Quiet!” hissed Captain Murena. “You – fetch the Colonel. You – find me a camera.”

The decapod had reared, revealing the mauve stripes down its front, whereupon I remembered that I had seen this particular beast during the battle. Now its front paws waved close to my face. Then it lowered itself again and fawned on me, rubbing the edge of its head-shield against my side, gently nudging me round to where it wanted me to step up. In another moment I was astride it.

“Great krunking gadrop,” called another voice. “Will you look at that?”

“Quiet!” repeated Murena. “Nobody interfere.”

I wanted the creature to rise to its feet, and no sooner had I formulated the thought, than it rose; I wanted it to take a step forward, and immediately it did so. The fuzzy blur in my brain, the cotton-wool presence, was, it seemed, one end of a psychic conducting rod, the other end of which extended into the decapod's brain. Krunking gadrop, indeed. And yet swear-words seemed inappropriate. It was all happening as smoothly as a lullaby.

With effortless skill, borrowed free of charge I knew not how, I took the decapod through its first paces under my command. You have seen an inchworm move: the front end goes up, quests for a moment or two, goes forward and down, and then the rear end likewise goes up and forward and down. Imagine you're sitting near the front end of a giant version, just behind a kind of prow that is formed by a head and two front limbs raised on a neck that extends beyond the central arch. You might think that the up-down, up-down motion would make you, the rider, sick. But actually it does not feel that way. A fuzzy blur in your head, a rapport and command link, provides constant and instantaneous feedback, so that you experience the thing's movements as properly yours, as quite natural and expected. You don't in the least mind the up, down, up, down. I'll put it more strongly: you hardly even think of it. When, in an everyday situation, a man wants (for example) to raise his arm, his inner command and the act he performs are, so far as he can tell, simultaneous. To my amazement, my control of the decapod was just like that. No sooner did I think to wish it to move than it moved in obedience to my thought. It might as well have been a part of me.

“He makes it look easy,” commented Murena.

“Too easy,” came the clipped response of Colonel Reece. He arrived with a look of glum disbelief on his thin face. “Meanwhile, captain, I note that everyone else round here has seen fit to stop work to watch this curvetting.”

“Perhaps they need…. need to witness….”

“And what, may I ask, are we witnessing?”

“History, sir,” said Murena.

Indeed the crowd continued to swell and it was not long before my little area of grassy Slope was surrounded by men who evidently were not quite exhausted by the hours they'd spent fighting for their lives, men who still had the energy to come and gawp at something new. They must, I thought, be as crazy as I am. But then after all why should I be the only one who had sensed unfinished business at the end of the near-death experience which we had all undergone today? Why shouldn't I be given moral support? That, no doubt, was why I sensed no actual hostility, despite the distaste I could see in the drawn faces around me: they saw the point of my efforts, they understood, or at least they intuited, that I was trying to see to it that the war was properly finished off, that the whole nasty episode could be filed “closed”.

Of course there was bound to be a lot of argument. I could hear the murmurs, and the lamplight revealed to me the faces on which fascination, even admiration, contended with disgust and loathing. Colonel Reece's expression of wincing amazement was no different from the crowd's average. While he conferred with Murena, I went on with the demonstration, I turned in various manoeuvres, meeting the stares on every side with a stare of my own in which I packed as much confident reassurance as I could. Finally the Colonel called out to me:

“Wemyss! How can you control that thing?”

I could tell by his tone, his question really required I prove to him that it was not controlling me.

I shouted back: “It responds to thought control, sir.”

“Tell it to turn three times clockwise.”

I did so and it happened.

Reece nodded, “I'd rather believe your explanation, than believe that it heard me and knows English. Now listen carefully, Wemyss. This business could be big, but we've got to make sure we finish it properly. Suppose you want to get down, what will - No! No! Don't actually do it; just tell me. I see, I see.” For I had ordered the decapod to let me off and it had begun to descend into its crouch.

Reece seemed satisfied. “Don't get off yet,” he emphasized. He spoke to someone by radio. Then he said: “We can make a start. Clear a way, you people….” and he began to snap out orders for an escort of spears to form around us. “Now then, Wemyss, start moving. I've found some secure quarters for you and your mount.” Further orders – by radio, these – must, I guessed, concern what was to happen at the other end of the rapidly organized procession.

“Am I under arrest, sir?” I hazarded.

“You're not a prisoner, but your mount is. As for you, you're a hero. So shut up and co-operate.”

Not wishing to receive another blast of what I took to be irony, I obediently refrained from asking any more questions. I had done what I could. My task was over; for me the day was done, really done, at last, and I hardly cared whether they took away my liberty or not, so long as they put me in a room with shower and clean bedding. The exhaustion which I had so far kept at bay now took possession of me so that I could hardly move a muscle, and only the fact that I rode by means of mental command enabled me to continue. Follow orders, I told myself, and don't try to think ahead.

We approached a space at the foot of the Vallum that was now cleared of corpses. Boards had been placed over the bloodied ground, wide enough for us to tramp over.

Up the Vallum's south slope, we progressed; going home now, I thought, groggily. The escort carried torches, whose beams swung this way and that. In addition, little blue-white glares, from ground-lamps shining up into our faces, began to line the path we took, as the Army's technicians went to further trouble to light the way: not so much a torch-light procession, as a cats'-eyes procession, I thought in sleepy wonder. The effect flowed up to the top of the embankment, to the battlements. My decapod then stepped, my escort clambered, over onto the Vallum summit, where I averted my eyes from the havoc revealed by the torch-beams. Switch off, I wanted to shout: I don't wish to see. Yet the veil of night in any case couldn't cover the horror, couldn't abolish – rather, worsened – the smells and the stumbling. Despite all this, peace crept into me; the tired-out sense of a part played, disgrace avoided, approval earned…. all rewarded with permission to surrender to weariness.

We crossed over, to the north edge of the embankment; here the line of lights continued over the planks of a bridge which must have been thrown together with impressive speed, to reach horizontally from the Vallum to a point on the Slope beyond. Why had such a bridge been built? No need to ask: this was where the great mess lay, the gruesome mash where the boulders had come down. Some of my escort played their torch-beams over horrid fragmentary sights which my eyes skidded to avoid. I thanked the new bridge for saving us from having to clamber over the great rocks and wade through the crushed remains amongst them.

Faraliew, I reflected, must take responsibility for this. He it was who composed this scene; he must have given the actual order, whereupon the rocks rolled and rebounded to their rest amid the splashed and pounded meat. He – none other – had spoken and it was done.

What a way to earn a mention in the history books.

I did not try to be fair, to weigh points for and against his military decision; my mind simply gave way to revulsion. My hatred of what had happened flowed up to the general in command, and, past him, flowed higher still. The sheer ghastliness of it all shocked my entire belief system into a new shape.

An “Act of God” – that was how an insurance company would refer to a naturally occurring avalanche. But if Nature's acts are God's, and if Man is a part of Nature, it follows that all manifestations of human wickedness, including wars and battles, are also Acts of God. In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth…. and in so doing He unleashed an avalanche of cause and effect which had evidently escaped from His control. “God,” thought I, “You have acted irresponsibly.” In my present black mood I told Him that He ought not to create any universe which was liable to lead to something like this; it just wasn't worth it.

I had meant well, I had wanted to do my bit, to fulfil my sense of obligation to the society of Topland, the wonderful yob-free civilization to which I was proud to belong…. but I hadn't joined up in order to play a part in a massacre.

Admittedly – so I conceded – He has earned high marks for having created all that is splendid and loveable. But what's the point doing that and then smashing it up? Or rather, letting it be smashed up (for I was now convinced that He had lost control).

So my view shifted. I thought to see God's career on Earth in a new light. My religious background (my mother had brought me up as a Congregationalist) turned out to be insufficiently strong to stand up to the test of battle, or rather, of the aftermath of battle, and so a host of new perspectives came crowding in on me all at once. Christ's ministry, instead of a triumphant turning point to put mankind on the path of salvation, now seemed a desperate rescue attempt, or even less, a mere morale-boosting exercise like dropping Allied propaganda leaflets into Nazi-occupied Europe to reassure the oppressed that they had not been forgotten. Well, maybe a bit more. (I struggled to be fair.) All right, it was a new voice in history, a new kind of voice. Nevertheless, the status of the One who uttered that voice was reduced in my eyes to that of a mere hero, a basically good guy who was out of his depth, a beloved leader but (this was most unfortunate) definitely not a sure-fire winner. The odds against Him were too great; by which I really meant, that my former belief in God's omnipotence was a position I must retreat from if I was to continue to believe in His goodness – and without that belief there isn't any point in bothering with religion at all.

And because I could no longer believe in an all-powerful benevolent God, the field was left open, unfortunately, to belief in another sort of power. Not that I believed that a Satan existed; not yet. But conditions seemed right for fragments of a potential Satan to develop. Light-headed thoughts, dark imaginings assailed me with ideas of emergent evil. “Bits of Satan must assemble,” I slurred, “unless we do something…. do something….”

Well, it had been a tiring day.

*

The procession came off the bridge, away from the scene of carnage, and proceeded up-Slope towards Volost. In a few minutes I saw that we were headed for the illuminated front of the Volost Hotel.

The building's main east-west front and its two north-south wings all formed three sides of a square; now the fourth side was also walled, by a hastily constructed fifteen-foot fence, the centre of which swung aside on hinges as we approached.

The escort stayed behind me; I rode into the corral, and carefully and silently ordered the decapod to crouch down. It sank, it aligned its snout with the ground and I dismounted without a hitch. I turned, saw the line of spears, all of them held tensely, in the hands of men who were not sure, even now, what to believe; as the decapod lazily tore up some mouthfuls of lawn and began munching, I walked towards the exit and the spears parted and made way for me. Colonel Reece said: “Well done, Wemyss. It seems you really were in control.” He turned his head and spoke formally to an aide: “Halton, see that a watch is kept on our new prize. Topland has waited a long time for this.” To me once more he spoke: “Congratulations, man!”

I looked back as they closed the gate. The creature now appeared to be dozing like a contented sheep; I wished to do the same. Dulled by fatigue, I was slow to respond to the Colonel's congratulations. Reece stepped forward, grabbed my arm and put on a smile. “Wemyss,” he hissed, staring into my eyes, “don't go all absent-minded on me! Snap out of it.”

“Yessir, sorry sir.”

Rapidly he continued to bite out the words: “Do you know, I am quite happy to have risked my career by allowing you onto our territory with that thing, because I am trusting that you really are a hero. So be one!”

“Of course. Of course,” I repeated dreamily.

Reece let go my arm and muttered to Murena, “He's like a damned zombie. He'd better not let me down.”

“Put him to bed quick, that's what I suggest, sir, then go see the General.”

“Yes – this is one issue I won't be sorry to dump on Faraliew.”

A gentle push at my back, pressure at my elbow, and I was coaxed into a walk, round the front path towards the main entrance of the hotel. I was not inclined to speak. I understood what was bothering Reece, but I could not feel any concern. A couple of times he addressed me, muttering hesitantly, “How's the brain, Wemyss?....Feel anything funny in your mind?” I feel fine, sir, I could have said, but I was too worn out to bother. Too exhausted to give him the reassurance he yearned for, reassurance that he had done the right thing. Let him fear; it was just too bad. I knew that my thoughts were my own, my mind was still my own, not some alien-influenced cuckoo in the nest of Topland. I had changed my religion rather rapidly, but no one need know about that. One day I might tell Uncle Vic, if I ever saw him again….

These thoughts passed across the dim backdrop of my fading awareness as I was led through a lobby and up some stairs till we stopped just outside an open bedroom door. The number of beds that were squeezed into that room, and their wheels and frames, reminded me of what I had heard, that the hotel had been requisitioned for use as a military hospital for long-term cases; was I a long-term case? No, if only I could have a good night's sleep, I'd show them, I'd be bright as a button tomorrow morning…. Other patients were being wheeled out. Then, in I went. Nurses came and washed me, dressed me in clean pyjamas, enveloped me in the fresh crinkle of crisp bedclothes and left me to sink into oblivion.

*

Morning light slanted through the window. A well-built blonde nurse was bending over me. The name badge on her bosom read “Belinda Brown”, which, I thought, had a nice ring to it.

“And how are we today?”

“Fine,” I replied, and meant it: I had awoken warm and relaxed, full of well-being.

“You've had a touch of fever. But,” she felt my forehead, “it's better than it was.”

Fever? Yes, come to think of it, I did sense it, lingering but not enough to spoil my appetite; I felt ravenous, and grinned ecstatically when Belinda said, “Ready for some breakfast?”

She slid one hand behind my back, lifted the upper half of me with no more effort than if I had been a three-year-old, and slid more pillows behind me. Then she handed me a breakfast list and asked what options I wanted. “All of it, please,” I requested – ready to find out how much I could get away with, but also ready to pretend that I was joking if need be. Belinda put me in mind of a feminine ju-jitsu expert I'd seen in some film, and my instinct told me to stay on the right side of a girl like that.

She took back the list and ticked every item for me. “I like a man who knows what he wants,” she remarked in a cheerfully saucy tone, and departed.

“Wow,” I said when she returned with a loaded tray, and I did full justice to the fullest English breakfast ever. Afterwards, the nurse helped me up. I was surprisingly weak on my legs, though after she had got me to the bathroom door I was able to persuade her that I could manage thereafter on my own. When I came out, she pointed back to the bed and I meekly obeyed, but I began to wonder. What exactly was supposed to be wrong with me? Battle fatigue? Did that really explain the pampering?

I had no objection to being coddled, up to a point, but the government surely lacked the resources to give this VIP treatment to all the able-bodied survivors, so some explanation was wanted.

Either I must be weedier than most, or I must have been singled out for the special treatment for another reason. That I was being rewarded for my taming of the decapod, was an explanation which rang false. You don't (or at any rate, you shouldn't) reward a man by isolating him, or embarrassing him.

I watched Belinda as she pottered about, tidying this and that. Nurses must be much in demand right now, yet this one seemed to be hanging around, spending rather a lot of time in sight of me. My growing suspicions were becoming clamorous; I wondered how to quiet them. Well, one good rule is, pick a person you like the look of, and start a friendly argument with that person.

“Nurse, can you tell me where my clothes are?”

“You can't get dressed just yet.”

“Am I allowed to know why not?”

She straightened, arms akimbo, and looked at me squarely. “Take my word for it,” she said, “you're biting off more than you can chew.”

I felt a bit light-headed as I retorted, “Better than lying here chewing more than I've bitten off.”

She went a bit red. “I was told not to let you have your clothes just yet, but…. well, they said nothing about not letting you take a little walk in your pyjamas. As far as the rear garden, anyhow. Let me check.” She went out into the corridor.

A minute dragged by, then another, and I simply had to get up. I went to the door, looked to the right and saw Belinda under the transparent cowl of a telephone nook. She turned and saw me, spoke a further few hurried words, put the receiver down and strode towards me. I held my ground, hoping she was not annoyed with me; to my relief, she wasn't, but she was brisk.

“We can make a move. Let's get going.”

If she was on my side, the last thing I ought to do was distract her or make any kind of trouble; that would be really stupid; so I did not ask, Whom are we going to meet? I gambled on putting all my trust in Belinda. I was feeling stronger every minute but I continued to play the part she appeared to wish me to play. With my right arm round her shoulders she took some of my weight, more than she needed to take, as we went out into the corridor and commenced our voyage towards the back entrance.

Fortunately the corridors were busy and I was not the only patient being escorted while clad in pyjamas and slippers. I noticed that Belinda steered me away from full-face encounters with anyone in a white coat. “Dr Alldred is all right,” she muttered, “despite his name, but we don't want to run into my immediate boss, Dr Stearne.”

“Is he well-named?” I muttered back.

She giggled, “In more ways than one! Anyhow, my excuse is, I don't think there's anything wrong with just giving you a breath or two of fresh air.”

I made no immediate comment. I was staring at a wall calendar with the red-circled date showing that today was two days after the battle. My need for that gulp of fresh air sharply increased. I peered wistfully ahead down the corridor. “How long can I stay out?”

“We'll see how it goes. Don't push it; I'm doing my best.” She sounded edgy too.

Reckless gratitude surged through me, and I blurted out, “I think you're wonderful.”

“I've known that for a long time. Now: here we are. It's a nice warm day so you should be all right as you are.” We went through two sets of double doors and emerged into the hotel's rear garden.

The lawn was cut into the Slope to form a level area that ended a hundred yards or so ahead of us in a wall of rock. It wasn't crowded; a few people were out strolling or sitting on benches among the flowers. Closer to us was an area scattered with round tables, each with central pole and sunshade, each surrounded by four or five chairs. None were in use at the moment – except one table where a man I recognized sat waiting for us: one of the older members of my company, who seemed to have survived unscathed.

I sat, the nurse on my left, the veteran on my right.

“Glad to see you're one of the lucky fifth, Terry.”

Terry Croale nodded solemnly. “Glad to see you likewise, Duncan. You're right: about eighty per cent of us bought it. See any of the rest?”

“Murena.”

“So…. he's now a captain without a company.”

I gazed around the peaceful garden. “I expect we're going to spend the rest of our lives saying to ourselves, 'Why me?'”

“Maybe some of us need to say it more than most.”

Belinda reached across me and put her hand on his. “Now please, Terry,” she began, while he gave me a speculative, calculating look.

“All right, love,” he said.

I guessed that Terry, who had a certain way with him, had influenced the nurse to arrange this meeting. They were in it together; but I also guessed that she had more to lose than he, if they were found out.

I asked him: “Were you by any chance a reporter, in civilian life?”

“If I were – if I am – don't worry that I'll quote you,” he smiled. “See – no pen in hand – not writing anything down – my notes are in my head; besides, visiting isn't forbidden and we can surely chat a bit. You're rather famous now, you know.” Again that calculating look. He went on: “So it's natural that I'm interested in how you feel about it all. This decapod business, I mean.” He paused again, and I kept my lip buttoned, and now he got to the point:

“Funny that you were able to do something no one else has ever managed to do.”

I scowled.

“Maybe that's not the only funny thing.” I glanced at the nurse as I spoke. “Maybe it's also funny how I develop a fever after having come through the battle with negligible injury. Funny how I woke up to find I'd missed a whole day.”

Belinda and Terry exchanged looks, so nonplussed by my remarks that I don't think they heard what my ears picked up just then: a voice some way off saying, there they are.

“Yeah,” mused Terry, “a fever and a missing day – maybe it all is a tiny bit strange.”

“Listen, you two: I follow orders,” Belinda declared. “I give the injections Dr Stearne tells me to give. I don't necessarily have to like it.”

Terry's eyes avoided hers. “Hm, well, I don't want to land you in the soup. Better go back – ” He broke off and froze.

My reaction was different: I gave a sudden start which must have looked comical to General Faraliew, who grinned as he sat down at our table.

His first words, however, were not addressed to me but to Terry and Belinda.

“Don't get up. Relax. I know what you two have been up to. And it doesn't matter.”

The four of us sat eyeing each other, the general's eyes twinkling, celebrating his control over the situation. In addition to his rank and his natural presence – he was a very tall, imposing man – he was now cloaked in the aura of victory, of prestige which I could sense fairly oozing from him. He was going to announce our fates – and Terry Croale, by contrast, would henceforth sit back, silent and stiff, his little initiative over. Terry's audacity had its limits. He wasn't going to tangle with Faraliew.

Which left me to carry the can; not that I even knew what “can” it was.

“Wemyss,” said the general, “I want your motive. Tell me what possessed you to have a go at taming that decapod monstrosity.”

“Er – well, sir – I just followed a mad train of thought. A string of hunches…. which suggested that I could make a contribution to the future defence of Topland.”

“Creditable,” said Faraliew, poker-faced. “Go on. I want to know why you, and not another, did it.”

“Among the entire Topland army I might well be the only man without a phobia against them…. the only man who could establish a rapport with one of them…. bring it back for study…. that's how my thinking went, sir.”

“Anything else?”

“Instinct told me that here was a specially intelligent mount, trained to carry officers.”

“The stripes on it?”

“Yes, sir, those mauve stripes. And it seemed already to have decided that I was suitable rider material. If I turned my back on it, rejected it, the opportunity might never recur.”

“So you went and tamed a Gonomong Finger. I shall now tell you, Wemyss, what I have done. When the report came to me from Colonel Reece, I understood that I had a hero on my hands, a tricky hero whose deed might inspire a wave of horror as well as admiration. You can imagine, can't you?” (I nodded. He nodded in synch, smiling.) “Yes. So, for your own good, and for my Army's peace of mind, I – er – used some influence on Dr Stearne.”

“Ah.”

“Ah. Feel any resentment? Tell me honestly.”

I thought of the “fever” and the day subtracted from my life. But then I also thought of all the kinds of trouble he might be trying to avoid, and that I also might have an interest in avoiding them.

“Honestly, sir, I suppose not – ”

“Cagey one, aren't you?” Faraliew leaned back and chuckled, in complete control. “Anyhow that extra day, with you k.o.'d, was just enough. I used the hero theme, and my publicity contacts, to circumvent the public phobia. Articles slanted just right – eh, Croale? – have appeared in the Bugle, the Neydian Times and so on, yesterday evening and this morning. Your status is now safely fixed.” He grinned once more. “You're looking twitchy again, Wemyss. What's the matter now?”

“Sir, if I had any chance of getting away with it, I'd have no objection to being built up as a hero. But…. sir, it's the problem for any impostor: what to do when the real one turns up? In my case, it's like this: real heroes do exist, and when I meet any I'll want to be able to look them in the eye.”

“Yes, it's hard, isn't it?” Faraliew was full of amused sympathy. “And the worst of it is, the status grows on you, and you grow into it, so that before too long you are expected to be a hero again.... Don't groan, Wemyss. Somebody has to do it.” Then he lifted his right hand to a chest pocket and undid the flap and extracted a grey metal object and placed it on the table in front of me. “Take that. It's yours, to wear in this afternoon's victory parade. Keep it switched on.”

It was a mobile phone. Cell phone, I named it American-style, with an uncanny pun on cell, as I touched it with a forefinger and experienced a little jolt of apprehension, in which I half expected ghostly prison bars to rise around me. I felt really spooked, but it was merely one of those overwhelming insights of mine which turn out to be a lot of rubbish. The only conclusion I obtained from it was that sometimes it can be a disadvantage to have read too much science fiction, especially the bit in Philip K Dick's Ubik where the guy learns he's dead when he sees a message scrawled on the wall of a urinal…. I had thought, for a shocking instant, that the mobile phone was an equally disconcerting message for me.

For to see one at close quarters at this late stage – after I had lived on this world for twelve weeks or more – seemed weird.

Faraliew, admittedly, had used one the day I first saw him. And in parks in Savaluk, during lunch breaks, I had seen a few executives with hand close to ear, though they might have been scratching their heads or adjusting their hats….

“Pick it up, Wemyss! It's not a grenade!”

“Sorry, sir.” I gave a weak laugh; my fingers closed round the thing. “The sight of it gave me the jim-jams for a moment,” I added as I tucked it into my shirt pocket.

“Why, may I ask?”

“Because, sir, I'm just a maladjusted oneiro.”

“I see. Well, in my opinion you have the virtues of your defects. And on that jolly note – ” He stood up; we rose likewise. “Captain Murena will give you the schedule for this afternoon.”

I could picture, at least vaguely, what was going to happen. Some kind of procession, lots of cheering; me no doubt receiving instructions over the mobile phone, as to what to do and when, just so it could all pan out nicely, and the people have their show, and it all reflect to the credit of the powers that be. And why not? A battle had been won. A vital, generation-saving battle. A victory parade would be a natural sequel to it.

As a parting shot Faraliew added, “You'd better get properly dressed, for a start! You need to look good, sauntering on Ydrad.”

“'Ydrad', sir?”

Faraliew quoted, “'Nothing did he dread, but ever was ydrad.'”

“Ah,” I said. It came back to me: the inscription below the sculpted form of General Necon Carredh….

“I see you got it, boy. Just to help you in your role as hero, I decided your decapod ought to have a powerful name.” In great good humour the General departed.

*

The nucleus of a crowd began to form as I rode Ydrad out of the hotel “corral”, and scores more people gathered to watch me direct my strange mount westwards along the main street of Volost. Following the captain's instructions I veered north-west to head for the main gate of the fortress city. The crowd drifted along with me, growing from scores to hundreds. Gesticulations and open mouths met my every glance, a multiform pressure that squeezed me into the role celebrity, while privately I pictured myself as a plodding fish-thing, fins partly evolved into legs, crawling up an underwater incline way back in Earth's Devonian period. According to this dreamy quirk I was headed for a shock on my first crawl towards the big surprise called shore, a drastic horizontal revelation which promised to burst upon me when a certain altitude had been reached – even though I told myself not to be silly, told myself that the only “surface” I was about to break was the jutting ledge of Neydio, a mere city-sized interruption in the natural Slope of Kroth. The urban ledge was bound to remind me of the out-of-date bias towards flatness, from which my soul had weaned itself.

I continued my oblique ascent, into an uninhabited area currently sunlit but over which, every afternoon, the crag of Neydio must cast a tremendous eastward shadow. No one would ever choose to build here. This bare region gave me a simplified view ahead. It was as though I were now merely climbing a grassy ramp towards the top of a cliff-like wall. Multitudes on foot streamed ahead of me, eager to get good places for the show.

Reaching the Spoing (the east-west railway that runs on a level with the join between City and Slope), I gave the silent order for Ydrad to turn due west. Now all I had to do was to follow the line, with the city's ordinary “built” wall, its modest-sized north wall, soon on my left – follow it till I came to the entrance station and the main gate.

The gate's double doors were wide open. I turned smartly left and rode through, and in doing so I rode off the Slope and onto the great platform city. At last I had entered Neydio, and for the first time in what seemed like ages I could see a level horizon of sorts – a couple of miles away.

The entrance square, overlooked by the gate towers, was flanked by lines of three-storey stone buildings, baroque style. The southern side of the square was open to the avenue that stretched away to that ersatz horizon, that edge, that drop. I reminded myself, that as I got closer to it I would have to view it more and more as just a nasty precipice. But here at the eastern end of Neydio, I could just about pretend I was back among the vistas of Savaluk, or even of Earth; an innocent pretence, not likely to undo my recent acclimatization to the natural sloping order of things. Sufficient merely to evoke a nostalgic smile.

The square had not yet filled up and there was room for me to let Ydrad lope around a bit as I admired the splendid sights of this end of the city. Some of the assembled burghers flinched as we sprang about and curvetted; others waved at me and I waved back. I heard shouts of encouragement and simple expressions of exhuberant optimism, on the theme of “Now we can show 'em!” They really were so glad that somebody had learned to ride a decapod…

At the start of the avenue itself a more disciplined body of figures was taking shape. The first few hundred soldiers were forming into companies. More were coming in through the gate; I had got here none too early. I looked around for Murena, in case there were orders for me. Bzzzzzzzz… The mobile! I slapped my pockets, found the phone, fumbled with it.

“Wemyss, this is General Faraliew. How are you doing – have you reached the city?”

“Yessir, I'm in the entrance square.”

“Payne from the Globe is waiting by the foot of the West Tower to have a word with you. Give the hack something to bite on, will you?”

“Right,” I said, unsure whether he had said “Payne” or “a pain” was waiting for me. I rode over to the Tower's steps and a woman with a bouffant platinum hair-do detached herself from the onlookers.

She approached to within a couple of yards and looked up at me. “Duncan the Fingerman!” she called out. “I'm Lucinda Payne from the Neydio Globe. Ever been here before?”

“Never.”

“What do you think of our city?”

“It was cruel of the builders to build it so big!”

She laughed appreciatively. “Does something to you, eh?

“Yep – nothing like it on Earth, that's for sure.” I mopped my brow. What had inclined me to use cruel? Corner-cutting, epigrammatic smart talk. Clever, also, to finish with the oneiro-style comment, “nothing like it on Earth”. The readership of the Globe would want an oneiro to sound like an oneiro…. must stay in character…. Quite suddenly I was mortally sick of being clever. Stabbed by a childish yearning, my inmost self wailed, I want to go home, but it was only a brief wail; my more adult self amended: Go home when you're finished, not before. Remember that sentence from The Lord of The Rings. 'The way back, if there is one, lies past the Mountain.' And what's my own Mount Doom? Probably upside-down.

Lucinda stepped back and waved her hand. “I'll catch up with you!” she called, while my phone went bzzzzzzzz-bzzzzzzz again.

“Murena's waiting to show you your place. There by the north-west plinth.”

“Right, sir,” I acknowledged, and turned my steed towards the captain some fifty yards away. I'll hang on – I promised myself in a moment of optimism – hang on and finish this parade, and then I can reasonably claim the reward of service: to leave the army, go home and lead a normal life.

I was weary of living by my wits, and this weariness had good sense behind it. I simply wasn't cut out for continual cleverness. I might sparkle for a while but the longer I stuck my neck out the more catastrophic the eventual let-down; just as for the grand avenue of Neydio the further the protuberance, the bigger the end drop, the precipice, must be.

Faraliew's voice crackled in my ear again:

“Remember to keep your phone switched on. And keep that reporter woman happy; I'd rather she followed you around… get me?”

“Understood, sir.” Now there, thought I, is a man who will never “go home”. Good luck to him, but I, having let him move me around like a piece on a chessboard, shall deserve some private life when the show's over….

I rode up to Murena. He stood in a courtyard, beside one of the groups of soldiers to be fed into the procession; I recognized a few faces, not many, in the group. Other groups had already begun their march down the avenue and Murena was keeping an eye on his watch for the right moment to tell us to join. I obeyed his instructions, positioning Ydrad on the indicated spot, and then had to wait a minute or so, facing into the late morning sunlight, a warm breeze buffeting my cheek. Forget about going home, whispered a sudden, unwelcome thought. The battle isn't really over, and the sagging sky awaits you.

Come off it, replied my intellect. The fighting is finished.

Don't you believe it, twitched my nerves.

“You next,” said Murena to me. “Off you go….”

I “wheeled” onto the avenue, entering my place in line. I, and those next to me, and the group of which we formed a part, became blended into the slow parade that stretched way ahead already half-way to the finish; crowds on either side waved and cheered all along our route down the great avenue of Neydio. Cheering with real enthusiasm: but of course I understood perfectly well that they were cheering an image, not the real me; they didn't know the real me, any more than I knew the real them; so it wasn't really personal. It was the skill of a propaganda department which, lucky for me, had managed to put a positive spin on what I had done – representing me in newspapers and in Army despatches as a hero. I strongly suspected that public opinion might have swung violently against me if left to itself; if people's minds had connected “Decapods – yuck – rider – yuck”, instead of “Decapod conquered, ridden, subjugated, hooray!”

Faraliew, bless him or curse him, had brought this about. And because he'd confessed his manipulation quite openly, even to the extent of naming the doctor whom he had somehow suborned into keeping me in hospital for an extra day for political reasons, he'd be all the harder to oppose. He was as good as saying to me, “Go ahead, try to make trouble for me if you want; I don't care a bit; I shall always be one step ahead of you.” Not that I wished to make trouble for him. It was just rather hard to accept all the cheers. They were well-meant and yet at the same time they were a pack of mysteries snapping at my heels and propelling me down an alley towards some destiny waiting to gulp me at the far end. To counter this sinister fancy, I straightened my back; I rode tall. Battle not over? Silly idea! Silly, at any rate, to fear a surprise attack. Faraliew must have seen to it that only a fraction of our Topland army, units chosen by lot, had been withdrawn to participate in this carnival of victory. The rest of the troops, plus reinforcements to make up for losses in the battle, guarded the Vallum as before, while the boulders of the Marraspang, winched back into start position, could if necessary be used again…. I took all this for granted as though I had read the General's mind. And all accounts agreed that the Gonomong, once beaten, stayed beaten for a long time. Even if, this time round, they were to possess a turner of tables, a Lee or a Rommel, such genius would have nothing to work on. There was no scope for them to effect a sudden military reversal. So what was I worried about? Our territory was saved. Yet inside me, along the pathways of my nervous system, obstinate doubts insisted upon waging guerrilla warfare against the occupying forces of common sense. Anxieties, beaten by the rules of logic, just as the Boers in 1900 had been beaten according to the ordinary rules of war, refused to lie down and surrender. So could I perhaps do a mental Kitchener and set up some kind of concentration camp system to starve out rebellious thoughts and give my head some peace? Trouble was, I couldn't get rid of the notion that links of some sort connected all the various mysteries swirling around me, threatening to unite into a grin that jeered, “Too late! You spotted me too late; I am the Hungry Horizon and I shall gulp you down.”

Very well, we'll see about that. Broad daylight, and the applause and good wishes of a friendly crowd, and my incredible good fortune in being uninjured and alive, easily pumped me with more moral energy than any bizarre fancy could suck away. I actually felt krunking good – unsettled, yes, but not depressed, no matter what skull-shaped doubts pestered my imagination. After what I had gone through it was hardly surprising that I should find it difficult to relax. So, find that doubt, that cranial lurker, and sock it. If you can't rise to an occasion while a whole crowd is cheering you, it's “a poor do” as my Aunt Reen would have said.

I was really impressed by the behaviour of that crowd. Whereas, on Earth, any similarly large and enthusiastic gathering would require a police presence, on Kroth it was not so. But if I were to state the reason for this difference – namely that Krothan people are sufficiently mature and self-controlled to express their good humour without any degeneration into yobdom – I would sound like a prig; so I won't say it. I'll merely point out that the reporter, Lucinda Payne, was able to run alongside the procession, in a gap between it and the crowd, a gap maintained by no fence or line of police but kept in being solely by the crowd’s self-restraint; and while she ran to catch me up, I noted other reporters running beside other selected marchers in front of me, and in no case did elements in the crowd follow their example. In other words there was no “if they're doing it, why shouldn't we?”

Lucinda, jogging at my side, turned her face up towards me. “Duncan!” she panted, “what's it like to triumph on Carredh Avenue?”

So that was what it was called. Not surprisingly, the road down the middle of Neydio had been named after the ancient hero of Topland. I sensed the civic pride in the reporter's voice. “Kind of it had to happen,” I shouted back.

She liked my answer. “Inevitability, eh?”

“That's it! We survivors have to end up here, in this awesome place!”

Of course that couldn't apply to all of us. For one thing it would be madness, while the enemy still lay within range of detection, to withdraw every man from the defences to throw a party. And in any case there couldn't have been room to parade the entire army. I hastily added, “Um… that’s to say, once we’d been chosen by lot…”

Except, of course, that my presence had not been left to chance.

Lucinda Payne was quick to point this out. “You tamed that Finger – you had to be here!”

“Makes sense to bring all trophies” – I slapped the decapod’s side – “here to our hugest fortress.” Remembering the General's instruction to keep the reporter happy, I was framing my answers as compliments to her city. And why not? I didn't have to pretend, I really was in awe of the place. To me, Neydio’s vast size strongly suggested it to be the legacy of some different civilization, maybe a past species, which possessed secrets of construction now lost; but that was not all: as I thought further I began to feel that despite its spooky grandeur and alien uniqueness, it fitted. Its location at Latitude 60, like the Topland boundary itself, was exactly where skis cease to be practical, where the influence of Topland culture thus reaches its natural southern limit. I gained confidence at having worked this out for myself. The achievement made me wonder if I might make more use of my talent for thinking things through in an unfamiliar world. Whoa there! Don't wobble too fast between wanting to go home and wanting more dizzying stuff. Keep your eye on the ball. The ball being – a new idea bouncing at me –

The rarity of mobile phones! And why was it high time I thought back to that? I sensed that it was an important train of thought. Rare rather than mass-produced, the phones yet existed in their small numbers. The infrastructure must also exist for them to work; imagine, all that arrangement for only a few phones! It could never happen on Earth. Link this with –

The maturity of the crowd lining this procession. The way they keep back without the need for police –

Restraint. That was the clue. I was getting answers. “Thus far and no further”. Restraint: a kind of power that Earth did not have. Allowing the diversion of effort into new channels –

I thought of the light-sabres, the laser swords used by the characters in the Star Wars films. That cute fictional idea that you can restrain a beam of light, make it go the length of a sword and no further – what power it would have, if that were possible! Light-sabres, ha! I almost literally licked my lips at such breaking of rules. It was my moment of understanding, my surge in appreciation of Krothan culture. Here human beings, like the illegal stop of the Jedi sword, might say “No” to mob psychology, and so might achieve things that were humanly impossible on Earth.

Earthly behaviour knew some restraint, of course, but always as part of a dismal trade-off. For example, on Earth you couldn't go all out for free enterprise, progress and social cohesion. Or liberty and equality. Or tradition and progress. Here on Kroth, well….

There's nobody to hear me, nobody to tell me I'm a prig: I can say the truth quietly to myself: here people aren't slobs.

Ahem. Harrumph. Quiet, now. Naughty, naughty. Mustn't judge people. Not even slobs? Shush! Who do you think you are, Duncan Wemyss? Hee hee, nobody can hear me…

Very much the guilty little boy, wondering when and how hard he's going to get smacked, I stared ahead as I rode, apprehensively watching the approach of the watch-towers and balloons which marked the southern, precipice-end of Neydio. The march was almost over and the procession was pooling into a magnificent square.

At its southern side reared the bulkiest of those buildings which must overlook the drop. The domed, columned pile had to be the Observatory, and the sight of its clean and stately frontage warmed my heart. Every citizen must sleep safer knowing the Observatory staff were there to monitor the great stretch of Slantland visible from that height, including, currently, the defeated and retreating Gonomong.

A figure in grey, I noticed, was standing close to Ydrad, much closer than people normally liked to come.

I peered down.

“Uncle! Typical!”

“Don't worry, the beast knows me. I didn't startle it.”

I was too startled myself to inquire into this. “I mean, typical of you to show up in such unpredictable fashion! Great that you're alive – yet I'm not surprised,” I added, my thoughts whizzing like midges, not only because of the joyous confirmation that I still had some family, but because Vic's presence anywhere usually fed additional power to the grinding wheels of purpose.

“Great to see you too, Mr Hero,” Vic remarked. “I am even less surprised than you – I knew for a fact that you were alive. We can talk later; you need to get down. I've come to take care of Ydrad while….” (I felt it coming) “….you're wanted in the Observatory. I gather His Nibs wants you to do one last job for him.”

This is what I get for my judgemental thoughts. One last job, eh?

*

An orderly took me along a carpeted corridor and into a lift. As he pressed a button for the lift to ascend, I thought: Electricity – that reminds me – I've never seen pylons on Kroth. So, are the National Grid power lines all laid underground? The expense, the effort! All that infrastructure for only some, not a lot of appliances! Again, restraint. That's the great secret. Capabilities taken so far and no further. Strengths are to be saved and not splurged. But saved for what?

The lift stopped; we emerged into an open-plan warren of desks and charts, where I followed the silent orderly past hunched and murmuring officials, till we reached a spiral metal staircase.

We clattered up this, into a quite different scene.

The “dome” was a half-dome only, as though its southern half had been sheared away. The two great telescopes were therefore open to the view over Slantland. They were mounted on a high bar, maybe fifty feet over our heads, and each tube was about four feet in diameter, angled down, aimed at the landscape to the south. One of them, as I craned my neck to watch, panned slowly. The other hung motionless.

During peacetime they were (I guessed) aimed at the sky, but once every generation or so, when the Gonomong attacked, the study of astronomy had to be abandoned, and the instruments swung to point downwards, at the southern Slope.

On the floor not far in front of me was a map table, and uniformed women with rods, Battle-of-Britain “Ops” room style, stood ready to shunt counters across it. However, this table-top was slanted thirty degrees, so the moveable symbols representing enemy units had to be magnetic.

The panning 'scope above our heads must, I realized, be remotely controlled; from its eyepiece the image which it had obtained was projected down onto the plotting table, in the form of a glowing circle which I could just about see from where I stood as it slowly crept across the map surface. If I were closer, doubtless I would be able to see if and when that projected image brought updated information. The women around the table were in a position to see, and to adjust the counters accordingly.

While watching, I witnessed one such adjustment: the operator reached over and gave a slight nudge to a little block the size of a decorative fridge magnet.

Voices sounded behind me, full of confidence.

“….And yet I say, the rider will be cloaked in that field.”

“Don't talk ROT, Brudenell!”

A third voice, that of the General, intervened blandly: “Major Whitton appears concerned that our theoretical discussions might result in an enlisted man being sent to his death.”

A dry snort. “Sending men to their deaths is a not unknown procedure in military circles.”

“Damn your cheek, Professor Brudenell,” said the Major. “You know perfectly well, there are deaths and deaths.”

“Er – I think,” Faraliew intervened again, “in fairness to the Professor, we need to recognize that he would be quite prepared to go himself, if it came to that.”

“Sir,” said Whitton, ignoring this, “I have work to do. Will you excuse me?” A moment later I saw the Major stalk past me, and as he went he muttered gruffly:

“Good luck, boy.”

In uncertain response, I half-raised, then lowered my arm, not having been given time to salute. Drat the man anyway – why couldn't he follow the wise Italian custom, whereby you don't wish someone good luck? For if you say “Good luck” to someone you imply that he's going to need it. And that need itself implies bad luck. I shrugged off my irritation and waited like a dutiful soldier, refraining from turning around, so as to avoid the suggestion that I had overheard. Seconds later came a touch on my sleeve.

Professor Brudenell turned out to be a small man who looked like a professor, a caricature of one, with beard and glasses and a bald dome surrounded by a straggly fringe of curly brown hair. His grab on my sleeve jerked me along; Faraliew, by contrast, beckoned courteously. I followed them until we came to a stop a few yards from the busy operations map.

“Look there, Wemyss,” the General muttered, “you see that concentration of the Gonomong….” and he pointed to one of the clusters of magnetic symbols on the slanting table, but then his tone wavered: “And by the way, Wemyss, I banked on slotting in a word with you before I have to go and make my speech…. there's so much to do. Come on, we'll use that office.” With me and the Professor in tow, he made for a doorway into one of the small, cluttered rooms on the edge of the main observation area.

Puzzled at his rambling tone, I sat where I was told to sit and waited to hear what this was all about. His words and manner implied a need for speed, yet he appeared less decisive than usual. It was as though he were seeking excuses for what he planned to ask. To my astonishment he began to discourse upon the strategy of the recent battle.

I did not retain everything that he said; nor (I was fairly sure) was I expected to; the important thing for me to do was to interpret his tone, and, when he got round to the point, be ready with the right response. It was a shock, all the same, when I did finally get the message: he was telling me that the Gonomong, though defeated, had taken quite a large number of prisoners.

Apparently the bird-borne unit I had seen in action had not been the only one. Others had penetrated much further behind our lines. At more than one point, a successful enemy raid had bagged a haul of civilian prisoners, destined for slavery in the steep lands of the far south.

Faraliew brooded: “If I had known…. but I did not know of their bird-men, any more than they knew of our Marraspang. You may wonder at the lack of intelligence on both sides. But this isn't Earth, Wemyss!”

I thought I had better contribute something.

“I get what you mean, sir – on Earth, espionage and the media saw to it that there weren't any great technological surprises in war. People knew more what to expect.”

“Precisely,” said the General, and emitted a disgusted sigh. “So you see, the great victor, yours truly, was caught napping. Yet in a few minutes this same great victor is going to have to make a rousing speech. A proud speech – the people all expect it – and how do I tell them about the cost? The horrendous wasteful cost?”

“Stop it, sir!” I said. His eyes went wide. But the point I suddenly had to make, because it was so central to my own experience in the battle, poured forth so urgently that both he and I overlooked my insubordinate tone. “This 'waste of war' stuff is so dangerous, sir! How can war not contain vast blundering waste? And so you fall into thinking, all right, I am prepared to risk death, provided it's meaningful, but not unnecessary death, no, not that – and there it is, the trap! It's a trap,” I babbled on, “because if you're disinclined to accept unnecessary meaningless death, you're going to be unable to fight at all. For there's no such thing as an efficient battle! So you reach the logical end of that train of thought. Desertion.”

“You've twigged, I see,” Faraliew said with a haggard smile. “You're in the know. And the way out of it?”

“Is to encourage the greatest fear, the fear of disgracing oneself. That's the only thing strong enough – ” I stopped. I couldn't understand why he was giving me all this time and attention.

“Duty, they call it,” said Faraliew. “The determination comes from inside you. I’m glad you’ve thought that far.”

What had I done? Into my brain came a thud of comprehension. Quite fairly I was caught in my own net.

Professor Brudenell, who had not spoken for a while, now exchanged glances with the General and said, “May I explain to him now?”

“Go on, Professor. But make it short.”

“Sure – sure – no need to make a meal of it. Just to explain to him what he’s volunteered for. Wemyss, does the name Nathan Salterius mean anything to you?”

It did ring a vague bell. “Some legend of the Army….” I forced myself to concentrate, to accept I was in for it.

Brudenell continued:

“Nathan Salterius, during the Rip-Mig before last, about twenty-two thousand days ago, was captured by the Gonomong. So were many others, but he was the only one to escape. Stories vary as to what happened, but the main point is, while he and his captor were riding a decapod, something happened to his captor, and Nate found himself riding that beast alone. Plenty of others surrounded him not far off – and yet he managed to make his way back to our lines. The question is, how did he avoid being seen and recaptured? My theory, which is consistent with what else we know of Gonomong psychology, is that any decapod-plus-rider combination is subsumed as a gestalt – ”

Faraliew interrupted, “Put in layman's language, Wemyss, what the Professor is trying to say is this. If you ride a Gonomong steed, you are effectively disguised as a Gonomong, simply because you are doing something which only Gonomong are supposed to do. This should hold true provided you don't get really close, for example within touching distance. So with any luck and a reasonable degree of caution, your mission enters the realm of the possible.”

Ah yes, my mission. Faraliew was doing his duty, after all, by squeezing the best out of me, so the least I could do was to allow myself to be volunteered.

He unrolled an annotated paper map and spread it before me on the desk. “We don't have a lot of time,” he remarked. “The behaviour of the Gonomong is staying true to pattern. At the end of their last great ripple migration, they paused some miles down-Slope and made an encampment in which they sorted themselves out before accelerating their retreat south, and it seems they are doing the same this time. Their captives are there…. somewhere. We could do to know exactly where. I expect you can guess what I'm going to ask you to do.”

“I'm to scout on Ydrad,” I said. “Find where the prisoners are being herded. Bring back information to be used in planning a rescue raid.” I heard my own words cold and clear; I saw him nod; and then more words came out of me, with a coolness which mildly surprised us both. “Before I go,” I continued, “I should like to say goodbye to someone, if it can be arranged.”

He lifted his brows. “Of course. Within reason. That is, if the person can be fetched in time. Who is it?”

“She is an army nurse, Elaine Swinton by name. I don't know where she is. I've asked around but I don't seem to get anywhere.”

“I'll get someone to check on it. Meanwhile, you study this map while I go and make my speech,” and he gave me a pat on the shoulder and left the room. The Professor remained sitting quietly, in case I had questions.

The map, and the notes, made the outline of the mission fairly plain. The information had obviously been derived from the main map on the plotting table. It showed the concentrations of Gonomong, and some question marks in red showed possible locations where prisoners might be kept.

“Not much time,” I muttered. It was easy to imagine the captives falling away in the clutches of a personified Gravity dragging them down, away and down beyond help…

Professor Brudenell spoke:

“You're not the only oneiro in the Topland army, and Ydrad is not the only decapod left behind by the Gonomong; others have been spotted wandering and grazing in the groves and clearings of the frontier zone.”

I looked across the table at him. “So – one of the Army's tasks in the days ahead will be to forge a new reconnaissance corps from this material?”

“I believe that is the General's idea,” agreed the Professor. His voice was as quietly objective as mine. We were both pieces that had been moved into our places by a grandmaster. “Meanwhile you are to be a pioneer, for you and Ydrad are available now.”

It was now that the Battle of Neydio was really over for me. The last shots had been fired of that battle within myself. No doubts remained as to the next chapter in my life, though I experienced a presentiment that its path was going to be very much longer. No matter what Faraliew realised or intended, no matter how great the General's skill in manipulating his human resources, the real force came from the unveiling, clarifying, hungry horizon. Duncan Wemyss, responsible, patriotic citizen, shrugged and admitted: I must do it.

For in addition to the citizen there is Duncan Wemyss the sinner, the prig with his gloating over the poor yobs and slobs of Earth, which has left an unsavoury taste in his mouth, so that he needs to punish or at least purge himself, by risking his life for others.

Finally, weightier by far than Duncan the citizen and Duncan the sinner was Duncan the pilot, the steersman of self.

The stormy events he's been through have created a matching force inside him, a determination to push back against the pressure, to equalize within and without. Maybe he’ll adjust to peace again when he’s a much bigger man, but for the moment he can no more retreat from unfinished adventure than a deep-sea diver on Earth could safely bob straight up to the surface. Equalize the pressure or get the bends!

The minutes had gone by, and suddenly Faraliew was back after having made his broadcast. “Phew,” he said, “you did well to miss my ramblings (wish I could have). Now, Wemyss, as to your girlfriend….” His tone became gentle as he placed a list of names in front of me. “Missing persons, presumed captured by the Gonomong. Here….” and he put his finger on an entry near the end.

I read her name, and my throat went dry. “Thank you, sir,” I mumbled, “for getting the information.”

He said quietly: “It does look as though you have an extra motive to locate those prisoners.”

*

Preparations went ahead during most of the rest of that afternoon. A set of saddle-bags was shaped to fit on Ydrad, and they were filled with such provisions and survival equipment as the Army experts thought suitable for a reconnaissance lasting many weeks, though it was hoped that I would return within a day or two. I, personally, had no doubt that the experts were far too optimistic, but I didn't bother to say so. Discussion might mean delay, and what was the point? Commitment – that decisive thunk of the guillotine that chops the past away from the present – left me willing to dispense with further talk.

I only saw the General again briefly, before I left the Observatory building. “Just one thing, Wemyss,” he added as he bustled by. “Some concern has been expressed about the way that steed stayed behind for you. Almost as though the thing were arranged.”

I shrugged, “It's only a dumb beast, sir.”

“A dumb beast trained by its owners.”

Well, of course it was trained. Just as a warhorse is. I went on listening to what Faraliew was saying, but I did not concern myself with his meaning.

“And it's a special one,” he went on. “We can't see how it would profit them to plant it on purpose amongst us; quite the contrary, but we're taking as few chances as we can. Checks and balances – that's the way to proceed. You're to have a companion for your mission.”

“I'm relieved to hear that, sir.”

“A mounted companion, of course. We have managed to round up another decapod, one of the few strays left over from another part of the battle line. And we have found a rider for it: someone who, like yourself, lacks the normal Toplander's antipathy for the creatures.”

“Another oneiro?” I asked, smiling.

“In a manner of speaking, yes. Someone who's Earth memory and Kroth memory are balanced and equal….”

Faraliew's rather elliptical pronouncements caused my smile to broaden into a laugh. “You couldn't keep him out of it, could you, sir?” A lazy side of me rejoiced that I would be able to abandon responsibility for leadership of my mission.

*

Unbelievable, that I could laugh. The trusting mood I was in. Life doesn't always punish you for your faults.

My fault then was that what with my delight at being reunited with my uncle, and relief at the thought that he would run the show, I took him for granted; I did not stop to think that his life would be put at risk the same as mine. It was as though I could not doubt his invulnerability; no more than a toddler, being taken to play on the beach with his parents, will think to fear for their safety.

Departure was set for after nightfall. We left Neydio and rode back down to the frontier. The motionless stars of the Krothan universe, and the lights on the summit of the Vallum behind us, looked down on two giant inchworm-like steeds, Ydrad and its companion which was called Gnarre, which began to stalk southward into the unknown, each sure-footed in the dark; Vic and I were able to ride sufficiently close together to communicate in voices barely above a whisper.

“We skirt that wood,” I said when a blob of deeper darkness loomed ahead, and so saying I steered to the left, to find that we were continuing amongst vague crouching forms that blackened the dimness. I shone my faint red torch on the map I carried. “Over here,” I said, altering course again. “The first recommended stop.” I didn't mind giving the obvious orders. Vic could take over when things got complicated.

In what I guessed was a glade about two miles south of the Vallum we halted to wait out the night. Tomorrow would show whether Professor Brudenell's theory was correct, that we were sufficiently disguised to spy out the encampments of the Gonomong.