kroth: the slant

4: the slope

After a dream like that it would not have surprised me if I had found myself on the floor. But, though the duvet was twisted and askew, showing that I had thrashed about, I hadn't actually got as far as falling out of bed. Maybe I missed a chance there; maybe the bump, if I had fallen, would have woken me sooner.

My pyjamas were drenched with sweat, and in some disgust I lurched in the direction of the shower. I had taken maybe three strides when I stumbled against an object that had not been there before – a bathtub. No shower? No shower. Come to that, all the rooms of the suite impressed me vaguely as being smaller and simpler than I had remembered them.

Aha – so ran my thought – I am not awake after all; this must be one of those con-dreams where you think at first that you've woken and then you find you haven't. And if you try to wake up you just find yourself in yet another layer of dream. In these tiresome situations the only thing to do is to wait for the natural vigour of body and brain to break one's self out of the pesky illusion.

Meanwhile, though, I threw off the sweaty pyjamas and bathed in the tub, ignoring the yapping inner voices that told me I would not need to do this if I were still in a dream; that I was therefore not in a dream; that something had gone frighteningly wrong.

I got dressed. Noting that my possessions were still around, including humdrum things like my toothbrush and a copy of the Radio Times, which oozed all the reassurance of dullness, I became quite cheerful on the surface of my mind. Next stop: a nice dream breakfast! But wait! I hadn't opened the curtains. Opening curtains is a natural reflex to the start of a new day. To glance at the weather – a normal thing to do. So, why not?

As I hesitated, I heard the silence. No continuous growl of London traffic. In which case, maybe the window was not such an inviting prospect after all. Maybe it would provide me not with a first-floor view over part of South Kensington but with a view of something else, something I'd rather not see. So maybe I should forget the window and just go out through the door, which should only take me into one of the corridors of the hotel.

It's quite natural, in a dream, for one's analytical side to take a back seat; thus I contrived to hope that although my room had changed, the rest of the building would be the same, and I could stay in it until.... until the outside became acceptable. Better still, why not restrict myself entirely to this room, for a while? It was bearable, and – it would be stupid to face the corridor now. Better tackle it when it's in a better mood. This was dream-logic with its emotional laws.... and yet once I had my hand on the doorknob, suddenly it was all no use. My realistic self simply took over, and in sticky slow motion I could not retract my turn of the knob, the command from my brain, posted into the system of my nerves, wending its way towards delivery, was unstoppable, and while the timid side of me kept bleating that I should have stayed in bed, the door began to open under the pressure of my hand.

The first inch of opening let in a shaft of direct sunlight. In some hard and precise way, from the intrusion of that light I knew that I was awake: the long run of denial was over.

I pushed the door fully open.

Here are the facts of what I saw.

I was facing out from the front porch of a bungalow. The house appeared to be surrounded by the ingredients of some ordinary English suburb or village. My front garden had roses, irises (a bit late for irises, I thought), and a well-kept lawn; the concrete path ran out to a gate in a privet hedge. Through the bars of the gate I glimpsed a pavement and kerb. Beyond, a half-visible motorcycle leaned against a tree on the other side of the road. The street was lined with detached bungalows similar to mine, all built on a hillside, sloping quite steeply upwards to my left. The road climbed the slope, curving gradually back towards the rear of my house as it did so in order to skirt a pine-wood, while to my right, on the down-slope, my view was obstructed by some tall oak trees belonging to my neighbour. From where I stood on the front step I could not yet see people, but my ears caught a distant trace of ordinary voices.

Yes, I knew I was awake. But how did I know? First of all, the scene was so crisp. Its sheer hardness and clarity obliterated all thought of dream.

But secondly, and more powerfully, for the sake of survival I knew I must cut out the fooling. A trick, a big trick had been pulled and I must take it seriously. A shock was impending and I must brace myself for it. The most dangerous strategy of all would be to accept the all-round pleasantness of the scene at face value, for only a mug would be optimistic after having found himself transferred during the night to an unfamiliar location with no explanation as to how or why he had been taken there.

What gave me a really bad feeling, was the strong hunch that what had been done to me was not a crime in any normal sense of the word. A foreboding of something worse than crime, worse even than spooky, pawed at the threshold of my understanding as I nerved myself to take a step forward.

This peculiar fear, that hampered my movement like a river of mud, was of a kind I had never before experienced or even heard of. Until then, if anyone had asked me what is the worst kind of fear, I would unhesitatingly have answered, “supernatural terror – of ogres, vampires, things that go bump in the night”. I now know that there is another dread which can out-match it. Call it universal fear. All other horrors seem mere drama when the stage itself starts to tip.

You may wonder what I mean; but, if ever you meet that outrageous geographical terror you will recognize it as the ultimate emergency. Then for the sake of survival you will be forced to apply dream logic to a waking nightmare. I, at any rate, knew “in my bones” perfectly well what I would find when I reached the gate… I had yet to admit it consciously, but I knew.

To get it over with, I walked down the path, and, nearing the gate, I began to see some people on the pavements: a few pedestrians, someone entering a corner shop, a woman with a child in a pushchair pausing outside a hairdresser's. Even with my senses keyed to a high pitch I could detect nothing unhealthy or weird about their faces or their movements, but I did consider that they appeared to be rather subdued, as though bad news had just been announced over the radio, and a frivolous part of me wondered if in this dimension England had just been knocked out of the World Cup yet again. It's a marvel how the brain can babble away with its stupid chatter even in the face of the most appalling truth.

I reached the gate, opened it and stepped onto the pavement. I gazed to my right, down the road. From the eerie clarity of my distance vision I might have been on an airless world like the Moon, despite the plentiful signs of life and the blue sky and the fact that I could breathe. Let blunt language now suffice for what I saw.

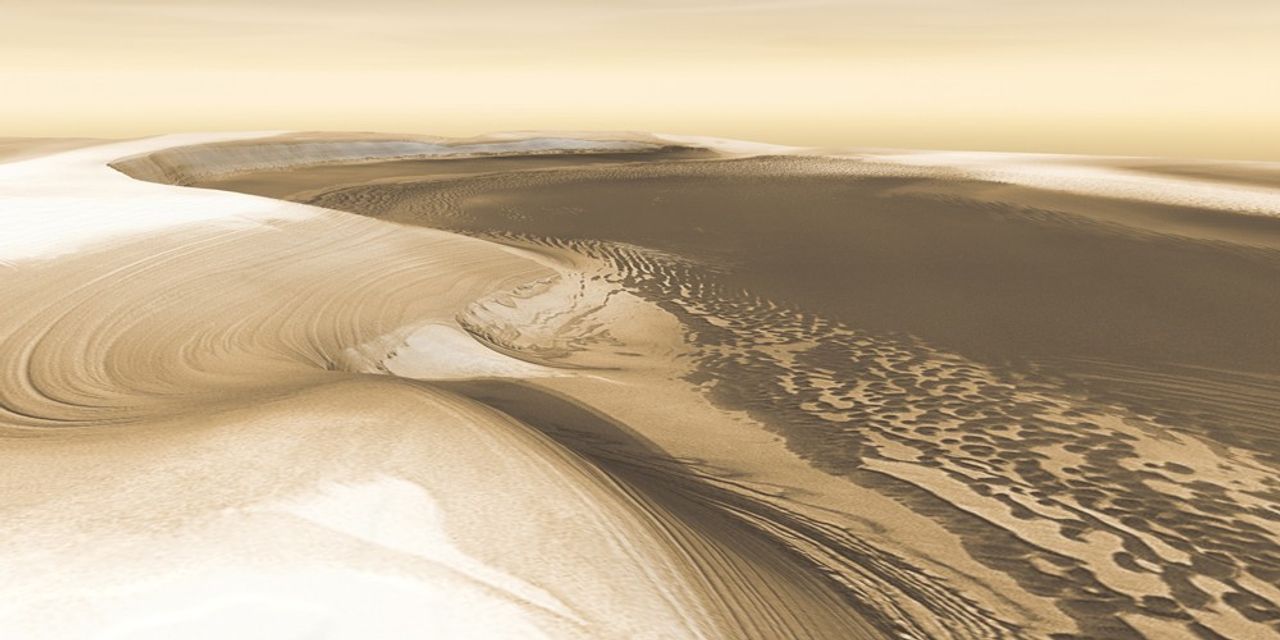

The whole world was tilted about fifteen degrees to the horizontal. Down-slope the sky, un-obscured by cloud or haze, reached all the way down to fifteen degrees below where the horizon ought to be, and thus showed that the slope descended forever into the blue.

I averted my eyes and shivered, shivered again, and, convulsed with vertigo, slumped against the gate-post. Run back into the house, I urged myself, and sleep it off; I must have been drugged! Not unheard of, surely, a drug that plays tricks on the eye? That has got to be the explanation.

But my house, and all the other houses, were bad news as far as this drug theory was concerned. For when I say the world was tilted, I don't mean that a normal horizontal scene had just been tipped over fifteen degrees. The houses did not stand perpendicular to the slope, which they would have done had that been the case; instead they were sensibly built to compensate for the slope, to make their floors level, which was why I had not known of the tilt while I was still inside. In other words the houses stood just as they would have stood on a hill on Earth, only this hill went on forever. If you stayed indoors with the curtains shut, you could hide from the truth, but outside there was no escaping it, no disbelieving.

Turning my back I took the opposite direction and began to plod along the pavement up-slope. This upward forever-tilt, though creepy enough, did not have the down-direction’s awful sagged horizon.

Don't get lost, I warned myself. When you've finished your walk you'll want to be back at your house. Well then, if you just keep left you'll manage to do that easily, you'll just go round the block. But that means you'll have to face the down-slope on your way back. Well, so what? You can get used to it. You better had.

The road, as it veered gradually leftwards to skirt the pine-wood, came at length to a sharper corner, with a house on the corner-plot. It had the look of a new-built house. I noticed one window with Venetian blinds pulled down and another blank without curtains. The garden was bare earth. It had no hedge or boundary wall. I jumped to the conclusion that the place was uninhabited, and I suddenly wanted, for some emotional reason, to feel that bare earth under my shoes. So I trespassed; I cut across.

Certainly during those moments I was in a state of bewilderment, under the mental bombardment of my delayed reactions to fantastic events, and this must be why I set out to do something so incautious as to walk over that garden.

“Corn salad! C-o-o-o-rn sallud!”

The scratchy voice made me jump. Freeze. Gulp. Then slowly turn around.

“You're treading on my c-o-o-rn sallud!” insisted the owner of the voice, a very short lady in her fifties, with bright snappy eyes and an underslung jaw that made her upper lip protrude. Embarrassed by her crossness I felt natural shame at having stepped on ground which someone had planted and in which, I now noticed as I looked down, some seedlings were pushing up.

“I'm very sorry,” I mumbled, and stood confusedly wondering in which direction to step. “I'll pay for the damage....”

“Hey, young man, are you all right? Come here!”

I obeyed. She was looking hard at my face.

In a softer voice than before she said, “Don't worry, it's all right. You look as though you could do to sit down. Wipe your shoes properly, there now, good lad. Come into the lounge. Take a seat.” I accepted gratefully.

We faced each other in armchairs in a partly furnished sitting room. The windows lacked curtains; she must have just moved in or maybe the curtains had been taken down to be washed. “You live just down the road, don't you? I am Miss Tyler.”

“I'm Duncan. Duncan Wemyss.”

“Of course, I remember. Duncan, I admit I was rather irritable just now, but I suppose, looking at you, that you had a worse awakening than most of us did.”

I sat up straighter. “Awakening?”

Miss Tyler said gently, “From the dream of Earth.”

I slumped. She went on, “You poor boy, have I shocked you? I suppose I am rather blunt. Some people can't stand it being mentioned directly. I saw Celia Hammond early this morning – she's next door to me – putting out her wheelie bin the same time as I was, and I said, 'snap!', meaning to congratulate both of us on our promptness, and when she just glared, I said to myself, I'm not having this, and so I added firmly, 'So we both coped, that's good, isn't it, Celia?' and she gave me a look, a really resentful look.”

“The dream of Earth,” I repeated in a strangled gasp.

“You see,” she approved, “that is a good sign, that you can manage to get the words out all right. No sense in repressing these things. As long as you keep the memory in its proper place and don't let it become an obsession, it's good to.... Duncan! Yoo hoo! I say, do you want me to fetch a doctor?”

“Doctor?” I echoed, slack-jawed.

“Dr Hatton might do you some good but I don't know if I could get him; there must be plenty of calls for his attention at the moment. You won't be the only one who is finding it hard to adjust to finding yourself back on Kroth. But since you're young it shouldn't....”

“I'll be all right,” I said hastily. The message had sunk in, from this lady's ramblings, that everybody was in the same boat, but that some of us were taking it better than others. I loathed the idea of being one of the weaker sort. “Uh.... I'm still a bit groggy, that's all. Kroth is....”

“The world.”

“Ah. Of course. Thank you, Miss Tyler. Well, I'll pop off now. Thank you for your kindness. I just need to find my way around.”

“Drop in any time.”

“I will. You're right, I haven't adjusted as well as most; I need all the friends I can get, but at the end of the day it's down to me to, er, adjust. Anyhow, I shall do my best.”

“Goodbye for now,” she said. “And welcome back to the real world.”

*

The next corner of the “block” turned out to be a crossroads, a very wide crossroads in the middle of which stood a stone “island”. Dominating the “island” was a structure like that of a four-branched market cross. A sign placed on top of it said, in letters big enough for me to read without going any closer, GUTHTIN - 75° NORTH.

Near to hand, on the corner next to me, stood a shop with a sign, GUTHTIN NEWSAGENT AND GENERAL STORES. I lingered in front of it, attracted by the idea of going in. For one thing it would postpone going round the corner and facing that awful dip in the sky gouged out of where the horizon ought to be. Furthermore, it made sense to buy a newspaper; it might tell me a lot. That raised the question of whether I had any money. For the first time on Kroth, I thought of looking in my pocket wallet.

Standing on the pavement outside the shop, I opened the wallet and took out a coin.

It was about the size and shape of a British pound coin. One face had two concentric circles and YEYLD engraved three times around the area close to the rim. The other face had a finely detailed picture of a fountain soaring above a city, both topped by an arc forming the name SAVALUK. Underneath the city was the coin's value: ONE TESG.

I rummaged for other coins and found some thinner ones – seven ONE MYNINU pieces, three SIX MYNINU and two EIGHTEEN MYNINU. From the most likely common multiple of these numbers I suspected that there were thirty-six myninu to the tesg, but I couldn't yet be certain. It struck me that I might learn quite a bit about this society from its coins, just as numismatists study the Roman Empire, and in my state of general shock I welcomed the thought of such scholarly discipline, its close boundaries, its defined limits…. The pictures on the smaller coins were as intriguing as the design on the one-tesg piece. One looked like a representation of a hill with rays coming out of it or spears stabbing down at it, I wasn't sure which. Another portrayed a city built on a thirty-degree slope, with a huge fortress wall facing the downward side. Then I realized that in playing guessing games with all this I was merely finding an excuse for inaction. It wasn't a matter of looking for clues about a vanished culture; I was in the midst of a living society, and surely I could pluck up the courage to enter a shop.

A bell klinged as I pushed open the door and went in. The sound of that bell, unexpectedly normal though it was, and though I liked it, gave my confused self a case of the jitters. I was glad no one was there to witness my cringe. I got myself in hand and focused my gaze on the news-rack. On its top shelf was printed SAVALUK TIMES, and on the lower shelf GUTHTIN GAZETTE, but both shelves were empty.

The sound of footsteps brought my glance back to the counter behind which there now appeared a dumpy, slab-cheeked woman in her sixties. This sight gave me the further shock of meeting someone I actually knew. “Mrs Nott!”

“How may I help you?” she said, frigidly. The old sourpuss gave absolutely no sign of recognizing me, but there was nothing spooky about this: it was just the way she had always behaved on Earth. She ran the corner shop in my part of Crickham and for years I had been a regular customer for her tinned groceries, light-bulbs and other convenience items and never had she given me a greeting or a smile. Her one role in the scheme of things, as far as I could ever tell, was to fill a vacancy for Grumpy Old Woman. So although, actually, I was glad to see her, I could not bring myself to say so.

“Er.... papers all sold out?” I ventured.

This turned out to be the wrong thing to say.

“Of course they aren't 'sold out',” she spluttered with typical contempt. “None were delivered! Did you imagine they'd be able to put out an edition today?” Her tone made it clear that I must be the stupidest dolt who ever lived.

Mrs Nott's hostility didn't bother me too much; in fact I would have felt more uneasy if she had changed her personality so as to be nice to me. Still, better not fan the flames of her ire. I therefore decided not to attempt any probing remarks about the big awakening; rather I would profit from Miss Tyler's experience with her neighbour Celia. So instead of saying something like, “Bad night, wasn't it, Mrs Nott?” or “Bit of a shock to say goodbye to Earth, wasn't it, Mrs Nott?”, I beat a retreat from the shop.

Now, if I was to keep to my idea of going round the block, it was time to face the down-slope stretch. Or if I wasn't going to do it, now was the time to chicken out. Except that there wasn't much point in chickening out unless I was prepared to continue up-slope forever, in which case I would never get back to my house, and would it not be rather silly to make myself homeless in addition to my other problems? Grimly I muttered, “What goes up must come down,” and rounded the corner.

From then on, along that stretch of pavement, I kept my eyes down, way down, and doubtless I must have looked a funny sight as I tottered along. The few other pedestrians seemed to take no notice of my difficulties. They knew, and I knew that they knew, of the great change from Earth to Kroth, and they doubtless understood, as Miss Tyler did, that it hit some people harder than others; at any rate they let me alone to work things out in my own way. Alternatively perhaps they just thought I was drunk.

Once or twice, since I could not always prevent my glance from straying forward, I did glimpse that awful sagging horizon, or rather – since you can't really call it a horizon if it's not horizontal - the bite taken out of where the horizon ought to have been. When this happened I squeezed my eyes tight shut for several moments. I couldn't take it, even though I did my best to argue myself out of the terror by comparing it with going on a space-walk. I had always loved the idea of being an astronaut, hadn't I? And you're even more surrounded by infinity when out in space, aren't you? So where's the difficulty? No use – the argument didn't work: my terror was not of space-on-all-sides; it was linked with the relation of ground and sky. Nor was I any more successful in parcelling it up with some science-fictional catch-phrase. True, part of my mind kept chattering on about alternate dimensions and what not, but it all came back to the soft thud of my shoes on that sloping pavement, and the requirement to concentrate, with bowed head, to avoid the blue stare of infinity ahead of me. All my efforts at making sense died away in that dizzying sag.

At length I rounded the third corner and now the down-slope was on my right, hidden for the most part by houses. I could breathe easily again except when I passed a school playground with its unwelcome openness.

Now the fourth corner – left turn again – up-slope once more – and I could hope I was plodding back towards my house. Having successfully got this far, I could dare to admit that there was delight as well as terror in this adventure. Whatever the reason behind it all, at least I could never complain that real life was humdrum. However, my stress-avoidance training reminded me not to get carried away. Play it cool! Walk that tightrope between excitement and fear! Now, was it really my house up ahead? Wow, I had done it! I had got round the block! My own little achievement. So appreciate it, Duncan, and take some deep breaths and be thankful you’re home.

I then noticed something else. The bungalow just before mine had its front door open. As I came further up, to the point where I had a full view of both my down-slope neighbour's house and mine, dream-logic reared up and whispered to me a comparison between these two houses and the two rooms which Vic had booked at the Rolvenden Hotel, London, Earth. That arrangement had been one room for him and one room for me. So, here, one house for him and one house for me? The pair of hotel rooms and the pair of bungalows might somehow be reflections, counterparts, of one another! In which case Uncle Vic and Aunt Reen might be in that next-door bungalow. At this very moment.

Looked at in one way, it was a daft hope. On the other hand if did turn out to be true, what a boon it would be to be reunited with real family! Besides, if anyone could be expected to explain what had happened, Vic was surely the one. And if I wasn't going to continue forever being forced to accept the crazy reality-flip from Earth to Kroth without any reason given for it, I had better find him, or someone like him. I could ask Miss Tyler, of course, but I feared to press the issue with her, and besides she probably didn't have Vic's extra helping of brains.

*

I stood in the doorway and knocked. No answer. I called out, “Excuse me-e-e!” No answer. I advanced into the hallway and knocked again, this time on the lounge door which was also wide open. “Excuse me-e-e! Hallo-o-o!” Borrowing some courage from somewhere I walked into the lounge.

Uncle Vic was lying on the divan.

It was obvious at a glance that he was not merely resting. He lay untidily as if he had collapsed or been pushed down; his face was frozen into an expression of slack dismay, his eyes wide open.

“No!” I cried out fiercely, rushing forward. Don't you dare be dead. I was right to clamp onto my denial of horror, for when I examined him closely I saw that he was, after all, breathing.

Had he been coshed or mugged by some intruder? Unlikely. It did not seem to be that sort of neighbourhood. If it were, my uncle would have had the sense to fasten the door. My guess, rather, was that when he had woken in this new reality he had immediately flung the door open and found that he could not face what he saw. It could have affected him worse than it did me: his greater intelligence could well have made him more open to the truth, and therefore more vulnerable to it, than I was. I could picture him staggering back and collapsing on the divan, his consciousness overwhelmed by the shock.

Anyhow, rather than stand around playing guessing games, my duty was to get help. Where was the phone? Come to think of it, what use would a phone be to me? I knew nothing about the emergency services in this dimension. What I needed was people. Helpful people. People who weren't like me; people who had woken properly, who had fully reverted to their identity as Krothans, rather than being stuck, as I was, with my memories of “the dream of Earth”.

Try next door. I ran out and down the path and turned right to the next bungalow down-slope. I ran up its path and knocked loudly and was about to knock again when I heard a woman's voice inside:

“Someone at the door, Elaine!”

My heart bounded to the joyful conclusion that this was dream logic working again, that the people I cared most about were thronging around me due to some kind of gravitational pull exerted by the emotions, and that therefore the name couldn't be coincidence: it had to be the Elaine!

The door opened and she stood there, tall and beautiful. Too tall and too blandly beautiful. My heart sank: this wasn't Elaine Dering. It was Elaine Swinton.

So much for dream-logic. The vapid, colourless, toothpaste-ad Elaine stood there like a mere pun on the girl I had hoped to see.

But at least it was someone I knew, if only by name and sight. And she certainly was a magnificent sight. From sleeveless white blouse and short tweed skirt her pale limbs radiated elegance; her face was lovely as ever despite its habitual blank look.

“Hello, Duncan,” she said with a trace of a frown. “What's up?”

“Sorry I knocked so loud. Look, it's my uncle – I need help for him – he's been taken ill – can you help me get a doctor?”

“Come in.” I followed her into her lounge. Her mother lay on a couch with her head propped up by cushions; she looked wan and feeble, and for a moment I wondered if the “end of the dream” had got to her in the way it had got to Vic. But no; she looked “normally” ill.

E.S. was speaking into the phone. Then she turned to me. “You're in luck; Dr Hatton is available. You can speak to him.”

“Thanks.” I took the receiver. “Doctor?”

“What can I do for you?” said a calm, reassuring male voice.

“I need you to come and see my uncle. He's collapsed.”

“The address?”

I turned to E.S. “What's the name of this road, Elaine? And the number?”

She raised her brows only slightly at this imbecile question.

“Kennan Road. We're at number 19, Mr Chandler is at 21, and you're living at number 23.”

“21 Kennan Road,” I said to the doctor. “Can you come? It's worrying. My uncle's eyes are open and staring but he's not conscious.”

“Is it a dream case?” the doctor asked. I guessed what he meant.

“Yes, I'd say it looks very much like a serious dream case.”

“I'll be there in a few minutes.” Click.

I thanked E.S. and her mother, and got up to go. E.S. said, “Hang on a moment. Mother, I'm going to see how Mr Chandler is.”

“All right, dear. I hope he gets well.”

“Elaine,” I said as we went out, “I really appreciate your support.”

“That's all right,” she shrugged. “It's not much trouble. It shouldn't be long to wait.”

We entered Vic's house, pulled up chairs and sat by the divan to keep watch on him till the doctor arrived. The conversation during those few minutes did not sparkle. E.S. sat with her hands in her lap and a patient expression on her face.

“How is your mother, Elaine?” I asked politely.

“She hasn't been well for some time, but considering she's so weak, she coped with last night quite well.”

As did you, I thought to myself. What an advantage it must be to have a mind like yours. The reality of Earth melts away in a single night and you remain quite unruffled, not even sufficiently impressed to give it more than a glancing mention. Talk about stress-avoidance! You're an admirable clod, Elaine Swinton. Perhaps I ought to become one too.

“I found it rather a shock,” I said dryly.

She nodded. “I thought you didn't look so good, Duncan. It wouldn't do you any harm to have a word with Doc Hatton on your own account.”

“Is he good?”

“Certainly he is. He's done a lot for mother. Our village is lucky to have him. Ah! This must be him.”

“Come in!” I shouted.

The doctor was a gently dignified man in a big flappy jacket adorned with biros; his voice and manner inspired trust from the moment that he bustled in. After an examination in which he tapped Vic lightly on the forehead, looked in his mouth and made passes over his eyes, he said: “Your uncle's condition is not dangerous, but it is serious in the sense that it needs to be seen to by the experts. He's in deep post-terrestrial fugue and I can't bring him out of it here. I have to refer such cases to Savaluk.”

“Who, what or where is Savaluk?” I asked, edgily. “Oh, sorry – ” for I had just remembered the name of the newspaper. “Savaluk is a place.”

Doc Hatton looked at me in surprise that turned to quiet pity. “Ah, so you're a case too.” He smiled, kindly. “Yes, Savaluk is a place.”

“Er, where is it?”

“You really don't know, do you?” Doc Hatton appraised me with professional interest.

“No, I don't!”

He said dryly, “It's at the North Pole. You can't miss it – the capital of the civilized world.”

“Oh,” I said in a small voice, not only miserable at my ignorance, but awe-struck at the hefty parcel of mind-boggling ideas which I would have to open and try on for size. For instance I had just learned that there was a Pole to this world, so the Slope didn't go on for ever, not towards the North anyhow, and what other huge things must I learn? I looked pleadingly at the doctor as the silence lengthened. “Well, I didn't know,” I said.

“No, you didn't, did you? But don't fret about it and don't sound so despondent. If your memories of Earth are strong enough to prevent you from recovering your knowledge of Kroth, well then, um….”

“Then it shows I'm retarded?” I interrupted, bitterly.

“No, it shows that you must have a special reason of your own to go in for this clinging to one set of data and rejection of the other. Tell me, have you recently undergone any – ah – particular therapy?”

I thought of my clever-clever techniques.

“I made a big thing of stress-avoidance,” I said. “Too big. It's led me to reject the real world.” What an idiot I felt, confessing this stuff within Elaine Swinton's hearing!

“Interesting, most interesting,” said the doctor. “You have a problem; but you can learn to get round it. In fact you may find your condition to be in some ways an asset. People are going to value someone with a really clear, sharp, well-preserved set of Earth memories. You'll get a lot of support, you'll see! And with regard to your uncle, no decent person will refuse help to a fugue case.... You two will lack for nothing on your journey to Savaluk.”

“How far is it, Doctor?”

“Just over a thousand miles.”

“What about the practical arrangements?”

“If you're wondering about an ambulance service, forget it – the Government can only afford that for cases where the illness is life-threatening. But transport shouldn't be a problem. Stand by the Royal Road and you'll hitch a lift pretty soon. The Royal Road,” he added before I could ask, “is the main North-South road. Go West for a couple of miles and you'll strike it; no trouble.”

“But how will I get Uncle there? He can't walk; he can't even sit up.”

Doc leaned over and gave Uncle's head a push, so that it lolled on his neck.

“Nah. He won't stay like this for long. Wait a couple of hours and I guarantee he'll be able to walk, and to look after himself to a limited extent - you won't have to nursemaid him round the house, though you'll certainly have to guide his steps outside. I suggest you set off tomorrow morning. I'll write you a note for the Royal Fountain Hospital at Savaluk.”

“But I'd better move in here for tonight, I suppose.”

Doc Hatton shook his head. “You'll see that won't be necessary.” He straightened, scribbled some words on a pad, tore the sheet off and gave it to me. “I must be off. As you can imagine, I have plenty of other patients today! Have a good journey and don't worry. Take it from me – you'll get help, support, guidance everywhere you go.”

“Well, thanks for coming, doctor.”

He went, and Elaine Swinton also got up to go. “So that's all right,” she said; “and I'll be getting back now.” Placidly as ever, her neighbourly duty done, she bade me farewell and glided off.

I waited for the doctor's prediction to come true. Mostly I sat in the lounge; occasionally I went from room to room. Vic apparently lived alone; I saw no sign that Reen inhabited the house. I wondered if in this world she had gone back to the Isle of Man like she wanted to do. Or rather, to some equivalent. Ridiculous; there couldn't be any islands, couldn't be any seas, on the Slope.... I tried to keep my wandering thoughts in order as I looked around for clues about this world of Kroth. I saw no radio or TV. I did find an old newspaper in the bin; I shook the potato peelings off it and spread it out on the kitchen board. The Savaluk Times turned out to be quite frustrating. Suggestive though its stories were, without a background knowledge of the culture and geography I could not make much sense of them. For example:

GALAST'S BLUFF CALLED

Ninghestund, .34:

The Galast of Hanamao in a speech yesterday declared he would consider the option of a tax strike if the empty seats in Parliament were not filled. A member of the audience, Li Zang, then asked him if that meant that the Galast would himself be willing to lead an expedition to Hudgung. The Galast replied, amid widespread laughter, that he was needed at home.

TV IN EVERY TOWN BY .00

Savaluk, .35:

A Government spokesman affirmed that the communications target for the dechemeron would be reached provided that no hitch developed in the Forty North Hydro Project. “We must remind the public that hydro power increases with the cosine of latitude, and that therefore the goal of 'A TV in every town hall' is dependent upon good relations with the Tribes of Forty. If they demand protection against the South, our commitment becomes open-ended.”

All as clear as mud. And the person whom I most relied on to explain things was in a state of “fugue”.

Daylight began to fade as evening drew on. I switched on the light – normal electric light. Performing this action, it came to me most clearly that a large part of the trouble with this new life was not its strangeness but its areas of persistent normality. I could have seen some sense in being pitched into a totally alien dimension, or into a human culture that had developed in its own completely separate direction, but what was I to make of Kroth with its impossible mixture of the familiar and the strange?

Whatever the answer was, I would not find it covered by my reading of science fiction. SF stood me in good stead insofar as it had given me a general elasticity of mind, but none of its standard props (alternate time-tracks, parallel universes, artificial dream-tests) were any good at providing me with an explanation of this particular set-up. I might have believed in any of them – were it not for the Slope.

I was thinking in circles. I wished something would happen. Something did – Uncle Vic stirred.

I stood up and called his name but he did not answer, nor did he so much as glance in my direction. Slowly he levered himself up and managed to stand, and then, shuffling like a zombie, made for the bathroom.

Minutes later I heard the toilet flush and then the tap run and then he appeared again, making for the kitchen. While I watched, he put the kettle on and with sure and careful movements began to make preparations for a snack.

There was a loud, confident knock on the front door.

I went to open and saw a very tall fellow standing casual and loose-limbed in a dark green sweater and corduroys. His face, tanned and bearded, was of a man about forty. He said, “Just thought I'd pop round and see if things are still all right. Elaine told me the doctor had been to see Vic.”

“You're her father? You're Mr Swinton?”

“Yes, Duncan.”

“Nice of you to come,” I forced myself to say, squirming more than ever at my lack of Krothan memory. “Do come in and see for yourself how he is.”

We went into the kitchen-diner and watched Vic tuck into a sandwich.

“He's like a sleepwalker,” I remarked, “which I suppose is not so bad – at least, on that level he seems to know what he's doing. Doc Hatton says it's safe to leave him for the night.”

“Then it must be so,” said Mr Swinton. He then turned to look me in the eye, and in a tone that was pleasantly self-assured he added: “I'd say that you are the one in the more difficult position. You're still stuck in the Earth dream, so I hear.”

“I suppose I am. That is – I'm not sure what to say – I mean, I know this is real, but....”

“But you don't remember any of it.”

“No. And why must I alone lack memory?” I wasn't being honest here; I knew the answer to my own question – I had brought it on myself. Stress-avoidance had led in my case to world-avoidance and to the state of inadequacy which I now suffered.

Mr Swinton answered, “Different people react in all sorts of ways for all sorts of reasons. I managed all right, but then I'm a businessman. Elaine's all right, but then, well, she's Elaine.” He smiled. “She always knew what she wanted.”

“Lucky girl,” I said. “What does she want?”

“To be a geologist,” he said. I was so astonished (and skeptical) that I didn't respond to this at all. He went on, “And do you know what you want, Duncan?”

“To get out of this mental fog,” I promptly replied. “To find my way. Uncle Vic used to tease me about teenagers; about how they all want to defy authority by being different, and how at the same time they want to do it by being the same as every other teenager. Well, I don't care about being different; I'm not defying anybody; I'm on the conformist side! I want to belong.”

Wow, I thought, that was quite a speech by me. Mr Swinton was the sort to induce one to confide.

He replied: “Looking at it from your point of view – you who know virtually nothing of Kroth – let me ask you this: how long would you say it should reasonably take, to get to know a world?”

I thought about it and then grinned sheepishly. “I suppose I am being a bit impatient.”

He nodded, his point made. “Things will sort themselves out.” He turned to go. “Drop round for dinner sometime....”

“Thanks, Mr Swinton.”

“And a game of chess too. I'll miss our games, while you're off on your jaunt to Savaluk.”

Hastily, to get his opinion, I remarked: “Doc Hatton expects Uncle and me to hitch a ride there.”

“Should be no problem. Well, I'll leave you to it.”

He went, and I was alone again – except for my zombie-like relative, who, after his brief supper, went off to bed. I stuck around for another half hour or so in the empty lounge, recalling all the voices – Miss Tyler's, Doc Hatton's, Mr Swinton's – who had told me not to worry and that things would sort themselves out. Then I drew the curtains of the lounge, and went to the front door. There was no key. I could not lock up behind me. Evidently this was a very safe neighbourhood. Another reason not to worry. I recalled the voices again, the reassuring voices of people I respected. But the first thing I saw as I stepped outside made me forget all reassurance.

It was a violet light winking at me from across the road. It shone between a chimney pot and a poplar tree. At first I took it to be artificial; a tiny bright lamp on a mast, perhaps. Then from its pointed brilliance I realized it was a star, but one that outshone even the planet Venus as seen from Earth, and its beauty prompted me to look for more, to crane my neck and admire, for the whole sky was ablaze with unfamiliar stars. All of them were telling me, by their brightness and colours and the patterns they made, that not only my old world but my old cosmos was something I must unlearn.

Sighing, with contradictory feelings of awe and complaint, I turned and plodded up the path to my house, went in, had a quick supper and went to bed. I had maybe seven hours' sleep, not too bad a total but it was punctuated – inevitably – by bouts of restlessness in which my imagination grated and churned like a malfunctioning cement-mixer. The hour came when I awoke and knew I was awake for keeps, so although it was still dark I got up and got dressed. I wanted to face that sky again. I wanted to see those stars again and somehow make friends with them in my mind; be reconciled with the universe in a way that was peaceful and certain. Stars, after all, are pure, clean things, symbolising all that is peaceful and beautiful and holy. You can't be led into nightmare by stars.

I stepped out onto the porch and immediately knew I had taken on too much. For there it was again, that violet star, low in the sky across the road, between that chimney pot and that poplar tree. This, I knew, could not be right. It could not be right but it was. And all the other stars in the sky are likewise in the same position, though most of the night has passed.

There was no end to un-learning.

The conclusion was inescapable.

This world does not turn.

>> 5: Northward