a brief history of ooranye

10: the vanadium era

[continued from 9: Nalre Zitpoidl and the Great Winter]

Character of the era

Era 23 was the longest by far of all the eras of Ooranye’s history up to the present. It lasted 55,391,027 of the Uranian 30-hour days, or 2,256.7 Uranian years, the equivalent of 189,565 Earth years – probably longer than the period during which homo sapiens sapiens has existed upon Earth.

Syoom itself was the arena almost entirely. There were few expeditions into Fyaym. In fact Fyaym was often forgotten, as though sfy-50 were the edge of the world. It might as well have been; for the four hundred million square miles of Syoom amply sufficed for the adventurous urges of a people reduced in numbers by the Great Winter and kept from increase by the waste of war and other conflict in this least intellectual and most swashbuckling of all eras.

Indeed there was little need for any challenging of Fyaym, at a time when Syoom seemed bigger, more chaotic and perilous than ever – its statistical definition hardly counting any more, so that for large parts of it we cannot even say if it still came under the old definition of Syoom. A lot more of it became forest; velng multiplied their huge mounds in the plains, sometimes holding humans captive for generations inside these artificial mountains. Abatis, planted for the protection of towns against various perils of the plains, themselves grew into dangerous ecosystems sometimes harbouring rogue states. Reformers and heroes punctuated the mediocrity of hereditary monarchies. The powers of Fyaym, looking on, discovered no threat to themselves, and perhaps encouraged the longevity of Era 23.

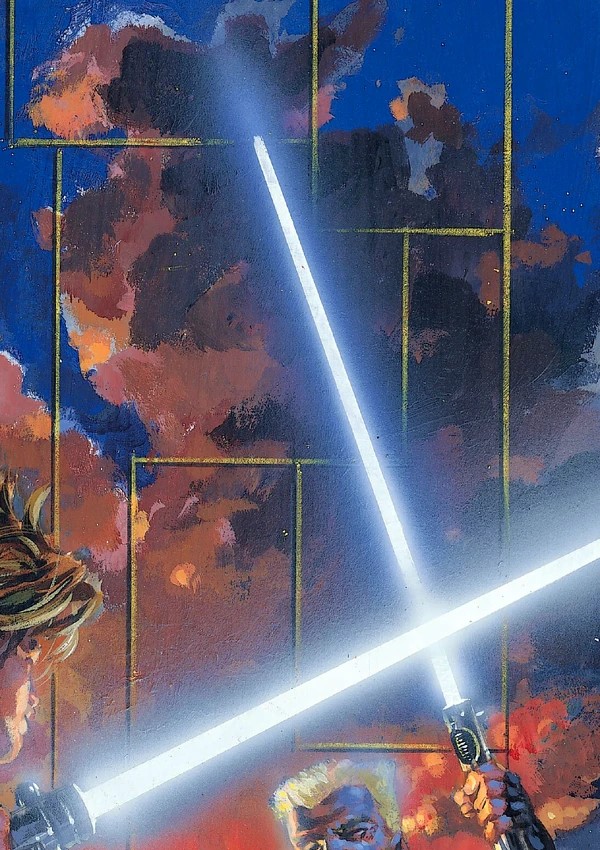

It was a golden age for the strong and the adventurous, the cheerful risk-taker and the soldier of fortune. No more colourful life could be lived, than that of a Wayfarer in Era 23. A Terrestrial teenager who has thrilled to the tales of Barsoom would naturally love to read about the Vanadium more than about any other period of Uranian history.

Yet it should not be dismissed as a mere adventure playground, for it was so vast in duration that almost everything set down in these paragraphs was contradicted at some point or other – thus occasionally rewarding the student of more subtle aspects of history.

Politics and Society

During the early days of this era, Nalre Zitpoidl was still alive. An old man, he wandered from city to city. Was he still Sunnoad? Or had one of the deposition ceremonies, which had been enacted during the Great Winter, been legal? If he had been deposed, this was one of only a handful of such cases in Uranian history.

Zitpoidl wrote his memoirs and, after showing them to a small number of personally selected readers, left them to be rediscovered and published many eras later. He alone had noted that the taharen had returned to Syoom, had looked the land over and had seen that there was no longer anything in its civilization for them to gain a purchase on – Man was now too simple to allow them to strike a deal with his racial unconscious; Man had ducked below such blows… This could be seen as Zitpoidl’s vindication, though few knew of it during his lifetime.

The uncertainty surrounding Zitpoidl’s status reflected upon the subsequent history of the sunnoadex in Era 23: the institution continued, but frequently passed many lifetimes in a state of reduced effectiveness, almost of abeyance. The Noad of a powerful city such as Vyanth or Ao or Pjourth might well possess more influence than the person who wore the golden cloak of Skyyon.

As has been noted, city-minds were reduced in awareness during the Great Winter. Their somnolence continued into Era 23. One of the effects this had on human society was that people had to drudge more. A kind of working class came into existence, to undertake many of the tasks which formerly the city-minds had willingly performed under the guidance of the “coaxer” professions: engineering and maintenance works; manufacture of tools, weapons, vehicles. A new labour-intensive culture developed. This gradually lead to yet more class distinctions as contrasts developed between skilled and unskilled labour, becoming intensified with the development of extremes of wealth and poverty – though no one ever became destitute in a Uranian city. Aristocracies of birth arose; after a while even hereditary monarchies – anathema to most ages of Uranian history – evolved in many cities. Dynastic selfishness led to the evil of war between cities. The final consequence of all this, as will be seen, was the downfall of the era’s culture, a downfall which originated in the creeping onset of the institution of slavery.

The

evils of war and (during the final fifth of the era) of slavery, were mitigated

by the fact of reincarnation. Out of the millions who lost their lives or their

freedom during this enormous span of time, almost all had another life left to live:

this is because the Vanadium Era was fairly early in Uranian history, and most of

its people knew that they were living the first of their two or three lives. The

most miserable of them could derive comfort from the certainty that they would get

another chance and a kinder fortune in some later age.