- Home

- Your Views

- Part ten of The Archives of the Moon

Part ten of The Archives of the Moon

by Robert Gibson

(Lancashire, England)

X

At this point, the narrative lost its smoothness and became agitated in style. Royden sensed the change immediately, assuming at first that it was an appropriate, if dramatic, match of style and content as the plot became tenser.

Yet it soon turned out to be more than this. Not only were the passions of Dzhaoo germane – the anxiety, the fear, the determination which must accompany the unparalleled flouting of all Yyr laws – but also the turbid obtrusion of the author had begun to stir the scene.

It was as if the unnamed writer of this document had become too impatient – now that the critical point was reached – to continue contently to let the tale speak for itself; under pressure from his own forceful opinions the Selenite author began to use the subliminal nuancing powers of the ultimate language to colour the story’s scenes with the extra coating of his passions.

Hence although as yet the reader as yet still had no idea as to what the protagonist meant to do, let alone what the result of his action would be, Royden nevertheless felt flooded with a loathing of that upstart, a yearning to brand Dhzaoo a traitor to Yyu.

Auctorial hindsight thus dominated Royden’s reading experience henceforth, overmastering him with the premonition that he was about to witness the end of Yyu’s Golden Age...

“Liucgk!” cried Dzhaoo, summoning a Uromian by name.

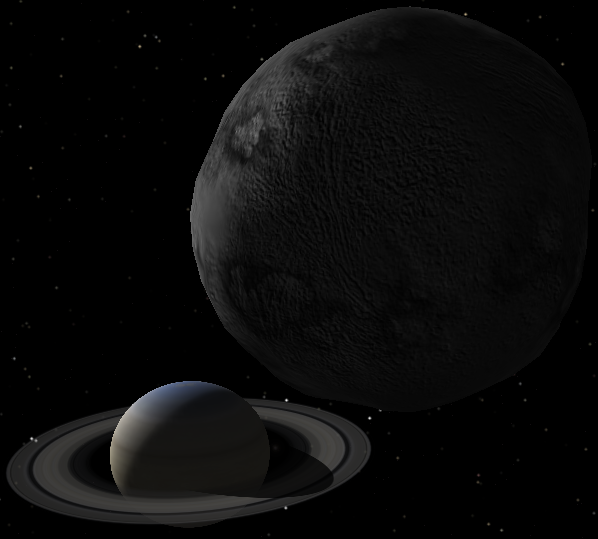

The word instantaneously traversed the quarter-million-mile void between the worlds.

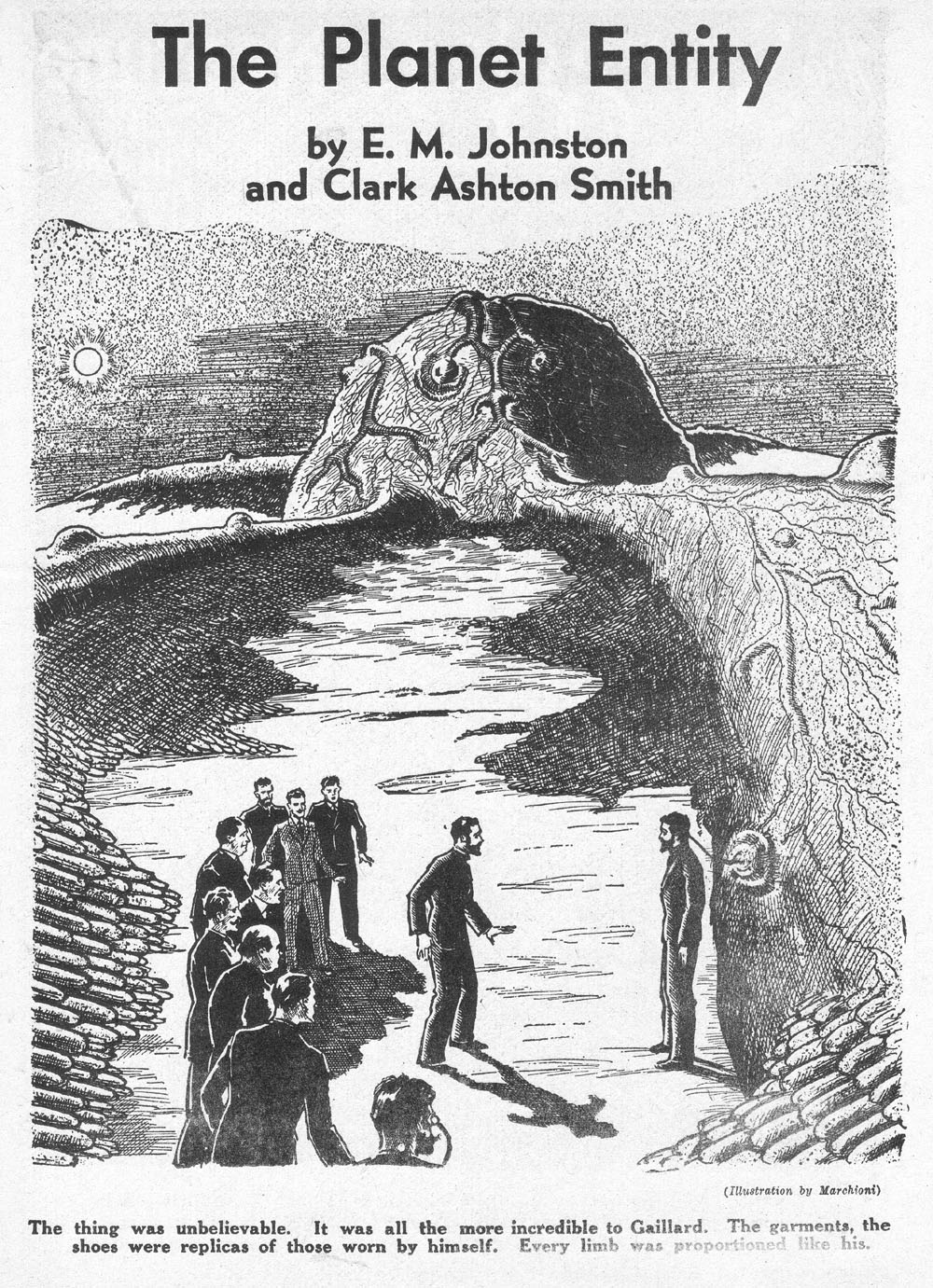

It issued forth from the vrell in the great temple at Xaxepp, one of many centres where, at this epoch in the history of the Solar System, a primitive Uromian humanoid race viewed the Yyr as gods.

“Liucgk!” repeated Dzhaoo, again summoning Xaxepp’s priest-king. “Prepare to receive the word of Atth the Many-Voiced One. Liucgk, Liucgk, the time of thy reward draws nigh. I, Atth, call thee that thou mayst hear my latest great command.”

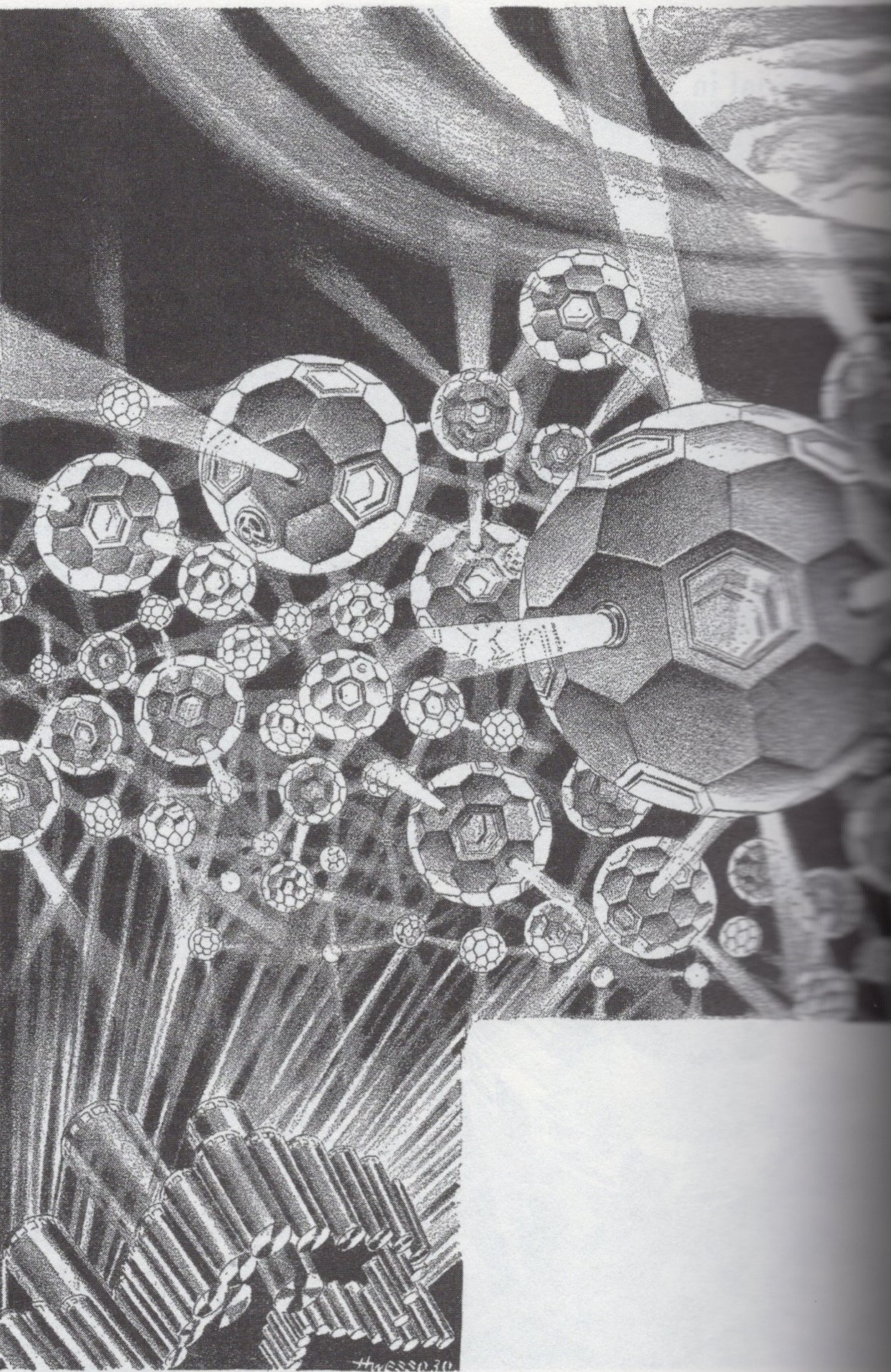

Having issued his summons, Dzhaoo paused to listen over the connection. He liked what he heard. Audible across the etheric void, the clangour in the temple at Xaxepp hinted at the throbbing of a power-house. It was the din of mighty engineries, chanting the cumbrous, mechanical rites of the gross-minded Uromians. He could imagine those hirsute, gigantic-boned primitives capering in bizarre attendance around their vrell, that was placed amidst their lurid industrial shrine, a hideous sanctum of metallic props and torrid fumes.

The din lessened slightly; presumably the words of the supposed god had caused the devotees to switch off some of their machines and prostrate themselves. There was then a delay of a couple of minutes, before Dzhaoo heard the harsh-voiced though awed reply of the priest-king of Xaxepp:

“O Atth, it is I, Liucgk, ready to hear thy will.”

The Uromian had replied in the language of Yyu, which he had taken pains to learn during his novitiate, though he could do no more than mangle the liquid vocables.

(Royden the reader, meanwhile, tried to rebel against the gathering spell of the story by asking himself: “How can there have been human beings on Earth before the age of the dinosaurs?” But the narrative answered him implicity. In the way it named and described the Uromians, it was obvious that although they were humanoid, they were not homo sapiens, nor connected by ancestry with that future species. The early Uromians were, in fact, an evolutionary dead end, doomed to extinction in the era which followed; their civilization would leave no trace. This was a good thing, hinted the narrative. They were spiritually deficient, lacking some spark in their souls; a false start in the evolution of their world...

But a force to be reckoned with in their own time.)

Dzhaoo announced: “Xaxepp’s hour is at hand. The moment has come for you to be given precedence among all the other cities of your world. That is the promised reward. It remains for you to ensure you get it.”

“O great god Atth! We are thine!” chanted Liucgk hoarsely. “Hast thou truly promised to bring us to victory over the evil city of Klapatt and its cruel god Palabaraz?”

“More than that,” cried Dzhaoo – and for Royden the narrative seemed to quiver and the sentences to contort as a signal that the protagonist was about to pass a point of no return.

For long ages it had amused the rulers of the swarms of Yyu to contact the brutish realms of Uruom via the telephonic vrells, and to choose protégés there, and to incite them against one another in a struggle for power which the Yyr rulers directed from their own world. Thus a heartless game of vicarious war continued and developed as a matter of prestige for the Yyr swarms.

Occasionally a moral voice protested; but no great incentive existed to end the abuse. With no actual travel between the worlds, the fortunes of war on Urom were of merely sporting interest to the rulers of Yyu, and could do no material harm to any of them.

Dzhaoo repeated: “More than that!” And now came the moment at which he ceased to play the game.