the open secret

a tale of the

strontium, yttrium and zirconium eras

from Uranian Gleams

by Robert gibson

acknowledgements to Fachtali Abderrah

acknowledgements to Fachtali Abderrah1: Public and Private

A flimsy base constructed of aluminium and plate glass, Sector HQ had no need of stout defences. Expendable, it would be abandoned long before the enemy reached this portion of scrubby plain thousands of miles from the battlefront. Therefore the anxieties which gnawed at the base’s personnel were strategic, not tactical; large concerns rather than hot anticipation of immediate attack.

However, today the officers of the General’s staff had begun to notice that their commander was moodier than usual. It was puzzling. It seemed unlikely that the military situation could alone be to blame.

Admittedly, the fall of Skyyon was disturbing: it made one queasy to think of the polar city conquered with hardly a blow being struck in its defence; the seat of the Sunnoad, the Noad of Noads, overrun –

Almost unbearable to watch was the film taken of those last hours, in which laden hover-barges dropped like tears from the city’s rim to the plain below, bearing away to safety the vital treasures and archives of civilization.

Yet the loss was retrievable, indeed it certainly would be retrieved if all went according to the long-term plan for victory; if, that is, the Sunnoad’s gamble worked…

A mighty big ‘if’. This thought went round and round in the heads of all those on duty at the base. All very well to repeat to oneself that the strategic withdrawal will coax the invasion from Fyaym into a trap of where it can be destroyed once and for all, and that this sharp medicine is better than the burden of a long war. A bold and considered strategy: yet there were moments when it felt like a walk upon rotten floorboards. And the stress must weigh most heavily upon those who saw the risks most clearly, namely the top commanders.

Especially, perhaps, omzyr Jovald Veon.

Tall and fit, with night-black hair and rugged features, he looked the part of General, but as the strain gnawed at him he was seen to tremble like a sapling. Up till today, he had managed with cool competence. His staff had gained strength and reassurance as they watched him second-guess the weaving, looping paths traced by enemy airships probing in widening circles through the spaces of Syoom… as they were still encouraged to name the land: “Syoom”, “civilization”, “the statistically comfortable area”, defined as that portion of the giant world Ooranye in which one lone voyager has a more than fifty percent likelihood of completing a thousand-mile journey alive. At times like these one remembered the definition most strongly, and the more one doubted it the more one continued, in defiance of disaster, to use the beloved term “Syoom”. The orders Jovald Veon gave to his captains were designed to maximise the chances of keeping Syoom real: in tightly coded messages he instructed them to offer just the right amount of resistance to the enemy ships, so as to convince their captains that the weak opposition they currently faced was the most which Syoom had to offer. Those orders had been masterly in their insight and precision – but then came the news of Skyyon’s fall, and something odd seemed to happen to Jovald Veon.

The tension lines around his mouth grew tighter. His voice cracked as he gave his orders. He accompanied his words by futile chopping gestures, or, as if to restrain himself from such action, he plunged both fists into his pockets. Often he would stare out between the silver columns of the HQ building, like an artist or poet who waits for inspiration. And then the tremors would come upon him.

The truth, unbeknownst to his officers and secretaries, was that inspiration had come.

It was bringing him to a decision which, unsuspected by himself, would cause controversy down the ages.

The most unsettling emotion is hope, thought Jovald. I never guessed that hope could be so threatening. Or that it could ever come close to making me forget my duty. But then, I never suspected, till this war started, that an enemy would hand me an excuse to say No to those of my own people who opposed me, and Yes to the happiness which they denied me.

The fall of Skyyon could be his excuse – his personal excuse – to take action of his own, against his private tragedy.

He was quite certain that he could take everybody by surprise. Neither friend nor foe, neither superior nor subordinate, would guess until too late at his opportunity to act alone.

The route to his success lay concealed within his third duty: not strategy, not tactics, but morale.

Unlike any other war, this one, as far as appearances were concerned, imposed the duty not of maintaining but of depressing morale: for the gigantic confidence trick which the whole of Syoom was playing upon the Quonian enemy required the peoples of Syoom to put up a pretence of despair.

This in turn required tremendous attention to detail, plus an almost fantastic degree of discipline. The plan demanded that the public mood seem dismal and defeatist, and since any normal everyday talk in the conquered cities and towns stood a good chance of being connected with the war, all humdrum conversation formed a vast reservoir of deceit, vulnerable to the constant risk that the entire trick might be exposed in one moment of carelessness. So far, Jovald had successfully maintained a sham radio dialogue with the occupied lands. He had sent gloomy messages exhorting people to bear their lot with stoic fortitude; he told them to be ready for sacrifice and to be brave whether or not final victory was ever achieved – and putting it this way, he made it sound as though he did not believe in victory. Each report he received, he turned into an excuse to send more advice tinged with the message that Syoomeans must lower their expectations. He made the point that the previous era, just ended, had been one long unequal struggle to postpone the inevitable, and that it wasn’t surprising, therefore, that the final fall of the Rubidium Fort had opened the floodgates of enemy pressure, resulting in the present invasion and perhaps the end of Syoom. “We must not complain if our light goes out, for it has shone fair in the history of the world. No culture is immortal. All great civilization have their term…” He churned out this lugubrious stuff and the population were playing along, intelligently taking their cue, and so far the enemy eavesdroppers had been completely fooled by the defeatist disguise, while in reality in millions of Syoomean hearts the fires of hope burned secretly bright.

Now, from fooling the enemy, Jovald Veon turned to fooling his own side.

Smoothing his face, he crooked a finger at his second-in-command, zynzyr Hyl Devadan.

“Yes, omzyr J-V?” said the zynzyr, stepping smartly forward. He had been watching the General as closely as he dared.

“Hyl, I need to explain something.”

“Yes, omzyr.”

“The fall of Skyyon,” said Jovald, “will put a lot of extra pressure on the deception plan. It is, after all, a real disaster for us.”

“I see that, omzyr.”

“So, on the one hand we need to make sure that our simulated despair does not become real; on the other hand we need also to make sure that the appearance of it deepens. As would happen, were it real.”

Hyl Devadan said, “Calls for finesse, sir.”

“Indeed, we have reached the point of maximum danger. A situation in which fear and uncertainty may make some of our people fight too hard too soon, and give the whole game away. – Now then, Hyl, you know, do you not, that the Sunnoad has given me this.” And the omzyr held up an orange glass object. It was shaped like a comb, with an inner purple shimmer. “You recognize it?”

“The signet of discretion,” husked the zynzyr.

Satisfied with the look of awe on the other’s face, Jovald carefully replaced the object in its pocket inside the folds of his cloak, and spoke in a lowered voice. “I showed it to you because I do not want to hear any counter-suggestions from you or anyone else.”

“Counter to what, omzyr J-V?”

“I,” emphasized Jovald, “have been given absolute discretion by Sonnoad Jad Darkal himself, and that is the proof.”

“Discretion to do what, omzyr J-V?”

Jovald forgave the questioner; the business was outside normal experience.

“To cook up something special for the Quonians.” The omzyr’s face was a touch shiny with sweat. “If the Sunnoad can trust me, so can you.”

“Of course, omzyr. Of course. But –”

“But?”

“Are you about to leave us, sir?”

“Yes; you are in charge of the base for the next few days.”

The zynzyr paled. The omzyr added gently, “I don’t expect the enemy to push much further towards this spot while I am gone; they are veering to sweep up the heartland. But if they do come at you, well, you know the steps of the dance we’ve been leading them.” His subordinate saluted and was about to step back, but held still as Jovald Veon mused, “Or call it a banquet, rather than a dance. I want to make personally sure, that the sauce is heated just right for this particular meal.”

Left to himself, Hyl Devadan drew himself up straighter to stand proud at his new post before the winking status boards.

2: Vlamanor

So far as it went, the excuse that Jovald had given to Hyl was true.

When is desertion not desertion?

Answer: when you’ve been given Discretion!

Secretly, elatedly knowing, at long last, that you have people just where you want them. Great… though accompanied by a croak, perhaps I’m behaving monstrously.

Jovald was a public figure whose personal tragedy was well known. To be famous on account of a one-in-a-billion fluke which had ruined his chance for happiness, was mortifying as well as miserable; not that he was too proud to accept sympathy – sympathy was welcome when it was offered on a friendly, individual scale – but he found it hard that he existed as a curiosity for connoisseurs of misfortune. The public paid to his peculiar ill luck was a thing he resented, well-meant though it was. Embittered, he found his professional success to be an inadequate recompense. Eventually he’d got into a habit of deriding his own abilities: what was the use of being acclaimed as a great general, as Sunnoad Jad Darkal’s right-hand man, if all his brains and strategic sense failed in the area he most needed help?

Until this morning, that is.

Now all of a sudden an old daydream had materialised.

Achieve a coup which will force the bigots to allow you the woman you love? Today at last, that’s possible! For the first time you stand a chance of turning their objections against them.

Jovald swept his doubts and hesitations under the carpet of will-power, and justified himself by due attention to the practical matters where his interests and those of Syoom must coincide.

The first step was to get clear of the base building without alarming its personnel. He went to the skimmer-park and mounted his vehicle casually as if merely setting out for an inspection tour within the security fence. By the time he reached the main gate in the fence, he had a different story ready: he wished to have a look at the ancient Lithium Era cannon – the one local relic of a town which had long since crumbled to nothing. The cannon stood poking its huge snout at the sky a short way beyond the base’s grounds. His genuine archaeological interest was already known to the people who worked with him. Tongues would not wag just yet.

He circled the cannon once and then, on its far side, set his skimmer in the direction of the city of Vlamanor.

The Quonian invasion was in its early days and although the enemy held Vlamanor their rule had not been consolidated. So said the reports: and Jovald could reasonably assume that they were right, to the extent that the Quonians had not yet established firm controls on the movement of population. They must still proceed by crisis management. From hour to hour they’d be relying on the reactive reach of their navy, on the fire-power of their ships and guns to quell disturbances, rather than on the preventative routine of meticulous patrols. They would not shoot at a lone traveller who wore farmers’ garments. These, he now took from the storage compartment. He congratulated himself on the unconscious foresight which had led him to pack the coarse clothing.

Of course, once I actually get into the city I shall no doubt find that by this time there will have been some ugly incidents involving the occupiers and the civilian population. You can’t have an invasion without nastiness. But at the moment the invaders are on their best behaviour, and such clashes will have been kept to a minimum. From my supervision of the airwaves I would have heard were this not so.

It was reasonable, therefore, to hope that he could avoid any unpleasantness until he had safely sent off his message to Ralath.

Thus reassuring himself that he was not an irresponsible idiot, the omzyr skimmed north-eastwards over the plain, while the base which he had abandoned and the ancient sky-fingering cannon dwindled behind him. Soon he was utterly alone between ground and sky. The crowded emptiness, the silent voices, the packed solitude of the dim Uranian wilderness pressed around him with their phantoms of possibility; but though he scanned the horizon innumerable times during the next three hours, only once did he spot the floating skeletal tetrahedron of a Quonian skyship. Its crew either did not see him, or did not think it worth altering course to intercept one solitary skimmer.

Presently the topmost towers and aerial decks of Vlamanor hove into view.

A somewhat bedimmed Vlamanor. The visible portion, extending downwards with his approach, showed fewer lights than in peacetime. Still, the city remained a beacon of glowing colour for the plains around, its upheld floor laced with the bright ribbons of traffic threading the geometric jumble held aloft by the concave stem of iedleis, the ultimate metal.

Wonderful structures, these city stems and the floors they supported: forged to last for thousands of millions of days, many times the current length of human history. To Jovald, momentarily struck with the comparative transience of human affairs, it seemed almost as if the present war and its outcome hardly mattered. One war: how serious was that? It could hardly dent the glorious tale of life on the giant planet Ooranye… so what then of the affairs of Jovald Veon? What about his courting of Ralath Noom? Did the fates of two individuals matter even less?

They matter, he said to himself, because uniqueness matters.

Two incarnations, just two lives to live, were all that most people had; and she and he were both in their second.

Even if we both turn out to be one of those rare cases who are granted a third life, the chances are vanishingly small that we will again be born contemporary with each other. It’s quite enough of a marvel that it happened this time. For it to happen next time as well, the laws of probability would need to be re-written.

Conclusion: there will never be another me and another Ralath Noom at the same time.

Therefore, if we don’t find happiness this time round, we’ll have lost it forever.

Happiness! Amazing that an omzyr, a general commanding over sixteen thousand men, should dwell on personal happiness in wartime!

But it was the war that gave me the idea…

Continuing his approach to the city, he reached into the skimmer’s bow compartment and took out a telescope which he trained on the docking platforms that were spread in a lofty halo round the topmost towers of Vlamanor. Up there one of the enemy Quonian tetrahedra could be seen drifting at its mooring. He wondered how many of the crew were still on board. Some look-outs ought to be there, watching the plains; the rest of the crew would have joined the city garrison.

Closer he skimmed, and entered the agricultural zone which crawled with moving lights as other travellers, farmers with their hover-drays as well as skimmjards like himself, plied the lanes between the fields of glowing vheic. Business as usual, in that respect anyway, and likewise the fountains of traffic riding the ayashou up from the plain showed that the normal method of entry to the city was still in operation.

Jovald eased himself into one of those currents. The nearest ayash took hold of him and he began to rise; a half minute later he had soared up and over the rim.

He settled onto the oalm or landing-plain. He had arrived.

Following the normal routine of a newly arrived traveller he slid his skimmer into one of the storage lockers, then, as was customary in Vlamanor, sought to exchange it for one of the smaller skimmers (‘floaters’), suitable for use within a city. But the rental office was empty. On its door was a placard saying that the service had been suspended until further notice. It was the first practical sign that the city was under enemy control – its floaters no doubt reserved for use by the garrison. Jovald shrugged at the minor inconvenience: he did not have far to walk down one of the radial avenues.

Only a few people were to be seen on the rim. Further in towards the hub, the crowds became denser and during his stroll along the avenue he first began to notice a handful of armed Quonians mingling with the native Vlamanorians. He saw no swagger, no shrinking aside, merely a mutual aloofness, a coldness of natural resentment: it was, so far, a clean occupation because it was a clean war. And it was a clean war because the enemy were getting everything they wanted so far. As soon as this ceased to be the case – as soon as the invasion met with serious reverses – they would resort to more unpleasant patterns of behaviour but, thought Jovald, this won’t happen before we are ready for them… Meanwhile he strode onwards and nobody looked as though they might stop him. He felt quite free to observe.

Most of the enemy floaters and strollers whom he passed on his way belonged to the more primitive species in the invading alliance: the Lotch and the Vraik. In battle they had shown themselves to be numerous and well-armed but not particularly well-brained. Leadership came from the Quonians, who had ample brain but, fortunately, were not so numerous.

Jovald reached a kiosk; his pulse thumped and joy upwelled in his stomach as wars and strategies receded from his mind. A message-booth at last, in the right district. I’ve done it, I’ve got here, no matter what happens next.

Shouldering his way into the booth he punched the number which he knew by heart. As he did so he prayed to the World Spirit that Ralath had not changed her job. His last news of her was a few days old… ordinarily not long, but during this tumultuous time –

The screen flashed on and showed the inside of a hotel lounge which had been turned into an office. There she was, sitting at a wide table with a group of other women. One of these rose to answer the call, blocking Jovald’s view of the rest as she approached the screen, and he could not immediately tell whether Ralath, who was still sitting, had seen who he was. Dismayed at the twanging of his nerves he rebuked himself: surely an omzyr could cope with a screen call. Faintheartedness at this point will have to be paid for with a lifetime of regrets.

The woman said, “Protectors of Orphans at War. Who are you?”

“Omzyr Jovald Veon, despite not looking the part. May I speak with Ralath Noom?”

The woman blinked in disbelief. “This is a meeting of the Protectors – I –”

“I know of your great work,” Jovald said agreeably, “and I shan’t take up much of Ralath’s time. Just tell her to come over to the screen, will you?” And he held up the Signet of Discretion.

He only held the thing casually, as if he were what it looked like, a comb which he was about to run through his hair, but the woman recognized it and gasped. A moment later she was off-screen.

Good, good, go on, fetch her, panted the mind and fizzed the blood of Jovald, and then, as the face of Ralath at last blazed its beauty at him, his heart thudded to a stop while his wits scattered, as happened every time, caught off guard by that same old churn in the guts which had made a fool of him so often in the past.

Heartbeat resumed as his mind reached for a defence which sometimes worked – the trick was to find fault with her appearance. Secretly, he reminded himself that Ralath was not perfect. Her teeth were uneven, for a start. Her chin a little red…

“Jovald, are you mad? Speaking your name and rank like this in public?” Her tone might have shrivelled his courage, except that her last word did recall him to his senses.

She was referring, of course, not only to the unique social prohibition which had long kept them apart, but also to the fact that one sure way to show up on enemy monitors was to use the public vidphone system in an occupied city.

“On the contrary,” he breathed, “I am sane. I must stay public – if I am to speak to you at all.”

“Explain!”

“Will you meet me for lunch at the Embers?”

Time slowed around this pivotal question. Then it wobbled at a faster rate as he saw her lips curl up at the corners. A wild notion came to him, that she had guessed his whole strategy.

She

said, “I am getting rather hungry. In

half an hour – is that all right?”

3: Street peril

Well, he had done it: he had made the call. That particular operation was a success.

He swung out of the vidphone booth and leaned against its side. Of course the authorities had listened in. Gazing at his busy surroundings he imagined the outward ripple of his “private” conversation through the city-scape and beyond. By broadcasting his tryst he had ensured – if his calculations were correct – that he could now make his way to the Embers in reasonable expectation that he would get there unmolested: they’d want him to get there…

Nevertheless as he began to walk his senses were primed like those of a hunted animal. The city was dimmer than usual, with much of the energy that had been used for illumination now diverted towards the enemy’s war effort; the business-corners and entertainment niches now had to function on reduced light. When he reached the inner ring called the Ezem, the circular avenue which revolves at the half-radius of Vlamanor, he found that the famous concourse still moved at its age-old speed, but shorn of its halo of brilliance. He stepped onto it and was borne past blacked-out mews that seemed enlarged by their obscurity.

Disappointment, when it came, was sadly complete.

One arm was seized above the elbow from his left side, the other from his right. Two grey figures had fooled him by their apparently random, separate approaches. Now they had him in a reporznt grip, the martial art that deceives by slowness.

Together they edged him into an alley. It was one of those spaces which gape like caves in the loosely heaped jumble of a Uranian city. Here in particular, though, in an area subdued and bedimmed by conquest, the effect was more than usually speluncal. If any citizen had seen him being whisked away, nen would not protest. Had not the Sunnoad himself instructed his people to bear all insults and bide their time?

From the stocky outline of a third man who stepped forward, Jovald deduced rather than saw the coarse features of a Vraik.

The man flicked a torch on and shone it in Jovald’s face.

“Hold him still, let’s take a look at him…” The gravelly voice spoke recognizable Nouuan though it crunched the syllables. “Omzyr, you were smart not to yell.”

This gloat was echoed by a fainter snicker to either side of him.

The captive listened, silenced by his own dismay. Not only must he admit to himself that his hopes had been destroyed. Not only were his arguments, his guesses, his predictions junked. He must also face the fact that he had been selfish to an appalling degree – amounting to treachery. To let himself get caught like this was to invite disaster for Syoom. If they squirted him with truth-drugs how could he not reveal the Sunnoad’s great plan? Only one way out was left to him. He must get killed resisting. He tensed for his act of final atonement –

And hesitated for a moment while he checked that this would not be yet another mistake. He must be killed. That meant, he must lose the fight. Yes – a good enough bet. Though he should be able to take these two oafs, the third one, waiting out of his reach, would then get him for sure.

Almost happy that he was about to burst the bubble of his failed life, Jovald Veon stepped back and pulled his clutching enemies towards each other so as to smash their crania in the last second before their hidden colleague gunned him down; but things went nauseously wrong.

He felt a ripping apart of that which he tugged. Then he was the one who was thrown off his feet. As he fell, his eyes – now dark-adapted to the alley – registered that the two “men” were not, after all, men. They were Lotch, their bodies peeling into fluttering rags, scraps of writhing leather in nightmare flexion –

Jovald rolled on the metal floor in an effort to evade the horrors and to draw his laser, but his every reaction lagged hopelessly behind the speed of events. The rags, before he knew it, had slapped together again into standing figures, and these rebuilt Lotch, cackling, held him down with their bony arms. Close-up, he saw on their faces and necks the jigsaw lines which betrayed their nature: the man-mimicking colony of protoplasmic crusts.

Meanwhile the third element, the Vraik, the human enemy, had stepped forward. He wagged his laser down at Jovald while he spoke to the Lotch, words - in his language or theirs - that ended on a rising note.

The patchwork creatures made no answer. Intent on their victim, their features seemed to squirm and then dissolve. Worse things then began to happen as Jovald, befuddled with loathing, saw them lean close. Their now-faceless heads were unfurling like petals.

The despairing omzyr tried to cry out to the Vraik, you at least are human, can’t you stop this, but what came out was a mere gasp. A remembered fact, that human brains were a delicacy to the Lotch, caused him to choke.

At that moment a cone of light flooded the scene and a hard voice rang out, freezing the Lotch. The voice lashed them again and they drew back, heads closing. Jovald lost no time in scrambling back onto his feet.

In unsteady relief he bowed to the fourth arrival.

Of all the Fyayman horde the chivalrous Quonians were the closest to Syoom’s Nenns in appearance and culture. If they were to conquer and rule us, we would merely lose our political liberty, not our way of life.

The Quonian officer was short, stocky and helmeted. From this headgear the light came, a nimbus which enveloped the man’s uniform in misty silver, signifying high rank among his status-conscious people. The two Lotch and the Vraik stood aside like children who fear rebuke.

The Quonian bowed back to Jovald, whose former optimism now slid back into favoured place as though he had never ceased to believe in his plans. Fate would – must – allow him to win. Thoughts of courting death were forgotten.

Out of the corner of his mouth the Quonian spoke in acid tones to the Vraik, who replied submissively. The Quonian then switched to the Nouuan tongue as he addressed Jovald:

“Omzyr J-V, I am Quarin Yadqual, of a rank equivalent to yours, in the fleet of His Luminosity Quelm the Fifty-Ninth, Quonant of Quonia. I welcome your entry into His Luminosity’s dominions. Allow me to state your position. Your arrival inside the territory of the New Empire has been taken to imply that you have resigned from the Syoomean Navy.”

Jovald said nothing.

“Lesser powers,” Quarin Yadqual continued, “in our situation would have defined you as a spy and treated you accordingly, but the Brilliant Folk scorn such reactions; we leave such attitudes of insecurity to the lesser breeds. So, you are free to come and go as you like, as a private citizen here in Vlamanor, henceforth under the protection of our laws.”

“I thank you, sponndar Q-Y.”

“It is no great matter. Obey the law and we will not interfere with your social life. I apologize for the crude behaviour of those who – due to the regrettable necessities of the moment – are allies of Quonia. And so I wish you good day.”

“I

sincerely wish you the same,” replied Jovald. The day seemed the brighter for the

haze of thankfulness in which he set off once more, knowing, and not caring, that

Yadqual was gazing after him with a satisfied expression.

4: The would-be Corrector

At sector HQ meanwhile, for some hours since Jovald’s departure, Hyl Devadan had felt buoyant, enjoying the sensation of being in successful charge – success meaning the absence of disaster.

Enemy radio was easily overheard, and those of his monitoring staff who sorted through the chatter could confirm that Jovald Veon had been sighted in Vlamanor, merely as a refugee, not as a spy or prisoner. Hyl thanked the skies (or the fate-waves, or the providence of destiny) for the enemy’s laxness.

However, a run of good luck must be paid for sooner or later. That was the fighter’s superstition, ingrained in the mentality. The only question was, when and how heavy the payment would be. Broadly speaking, the longer the wait, the worse the penalty. Hyl Devadan was therefore was almost glad when the communications officer uttered the words:

“A call on the red, zynzyr H-D.”

Words that dried the mouth. Hyl did not need to be told that “on the red” meant that the call must originate from the flagship Ayeis Dcifen. Knowing whom he would see, he strove to compose himelf as he turned to the monitor screen.

As expected, it at first displayed part of the humming control-room of a skyship which currently hovered in the vicinity of Toolv, away on the other side of Syoom; then that view was occluded by the head and gold-cloaked shoulders of a swarthy, young-to-middle-aged man with burning eyes and a hard jaw.

Jad Darkal 35480 was a warrior Sunnoad the like of whom had never before been known. He was acknowledged to be a good person in every normal sense of the word, yet his main interest in life appeared to be battle: fighting, preparing for, or studying battle; as though he had been born for no other purpose than to lead Syoom against Fyaym in this desperate time.

Perhaps such men existed in all periods, and only now was one called forth; in which case the selection process for Sunnoads must be godlike in its prophetic wisdom.

Jad Darkal said: “I want Jovald Veon’s report.”

“Sunnoad J-D, the omzyr is not here. He has left on an undercover mission. At least…” Hyl hesitated.

The Sunnoad gave a grim nod. “You are thinking that it may not be undercover any more.”

“You heard…?” probed Hyl.

“Not heard. Guessed. From reports of reports, which lose coherence as they are relayed. Enough to convince me that Jovald is up to something on his own, in enemy-held territory.”

“I have heard he’s been seen in Vlamanor, but, Sunnoad J-D, I have no more details as yet.”

“Knowing that character, nothing will surprise me. If you learn more, inform me before you take any action.” The Sunnoad broke the connection.

Hyl Devadan was thus left to wrestle silently and alone with fantastic thoughts of the omzyr’s possible treachery…

…Meanwhile the debate continued on board the Ayeis Dcifen.

The Sunnoad, turning from the monitor screen which had shown Hyl’s face a moment before, met the gaze of the wizened savant who was his counsellor and would-be Corrector, Marad Sydel.

“So then, Marad, will you seize this opportunity to say, ‘I told you so’?”

Sydel gave a shrug. “At times you were wont to say, Sonnoad J-D, that to order the replacement of the omzyr might prove as dangerous as to keep him. Your reasoning was, you did not wish him to take alarm and flee with all he knows… yet now he appears to have done exactly that. So, yes, I told you so.”

Jad Darkal said: “Then prepare to be worried.” It was one of his phrases. Ever since his elevation to the sunnoadex he had experienced the almost indescribable sensation of (as it were) inhabiting himself. It felt like looking out from the top storey of a living mansion built from the lives of his 35,479 predecessors who had worn the golden cloak. “Jovald Veon,” he continued, “is a problematic tool. From the moment that I gave him Discretion, I realized that he might misuse it. I am gambling, nevertheless, that his grievance will work for our side, so that his gifts won’t go to waste.”

“But what will you do, Sunnoad J-D?”

“Right now, go to my cabin and lean into the latest stack of reports – and you’re going to comb through them with me, sigh though you may, Marad; you must know I won’t have you say that I covered up for the troublesome omzyr.”

Marad Sydel bowed his head. In addition to playing the part of a sounding-board, he had the secret ambition to be a Corrector: that is, one who gets away with coercing a Sunnoad. This most dangerous of all political games requires a special set of circumstances for success; the death penalty is the accepted lot of a would-be Corrector who fails to prove his case to his master – fails, that is, to convince him after the event that the coercion was justified. Correctors thus appear rarely in history. But this business with Jovald Veon had some promising aspects…

For just think – Sydel declaimed to himself in his imagined stance, as he addressed the imagined court of inquiry: if that omzyr in Vlamanor has gone to the bad, I shall be vindicated.

Later, more promising still, in the upholstered cabin the counsellor became spellbound at what he saw across the littered table: a really worried, brooding Sunnoad. It was a rare sight to watch and hear the man in the golden cloak soliloquize as he shuffled papers, as if he were delegating procedures to his hands while his mind tried to deal solely with destiny’s terrible requirement to be right:

“What choice did I have?” murmured those lips, or so it seemed to Marad; he could pressure himself to believe that he knew exactly what the Sunnoad was thinking because he knew what the man ought to be thinking and therefore must be thinking in order to fulfil the life-promise of Marad Sydel. “We cannot go into Fyaym to look for our enemy; Fyaym is too big, it’s four fifths of the world. We’d dissipate our forces and come to ruin. No use.” Jad Darkal was shaking his head at his own words. “The only other option is what I made us do.” The voice became hushed; if only it were louder, instead of an almost whispered mumble! – but still it was guessable by Marad as it went on, “What I made us do… invite the Fyaymans into Syoom by a pretence of weakness,” and now his eyes blazed all of a sudden – ah, thought Marad excitedly, this proves it all – nevertheless a glare made him flinch – “ConVERT,” the Sunnoad clearly pronounced, “the fall of the Rubidium Fort. Convert it from disaster into opportunity.” The eyes faded back to dullness. As so they should. They must be resigned to the guilty truth. Here came the confession. “The responsibility is mine: I planted the stories which enticed the enemy to take his swift advantage; the invasion, in that sense, is my doing.” Back and forth continued their mumbly see-saw. “And since I myself am guilty of so much, how can I not be lenient with the lesser tricks of Jovald Veon?” The lips ceased to move. With a sigh the Sunnoad looked up.

Then he really spoke.

“Daydreaming, Marad? Go finish that stack.”

5: Deal at the Embers

As he strode up the crescent steps, Jovald knew what his advantages would be, and how he intended to exploit them the moment he got beyond the hotel’s arched entrance.

Though he could hear his heart thud in his chest, he was beyond hesitation. An expert sportsman need feel no confusion when about to perform a difficult but well-rehearsed feat, and Jovald had likewise disciplined himself to make it easy to saunter through a lobby and past reception and through glassy inner doors, into the rounded space, the size of a concert hall, where he must act like he owned the place.

Tables for two, for four and for eight were scattered around the Centrepiece where glowed the embers which gave the establishment its name.

Jovald could not immediately spot Ralath. She must be sitting somewhere on the Centrepiece’s other side. He began to circle round, pretending all the while to relax in the cosy warmth of the embers’ glow. The embers are formed from a rare substance known as coal. It is rooted in deep time, in a previous Great Cycle of Uranian history, when the stuff was widely used for fuel. Supplies of it were depleted almost to nothing by the dominant species of that day. The substance itself was formed long before that; hundreds of thousands of millions of days before, in a primeval, forested epoch which long pre-dates intelligent life of any kind on Ooranye. Good to know these things. Especially as the hotel management prides itself on using real coal for its centrepiece. Importing it, I guess, from remnants of Fyayman deposits, but wherever the source may be, the coal authentically glows, the fiery orange-red not faked.

“Nice shine, Thrello,” he said to a man cloaked in black and white who advanced upon him.

“Omzyr J-V, welcome back,” said the head waiter, instantly recognizing him through his farmer’s disguise. “Are you –”

“I’ll find my way,” smiled Jovald, and Thrello faded smoothly from his path. That had been an easy enough encounter…

Then around the Centrepiece she came in sight, waiting at a table for two.

Ralath Noom was on the cusp of middle age, with a good figure, superb deportment and brilliant auburn hair, but her features often, as now, looked somewhat stiff, making Jovald yearn to enliven them. Similarly with all her imperfections and drawbacks; they merely (confound them) intensified his adoration. He had become used to this. Nevertheless, her nod as he approached, and her quizzical smile, left him annoyed: after some hundred and fifty days of separation he might reasonably have expected something a bit more intimate than a pert expression which seemed to say no more than, “Hello, what in the world are you up to this time?”

On the other hand, after all, he was hiding his feelings; surely she could be permitted to hide hers. And skies above, he was a commander, wasn’t he? A respecter of discipline, including self-discipline, so then, be fair, and respect hers!

He sat opposite her, his elbows on the table.

This is more like it, he thought next moment as she leaned forward and clasped his hands. Her face leaned close to his. (Skies above, you can never tell with this woman.)

“Jovald,” she said caressingly tone, “don’t look to your left.”

“Uh?”

“The table near the window. Don’t look. They’re from the Clean Lines Society.”

More mystery, but the biggest one is the mystery of why I bother with her. I really thought she was going to say something warm just now, whereas in fact she’s just playing games for onlookers’ benefit.

Ralath murmured on, “Perhaps you know what to do with them. For me, the main thing is, you’re here. It’s been so long, Jovald.”

She does care! I should never have doubted her!

Please stop see-sawing, O my mind.

He squeezed her hands and assured her, “I know exactly what to do with the Clean Lines people.”

“Are you serious, Jovald? Can I trust you on this?”

“You can – at long last.”

In an even lower voice she added, “You really have found a way for us…?”

“Thanks to the war,” he nodded.

“I don’t understand. I don’t understand.”

“Of course not,” he smiled at her. “But you will soon. Our friends over there are getting up, I see.” He broke off as three men and two women flowed forward, to occupy the closest tables and to turn their chairs to face him and Ralath.

At the same time he noted the dark green uniform of a Quonian sponndar seated at a more distant table. This might turn out useful. Probably, thought Jovald, the Quonian has a voice pickup trained on the gathering around me; I hope so. It will make my task all the easier.

In the military and political sense, the Quonian was an enemy, yet as far as Jovald was concerned the enemy – in a far more important personal sense – was the group of fellow-Syoomeans close by.

One of the women, smartly cloaked and elderly, addressed him in a voice ripe with disdain: “Omzyr J-V?”

“I am he.”

“And the lady Ralath Noom, of Hoog?”

Ralath nodded stiffly.

The speaker went on, “My name is Omwa Sisk, and I and my colleagues are –”

“I know who you people are,” growled Jovald. “Every city I enter, I meet C.L.S. snoops.” He fancied he could almost hear a “click” as the woman’s haughtiness intensified.

“If that is so,” she snapped, “no further introductions are necessary and I shall state our business –”

“That, too, I should know by this time.” Jovald felt grim glee as Omwa Sisk bridled further. “But,” he conceded, “I can listen once again.” Indeed I am willing just once more. Little do they know that this is the last time. And yet, already, I perceive an ebb in their confidence. Their blather must henceforth dwindle into reflex, an arrogant twitch unsupported by reality. A fate richly deserved and absolutely appropriate for such small-minded folk amid the disasters of today’s world-crisis.

The moment drew closer when all comfort would be torn from the Clean Lines people and they would be left to shiver in the icy blast of humiliation, failure and defeat. And the delicious thing was, they couldn’t avoid it because they couldn’t adapt. They could only go on repeating their one message. It was all they had to say. Even if they were to find out that he had something new up his sleeve, their entire stance would continue to rest upon an argument which they had always considered to be rock-solid. Unfortunately for them, I have mined that rock.

Omwa was saying, “I don’t know exactly how well the position has been made clear to you by our colleagues in other branches, but I shall enumerate the main points which cannot be gainsaid, concerning you two, Jovald and Ralath.”

Ralath shifted uneasily, but Jovald shot a warning glance at her.

“Point number one,” continued Omwa. “You are both in your second incarnation. You have never denied this, and it would be useless to being to deny it now, for both of you have confessed to blurred and distant memories in the characteristic second-lifer style.”

“We don’t deny it,” said Jovald comfortably. “We are, as you imply, run-of-the-mill second-lifers. Like maybe five per cent of the world’s population, this far into the Great Cycle.”

Omwa, after waiting impassively for his words to cease, continued as if he had not spoken. “Point number two. There has been no skulduggery about your names. In both your cases, they were authenticated the usual way – namely, they were recorded as being the first sounds you uttered. Neither your parents nor anyone else made any attempt at concealment of these, your true names, Jovald Veon and Ralath Noom.”

“Agreed! We are who we say we are.” This is going like a dream.

“Point number three. There is therefore no reason to avoid the presumption that the Jovald Veon and the Ralath Noom in this era are the very same people as the Jovald Veon and the Ralath Noom who lived over a hundred and twenty million days ago, and married each other, in the Nitrogen Era.”

“Except,” said Jovald – I had better make some objection, though I must not overdo it – “the vast improbability of two people who knew each other in their first incarnation, actually returning so close in space and time that they also become acquainted in their second life.”

“Statistical improbability,” said Omwa, “is bound to happen, given sufficient opportunity. It would be more surprising if a few cases like yours did not crop up, in all the millions of combinations of lives in our world’s history. Reasonable?”

“Reasonable,” admitted Jovald. He must not to put her off as she approached her punch-line…

“Point number four. In that first incarnation you, Jovald, and you, Ralath, became the parents of…” She drew a sharp breath, then vomited forth the name: “Liucgr Ell.”

She then sat back and glared. Her face had gone red. Jovald wondered if his had reddened too.

The obscenity of the hated name was enough to sicken and embarrass anyone. Liucgr Ell. Activator of the Corruption Ray. Liucgr Ell. The arch-villain of Era Seven. Liucgr Ell. The monster who had maimed whole cultures – Careful, thought Jovald: I must be careful, now that I have reached this point. How can anyone maintain that there are two sides to this question?

Yet nobody knows what governs the return of souls. However, in case there is any heredity to them at all – in case there is the slightest chance that Liucgr Ell may return if his former parents wed again – action will be taken. If Ralath and I have a child, observers either from the CLS or the government or both will insist upon being present at the birth, and if the infant’s first sounds suggest the name of horror, it will – officially or unofficially – be killed.

Jovald’s romance with Ralath had up till now been ruined by this threat. In vain he had argued that the CLS’ concern was based on silly fears; that one coincidence did not make another; that there was no reason to suppose that Liucgr Ell would reincarnate via the same parents as before.

People wanted more than arguments. They wanted nothing less than to be sure that the fiend did not return.

Jovald dared not ignore their determination. Suppose he did marry Ralath and they had a baby boy who at birth happened to gurgle something like “Loogr-Ell”? The risk was too great. And even if that did not happen, still the child would face a life of suspicion, in which people would continue to wonder whether his was a mere given name, concealing a terrifying true name. Jovald by this time was thoroughly familiar with all the arguments. Though he had not agreed to them, he had bowed to them because he could not subject Ralath to such tension and fear. He had given in to the busybodies, had allowed them to drive him away from her again and again –

Until now. Now he did something different.

Savouring the moment, he opened his right palm. On it the orange Signet of Discretion sparkled.

Into the stillness he sowed a terrible idea:

“Syoom greatly suffered from Liucgr Ell, but what’s the point of worrying about that now? For we are a conquered land, which appears to have no future any more. I therefore see no point in resisting the birth of Liucgr Ell.”

“But the Sunnoad –” croaked Omwa.

“If the Sunnoad were here he would say the same. Otherwise he would not have given me this.”

Next, sit back, let them stare more at the Signet. Watch as awareness blossoms in them.

He knew his opponents were not so stupid as to need any further prompts from himself. Members of the Clean Lines Society had learned, just like anybody else in this war, to take part in the patriotic deception plan, whereby Syoomeans must feign despair in order to fool the enemy. And what more logical way to show that they had given up, than to withdraw their objection to his wooing of Ralath Noom?

So they had no choice but to take the hint he had given them. The Signet of Discretion glinted at them from his palm as he hefted it idly. Even without the sight of it, they got the point all right; in fact Omwa had got it even before she had finished her own four points, which was no doubt why she had spoken with increasing acerbity. She must have struggled with her own private despair. Jovald could feel a contemptuous pity for her. She and the others were sincere enough, and genuinely feared the rebirth of Liucgr Ell. As to whether he, Jovald, could forgive the Society for the hundreds of lonely wasted days it had forced him to endure, that was another question.

“I see,” rasped Omwa, her face sour with defeat. “The war has certainly changed things, so much so that, in these conditions of defeat, we should not take up one further moment of your time.” Pushing their chairs back, she and her colleagues stood up, looking as though they were about to spit on the table, but they had to swallow their spit instead.

For a few moments Jovald drank in his triumph as he watched them go. Then, shyness and diffidence invaded him anew, as he turned to look at Ralath.

She returned his gaze levelly. “That was clever, Jovald.”

“Provided it wasn’t all for nothing. Provided…”

He did not quite know how to go on. Provided I still have a chance with you, was the blunt thing he needed to say.

“Yes,” she broke in, misunderstanding him or pretending to – you could never tell with Ralath. “Your victory may be temporary, depending as it does on ‘these conditions of defeat’, as the woman said.” But something in the curl of her smile gave him a surge of hope and courage.

“I am not going to ask you if you love me,” he muttered. “I’m prepared to run the risk,” and he lowered his voice further to a whisper, “that you will marry me merely as part of the deception to save Syoom.”

“Risk?” she inquired, eyes dancing. Her hand slid across the table to his. “It’s always a risk.” Soothed by a vast joy, he began to be convinced that the hollow days were over.

6: The Wedding Deception

Jovald’s courting of Ralath continued to be a public affair right up to the date fixed for the wedding – Day 42 of the young Strontium Era; fourteen days after the meeting at the Embers.

The publicity was a guarantee of protection for them. It also, however, made such protection doubly necessary. Plenty of ordinary folk in Vlamanor, though not members of the Clean Lines Society, were nevertheless influenced by CLS attitudes and therefore worried about who a child of this marriage might turn out to be. Superstitiously, some feared that even if it were not Liucgr Ell himself, it might be someone just as bad. Debates became fierce. Some people sprang to the couple’s defence, arguing that even if Liucgr himself were reborn he need not follow the same evil path in his second life. For though the soul be the same, the character might have changed… the natural laws being in many respects uncertain.

Over and above all this was the paramount and silent influence of the Sunnoad’s plan. The open secret, the hidden hope and the feigned despair, meant that when it came to the point of action, nobody dared forcibly oppose the wedding of Jovald Veon and Ralath Noom.

To make doubly sure, Jovald let it be known to the Clean Lines Society that he and Ralath had both left documents, to be opened in the event of their deaths, which “told all”. The hint, he trusted, would be enough. Deriving enormous satisfaction from thus forcing the CLS to work in his favour, he next proceeded to take his fiancée to public places of entertainment, flaunting their romance in the face of society, relishing the fact that there was nothing society could do about it since it was now doing the Sunnoad’s bidding by giving the enemy supposed proof of the hopelessness of Syoom… and sure enough the occupying forces looked kindly on, while Jovald broadcast invitations to the wedding.

It was to be a lavish affair. Jovald hired the Yarpan, the great hall high near the airship docks, with its superb view over the city and its surrounding fields. Finally the big day came, and in his best cloak he stood in the foyer, welcoming his guests, while some yards away Ralath stood welcoming hers. Some truly were welcome: friends and well-wishers from near and far, private travel still being possible despite the war. Many others (he could tell) were present merely in order to take part in what to them was a charade, the purpose of which was the open secret’s strategic aim that the enemy might believe that Syoomeans no longer cared about their future. Besides, the food and drink were excellent… Jovald cynically greeted them all.

Somewhere inside him lurked a compartment of disbelief, like a secret cabinet drawer. Its compressed fear: all this might turn out too good to be true. Did Ralath love him or was that, too, a part of the charade?

The trouble is, what with so much grand strategy, my personal judgement is a bit off. Unavoidable… but then couldn’t she have made it a bit clearer what her feelings were? Instead of giving him so many of those little stilted smiles! Those shy, clipped sentences! There she was now, rationing her greetings to the members of a queue who were shuffling past her. Suddenly it came to Jovald that there was another explanation to her manner: it was not that she was discontented, nor resentful of him. Instead, the reality was: she was terrified.

I also, under the crust of my accomplishment, feel the quake. As if on cue, a hum became audible. The sound became intensified. It beat down from the domed ceiling. The guests murmured and tilted their heads to gaze up at the quivering chandelier.

Jovald sought assurance from Ralath: their eyes met. He nodded, and stepped aside to murmur an instruction to the master of ceremonies, who immediately struck a gong. Nothing could compete with that clang, to catch and hold the guests’ attention. Following the bride and groom, they filed into the central hall.

Meanwhile the humming slowly faded: what they had just heard, before the gong, was the departure of the garrison airship. The most likely reason for that was, the Sunnoad’s long-planned counter-attack had begun.

If all went well, within hours it would become conclusively apparent to the enemy that they had been fooled, tricked, trapped. Great news for Syoom –

But what about the marriage, no longer necessary for strategic reasons, no longer justifiable at all in the eyes of many?

Repeatedly he sought comfort and reassurance from Ralath’s face. Forgive me for bringing you into this, he tried to say wordlessly. She raised her brows and somehow, thank goodness, contrived merriment to sparkle from her eyes, showing that she had got the message and that the marriage ceremony, as far as she was concerned, could and should go ahead. Jovald turned his mind to what was therefore appropriate, the immemorial custom which has made the act of standing in front of a full-length multi-planed mirror the common part of all marriage services on Ooranye. He took his bride’s hand and ascended the platform which had been cleared for them.

While they stood there and kissed, their reflections and re-reflections symbolized the rebounding, criss-crossing supports of marriage and society.

They descended from the little platform, whereupon a cheer, loud enough to betoken sincerity, went up from the crowd of guests, in a specially good mood because the military significance of the garrison ship’s departure had made them sanguine about the prospects for Syoom.

On the other hand when they got round to thinking a bit more about it, they would most likely drift back to the Clean Lines stance. Then they might insist that Ralath and Jovald ought to be kept apart…

A heavy man in a rich cloak strode towards the newlyweds. Jovald eyed him warily.

“I congratulate you both,” Verzay Relk, City Co-ordinator, said coldly. “Your persistence, your… ingenuity has rewarded you.”

“Like many men,” agreed Jovald, “I had to win my bride against odds.”

“Yes, you’ve been ruthless, all right. Nothing stands in your way, evidently.”

“But for hundreds of days,” - Jovald matched the other’s dry tone – “I did allow you and your kind to stand in my way, to the detriment of my life.”

“Your life – your life.” Verzay’s words came with a sneer and he turned away, bowing ironically, barely preserving appearances.

Jovald, with a glance towards his wife, ascertained that she and he happened fortunately to be standing a few paces apart from all the others. “Ralath,” he risked the murmur, “I do fervently hope that you don’t regret what we’ve done…”

Stop, she gestured with a hand on his arm. “You fear,” she murmured back, “we’ve stored up too much hatred.”

“No, not that; time will heal it if we’re given enough – but that’s the question: how are we going to live meanwhile? And the only answer –”

She forestalled him. Wonderful creature that she was, she said what needed saying. “We must get out. Out of Syoom.” He scrutinized her expression and saw no irony, no bitterness: she really did understand.

Now he had the final reassurance he needed. Even if she was just making the best of a bad situation, the sufficient truth at this moment was that they had to get away. If they did – if they gained a breathing-space – he would then have the opportunity to convince her that she had made a worthwhile choice of husband.

“We have a few hours,” he said, “before battle explodes in earnest –”

She nodded, “That’s my guess, too.”

“So will you allow me to take you into Fyaym?” The sound of that last word unfurled in his mind like a banner of purple darkness; what a dismal moment for a bridegroom! Though his intellect trusted hers, as a lover he cringed in advance at the scornful reply which any bride might be expected to make at the mad suggestion of being taken into Fyaym.

She linked her arm to his, dispelling the nightmare: “Off we go, then. Honeymoon in Fyaym.” She said it lightly! At every point in the conversation so far, he had been dreading that it would go sadly wrong, and only now could he admit that he needn’t have worried. He had in every sense met his match. I’ve been slow, he realized, slow to appreciate the full wonder of my prize.

Meanwhile he – like all Uranians for whom the understanding was bred in the bone – knew he lived on an ideal world for those who wish to disappear.

7: To Get Lost

Context-awareness or apparng is the sense that furnishes the natives of Ooranye with a powerful sense of their world’s size and of the value of that size, especially for fugitives. Apparng tell everybody that humanity is spread thin, thin... so much so that, given the scarcity of patrols over areas so vast, you can always hope to slip away from a hostile regime, provided you have access to a skimmer.

A so-called one-man skimmer can carry two if need be. The pilot can sit inside, like a canoeist, while the passenger sits behind and astride, boots on the side-rests, hands gripping the supplementary control lever.

Thus laden, the skimmer carrying Jovald and Ralath took three days to reach sky-50, the invisible safety-contour which marks the frontier between Syoom and Fyaym. They crossed it at a point about 6250 miles from Vlamanor and well into the largely Fyayman region of Nyyn.

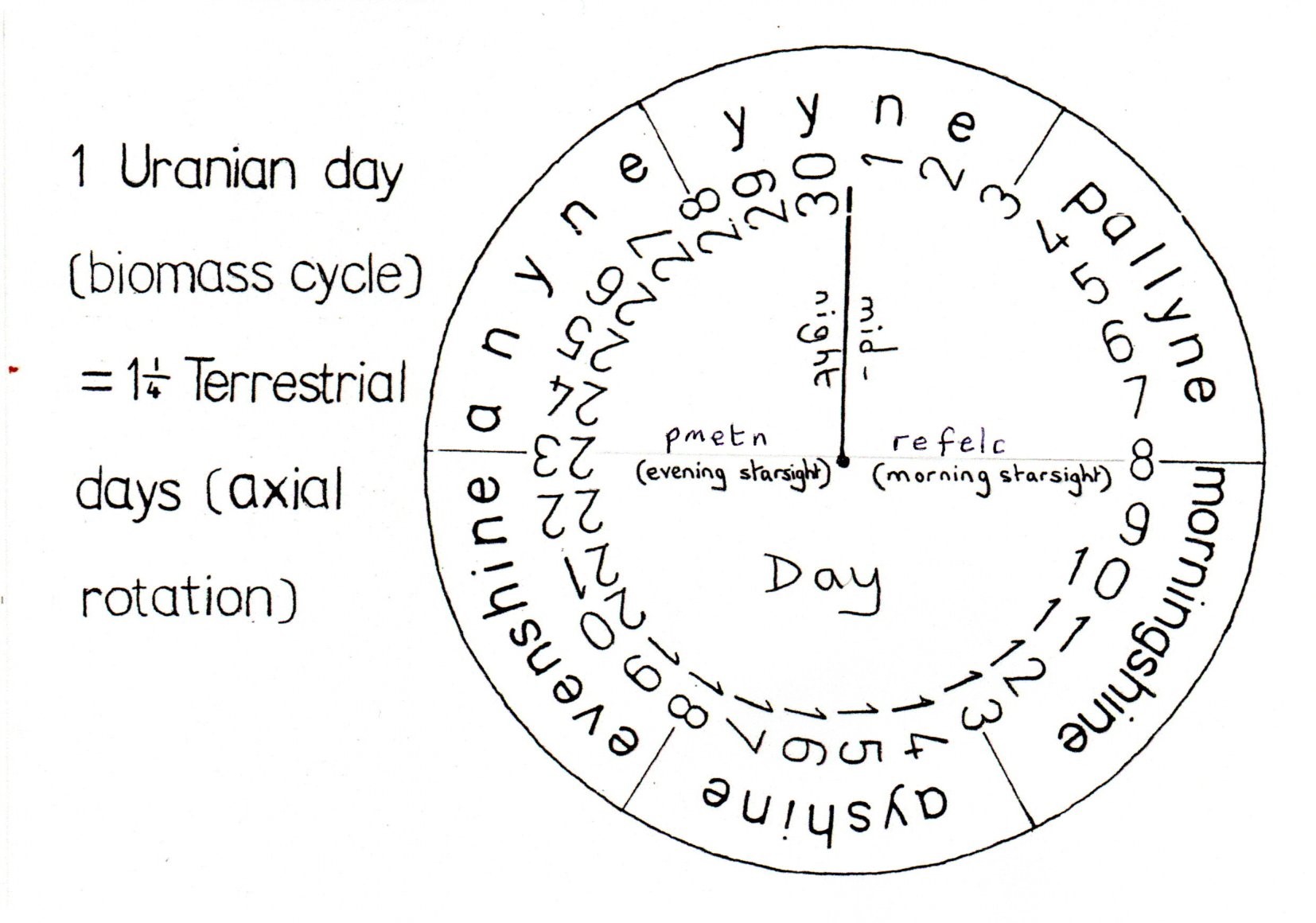

By that time they also knew that they were living in a new era. They had spent their wedding night wrapped in blankets next to their skimmer parked on the cold and endless plain. Discovering the warm, tender aliveness of each other was epochal in a personal sense, but when they also noticed a delay in the luminescence of the air next morning, the exterior truth dawned, that the turning point in their own lives had coincided with a global diurnal shift, an eomasp. Though the atmosphere brightened as usual from pallyne to morningshine, it did so in two fluctuating stages, the second pulse about four hours late; and a resonance with the mental excitement of millions of humans was the only force that could have caused such bad time to be kept by the natural biological clockwork of Ooranye. It must be, therefore, that a world-wide wave of emotion had sufficiently perturbed the mindless floating microscopic throom to put it off its stroke, messing up its usual thirty-hour rhythm of brightening and darkening.

And what could have caused that burst of mental energy? It must be the Sunnoad’s counter-attack. The product of so much secret planning, the bursting reward of all that self-restraint, this and only this could have caused the flutter in Nature’s heartbeat. All over Ooranye, therefore, people knew that the young Strontium Era had been cut short and that its Day 42 was being succeeded by Day 1 of the Yttrium Era.

“Really not such a coincidence after all,” remarked Jovald, his smile full of pride and cheer.

“You mean, the world owed us, personally, a new era?”

“I just mean, that if we were ever going to get away, we had to have cover on this scale.”

“Well, isn’t that lucky,” Ralath replied tartly.

Jovald said: “Well, yes it is.” He understood why her mouth had gone lopsided: to view the epic transition from one era to the next as a background prop for their own needs did seem a trifle egotistic on his part. “Anyhow, here we are, safe and sound,” he shrugged.

“‘Safe and sound’, he says! I like you, Jovald. You’re pleasant company, which is just as well, considering where you’ve brought me.”

“Thanks! – but you know, Fyaym, when one is in it, objectively can seem much like Syoom, after all.”

He spoke lightly but truly: an empty plain where the gralm extended as far as the eye could see, except where it was wrinkled by small ranges of hills, and dotted by groves of spiky katora bush or the blades of narps, could seem nothing special. Objectively, this was so.

Nevertheless from the start the additional colouring of expectation did tint the view. Gave it a difference… Everyone grew up from childhood with the knowledge of how Fyaym in literal terms is statistically defined, as the land in which a lone skimmer-pilot has a less-than-fifty per cent chance of surviving a thousand-mile journey. Everyone brought nen’s own imagination to bear on this idea and so draped it with some colour from nen’s own personal store of hopes and fears.

Anything might engulf an explorer in such a wilderness, where no city patrol would ever reach. New weed-kingdoms might grow between one random voyage and the next. Isolated species were likely to develop unseen. Overlooked cultures, oversights grown large, innumerable fates awaited the intruder.

How to better the odds of survival?

Well, the statistics agreed that two people were more likely to survive than one. Also: “less than fifty per cent” need not mean much less. The “continental shelf” of Syoom, where it existed, meant that, for some distance into Fyaym, hardened wayfarers could risk a long journey.

“Besides,” remarked Ralath, in a swerve towards agreement, “maybe we have journeyed all we need. We’re nicely lost without travelling deeper; from the authorities’ viewpoint we must surely have disappeared already, especially since Syoom and her enemies are tearing at each other and won’t have time to spare to look for two runaways who’ve annoyed the Clean Lines Society.” She folded her arms.

Jovald said, “And when the battle is over?”

Ralath said nothing.

“I get the feeling,” Jovald mused, “that the Yttrium, like the Strontium, may turn out to be a short era. Perhaps we’re still too close to the border, despite what you think. We’d better press on.”

Ralath did not ask what he meant; she simply wanted to know how they would live in deep Fyaym. “I’m not starting to get difficult; I just want to know.”

“You do know,” Jovald replied, “else you would not have trusted me this far.” He said it with his arms clasped tight around her, yet she jarred him loose as she spoke with bite in her tone:

“You are going to give me an answer, aren’t you? Or is this going to be our first quarrel?”

“We can live in deep Fyaym,” he replied, “if we find a fortunate oasis, an uncomplicated rest.”

“You mean that literally?”

“Why not? Could take the form of a fertile swale, a crystal grove, even a town in a sheltered spot; such mini-Syooms have been recorded now and then. We should have time, exploring, to find what we need. And given the luck, you and I between us have the skills to survive, do we not? How about it? Are you with me or would you rather return to face Omwa Sisk and the CLS?”

“When you put it that way…” she replied sweetly, and they laughed together.

Luck was with them. Deeper into Fyaym they skimmed, day after day, yet they lived on without any close brush with what might have expunged them from this record. And finally Jovald was able to point ahead to his “swale”.

It lay past a gentle hill, from beyond which came an unseen, self-explanatory mind-touch: a beacon of thought which allowed no doubt. Just a constantly repeated meaningless name: svalg, svalg, svalg… Jovald and Ralath halted their skimmers.

“Shall we…?” began Jovald. He saw the assent on her face. Instinct proclaimed to both of them, “it’s worth the risk”. The continuous beat in their brains – svalg, svalg, – pushed at them convincingly.

To push them away? Some feeble attempt to repulse them?

Topping the rise they came in sight of the swale, the shallow, wide, bowl-shaped hollow about a mile across. Filling it was a leafy, towny plant: a single organism whose broad green blades were interspersed with human dwellings. Dots – figures – moved among the leaves. Jovald and Ralath eyed the scene, guessing at the kind of deal that must have been struck.

The svalg was probably the one and only individual of its species; Fyaym harboured many such productions, each parentlless and unique. Doubtless immortal, un-reproducible, from time to time it invited another species into partnership.

“They’ve noticed us,” murmured Ralath.

One of the human dots down below had ceased to move, and another swerved to it as at a summons. Others gathered; a group formed; it began to move.

“Yes,” agreed Jovald, “and here they come.”

Simultaneously with a yielding “pop” inside their heads they felt the thought-beat of the svalg turn from pushing to pulling. From discouragement to welcome.

Epilogue

Many thousands of miles away, and a lifetime later, the crack reporter Jegand, on the prowl for a story, followed his hunting instinct to the Tnedon Estate near the city of Nuvium on Day 22,716 of the Zirconium Era.

A quietly ruthless young man, Jegand scanned with cold, patient eyes every detail of the beautiful sward and fine buildings amid the Tnedon grounds. The cork-textured gralm was springy underfoot, except where luxuriant grass bordered the central block. Around this, bright red flame-bushes were interspersed among the greenhouses where grew the famous Graol healing-herbs.

Their discoverer, Lek Graol, lay dying somewhere in the estate. Jegand was determined to speak with him before it was too late.

“Yes, it seems he actually does want to see you,” said the house-chief when the reporter applied at the reception window. “So I have to let you in. But if you ask the wrong kind of question you may hasten his death.”

“I’m not here to torment the fellow,” protested Jegand. “He asked to see me!”

“I’m not disputing that.” The house-chief looked glum, and continued, “But he didn’t say you could go in without being warned, so listen while I warn you: he really is what he’s reputed to be, namely self-critical, perfectionist, jittery about his past – ”

“Oh, come on, he’s not that weak. His life has been a triumph. He has always known what he was doing. And he has heard of me, he knows my field.”

Jegand expected to be let in there and then. To say that Lek Graol’s life was a triumph: that should have clinched the matter. A bit of flattery, but also true. It should have gone down well enough… but the house-chief still seemed inclined to hesitate. Something about Jegand evidently worried him.

“Also,” the man added, “I can choose when to let you in. It might not be today.”

It might not be ever, realized Jegand. He abruptly risked a startlement – the shock of absolute honesty:

“Look, even if he does die a bit sooner from telling what he wants to tell, have you the right to deny him?”

That worked. Without another word the house-chief, beckoning the reporter to follow, led him to a room where a shrivelled man of over twenty-two thousand days was lying on a large bed, his face immobile, his hands clenching and unclenching.

Jegand could sniff the closeness of the story he sought. The world was a haunted graveyard of unquiet mysteries; any journalist could make a living from the reappearance of issues which refused to lie down. He had done it time and again, and here, once more, he had tracked a sinister old story down to the right place and time, where (he guessed) it was due for resurrection.

The old man on the bed was pointing: “Sit there,” he gasped. “I need to talk to you, youngster. Can you answer me?”

“Yes,” replied Jegand, “we reporters can answer as well as ask.”

The voice from the bed rose higher, the last spurt of a dying flame. “You know what used to be said about my parents and about me?”

“I have heard stories, but it was all a long time ago, wasn’t it? So, Lek Graol,” continued Jegand cunningly, “what can be worrying you so much now, I wonder? You have led a good life, by all accounts; a life of self-sacrifice in which you have devoted yourself to the good of mankind. You have saved thousands of lives. Moreover, in times to come this foundation of yours will save thousands more.”

The reaction to these words confirmed the reputation of Lek Graol as a man who could not bear to hear himself praised. Jegand watched in fascination as the admired benefactor of humanity squirmed. The movements were necessarily weak, but the impression he gave was that had his strength allowed him he would be thrashing about.

Words came, words which must have gone through many agonized rehearsals.

“Suppose my parents cheated? Suppose they named me? Yes, what if they gave me the name I bear? Suppose it’s not the real one, the one I pronounced with my first sound, but, rather, a mere given name? All my life I have tried not to think about it. Resisted all thought of accusing them. But their situation was uniquely hard… they might have done it… and so, might I in actual fact be… not Lek Graol but… Liucgr Ell?”

The swelling panic in the man’s voice, and the desperation in his face, at last roused some pity in the hard-bitten reporter. “Come,” said Jegand to the sinking man, “you must know there is an easy way to settle a question like this. You really want to know if you’re Liucgr? If you’re worried about it, then no, you can’t be…or at least…” He interrupted himself then: for he saw that the sufferer’s breath had grown shorter.

Jegand peered forward: yes, the head having rolled slightly on the pillow, the chest had ceased its feeble motion.

Jegand finished with a murmur, “…At least, not in any way that could matter now.”