the shears of night

a tale of the phosphorus era

from Uranian Gleams

by Robert gibson

1: Flocking to the City

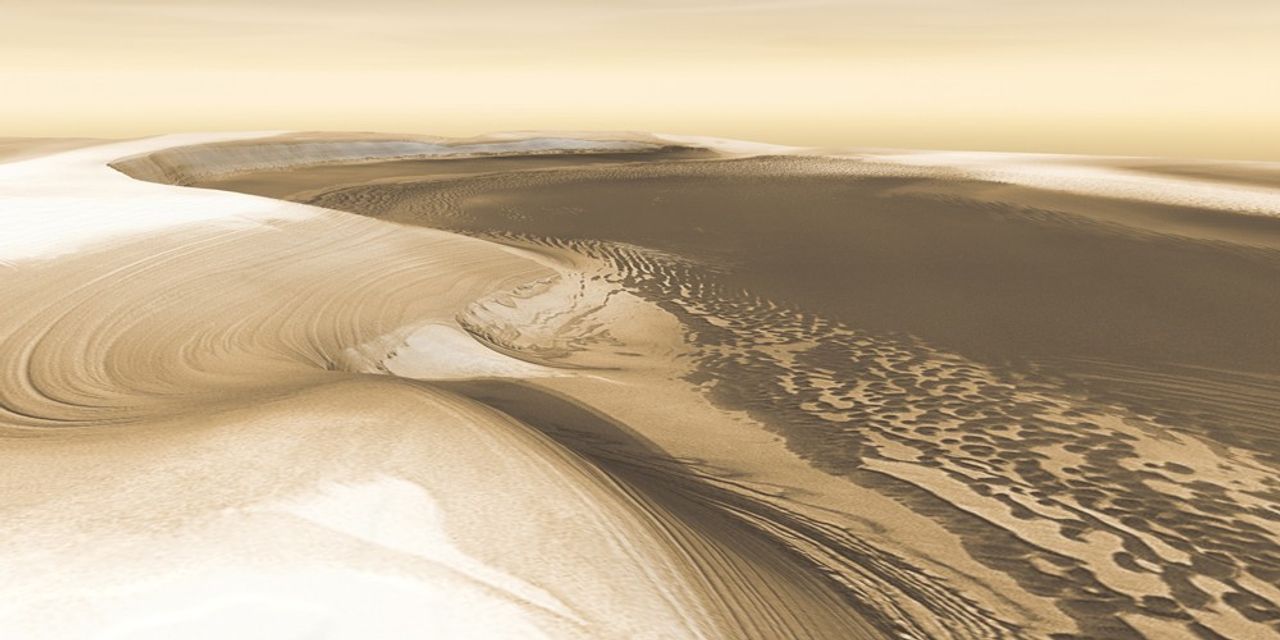

Night. Look down and see a dark plain crawling with lights. You are to understand that each light is a skimmer at close to top speed. It’s only the size of the picture that makes them seem slow.

We control what you see; we ensure that you understand, when we so direct you and not before. Otherwise the thing is equivalent to a lie – and we can prevent that, by force if need be.

Since the days when we were simply writers and you no more than readers, the relationship has progressed. Having placed yourselves in our hands, you must allow us to do what we like with you, till the tale is over. You are the rider on the Ferris wheel who cannot get down till the turn is completed. And think now, since we know about Ferris wheels, since we know your world in such detail, how utterly we must be masters of ours – so give in and accept our direction; do not struggle when a horror makes its approach; trust us to show you what you must do.

The skimmers are converging upon a city in concentric waves, like reversed ripples in a movie run backwards to show a stone un-thrown from the water; an effect unseen in nature but common enough in human affairs, for example when hordes are hastening to witness a trial.

You will not forget, during the telling of this tale, to give us credit for being truthful about ourselves. We story-tellers are natives of Ooranye, and as such we are honour bound not to “whitewash” our world: indeed our judgements are severe, for we are judges of judges, here where we sit at our safe distance from our predecessors of the Phosphorus Era.

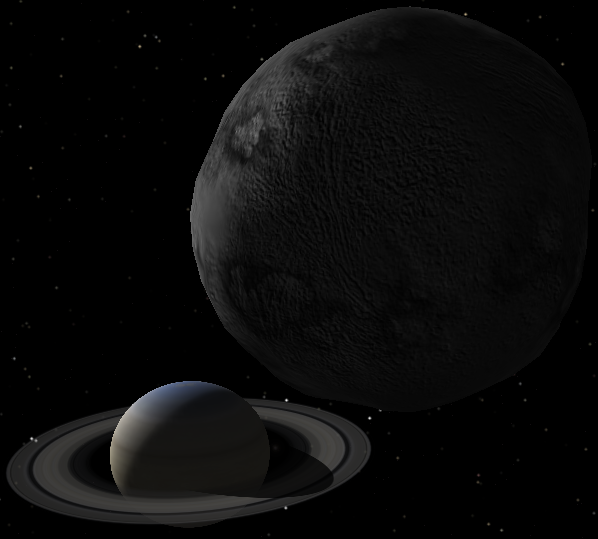

In the late days of that era, it was Vyanth that was the judge – Vyanth the richest and most populous of the great disc-on-stem cities of Ooranye.

Surrounded, for hundreds of miles in every direction, by the bioluminescent glow of cultivated fields, it itself outshone those farmlands, concentrating into itself the garnered light that was its wealth. And on 14,620,509 P, it had swept even more brightness than usual into its embrace.

We can make you see all this with your own eyes. For we now push you back across the span of ages, precisely to noon on Day 14,620,509 of the fifteenth era of Man on the giant planet, Ooranye.

First we force your eyes to stare at the pedestrians on the city’s rim. There they stand or stroll, there they chat, close to the edge, fifty yards above the surrounding plain. Then we swivel your sight to focus upon the watchers on the central towers. Aligning your brains, we next force the watchers’ sight into yours. Now you, like they, gaze at the pellets of light which are approaching over the plains.

You partake of the knowledge, that each brilliant dot is the skimmer of a foreign observer. They’re flocking here so as to witness the treason trial of Mulvu Xy, saboteur.

At the mention of that name – Mulvu Xy – we cause you to share the appalled, fascinated hatred of the people for the traitor in their midst.

An obscure nonentity before his crime was discovered, Mulvu Xy had then soon become the most notorious man in the known world. Still little more than a name, though. Most people had never seen him, never heard him speak.

We the back-haunting chroniclers can take you to see him this moment as he waits in his cell, but there is a difficulty: even if we allow you to read his thoughts, you won’t be greatly enlightened. A scrawny, unkempt man with pointy features, he sits back in his armchair, smiling faintly as if the impending horror were a ridiculous mistake, and in his mind there is the certainty, “I can get out of this.”

His accusers know better; know that he had no defence and no allies. He is surrounded only by enemies filled with righteous disgust.

(And we, with our special hindsight, can confirm that he shall not be rescued, nor acquitted.)

So far, though, Mulvu Xy, despite the doom that faces him, shows good spirits. He evinces no resentment, makes no complaint about any unfairness or harshness in the circumstances of his incarceration. Indeed he is comfortable enough, for the time being; the authorities are quite gentle in a way, quite lax as they serenely trust in the strength and power of their city. The government and people of Vyanth are willing for everything to be done openly; no precautions have been taken against espionage, no obstacles raised against publicity, and only the usual moderate measures are in place to safeguard the prisoner – it being correctly assumed that no one will want to rescue him. All extra efforts have gone into preparations for the great welcome which greets the spectators from foreign lands.

Throughout the city, scattered at various heights like birds’ nests in a tree, the illuminated hostelries, each on its own platform, flaunt their rooms and gardens.

Guides, stationed at intervals of sixty degrees around Vyanth’s rim, attend the landing-parks beside each of the ayashou – the airstreams which hoist incoming traffic onto the six main reception spaces. Like a two-way fountain each ayash continually spurts traffic up from the plains onto the raised city floor, and down in the reverse direction. Currently the incoming stream is by far the denser of the two sparkling lanes, as Vyanth blazes against the purple sky, imperiously welcoming the nations.

To those who journey towards it, the city’s glittering power first appears across a distance of over a hundred miles, as the summit structures, the aerial docks and spires, rise over the horizon. Minutes later as the incoming skimmers hurtle closer their pilots behold Vyanth’s concave-sided stem rising into view, like a sleeve and hand, bearing aloft the five-mile disc piled with multi-coloured forms: the lit hostelries, the branching walkways, globular palaces and helical towers.

Glorious reassurance for anyone at the end of a long and lonely voyage! Visual proof that humanity is able, even upon this vast and forbidding world, to build an unconquered haven for two million people.

And somebody has tried to destroy it. All the more do the visitors treasure the sight of it now. Many of these feasting eyes belong to reporters – those who might have been expected, by some defendants, to spread fair words, if anything might be said in the prisoner’s favour.

But the reporters, who in their home countries could have shown independence of mind, are here overawed by the splendour of the giant city. Even before they arrive upon its rim, they submit to its mind-set. Amid the vast influx of spectators the most rugged individualist is no more influential than a mote of dust, and we make this submission comprehensible to you the reader as we pull you through the incoming throng, to manoeuvre your invisible eye alongside one speeding skimmer among so many, to show the truth of what we say through the example of reporter Jad Lael.

Jad Lael is a chronicler from distant Pjourth who has skimmed over thirteen thousand miles to be present at the treason trial. The journey has taken him eight days.

Outwardly you see him, astride the vehicle, a wiry young man who eagerly leans forward with rapt gaze fixed upon the glow of his destination. Then we make you, Terran readers under our control, look inward, to share the awareness inside his skull –

Not such a shock as all that, is it? You meld quite swiftly, thanks not only to our skill, but to the context-awareness of Uranian humans.

Consider: they have never known any other world than their cold, dim, giant planet. Their species evolved there; they have no biological connection with Earth humanity despite close similarity in appearance. It would be natural to assume that their world is their norm, that therefore it can’t seem unusually large and cold and dim to them. And yet this is not the case. With that part of their minds which can lift their awareness above context, they know their own “norm” to be extreme, just as you do. By some objective cosmic standard they judge themselves to be immersed in some extra-vast mystery, which is your opinion, too. On this special level of their minds, therefore, they are not “used”to their situation; they are in a state of wonder, just as you are.

Thus the importance, to their restless souls and yours, of the reassuringly mighty, glowing city of Vyanth.

Like all educated Uranians, reporter Jad Lael understands that one must not expect too much of Syoom – the so-called area of civilization – which is, basically, a statistical concept. “The lands in which you have an over-fifty per cent probability of surviving a thousand-mile journey alone” – that is the strict definition of the area. Well, he has survived thirteen thousand on this particular journey. An instance of how the safety-percentage can soar well above ninety in good times. Yet, of necessity, patrols remain frequent and city-defences alert; for you can never take the resulting “civilization” for granted.

He reflects on this as he nears Vyanth, because here is a brilliant exception, an oasis of confidence, of glowing belief. The confidence trickles right down to the lower levels of his mind.

There it stops short of the bedrock, the stoppage point at which the people of Ooranye remain aware that they will never tame their world. Though they have evolved on it and know no other, they will never understand it. Jad has had plenty of personal experience to support this mood of pessimistic awe. All wayfarers know that they share the cold dim global vastness with so many bewildering forces and intelligences that the way of wisdom becomes the way of parrying, dodging, fielding, coping pragmatically with what one can not hope to understand.

But cities are havens – muses the elated Jad Lael as his skimmer begins to rise in the grip of the ayash –

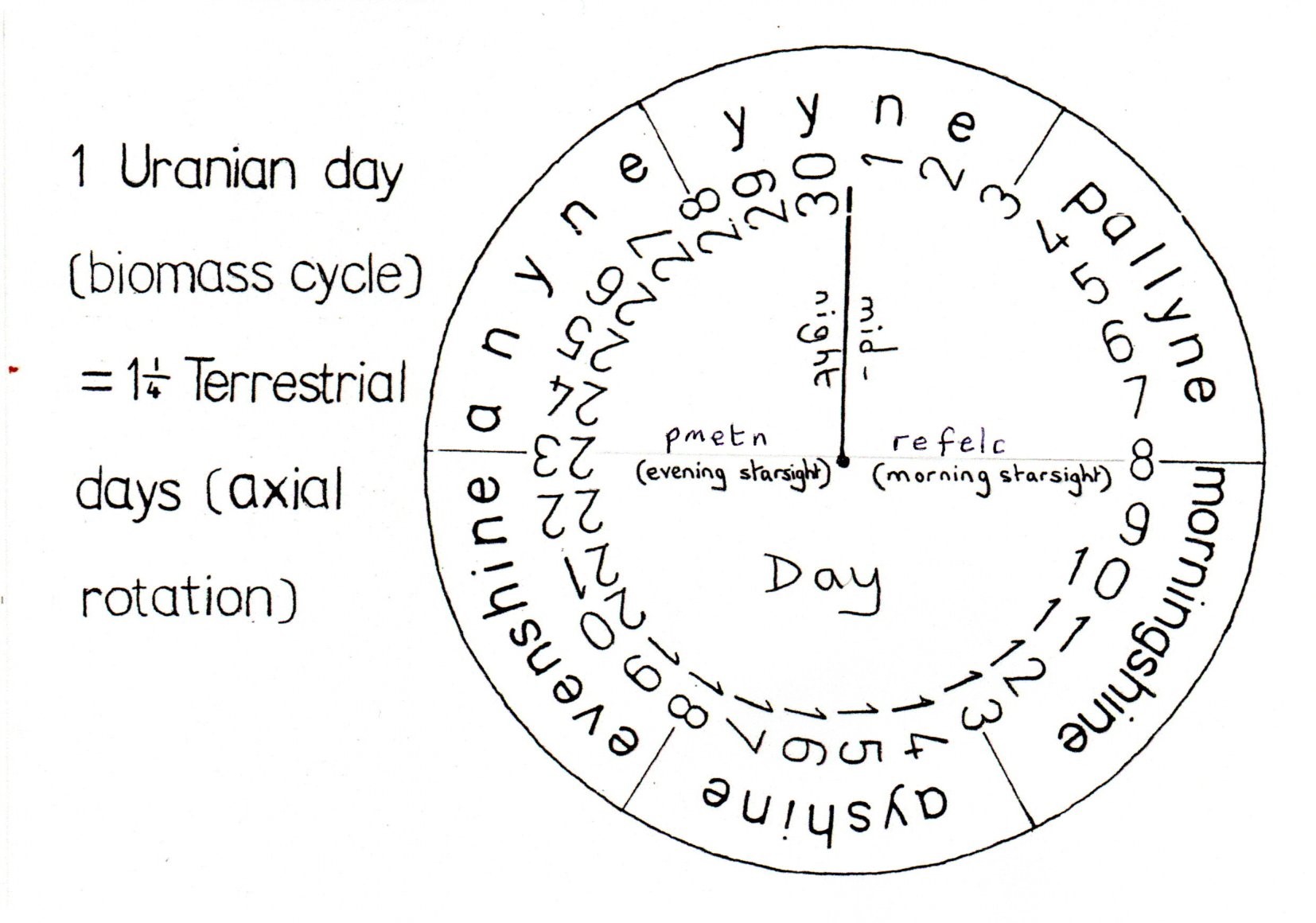

He sees further as the airstream lifts him higher until it treats him to a view of the entire extent of inner Maelv, the Bright Realm over which Vyanth reigns. In these exceptional lands – tended by hundreds of lifetimes of genetic engineering – the glow is constant: the bioluminescence does not pulse: the vheic crops do not dim and brighten in the thirty-hour beat which prevails elsewhere to define the cycle of day and night upon Ooranye. The exceptional empire of Vyanth shines uninterruptedly.

The brilliant vista is so strong a challenge to the vault of night, that even the bedrock of pessimism quakes, far beneath Jad Lael’s vision at the summit of the ayash arc –

But no. This heart of empire looks splendid, but even so, you simply cannot spread civilization all over such a world as Ooranye. The planet is too big, too intractable.

Civilization, moreover, means more than security; it means a shared system of values, and above all it ought to mean human solidarity in the face of the unknown. Jad reminds himself, in that culminating moment, of why he is here. Mulvu Xy has been accused of attempting to wreck a city. So you can’t even rely upon human beings… though surely no one man, however malevolent he may be, could inflict mortal damage upon this great ally against the darkness…

Past the summit of the airstream trajectory, Jad begins his descent towards the metal disc.

The compressed moment of vision is over, leaving him with a moral jumble of gratitude, sorrow, joy and dread. All local triumphs must come to an end some day. But one can hope that the current brightness will prove sufficiently robust, that it cannot cease by the action of a single traitor –

Instead, what would most likely cause the end would be a failure by the crop-scientists.

He has heard talk of this. People realize that agricultural experts aren’t forever going to be able to keep one step ahead of mutations in the crops. When these efforts fail, the continuous glow will give way to the natural pulse of the wild; the city’s resources will be halved; Vyanth will become poor and vulnerable to attacks from Fyaym – the antithesis of Syoom.

Fyaym – the “land under fifty per cent” – the area in which you have a less than half (usually a much less than half) chance of surviving a thousand-mile journey alone.

When that sad day came, Fyaym will bite a chunk out of Syoom, and the Phosphorus Era will be over.

Jad Lael is happily convinced that he will not live to see that day.

The ayash brings his skimmer gently down to a hovering rest a yard above the oalm or landing-park upon Vyanth’s rim.

He alights, his cloak flapping and billowing in the eddies from the ayash and the winds from the plains. Scores of other arrivals at the same moment are likewise stepping down from their aerial canoes. Each traveller’s first task is to see where nen’s vehicle may be stored. A guide stands by, repeating the words of welcome, “’Mjard. Here for the trial?” Almost always the answer is “yes”. Jad Lael gives this answer, whereupon the guide continues:

“Starts at noon. Palace of Justice two miles down Radial 3. You can park your skimmer in the vaults next to the Palace.”

“Thank you,” says Jad Lael, noting the direction of the guide’s pointing thumb, “but I prefer to walk.”

“That’s what I would do,” agrees the guide. “Get used to the dazzle.”

Jad Lael wonders a bit about last phrase. However, when you’re in a queue of events, you don’t request further explanation; you go in for brevity so as not to hold up the plot. If you’re a good Uranian, that is, able to boast the quality of lremd, of steering without bumping.

(Of course, we have heard that you Terrans have your own way of doing things, but we do not understand how – without lremd – you can possibly shape your lives into stories like we all naturally do.)

Jad pushes his vehicle to the city’s very edge. Here he finds the skimmer-bank into which the aerial canoe can be slid. He obtains a key and registers the craft’s number, then happily turns his back on the rim and heads inward.

Down Radial 3 he strides, heading for the hot brightness of the city’s hub. Pleasurably awed, he passes deeper into the polyhedral jungle of Vyanthan structures, immersed in the bath of radiance from metal hostel-trees, residential mounds and dangling palaces, overlooked by office-towers and airship docks, and threaded with the sparkling traffic-lanes which are bearing swifter travellers in the same direction. The thrumming dazzle never quite squashes his sharp reporter’s instinct. When I’m back home, he tells himself, just once before he forgets –

I shall remember one critical thing to say. Vyanth is a great place – but I wouldn’t exactly want to live here.

2: The Courtroom

The air cracked with random coughs, rustled with swishing cloaks, hissed with the shuffling of papers, droned with formalised voices, and, as an undertone to these human-scale sounds, the odder whispering crawl of a moving beltway forever circled the central arena of the hall, as if to hint the unceasing grind of the wheels of justice.

The prisoner sat at one of the foci of that elliptical beltway; the judge at the other.

The prosecutors, with no fixed abode, were wont to step onto the beltway one by one, to orbit both prisoner and judge. Like comets they approached the prisoner, swung past him and receded.

Woe betide one of those prosecutors who did not time his speech to pack the maximum punch at the instant of closest approach to the target. Those who made the tactical mistake of being either too long-winded or too concise were sure to be rebuked when their orbit carried them past the judge. So, pressure was on the accusers as well as on the accused.

However, the general atmosphere in the packed hall was one of unrelenting hostility towards Mulvu Xy – every Vyanthan spectator chewing the question, how could such a monster have been born of woman? Less partisan were the foreigners, perhaps thirty per cent of the crowd, but even they were swayed, their wits submerged and almost uprooted by the deepest currents of emotion. Take, for instance, Jad Lael of Pjourth. He had just about “gone native” during his walk down the avenue to the courtroom. And he was the sort who might, in other circumstances, have been of service to the prisoner; the helpful knowledge was there, in Jad’s head, but the memory of it had been cut off, and even if it had not been, no opportunity now existed to share the crucial facts.

Jad sat squeezed between an aristocratic lady from Nemyurur and a mountainous soldier from Contahl. His other immediate neighbours on the benches, he noted from the cut of their cloaks, were native Vyanthans. But with every minute that passed, he blurred these distinctions, thinking more in terms of “all of us” versus him.

The prosecutors droned on with the amazing list of apparently motiveless crimes.

“On 14,620,451 P you endeavoured to engineer a power-drain in the vaults.”

(Imagine if that had succeeded! Jad and the Vyanthans pictured it the same way. The treasure wiped out – resources depleted – freedom of action lost, both political and military – Fyayman pirates jump on our trade-routes the day after – )

“On 14,620,489 P you keyed a program for randomising the schedule of the freightways.”

(Imagine – economic paralysis – transport arteries clogged – city grinds to a halt – )

And then the worst so far:

“On 14,620,502 P you broke into Wayfarers’ Hall. There you were apprehended in the act of shuffling the signal-blocks of the Patrol.”

(Imagine if that had not been prevented! Wayfarers’ memoranda erased – dance of efficiency interrupted – intuition lost – knowledge of wilderness declines – safety statistic falls below 50 – encroachment of Fyaym upon Syoom – darkness falls on Maelv – )

The accusers pressed their charges, and the spectators in the hall added their dark incredulous stares, and noisier detestation rumbled from the crowds who were gathered outside, in the octagonal Clears where the trial was displayed on public screens.

Mulvu Xy sat, at his focus of the central ellipse, flanked by three guards to either side of him. His face was fringed by an untidy beard; he looked haggard, and his skin had blanched to a paler grey than that of most Uranians. Yet, considering what was likely to happen to him, he appeared to have his nerves well under control. While the accusations were hurled at him with wavelike regularity by the orbiting prosecutors, he assented monosyllabically to all of them, one after another.

The crowd would have been further amazed had it been able to see into his mind. For what frightened the doomed man the most was not the panoply of the law or his own probable fate, but rather a pretty little memory, sweet and uncanny, which had carried him through the hours of many a working day, making them fly hazily until his work was done.

The facts can only be brought together by our far later hindsight – lacking which, the audience heard, at first, only a senseless litany of misdeeds. Perhaps some sympathy for the prisoner might have touched them if at that stage he had been accused of some single enormity, but the spate of vandalism hardened their hearts. Increasingly their looks scowled the message: you deserve what’s coming to you, O soon-to-be-Interrupted Mulvu Xy.

Interruption impended! The opinion hardened: that euphemistically termed punishment was the only fitting doom.

This view was congealed into an immoveable clot by the last of the prosecutors: Gnaevona Hekka.

She, the Summariser, was a slim, glittering figure. All the court fell silent as she began to speak, as she glided forth onto the beltway. Her speech amassed conviction in all who heard. So weighty was her argument, so clear her conclusion that the misdeeds of Mulvu Xy were all aimed at Interruption, and Interruption must in turn form the penalty, that no other outcome ever seemed possible. She finally drew it all together:

“You,” she pointed at the accused, “were out to cause a discontinuity in the city’s metabolic flow; to snip the thread of its life.”

What an art it was, to marshal what you had to say, choose your moment to step onto the Track, time your piece so that the pith of your argument is spat towards the prisoner at the point of closest approach. And how effective it could be, especially when the prisoner could not resist the temptation to answer back with a proud, futile admission –

“I had my reason,” croaked Mulvu Xy.

“Tell the court your reason,” the receding Gnaevona called over her shoulder.

“Perhaps,” complied the prisoner hopefully, “it will not be a waste of breath to tell you.” He knew that the moment of maximum danger had arrived. They were listening, to allow him to condemn himself. Very well! His words tore the air:

“I voice the name not of Vyanth but of another, more tragic city – Hoog! Remember the hive-mind of Hoog! Remember it was detected far too late? Remember the grief it caused? Hard to imagine, that there must have been a time when it was young. Days when it was yet incomplete, intermittent, still deducible in moments of reflection. Easy it would have been, to snuff it out then; and perhaps some people did think of doing so. Perhaps some Hoogans’ thoughts wandered by chance into range of evidence of superhuman efficiency, of economic co-ordination far out of the ordinary, of excessive hours lost in trance, which could only mean that their city was evolving into a conscious organism. If those early thoughts had been voiced –

“But they weren’t. Nothing was done. Inexcusable to ignore what any psychologist can tell you - that consciousness is triggered by patterned complexity. Heed me! There comes a moment when a city’s awareness is switched on by the routines of its human components.

“However, although you admit it happened to Hoog, you can’t bring yourselves to admit that it could happen here. In fact I suggest your minds can’t form the thought. And this is because it is already too late.” Mulvu slumped in his chair and ended with, “I, however, did form the thought. I decided to act, to interrupt the pattern, while I still could.”

Silence gave way to a multitude of buzzing whispers. The next move was up to the judge. This was none other than the Noad – the Focus or Head of State – who was always ex officio judge in cases of treason. Fiarr Fosn, Noad of Vyanth, grey-cloaked and cadaverous in the glare from the hall lights, rose to look round at the “jury” – namely, the expressions of the audience – and then to deliver both verdict and sentence. His youngish, stern features faced the sea of eyes, and as he gauged the mood of the gathering the invisible crackle of their mutual regard bounced between him and them with an intensity which reflected his responsibilities in moments like these. His power hemmed him on all sides. His word was final and therefore it had to be right. His people were convinced that he was a great man – and so he was forced to be, by the inward-stabbing rays of their expectation which transfixed him with the compulsion that every word he spoke must be perfect for this moment.

“Mulvu Xy,” said Noad Fiarr Fosn evenly, “you have obliged us with the last piece of your mystery. I thank you for simplifying the case in this way. But your argument is invalid. The workings of any large city are bound to be systemic. They are thus always vulnerable to the kind of superficial comparison which you have made with the tragic case of Hoog.

“And speaking of vulnerability, the signal-blocks and memoranda which you scattered – you actually kicked them around, an unforgivable act – are of course open to such vandalism any time of the day or night. We cannot protect them by guards, for we do not operate them consciously. The trance state which you deplore, in the belief that it is evidence of our submersion in an urban group mind, is actually the only method by which such a complex system could possibly be maintained. We rely thus on instinct, and we have faith that the instinct is wholesome.

“It remains for me to pronounce what shall be done with you. Justice usually demands that the ill-doer’s motive be taken into account. Yet we cannot set the precedent of excusing or pardoning a deed like yours, a crime against the greatest fortress of light in our dim world. It was sheer luck that you were stopped before the harm you did became irreparable. To attempt such damage is to threaten more than Vyanth; it risks more general woe to the entire thin-stretched humanity of Syoom. The problem therefore is not how to temper justice with mercy, but how to conceive of a sufficient deterrent against any repetition...

“Fortunately, in your case it is particularly easy to make the punishment fit the atrocity. Mulvu Xy, I order that thirty hours from this moment you shall be Interrupted.”

A sign breathed through the hall. The audience once again felt nourished by its own trust in the Noad. Reassurance, as well as justice, had been achieved.

And what of the light they could not sense, the bath of radiance which impacts the scene from our eyes, the hindsight of future knowledge and understanding?

We happen to know that the judge was right in his argument: Mulvu Xy had been wrong to equate Vyanthan efficiency with sinister Hoog.

But as for the punishment… no. That was a wrong idea.

3: The Visits

Mulvu Xy lolled in the short-term comfort of his cell, maintaining his equilibrium, he knew not how. His hands gripped the wooden arms of his chair more tightly when he heard voices outside the heavy door. He could not make out the exact words, though he recognized the woman from the sounds… He did not wish to see her just then. Best to remain alone, for he was busy trying to work something out, something confusing: he was beholden to a power – a force – a kindness which scared him at the same time that it bolstered his hopes. We in the far future cannot reach back to reassure him, that it is not the mature, dangerous group mind, the existence of which he fears; no, it is the innocent murmur of the city’s fabric, trying to comfort him with proof of its own harmless infancy.

…Meanwhile outside the door, the generously proportioned Ommwa Plenn – the pale blonde betrothed of the condemned man – held herself straight as her uneasy escort explained the rules.

She was determined to confront tragedy with a no-nonsense air. With a curt nod she assured the guard: “Listen in by all means! In my view it is actually fortunate that you and your men shall hear every word which passes between that idiot and myself. Not only do I need to knock some sense into him, but I need it reported that I have done so. Then and only then, perhaps, can I appeal to the Noad.” The guard bobbed his head and ordered the rest of the detail to fan out. They took their positions round the platform which ringed their destination. Each man armed his laser at the door of the great sphere. Their chief thumbed the entrance switch.

The door slid open. Mulvu rose, smiling. “Glad to see you, Ommwa,” he said with a hand-squeezing gesture in lieu of being allowed to touch her. “And you, sponndarou [gentleman warriors], make yourselves at home and help me share this cell’s luxury, to which I am unaccustomed.”

“So, you freak,” stormed Ommwa, advancing upon him until the chief guard stepped forward and took hold of her arm, halting her a couple of paces from the prisoner. She ranted on: “Giving the Noad no choice but to treat you like an exhibit in a zoo!”

“You understand a lot of things, don’t you, Ommwa?” nodded Mulvu peacefully. “About the rarity, the unnaturalness of crime, here in Vyanth.”

“Oh yes, I understand things, I just don’t bother about them the way you do.” Her voice quavered: “Retract it all, Mulvu, please! Claim temporary insanity – even if I know it’s permanent – and throw yourself on the mercy of Fiarr Fosn – for my sake – please…”

“Ommwa, believe me, the Noad won’t weaken.”

“He’s human! And he knows that in thirty days we two were to stand in front of the Jommdan mirror to make our marriage vows.” She checked herself, quelled the wail in her tone, and made it hard once more: “But for your stupid, selfish, incomprehensible –”

“We’ll still stand in front of that mirror,” soothed the prisoner. “One day. At any rate, I intend to keep the appointment.”

She glared at him in frustration.

He went blithely on: “Our troubles, I suspect, will be over by then. No one can be Interrupted twice for the same offence, you know.”

Rage and admiration mingled in the look she gave him then. She quivered, for part of her wanted to hit him. The guards, sensing this, closed in.

At that point a second visitor stepped in through the swishing door, accompanied by yet further guards.

Tarl Hemmg, a tall, craggy, middle-aged wayfarer, greeted both Mulvu and Ommwa as friends. Bluntly he addressed Ommwa:

“Have you told him about the petition?”

“I was leading up to it.” Her tone became, for the first time, defensive.

“Petition?” demanded Mulvu in an ominous voice. Suddenly it was as if he had not been fully awake before. A new harshness glared from his eyes.

“Yes,” she began, “we have collected –”

“Don’t tell me,” and the prisoner’s voice shook, “I can guess: some softheads want to dilute the power of the law even though they believe that I was justly condemned. If you or they think that I shall ever accept a pardon – think again!”

Ommwa drew breath to shout him down. Tarl Hemmg pinched her arm. “Let me try telling him,” he whispered.

Mulvu, observing this by-play, snorted: “The philosopher!”

“Yes, the philosopher,” Tarl stated. “Let me ask you – even if you don’t immediately understand the significance of my question –”

“Go ahead,” growled Mulvu.

“It concerns a line of research which has more or less petered out, and I wonder if you understand why. I’m talking now about: matter-transmission.”

“I fail to see the relevance. Matter-transmission? What –”

“Every time it has been tried,” Tarl ploughed on, “every single attempt from the Lithium Era onwards, it has always been abandoned before it could ever become popular as a personal transport system. Do you realize why?”

“The expense, I suppose,” shrugged Mulvu. He felt a headache coming on, an almost welcome ailment, a fog of triviality. These people who had invaded his cell – it wasn’t worth worrying about them. The only development he need fear was some new avenue of insight. Such as might disturb the balance he had achieved, the balance which was all that kept his courage up as he awaited his doom. Insight! He hardly need fear that from this silly conversation… but this thought was interrupted by Tarl’s angry reply.

“Expense! If you think that was the reason, you don’t know flunnd about it.” Tarl’s voice became dry as crunchy bone. “Think about it for thirty seconds, will you?”

Mulvu put on a thoughtful expression and counted off the seconds with sardonic patience. “Sorry, time’s up and I still don’t get it.”

“So maybe you think it was a viable idea. Matter-transmission: a convenient, fast way to travel? Just scan the body, particle by particle, then dissolve it and beam the information to a receiver, a few thousand miles away perhaps, where it builds an identical body, identical to the last molecule and the last memory, and you assume the person at this other end is the same person! You’d go in for that, would you, Mulvu Xy? Without sparing a thought for the implications? The old body which is vaporised in the transmission chamber – it somehow passes its identity on, does it?”

“I see now what you’re driving at,” admitted the prisoner, and scratched at his beard.

“Then you see how serious this is? You get the analogy? You see that Interruption must be death?”

“Not necessarily. Perhaps the soul – the qualitative dimension of man – survives as if carried along the beam.”

“Wishful thinking.”

“Not if this ‘soul’ is linked to a brain-pattern in a way that’s independent of location.” Mulvu actually grinned; he quite enjoyed this type of argument. “In which case, there’d be no interruption of identity after all. Hmm… so what I’m saying – what you’ve led me to see, though you didn’t mean to – is that matter-transmission might well be harmless, since disintegration followed by reconstitution would not be equivalent to identity-interruption… an interesting point.”

At which Ommwa and Tarl gave up.

The visit did not quite end then, but both visitors realized that they could not defeat the courage of the little man who sat there debating the “interesting point”.

The furthest he was prepared to go, was to write a letter to Noad Fiarr Fosn expressing regret for the destruction which he, Mulvu, had tried to cause. He would not admit that he had been wrong, but he did admit that the decision to damage the great city of Vyanth had been a painful one… “The part of me that admires beauty above all else,” he confessed near the end of his letter, “makes me glad that I was defeated.” And then he spoilt it all by adding: “Illogically glad – for I know my plan was right.”

After this, just one more task was left to him. Another, far more important letter remained to be written.

4: The Letter

My dear Self,

They are coming to fetch me in four hours. This leaves me time to write this to you – to the Me who will be rubbing his eyes and looking around in freedom on the morrow.

Of course these words may be unnecessary, but just in case your sense of identity needs a nudge to make it fall into place, I attach a summary of the arguments which ought to convince you that one’s self can bridge the chasm of interrupted consciousness. Cast your eye over it now. Done that? Good. You must now surely sense the continuity, at a deep enough emotional level. The mind is transcendent. And please don’t dismiss this as wishful thinking; don’t get too tough, Mulvu Xy. Give positive thinking a fair chance. Consider: if I have sufficient confidence to dodge the terror which would otherwise seize hold of me, surely you, my dear self of tomorrow, can achieve the same. And the proof that my confidence is real, is that I have made no effort to escape. As a matter of fact, certain opportunities of escape were offered to me; yes, there are some sensitive souls in the Noad’s entourage, even including one member of the corps of guards who has hinted to me of ways out of here. Ways by which certain personnel might be hypnotised, ways by which I might be smuggled out, disguised as a reveller in the night; for life in this city is getting heated, and some have whispered to me that the Noad himself would not object if the Interruption were itself interrupted; does that mean that the logic of retribution has rendered him faint of heart? It’s possible; Noad Fiarr Fosn seems to me to be staggering under an invisible leaden cloak, namely the future that weighs on him: he’s an over-achiever, young for the post he holds, and I’m not the only one who suspects there’s no ceiling to his ambition; some day, mark my words, he will leave Vyanth and grasp a higher destiny – but meanwhile he could do to be bled of some pressures here… such as squeamishness about what must soon happen to me. Well, I shall not oblige him by entertaining any cowardly notions of escape.

I am a patriot to the last. I will take what is coming to me – in the name of the good old laws of Vyanth.

See you tomorrow – in the mirror.

Mulvu Xy.

5: The Punishment

Some dark mauve polygons of visible night loomed above Kioll Octagon where the multitudes waited to see justice done; but two-thirds of the sky was hidden, for the glowing lattice of city structures heaped itself highest in this central zone. Nevertheless, the very brightness, the throbbing vigour of the cityscape itself, brought contrastingly to mind the dimness beyond… the dimness, Jad Lael reminded himself, into which he would soon depart. He had achieved little on his visit to Vyanth. As a reporter he had learned no more than anyone else about the trial. Well, he was no investigator, merely a humble observer and chronicler of a public event. His one remaining task was to record the punishment of a traitor, execution of whose sentence was about to be carried out.

He and the rest of the crowd encircled a space with a platform at its centre. A bed had just been wheeled up onto the platform and now the mood of the crowed tautened. Dissatisfied with his own efforts so far, Jad Lael began one last attempt to get a special angle on the event which was about to occur: he elbowed his way towards what looked like a small knot of friends of the condemned man.

One tall, bitter-looking fellow was jogging up and down, to keep warm or to contain a desperate impatience, but he subsided as he noticed Jad pushing towards him. The man nudged the woman who stood next to him, and put an arm around her shoulders. They both faced Jael.

He said in a low voice, “Jad Lael, reporter from Pjourth. I saw you two at the trial. Can you tell a stranger what is going on?”

“I am Tarl Hemmg, and this is Ommwa Plenn. What do you find so hard to understand, stranger?”

“The jargon of punishment here. Why do they call the death penalty ‘Interruption’?”

Tarl grimaced, and quoted, “ ‘When in Vyanth, think as the Vyanthans think.’ The body of Mulvu will continue to exist; after eight hours it will be inhabited again. That’s their excuse for not using the word ‘death’.”

“Look,” said the pale woman, “here he comes now.” A slight, lonely figure had been pushed up onto the platform. They watched as he was shown to the bed and was signalled to lie down.

With a sob the woman continued, “Look, Tarl, he’s hesitating; he’s not so brave after all – he understands really.”

“We can’t be sure of that, Ommwa,” soothed Tarl. “His stance may be political, even now. But he’s too far away for us to read his face. You’ll have to take his courage on trust.”

“Ah, but I knew,” she muttered, “I knew all along, that at the end he would see it was all for nothing.”

Jad Lael, stung with pity, intervened with a suggestion he knew was no good. “I can at least take back word to Pjourth, that an injustice has been done.”

They shook their heads. “Thank you, but no,” sighed Ommwa. “He would not have been interested.”

Tarl said, “Hush!”

The condemned man was making his speech from the bed. His words drifted across the Octagon in an amplified blare. “…wider perspective… I can now see… part of a to-and-fro… no complete hive-mind yet… apologise for acting too soon… you people must look to the future…”

Then he stopped, for otherwise he would have been silenced by the hooded pharmacist who now approached the platform.

The pharmacist bounded up the ramp. Ommwa and many others turned their faces from the sight.

Tarl swore violently, “The stupid narp, for a moment I believed he had repented…”

The hooded one extended a fist. The fist opened, to show that it contained no last-moment pardon, but instead the dreaded little white capsule. The other hand reached forward, holding a glass of water. The crowd caught its breath as the prisoner obediently took both objects.

After it was all over, Jad Lael carried the scene in his mind’s eye, away with him as he walked to Vyanth’s rim, slid his skimmer out of store, mounted it and manoeuvred himself into the ayash, soared up and out and then down to skimming level and sped away across the plains.

The zenith was black with night, but for some hundreds of miles the lower air remained lit as if by day, stained bright with the glow from the rich fields of inner Maelv. “When in Vyanth, think as the Vyanthans think.” In the encompassing glow of this empire the precept was easy to follow, even for a traveller from the other end of Syoom. In fact it was hard not to think as a Vyanthan, after having spent an entire thirty-hour cycle of day and night under the influence of that city. It made it seem a normal way of living one’s life: to keep awake the whole time, in a state of never-ending uninterrupted consciousness, albeit muted by the trance of work-routines…

At length, however, Jad Lael reached a shimmering boundary, a wall of pallor between bright air and dim. He shot through this “attitude-pause” at two hundred miles per hour. Suddenly he found himself back in the ordinary night air of the wider world.

The memories in his head took on a modified meaning.

The change made him laugh.

Pity he hadn’t stayed a bit longer to greet Mulvu after he’d woken up! So much for the Vyanthan penalty for high treason! All that emotional agony, and then… but of course anything, even a harmless thing, can serve as a deterrent if people are sufficiently scared by it. So, if Vyanthans spend every moment of their lives in that opinion, it must fulfil their requirements for law and order, to punish a traitor with a sleeping-pill.