the worm of poleva

a tale of the niobium era

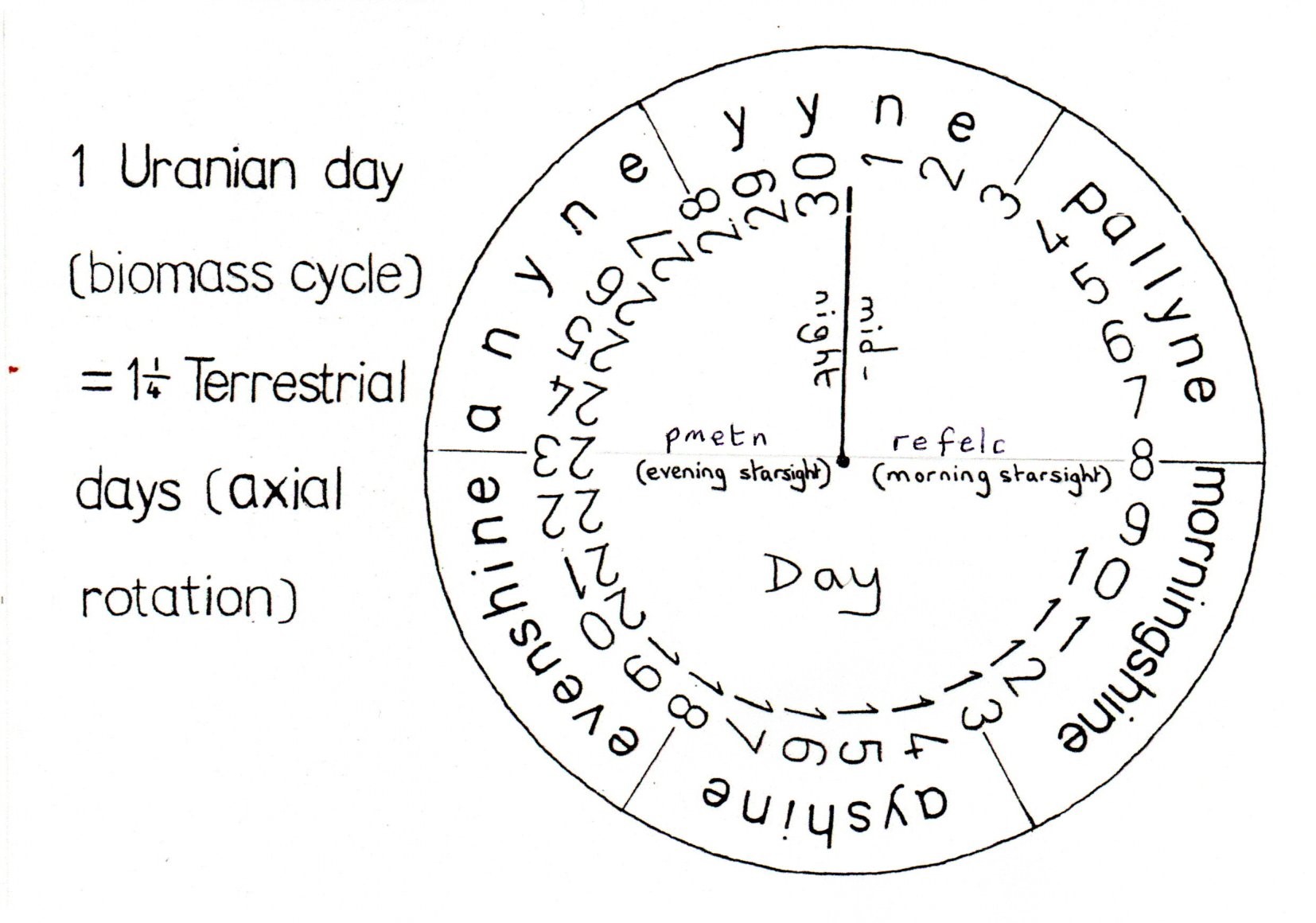

from Uranian Gleams

by Robert gibsoN

Prologue

When Nature reclaims a ruin, crumbling the artificial structure, reducing it to an uninhabitable mound and overgrowing it with weeds, we can say that she has retrieved the object’s status as a natural feature of the landscape. Her weapon of erosion has won her a battle.

Occasionally, though, the engagement can be decided another way.

On the giant planet Ooranye there was one artificial structure so enormous that it could not be comprehended by any human economy. The culture that built it failed to assimilate it, and it became an independent landscape feature; on any historic time-scale it was as indeclinable as a mountain range.

This was the Great Wall, older than records, and never owned by any single power. Even its pre-Cycle builders must have lost control long before the project was finished.

Once in a while, when funds allowed, and other matters did not compete too strongly for the attention of the government, the city of Contahl achieved a temporary ascendancy over part of the length of the Wall. Troops cleared its passages and rooms of Gedar submen, driving the savages from their nests out into the Fyayman plains beyond. During such operations, skyships floated overhead, firing down to sweep these and other less humanoid foes from the Wall’s wide summit.

During most of Contahl’s history its citizens have regarded the Great Wall not as an artefact but as a planetary feature no less perilous than the ocean of Fyayman night which lies beyond it; occasionally, though, they have experienced more confident times, of ambitious expansions of their control, during which their attitude to the awesome structure has changed. In such periods it begins to be seen as a possible defensive boundary, and, in a fit of memory, the government recalls that it has the right to occupy and garrison at lease some fraction of the ten-thousand-mile length of the Wall.

A circumstance of this sort occurred during the reign of Noad Govasswa Hayt, in the middle of the Niobium Era, the forty-first era of civilization upon Ooranye.

We see through the eyes of Gengr Axtain, a young wayfarer who has volunteered for service on the Wall:

Leaving his skimmer parked on the plain, he approached the nearest of the stairs set in the Wall’s side. Told that every place in the garrison has been filled, he nevertheless had come to look around.

He could see no one and nothing except the huge vertical structure itself and the contrasting flatness over which he had travelled to get here. He could eke out this basic view with a few known facts.

The Wall runs straight: a slash of order cutting through the chaotic borderlands of Fyaym. On average six hundred yards high, and one hundred and sixty yards wide, it is porous with chambers, corridors and the ancient, pre-human luxury apartments adapted nowadays to comfort the modern exiles manning this rampart of civilization. Along the top runs a line of observation towers a little more than a mile apart. They seem, and are, incongruous; their small addition of height hardly affects the vantage provided by the wall itself. Indeed they are not part of the original structure but were added by humans, in the course of some ancient power-struggle upon the summit.

Gengr was not surprised that the scene appeared to be deserted. He knew that the attention of Contahl’s garrison was likely to be fixed upon the Wall’s further side. Confidently he began to climb.

He zigzagged upwards back and forth until he came to an open door at about fifty yards’ altitude, where he first encountered some members of the garrison. One sponndar stood with laser drawn, and required Gengr to give an account of himself. The soldier then spoke into a transceiver, broadcasting Gengr’s description, and waved him in.

Gengr was surprised at being accepted so easily. He was here uninvited, after all. “You’re not worried that I might be a spy, an enemy?”

Before the soldier could reply another voice spoke from further in; Gengr had been overheard by an officer.

This man, seated writing at a desk, looked up and with a superior smile remarked, “Too much security is as dangerous as too little.”

Gengr had approached, but now he stopped, uncertain.

“How so, sir?”

The officer waved an arm and said, “After all, what of the beings who built this thing? Where are they now? What good did ‘security’ do them?”

“Ah, you mean they relied on the Wall too much, sir. But then, perhaps they were insufficiently vigilant,” suggested Gengr. It was a bit of a pointed remark, he realized when it had left his lips.

“Well,” chuckled the officer, “we’re vigilant enough. If you turn out to be an enemy, you’re welcome – we’ll thank you for the target practice.”

Gengr laughed, “I’ll have to disappoint you there, sir. I’m just a citizen, asking for a view from the top.”

He resumed his ascent. It was like climbing a mountain. No elevator shafts had been inserted into the structure of the Wall. Presumably, the pre-human Builders had not minded this; it was one possible clue to their nature – they may have been winged beings, or, perhaps, controllers of gravity. Maybe, maybe, maybe… a dumb reminder of how little we know of previous Great Cycles, thought Gengr. But then, we don’t need to know. In fact there isn’t such a thing, really, as knowing. That – surely – is the secret of the builders of the Wall.

Finally, after a restful interval spent in one of the garrison canteens, he attained the top floor and the last stair. From this he emerged at last onto the Wall’s summit. He seemed to be standing on a cream-coloured road in the sky. Low battlemented parapets to either side were all that reminded him of the truth. This was one of the undamaged sections, smooth except for the hardly noticeable addition of the observation towers.

A few sponndarou were in sight but he avoided them, uninterested in meeting warriors at the moment. He wished to commune with the vista alone. He strode to the far side, to look out over the sinister Fyayman plains, those outer immensities lapping against civilization. The air in Fyaym might be bright during daytime, every bit as bright as it gets in Syoom, but night reigned in the soul – the darkness of the unknown. Gengr after a long stare wandered back to contemplate the country on his home side: recently pacified lands, glowing cultivated fields, well-tended roads which stretched back five hundred miles to Contahl itself.

Fyaym out there, Syoom over here. The Wall in between. It was a contrast which fired the nerves. And yet Gengr, though he almost staggered under the weight of awe, suddenly realized that he was no longer inspired by the prospect of service upon the Wall. No, it was not for him. Instead, he would stride far beyond…

That was the surprising lesson he had learned by coming here.

For the time being, this stretch of Wall has been won, he reminded himself. And I know something of the expense; I have seen and heard official figures quoted. I can tell that Contahl has not the resources to keep up the garrison forever. As for mounting operations in the land beyond – to extend our empire deeper into Fyaym – that would be a futile project. Doomed to costly failure.

He guessed that a few attempts would be made, and soon abandoned, defeated by the numbing infinity of the task. Meanwhile he, Gengr Axtain, would enhance the empire in quite another fashion…

Slowly he descended, enjoying his new sense of purpose. He left the ancient Wall, his boots once more crunching the gralm as he walked across the plain towards his skimmer. He mounted and sped away homewards.

He reached Contahl in two and a half hours, but it then took him as many days to obtain an audience with the Noad. In view of the many duties devolving upon her as Head of a State which had just expanded to its natural frontier, Govasswa Hayt was an extremely busy woman. Gengr knew this, yet he was simple-mindedly confident that soon he would become one of the matters she was busy with – and he was right in this; a simple man who had allowed an idea to get lodged in his head, he was too naïf to fail.

“Brrrmph… I like your idea, young man,” said Govasswa Hayt, pacing the audience chamber, her grey cloak swirling about her stocky frame. Gengr noted that at each turn of her walk she looked at something – a screen, an indicator, a window. Multitasking, from moment to moment. “Not that I’m keen,” she added sternly, “on the cost to the Treasury. But,” she continued half to herself, “I can think of no excuse to turn you down…” She halted and swung round to face Gengr Axtain. Her sharp glance swept his pleasant face, as he stood patiently awaiting her inevitable verdict. She smiled faintly as she read his easy stance, the deportment of one whose ambition burns steady and serene as a main-sequence sun. She nodded with decision.

Noad in all three Syoomean tongues means focus. Govasswa Hayt was a middle-of-the-road Focus of her city. She avoided both extremes of political style: she had not arelk (the rigidity of a despot) and nor was she a Fyffy, that legendary buffoon who (if the story can be believed) actually went around soliciting for votes. She was a ruler of mature judgement with an instinctive focus upon the lines of political force, and as such she voted in her mind for Gengr.

She was old whereas he was young; she a wily Head of State, he an innocent adventurer; but the patriotic flame burned bright in both their souls.

“Return to the palace in five days,” she commanded, “and, barring emergencies, you shall have your krematar.” (Authorization, immediatization.)

No emergency intervened. These being heady days for the Contahlans, a mood of heroic generosity infected the people’s hearts; their pride swelled at the vast expenditure proposed, as an old name returned to their tongues: “Poleva”. Yes, let us send comfort to long-lost Poleva, although we shall never get anything in return for the fare, except for the glory of the deed. The very letters of the word “Poleva” resounded with the glamour of past catastrophes. While Contahl was a frontier city, close to the boundary between the light of Syoomean civilization and the darkness of Fyayman chaos, Poleva was a different case, far beyond the frontier; a lost outpost in the deeps of Fyaym. Lost, that is, apart from one tenuous link – the matter-transmission Portal.

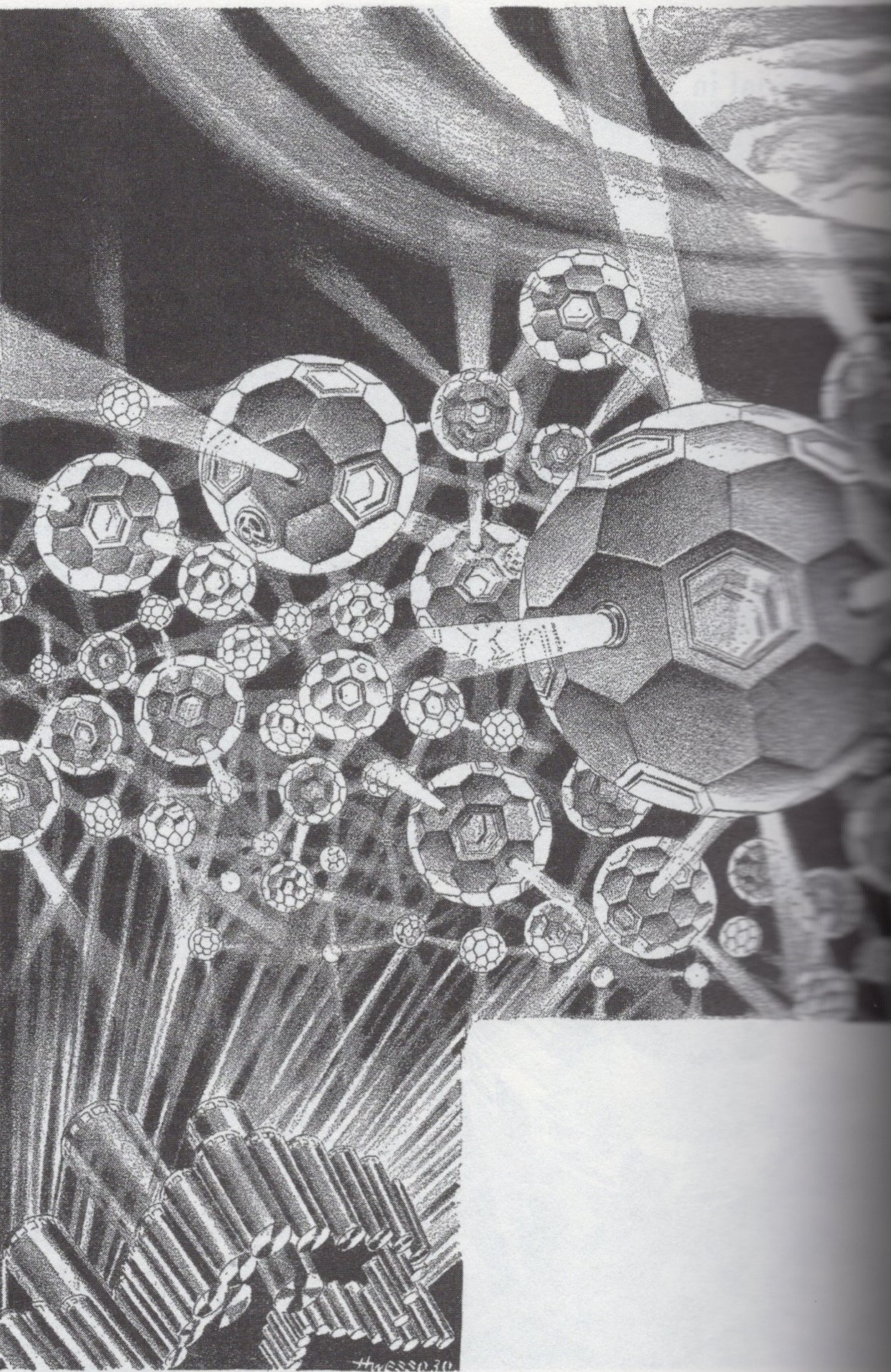

The Portals endured, though nowadays their use was almost unheard-of. Their physical fabric survived as one of the mighty works of the Phosphorus Era, the period when builders notoriously drew upon limitless supplies of energy looted from the Other Dimension, Chelth. No Uranian would dare try that game again, but modern man could still profit from his ancestors’ robbery of Chelth, twenty-six eras later: after all, the great disc-on-stem cities of Ooranye had been constructed with the aid of the stolen power.

And just as the cities still lived, so, likewise, it was still possible to power the Portals. However, the price would now have to be fairly paid. Uranian resources must henceforth suffice, since access to Chelth had been discontinued forever.

If Contahl were willing to pay that price, it could flash a living body to Poleva, eighteen thousand miles distant, instantaneously attaining an objective which lies so deep in Fyaym that no one would try to reach it overland.

Gengr Axtain, and the officials whom he talked with, believed in the likelihood of finding people still alive at the other end. Records in the Contahlan vaults alleged that the Portal network had been used in the Phosphorus Era for quite significant movements of population. In fact, it had perhaps been a serious attempt to tame the vastness of Ooranye. They had thought to web the entire globe in a network of cities, finally to bring about the triumph of Syoom over Fyaym.

That attempt had of course been doomed. The plan could never have succeeded: first of all because Ooranye was too big and four-fifths of it was Fyaym; second, because the destruction of the Great Fleet in the global nightmare which ran down the curtain upon the Phosphorus Era left no one with any spare energy for aught but survival. Whole populations had thus found themselves stranded in the Fyayman wilds with no means of return. But the backwash of history did leave some achievement in its wake. Outposts such as Poleva, Olhoav, Nusun and Koar survived.

This was known in Syoom because on rare occasions the Portals had been reanimated to keep in touch with the outposts. Though no private individual was rich enough to activate the transmitters, governments – when flush with resources – might send news, supplies, or even an emissary.

The generous Contahlans approved their Noad’s decision to transmit Gengr Axtain to Poleva.

1: Arrival

The instant the field switched on, the crowd of leave-takers became nothing more than a milky after-image on his retina. That sight, of their arms raised in farewell, would have to suffice for evermore.

One pressured moment of illusory speed and the squeezed-out pip of identity that was Gengr Axtain had jumped over the map from point to unrelated point. Next he was staggering on the disc at the receiving portal. An imaginary howl rang in his ears - a protest from the cheated fabric of space-time.

He was in the open, under a starry sky, a little way outside Poleva. He was seeing that city from about half a mile out. Out here the installers of the transmission network must have been too nervous to site the receiver within the city boundary. Gengr did not condemn their caution, but neither was he happy at being deposited even a short distance outdoors in the far Fyayman wilderness.

He dropped warily to the ground. Then, after a minute, he straightened, for he noticed he was, after all, safe within a kind of circuit formed of glass ramparts that appeared to ring Poleva’s fields of vheic. The plants themselves, reassuringly familiar, waved in the breeze; only the sky with its strange stars told him, “You are on the other side of the world”.

Poleva itself, rising in the midst of its cultivated area, loomed like an oversized half-egg, criss-crossed with struts and lines connecting its geodesic panes. Its predominent glow was pale yellow, which gave it a kind of paradoxical dim brightness against the black sky and the violet horizons. Gengr Axtain stared in resigned wonder at what must henceforth be his home. This was a city actually built on the ground, like his other home, ancient Contahl itself. That at least was one continuity: he would not need to get used to a disc-on-stem.

For the builders of the Phosphorus Era, mighty though they had been, had not been able to use their up-raised disc-on-stem design for their Fyayman outposts. While power was free in those days, the supply of iedleis, the ultimate metal, was not unlimited. What there was of it had had to go into the construction of the metropolitan cities of Syoom. Here, on the other hand, they’d had little choice but to squat their settlements down on the ground. Rash that might seem, out here in deep Fyaym, but what else could they have done? Gengr stepped thoughtfully down from the receiving platform.

With slow steps he walked along the road through the fields towards the gate. As he did so a hooting and clanging arose from that direction. Already, people were streaming out towards him.

They came on foot and on skimmers, and other skimmers swerved from elsewhere in the fields; no doubt his arrival must have registered upon every energy-detector in the city’s vaults as well as on every human eye that happened to be turned in the receiver’s direction. No citizen of this long-nighted land was going to miss the sight of the first visitor from Syoom for many an age.

Deafening him with greetings, the Polevans swarmed around him. They turned his entry through the gate into a triumphal procession in which he had to repeat his name scores of times on eager request. He was introduced to hundreds; his every reaction was scrutinized, devoured with avid stares. Each citizen seemed determined to share in the marvel and freshness of his experience, right up to his arrival at the globular palace which was hurriedly allotted to him. At its threshold he turned, with a trusting smile, and gazed back down the ramp at the buzzing cityscape while he waited for someone in authority.

A breathless laser-bearer no older than himself came forward to announce that the Noad of Poleva would certainly give him audience within the hour, immediately upon completion of that day’s tour of the urban defences. The youth added, “I am Berr Ucht, the Noad’s courier. I have been instructed to ask you what you would see in the meantime.”

“I would see everything! I’d climb a tower, right now if possible, to get a view of your country.”

“I heard that,” said a commanding voice. Gengr turned to see an older, taller, heavyset man striding towards them round the curve of the building. The courier departed smartly. Gengr and the older man appraised each other.

“I am Nekkon Lalldorpl, the Noad’s son. Because my father is not strong, I help him out with his social functions – such as welcoming a once-in-an-eon arrival from Syoom.” The corners of the man’s mouth turned down grimly. “Follow me: we have time to ascend the Rezram Tower.” It was the weight of jowl, decided Gengr, that caused this fellow’s statements to thump, to land like a posted summons on the mat.

“Rezram? Ah, a hero of old Syoom,” replied Gengr, and smiled regretfully when his comment went unanswered: apparently the reference meant nothing to Nekkon Lalldorpl. Perhaps anyhow it might be best not to refer to the culture of a hemisphere which he, Gengr, would never see again: he was here on Starside for keeps.

As they strolled, the newcomer gazed down from the heights of the walkways, down through busy levels of the urban lattice, to the city floor. Poleva thrived, obviously. However, at each main intersection in the three-dimensional maze, checkpoints were staffed by watchful guards.

Nekkon observed Gengr’s interest and said: “Spy-scare. Nusunian spy-scare rumour.”

Gengr asked, “Isn’t Nusun thousands of miles away?”

“I can see, you think it incredible that one Fyayman outpost should have any trouble from another. But our fear is, that if their city is failing, they may try to migrate here and seize ours. Unlikely but possible.” Anger had appeared in Nekkon’s tone. Anger directed at me, Gengr suddenly realized with a start of guilt. He’s highly intelligent; I must watch out. My expression must have told him what I was thinking: ‘these stupid squabbling outposters, gurgling down the moral plug-hole of internecine conflict while Fyaym waits to engulf them…’ Just then he heard a burst of cheering, and his guide paused to flash a smile at a group of arm-waving citizens who sped past them on a skimmway. “Well,” continued Nekkon, “how does it feel to be a celebrity?”

Uneasy with the other’s sardonic tone, Gengr tried to play up to it. “Not bad – if there’s no catch.”

“There’s a catch for you all right,” growled Nekkon. “The catch is, no going back.”

“Oh, I know that.”

“ – Unless,” continued the other, “you wish to attempt the return journey overland, alone! You certainly won’t find us stumping up the cash to operate the Portal from this end.”

“I’m not grumbling in the slightest,” replied Gengr, attempting to allay the other’s grumpiness. “In fact I had no guarantee that I would find a surviving city at this end at all.” He was not keen on what seemed to be implied by the other’s words. To suggest that he, Gengr, might blench from the consequence of his own decision to come here - ! He was only human; he was bound to feel some homesickness. And furthermore, as he thought about the general welcome he had received, he had the strong impression that the Polevans themselves yearned to touch Syoom, even if only vicariously by feasting on the sight of a visitor.

By this time they had completed the spiral ascent of the Rezram Tower. They went to stand at the railing. Frome there they gazed down over Poleva, and to the belt of fields beyond, and the wilderness of Fyaym beyond that.

Fyaym – the antithesis of Syoom.

Fyaym – the land where a lone traveller had a less-than-fifty-per-cent probability of surviving a thousand-mile journey (and, in deep Fyaym, a lot less than fifty per cent).

Fyaym – defined thus statistically, for that was the way to label the problem, and to label the problem was the most you could do on this giant world of unpredictable threats, disasters, crises and foes which were apt to appear out of the dimness at any time. Fyaym was sixteen hundred million square miles of untamed twilit peril, out of which absolutely anything might emerge to harrow the civilization of mankind; and Poleva stood deep within this unknown four-fifths of Ooranye.

From the Rezram Tower’s summit railing Gengr could see three terrain types. A canopy of dark green jungle stretched away towards one arc of horizon and, towards another, the contrasting wrinkles of a barren rocky area folded into ridges, one brown shade after another. In a third direction a bare plain extended to infinity.

He caught sight of a satisfied expression on the face of Nekkon Lalldorpl as this son-of-the-Noad asked, “Well now, man from Syoom, what do you think of all this?”

Gengr, for whom tact was not a strong point, had an impulse to pin down what was wrong in Poleva’s location.

“An enemy army could be at the gates before you know it.”

“Vigilance,” shrugged Nekkon, “is the only answer. Unless…” he paused, now scrutinizing the Contahlan closely, “one were to get help from Syoom…”

“Which you won’t. They could only just afford to send me – one lone body – through the Portal.”

“So we both know the worst,” smiled Nekkon. Then an odd, dramatic twitch overcame him. His eyes blazed, his jaw jutted. Theatrically, he seemed to grow as a laser appeared clenched in his fist. Cloak swirling, he brandished the weapon at the panorama of Fyaym. In that moment he symbolized for Gengr all the defiant heroism of the lost cities, the outposts, Poleva, Nusun, Olhoav and Koar, whose names echo like music in the mind.

What a renowned Noad this man could make – thought Gengr idly – at least as far as image was concerned! A pity it could never happen. The noadex – the office of Noad – was precisely the one post which the son of a Noad could not hold. Unless the taboo against hereditary monarchy had weakened out here in Fyaym…

“False hopes,” rasped Nekkon Lalldorpl as he sheathed his laser. “Those head our list of enemies to kill.”

They descended from Rezram Tower.

At its base, Ber Ucht waited to conduct Gengr to the Noad. Nekkon bowed curtly and took his leave.

Time, now, for the Syoomean emissary to meet the Polevan Head of State.

A cream-coloured wave, which rose from ground to thirty-yard crest, the Palace of the Noad shone modestly amid the crowded city centre. Exterior escalators fed in and out like veins to and from a heart. Gengr was told to go through one of these entrance tubes; he emerged from it inside a glittering suite with recording sensors sprinkled like diamond dust on every wall.

An elderly man sat writing at a desk. Reyeb Lalldorpl, Noad of Poleva. He looked up and his aged face beamed with the enthusiasm of a happy child. “I long to hear your story, Gengr,” he said mildly, gesturing to the facing chair. “Never did I think to receive this good fortune in my lifetime. I suppose we are mythical to you, and you of Contahl are no less a myth to us.”

Gengr sat. “I am relieved to find you and your people real,” he confessed, swayed into a chuckle, for the other’s obvious good nature made nervousness impossible.

“Oh, we’re all too real – we and the things which keep us busy. Too busy. I regret I was not able to greet you on your arrival. Nekkon has been looking after you?”

“Most effectively, Noad R-L.”

“You may think this strange, but it is precisely because he is my son, and cannot succeed me, that I feel free to load him with public duties. I can dump them onto him knowing that in so doing I am making no move to prejudice the succession… but enough of that. I am not so infirm that I need leave all the celebrations to Nekkon. Let us talk of Syoom, you and I.”

They chatted for hours, at the end of which the Noad scribbled some introductions for him – “not that you’ll need them,” he added – and wished him happiness in his new life as a Polevan.

2: The Roil

A woman sat at a desk inside a dome, itself fitted inside a cylindrical enclosure, near the edge of the city. Inside and out, the complex was well lit. The expenditure of energy to light it had caused some complaint – but, so far, the warden had been left to run her prison as she saw fit.

No longer in her youth, she remained attractive in a brittle kind of way: her features retained the tense beauty of a glass flower. Walking into her office, Gengr Axtain did not doubt for one second that he had entered the presence of the Daon of Poleva.

He had been warned by the Noad. “My successor, Polange Nsef,” old Reyeb Lalldorpl had confided, “has what one might call a hungry charm. It serves her determination to persist with unpopular schemes.”

Obviously this Polange Nsef woman was convinced of her own destiny; she must feel that she had some special vocation which set her apart, else why should a Daon of Poleva – heir to the noadex – choose the unappealing post of prison warden? To want that job, one must certainly be endowed with an original mind -

“Gengr Axtain? Glad to meet you at last,” she greeted him warmly enough. “Like everybody else I have been eager to meet The Syoomean!”

“Thank you,” said Gengr, cautiously.

“I expect you’ve been kept busy these past few days?”

“Yes, I’ve turned into a sort of city mascot, it seems. People are making the most of me, knowing that they won’t get another such specimen for an eon or so. You may wonder, Daon P-N, why I left my visit to you until last, but I assure you - ”

“Don’t worry – I’ve been busy too – but now that you’re here, I’d appreciate your view on my crazy idea of keeping prisoners alive.”

Warily he objected, “I never said it was crazy.”

“Ah, but others do, and you must have heard them.”

“I know you are bound to have your reasons," he said diplomatically, "but I can’t guess what they are.”

“You have no prison in Contahl?”

The ex-Contahlan grimaced. “We do have a prison, but only for malefactors awaiting judgement, or prisoners of war awaiting exchange. We do not have prison sentences as such. We have the death penalty, and the penalty of banishment. That is all.”

“Here,” remarked the Daon, “banishment would be a death penalty.”

“I see that.”

“But the main point is,” she went on, “what is the use of capital punishment as a deterrent, when so few people are afraid of death? Most of us, at this early stage in the Great Cycle, are in our first life; we know we have our second life to come, and perhaps even a third after that. Why should anyone be afraid to die?”

Gengr mulled this over. Why indeed. Death was merely an escape to another time. There were plenty of phenomena which could inspire fear, but they all pertained to life, not death. Phenomena such as injury, shame, responsibility for failure, or the many intrinsic horrors which needed no reason to be scary as they encroached from the borders of the unknown – they all ensured that Life, not Death, was the terrifier. “Yes,” he mused out loud, “our death ‘penalty’ is really just a means of clearing nuisances out of the way.”

“And it cannot be more than that; because the souls of the condemned get recycled, and this is known to all, so people do not, as a rule, fear the process.”

“So,” deduced Gengr, “you want to do something worse to them instead.”

“Loss of liberty,” nodded Polange Nsef, “is more frightening than death, is it not?”

Gengr thought about prolonged incarceration, and shuddered. “I’m with you there.”

“Besides, we cannot afford to kill able-bodied evildoers. Our population is small enough as it is.”

“You use them?”

“It’s not ideal but at a pinch, yes, they can be released and deployed as troops for defence. You must realize that Poleva is a beleaguered garrison with Fyaym the constant enemy, and every one of us may at short notice be needed to man the walls.”

“I get the picture; but are prisoners really any help?”

“Oh yes, if they only stay employed a short time.”

“And can they be given their freedom if they fight well?”

“Those who have undergone a change of heart, yes.”

Gengr did not say out loud, How can you tell? He simply raised his eyebrows. And then –

For some reason it came to him at this particular moment, that he would not for all the world do anything to hurt or offend this woman; the amazing thing, which he had seen make fools of many of his friends, had just happened inside him for the first time, and his whole outlook wheeled like an engine on a turntable, to face a new ideal. Polange Nsef – stunningly – had become his ideal.

The first effect of this stupefying change was to make him absurdly protective. He knew it was mad but could do nothing about it.

Her head, he noticed, was cocked to one side; background noises had diminished; ordinary, workaday sounds, which usually came in through the windows and doors, had faded into hush. Gengr held his breath. Then he almost choked as a scream tore the air. YEE YEE YEE. The scream of a siren. Polange rushed to the window. She tore it open and tilted her head upwards.

Gengr followed her and he, too, looked out, his uncomprehending eyes sweeping the cityscape while other windows in the building sprouted their share of heads and hands – many of the hands holding binoculars –

“Get your heads back in!” shouted the Daon to her staff.

She pulled Gengr back, and his heart thrilled equally to her touch and to the crisis, of which, as yet, he understood nothing.

Then the siren stopped, and now an eerie vast rumble could be heard somewhere up in the sky, drifting closer.

Polange breathe a word which Gengr did not recognize. She looked back at him and, while she spoke, he desperately tried to snatch at his wits.

“You and I, Gengr, can only hope and watch, for I am not on the defence rota for today. Anyhow it will all be over in a few minutes, one way or another.”

Still he did not understand. The din grew in volume. He told himself to use his eyes and keep his mouth shut.

A roiling brown border of a cloud-blob hove into view above the prison wall. “High, but perhaps not high enough,” muttered Polange. Gengr began to understand at last, and to estimate… The amoeboid shape seemed to battle with itself as it churned and bubbled. To the tense faces below, it gloated its power, terrifyingly poised to smite downwards, and Gengr froze as his capacity for belief caught up with the situation. Scores of Polevans on defence duty had scrambled to their posts; searchlights flashed on in the upper city; the Daon, seeing the look on Gengr’s face, assured him in some detail that in each fortified emplacement the defenders were ready to produce salvos of laser bolts, plus pressor beams to repel, force-blades to chisel, force-planes to shield. But though the bristling cloak of armament began to hum, the order to fire was not given! Understandable, perhaps. Well might the Noad hesitate, Gengr imagined. For were not all these measures mere pin-pricks, irritants which could further enrage the already frenzied cloud?

He tried to express this, and Polange nodded and shouted back, “It’s not one, it’s several clouds. Watch them fight each other.”

By this time their mile-wide bodies were in full view, entwined as they gulped and howled, emitting fusillades of blinding white bolts and broader lava-like spurts, much of which spilled down onto Poleva. Gengr shook his dazed head; this was life on Starside! He had never heard of any sentient cloud that possessed such a level of ferocity. At any moment he expected a full-scale exchange of fire between ground and sky, with ground overwhelmed.

That this did not happen, he realized after a couple more minutes, was due to the unintentional nature of the threat. The clouds were not interested, or not primarily interested, in attacking a human city. All that Poleva needed to do was to shield itself against the spillage of their fury. For this, the force-places produced by the defence-generators proved sufficient, though for several more minutes, after the echoes died away, Gengr marvelled that he was still alive.

“All clear,” said the Daon with a twinkle in her eye as if to say, now you see what kind of life we lead in this part of the world. “Excitement over.”

Gengr left the window and returned to his chair, hoping that his skin had not blanched overmuch. He was reasonably sure of the coolness of his outward behaviour. But – more urgently than ever – he knew he must find some definite role in Polevan life, to do his bit to thicken civilization’s thin front line in this remote land. Thus he’d show the people that he was more than just their mascot from Syoom.

Polange plumped down into her chair. “Where were we?”

Gengr rapidly faced the truth: this is the last of my introductions and, when it’s over, all the receptions will be over and I shall be on my own, a foreigner with no native skills, no particular excuse to see her again. The seconds were ticking away and his mouth felt dry. He wasn’t used to coping with the sense that the person he was talking to was of infinite importance. He had never met anyone of infinite importance before. It magnified the dread of every act. Now, on his part, nothing less than perfection would suffice. Awkward, that. His choice of words would have to be faultless. And he must at all costs do the right thing, whatever that was. Strange, how impossible life had become. It had always seemed quite easy before…

A buzzer sounded upon the Daon’s desk. “Excuse me a moment,” she said, flipping a switch with one finger. “Yes, what is it – I am interviewing the Contahlan –” An urgent voice gabbled from the communicator and Polange Nsef slumped in her chair. A look of misery appeared on her face. She snapped back at the voice, “Very well, wait for my orders – I take full responsibility –” She clicked off and stared through Gengr.

He leaned towards her, searching her shocked face. “Please – what happened?”

She signed, “There has been an escape. Under cover of this storm. The first successful breakout in my tenure as Warden. This could finish me.”

“Finish – ?”

“I can see (now that it is too late) how it must have been done… I must organize a search party, but –”

“I shall get them back for you,” interrupted Gengr. “Dead or alive.”

“You? Why you?” She seemed poised to laugh. “Are you raving, Contahlan?”

“You mean, Why me? Well, er… an outsider’s viewpoint – I don’t know – but here I am, for you to use.” He willed her to believe.

She straightened, “I’ll do it. I’ll commission you.”

“Thank you, Daon P-N.” How grateful he was for the aura of his origin on Sunside, for the magic of the name of Syoom! That alone could account for his successful persuasion. “I’ll not fail you.”

“You’ll need to know –”

Hustling, anxious to be underway before she recovered her senses, he broke in: “Brief me on the way to the departure point. The trail will be cold soon.”

3: “This is Fyaym”

The escapers (it was soon discovered) had made for the forest. Its near edge grew a few hundred yards from the outer vitreous ramparts of Poleva; into the dark green maze plunged Gengr Axtain, newly raised to the rank of zamur, followed by his nyr of eleven laser-bearing sponndarou.

The lasers had to be put to immediate use in order to burn a path through the foliage. Gengr and his followers wielded their shimmering blades with a hacking rhythm; it was such work, that within minutes some of the sponnds had to be recharged, even though the pursuers were following a trail previously hewn by their quarry: a path which, mere minutes after its creation, was becoming fuzzed and clogged by new growth. The vegetation grew not at a steady rate but in quanta: the crack! crack! of fresh branchings buffeted the men as they struggled onward.

Added to these discomforts were other unpleasant aspects of the forest – the noisome breezes set off by blower-stems, the pools of goo dropped by the sucker-plants, and the globular insectoids lurking as fake fruit inside hammock-sized leaves. It was a solace to Gengr that he was able, for a while, to maintain contact with Polange Nsef by transceiver.

This was a practical necessity, as otherwise he would have hardly been briefed at all, having insisted upon setting out straightaway. (Strange how he was being allowed to insist upon this and that…) But before long her voice faded, suffocated by bestial transmissions from the radio-emitting denizens of the forest.

By that time, however, Gengr had learned enough to be able to inform the men under his command: “We’re tracking nine convicts. To have made this trail, a good number of them at least must be armed. We have reason to believe, in fact,” he spoke over his shoulder between swipes of the sponnd-blade, “that they all are. They impersonated Stormguard personnel and got their hands on Stormguard weapons – that’s how they got out. Must have been long planned.” He spoke on, giving more circumstantial details of the business, in the vague hope that this would enhance his status with his dubious followers.

“Well, zamur G-A,” drawled his second-in-command, Lanok Ryr, his long, mournful face running with sweat as he lifted his sponnd-arm for another swipe at the vegetation, “if we’re ambushed” (he huffed, blowed, swiped) “it could get interesting.”

The exhausting struggle continued through another fifty yards of stem-snapping and burning. “Stop,” Gengr ordered at last. He turned to check that he had been obeyed along the line. “I see bodies.”

Lanok pushed forward to stare, alongside Gengr, at the light of a clearing.

“So it’s happened.” The selfish thought occurred to all: To them, not to us, thank the skies… Here we see one of the infinite ways for luck to run out in Fyaym –

“What do we do now, zamur G-A – bring them back?” asked one of the men.

“Maybe. After we’ve taken our look at what they saw. Is this nyr fully equipped?” asked Gengr loudly, turning to face his group.

Lanok Ryr curtly assured him, “It is.”

As he led them into the grim clearing, Gengr noted that it was bare of vegetation because it was bare of soil; floored with slippery rock, it possibly comprised the ice-polished peak of a mountain whose base lay miles deep in Ooranye’s frozen mantle.

Scattered over this bleak surface were the torn bodies of nine men, whose escape from prison had won them so brief an hour of liberty.

In silence the twelve men of the nyr gazed at the pathetic sight. Gengr could guess what the men were thinking with regard to himself. This, O foreigner, is Fyaym; here, O Syoomean, death comes from nowhere, in intensity of mystery, and how can you expect to deal with such? How can we be expected to trust and follow you? Go back, you’d better, and seek some safe employment in the city; your status as a mascot makes you popular there.

He had seen insubordination coming. During the toilsome march through the forest it had incubated in the expression of Lanok Ryr, more shuttered with every yard of progress. A flare of intuition now illuminated to Gengr the full extent of the danger he was in –

If his men did not trust him, he was likely to be in peril from them, precisely because no legal means existed to depose an incompetent commander. If, in other words, they thought he must go, then something unrecorded would have to happen. And nobody would ask too many questions afterwards, if the unrecorded thing was done “in a Fyayman situation”.

Fortunately there was a way out. He could satisfy their requirements: he could be competent.

For a start, the shrewdest move he could make would be to take upon himself the next on the list of jobs to be done.

“Time to read,” he announced, pointing at a corpse which had an undamaged head. “Looks un-minced, that one. Now, who’s been lugging the gear? You, Hyv Slarr? Set it up before the meat grows cold.” His ghoulish bluntness went down well. It was certainly appropriate for the business he must now undertake – that of recording into one’s own mind the last thoughts of a person who had died by violence.

One might see, hear or feel almost anything. The less sentiment, the better.

While most of the nyr kept watch, Gengr squatted beside the selected cadaver. The atrocious procedure was set in train. Hyv Slarr wired the crystals of the psych-scanner between the corpse’s head and that of his commander. The last thing Gengr saw, before his vision blurred, was Lanok Ryr’s expression – now fluid with unease.

Then came the shifting blur and the moments of double vision during which Gengr’s mental reflexes tried to resist the influx of another’s memory. After that short struggle, something within him surrendered. His own sight and hearing had gone. It was as if he had entered another’s dream. He was this other person. In that role he was startled, he was glancing up to see things that looked like – what?

Like living rags launching themselves from the treetops. From their exaggerated mouths dribbled a screech, a blubbery sound, while membranes extending between their four outstretched limbs. He saw taut corners adorned with grasping claws –

It all amounted, fortunately, to a very short dream. Gengr barely had time to forestall its end, to rip the crystals from his forehead before the vision collapsed in final darkness.

He had cut it fine. Even by proxy it would not do to experience that ultimate full stop; his own heart and brain might well have shut down in sympathy.

Lanok Ryr stood over him anxiously as he repeated, “Zamur G-A, what did you see? Answer me. What did you see?”

“What? Yes, it’s my memory now,” reflected Gengr, shaking. “Um, what did I see? These men were killed by tree-dwellers. Kite-shaped things. Glided down, ripped the men to death. Claws, teeth.”

“Intelligent creatures?” asked Lanok, scanning the canopy above.

“How should I know?” Gengr scrambled to his feet. “Let’s hope not.” Like the others he could not help repeatedly craning his neck. But the opaque green cover which towered around the edges of the clearing showed no motion now. “Might make little difference.” He sensed some approval of his words.

Under the circumstances there was no question of bringing the bodies back or of taking the time to bury them. Gengr ordered holographs to be taken of the scene, recording the wounds on the corpses; then he rallied the nyr: “We have done all we can do here. Our duty now is to get back alive with what we know, such as it is.”

Lanok Ryr said, “This is Fyaym. We have done well enough.”

Gengr eyed him with some appreciation of those fatalistic words: This is Fyaym. In every culture and period, it was a condition of survival not to expect too much; the untameable lands punished the arrogance of those who sought to understand. Uranians born tens of thousands of miles and millions of days apart shared that reflexive shrug, This is Fyaym.

Through the swaying stems, the sail-size dangling leaves and the pummelling branches, they pushed back along the trail, which was fast disappearing, overgrown minute by minute.

Gengr panted, “At least we now have plenty of cover.”

Lanok replied, “Yes, we’re certainly safe from the upper canopy. But if they’re intelligent, zamur G-A, they may have other methods of attack.”

“You think they are intelligent.”

“They didn’t eat the men.”

“Proves nothing. Dumb brutes can kill for other reasons than food. Defending territory.”

“Doesn’t matter, as you yourself suggested. Reckon the Worm’s behind it, any way you look.”

Worm? It was the tone in which it was said: as though everybody was supposed to know of the thing. Gengr had a hunch that he would do best to guard his tongue for the moment. He remained close-mouthed until they had won through safely to the city’s perimeter.

Officials met them at the gate. “Well?” asked one.

Gengr now experimented by saying, levelly, “The Worm.”

Peculiar… it seemed to be enough! Nobody asked what he meant! He and his company were let by without further questioning.

Shortly after that, he was in conference with old Noad Reyeb Lalldorpl and Daon Polange Nsef in a chamber in the Palace of the Noad. While Lalldorpl reviewed the recorded evidence, Gengr sat back in eerie comfort, ironically glancing at the magnificent potted plants which decorated various stands. Dizzy transitions from the perils of outside to the haven of a city were a commonplace of life, so why should he be feeling that in a sense he had not left the jungle?

The Noad was speaking to his designated heir, “The original breakout shows, of course, that the Worm can inspire and incite the inmates of your prison even through its walls.”

The Daon formally replied, “It would seem so, Noad R-L.”

“A serious development, do you not agree?”

“Undoubtedly,” she agreed in a bleak voice. Having uttered this admission, Polange Nsef was left in silence for some seconds, and Gengr guessed that she was being “left to stew”, but her next words sounded un-embarrassed. She merely mused, “And maybe, it is coiling at us from another direction also.”

The Noad growled, “Go on, Daon P-N.”

“Those kite-creatures that killed our people: it is the first report we have had of hostilities from that particular species. So we have to ask, is the Worm training new species in the forest, or –”

“Or,” the Noad finished for her, “is the Worm bringing new species to the forest?”

Then both of them turned to Gengr, perhaps because they had sensed him stirring in his armchair. “Give us your opinion, zamur G-A,” the Noad invited.

How in the name of all the skies can I possibly give an opinion? “As a foreigner, recently arrived,” he evaded, “I have no idea what strategy this city ought to pursue.”

“Come now, Gengr,” said Polange with a kindly smile, so that the mere fact of being addressed by her in company was felt by him to be a special promotion, “you have one successful expedition under your belt – enough to make you one of us.”

Much happened to Gengr in that instant. Polange Nsef had figuratively set him on his feet. Basking in her warmth without being intoxicated by it, Gengr could now reflect that his jaunt to the forest had at any rate gained him one undoubted benefit: it had allowed his sanity to be restored as far as his attitude to her was concerned, because, in gaining a bit of proper status of his own, he now found it possible to throw off the illusion that any one person can be of all-engrossing importance – or that one’s conversations with such a person need be perfect. As a result he actually felt still warmer towards her. Closer, too. He was able to love her ordinarily. That was far better than languishing in helpless worship. Wonderful how this development cleared the head.

He remarked: “I suppose that your unfortunate escapers had every motive to take the risk they did. Far worse than death, far more to be feared, is loss of liberty. That alone is enough to explain their crazy dash out into the jungle.”

It was his little offering, his attempt to make sense of recent events. But it fell flat.

He could see in their faces that they did not believe it was enough. The Worm, the Worm’s to blame. And the ignorant foreigner Gengr Axtain, sensing their reaction, was then glad that he had refrained from expressing his doubts about this Worm – though he feared that with every minute that passed his admission of ignorance would become more fraught with risk. Yes, the longer he left it, the more embarrassing the prospect of having to confess that he did not know what they were talking about –

Fortunately, however, the old Noad sensed his predicament, and deigned to impart some illumination to the baffled Contahlan.

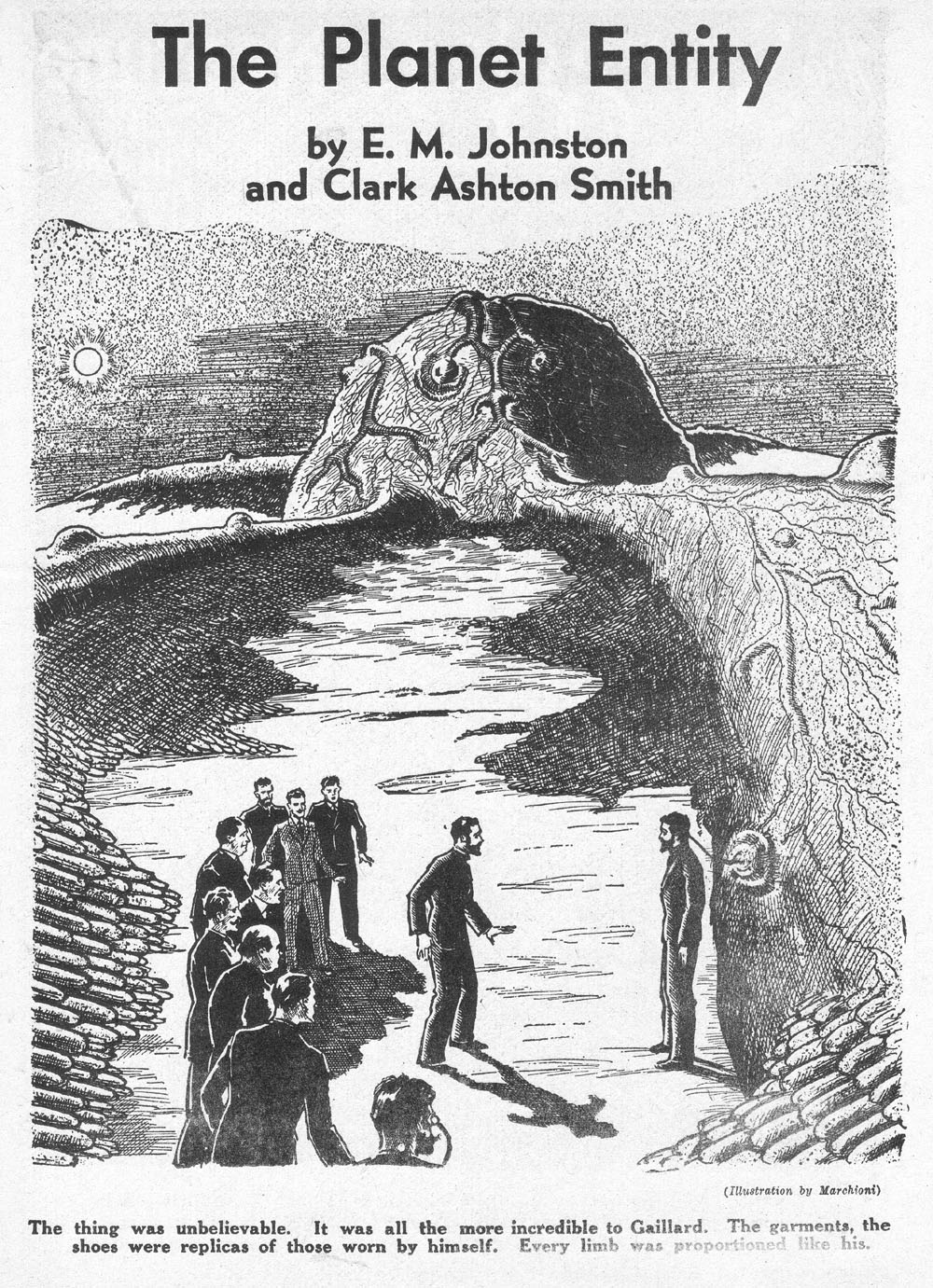

“Our scientists and philosophers,” he explained, “tell us of an agglomeration of souls which seeks to draw others into itself. Technically it can be described as a four-dimensional Worm expanding through history.”

I can’t get drawn in any further to this crazy rubbish – Gengr suddenly decided – without at least making some sort of stand.

“With all due respect to your savants, can you be certain that it is real?” he asked as politely as he could.

“It is real. The question is not ‘if’ but ‘when’ it will slither forth to attack us again.”

“Forgive me for insisting on clarifying this point – but you are talking, are you, about a real physically harmful attack by souls?”

The Noad said placidly, “All attackers have souls.”

“I see,” said Gengr. Perhaps it did not matter whether he believed the old man or not. Either the Worm, as inspirer, existed, or it did not – but the attacks ascribed to it did obviously exist, and, from that point of view, the towers of a city were just as likely as the boles of a forest to count as the jungle in which such a Worm might hide.

The Noad continued, “And you, Gengr Axtain, being stranded here, must throw in your lot with us.”

Gengr almost shook his head, not because he was about to say “no” but because he already felt the clinging force of these people’s ridiculous beliefs. Worm, for skies’ sake! Outpost folk, stranded out here for aeons, might understandably develop their own quaint notions. But when said notions threatened to climb into his head –

But he had better pull himself together and reply. You can’t not reply when the Noad has just spoken about you ‘throwing in your lot’.

“Of course I understand that I must now be a true Polevan till the day I die, Noad R-L.”

“Thank you, zamur G-A.”

His citizenship was off to a good start.

4: War on the Worm

Gengr found the men of his nyr still waiting for him as he emerged from the palace into the street. They greeted him respectfully – they were in favour of him now – but he had no immediate use for the group. So he dismissed them with thanks, promising to call on them when he needed them. As they dispersed, he became aware of a figure leaning on a pillar close by.

The figure then strode out from where he had been waiting, and Gengr recognized the tall, heavy presence of Nekkon Lalldorpl.

Sharp shadows are rare on Ooranye. Most of the daylight is diffused by the innate glow of the air itself; how then did this son of the Noad seem to cloak himself in a clean cut shadow? An impression of mood, that must be all… Gengr tried to dismiss his feeling of revulsion.

Nekkon demanded, “Are you ready to fight the Worm, zamur G-A?”

“I am ready to do what Noad Reyeb expects of me.”

“Yes, but the Worm –”

“I am ready,” repeated Gengr, rendered snappish.

“Hrrmm,” said the Noad’s son. “That’s more than any of us can say.”

Sure, now, that he was being needled, Gengr felt in better humour, telling himself that this encounter was quite ordinary, Nekkon’s resentment quite understandable. Mere natural jealousy, caused by the popularity of a foreign mascot. Nekkon was no doubt already frustrated enough, barred as he was by iron-hard custom from the succession to the noadex. Well, it would do no harm to offer some modest concession to the fellow’s pride.

“What I am ready for,” Gengr drily conceded, “is, at most, to look good trying.”

“Ah,” said Nekkon in a tone that laid a silken fuse, “so you do not believe that you will do us any real good?”

“Probably not.”

Gazing into the Contahlan’s face, Nekkon was taken over by another of his domineering twitches. “Aaarrrrr,” he breathed, and announced in a voice that rang:

“For as long as people are not swerved from their resistance to the Worm by an interloper who lacks their knowledge in his blood – for just so long will you, Gengr Axtain, enjoy a full life here in Poleva.”

And he stalked away.

Gengr reflexively sought to square his shoulders but felt enfeebled by perplexity: what was worrying that peculiar and discourteous man? Surely, in this place, maintenance of belief in the Worm appeared to be no problem. Scepticism was non-existent, apparently. So why had Nekkon lost his cool?

During the next few days Gengr kept his ears well open and simply confirmed his opinion that belief in the Worm was pervasive and unstoppable – certainly in no danger of losing credence through any remark of his. He became educated in how the idea perpetuated itself. Any elongation of any tale of woe was counted as a wriggle of the Worm. For example the forest glade, where the Kites had attacked the fleeing convicts, had previously been the scene of a different attack, a few lifetimes ago, by an entirely different species upon another party of explorers. Coincidence? Never! It was the Worm stretching its coils across time and across many a situational divide. Far-fetched, yes, but who am I, Gengr Axtain, to argue about what could or could not happen here?

He went along with it all. No doubt by the end of his life he would have learned wholeheartedly to share in the beliefs of the Polevans. Already he found that he respected them. Only if by some miracle he could return to Syoom, could he ever despise the memory of such superstition. Here, the local way of thought was bound to take hold; you couldn’t reasonably expect Fyayman outposters to think like Syoomeans. In fact you could call it reasonable, here, that in their yearning for order the Polevans should prefer to blame one unified Worm for their plight, rather than an infinity of perils.

Besides, ultimately what difference did it make what you called things?

All in all, life was being good to Gengr. He had been given a home in a city he liked, inhabited by a people he liked and who liked him. The prospect of action enticed him, and if his next adventure had to originate in some bizarre fixation with a hypothetical four-dimensional Worm, so be it.

If anything disturbed him these days, it was the off-putting post of prison warden held by the woman he loved. What a saddening twist of fate: the gentle Polange as a denier of liberty. Someone had to do it, of course, but why did it have to be she? But – here a useful sadness – his distaste for her occupation was going to make it easier for him to ration his time with her. He would limit his visits, lessening the danger that she might get tired of him before he could win a proper position for himself.

For ten days Gengr wandered the Polevan walkways, rambled around the city and lounged in the parks, listening, observing, learning; trying to identify those facts which a native finds familiar but which may take an immigrant a painfully long time to absorb. In order to be useful he must become attuned to the cultural environment while at the same time retaining his own Syoomean heritage – the one thing that made him special here, the perspective which he had brought as a gift to his new home.

It was the mid-day hour; he was striding confidently down a ramp into the vaults of Poleva. His view of the cityscape steadily shrank as he descended into the subway which led to that much-thronged basement world of corridors, repositories, archives and maintenance machines called, generically, “the vaults” of a Uranian city. In the cavernous volume around him, no lamps were necessary; the airglow itself allowed him to read expressions on the crowded ramp when the sudden electrifying announcement blared over loudspeaker:

“Polevans! This is Nekkon Lalldorpl, speaking for the Noad, to tell you that our wayfarers have detected the approach of a hostile expeditionary force from Nusun. The Noad has given the order for our forces to mobilize in response. He has given me the field command: my rank is now omzyr of all Polevan armed forces. Citizens, this is our opportunity to hit back at the Worm! This time it has blundered – has donned a disguise too cumbersome to escape our vengeance – and our Noad has authorised me to proclaim a zemmg against this Nusunian army. An unstoppable zemmg which will end only when our aim is accomplished. Death to the Worm! Officers will report to me by noon tomorrow.”

The loudspeakers fell silent.

People were shouting, cheering the zemmg, congregating to discuss the news – and what crazy news it was! How, wondered Gengr, could one Fyayman outpost invade another, and why should it try? On the other hand – how great to hear a zemmg proclaimed, not just an ordinary war-effort but a collective exaltation, such as now he saw taking hold in the faces around him. They were lit up with zeal as if already promoting those souls who would soon be lost in battle. Try to keep calm, Gengr told himself. Remember a zemmg is hedged about with tradition. It must not be proclaimed frequently lest the notion be devalued. One must always check, always make sure: was the occasion serious enough? Apparently this time it was, to judge not only from the enthusiasm but also from the hard-headed talk around him. “This invasion,” somebody asked, “is it a mass-migration?” “Could be.” “The only way to cross Fyaym is to do it in force,” someone else opined. “Wonder why it was announced by Nekkon and not by the Noad himself?” “The Noad must be unwell.” “Sudden, isn’t it?”

Gengr meanwhile, regaining his original purpose, pressed on down into the vaults. He had his own quarry and he must not lose sight of it…

He continued along an underground thoroughfare until he entered a series of side-corridors, each smaller than the last, which brought him at last to a lonely room with a desk and lamp. The desk had a transparent top, like a display case. Under it was a sheet of lettering, lit to reveal one of the historical records of Poleva.

That moment when eyes and text faced one another was the true call to arms for Gengr Axtain. In particular what kindled the fire in his brain was a message latent in the innocent list of regnal data:

2259th Noad: Brenbl Lalldorpl: 3,622,710 Nb – 3,628,786 Nb

2260th Noad: Kren Yound: 3,628,786 Nb – 3,629,225 Nb

2261st Noad: Norpay Lalldorpl: 3,629,225 Nb – 3,640,576 Nb

2262nd Noad: Operlwa Pyon: 3,640,576 Nb – 3,640,800 Nb

2263rd Noad: Reyeb Lalldorpl: 3,640,800 Nb –

Could other see what he saw in these names and dates?

The facts in this Noad-list were hardly a secret! And no-one else had yet drawn any dire conclusion from it, so it must certainly be too soon for a recent immigrant like himself to issue a public warning.

He must gather firmer evidence. Besides, he was in a state of some confusion himself. He suspected an enormous crime but could as yet imagine no motive.

At this rate he’d soon be a firm believer in the Worm!

Be that as it may, his adopted city was at war and invasion was imminent. The zemmg throbbed in his mind. It was warning him not to play the detective today; he had a nyr to lead, and fighting must come first.

…The encampment outside Poleva, which Gengr and the eleven men of his nyr joined the next day, was awash with the din of a mustering force of fifteen to sixteen thousand sponndarou, each laser-armed warrior crackling with eagerness to get at the enemy. Subliminally the zemmg was in full blast, the summons to enthusiasm thrumming along the nerves and chanting in the mind’s ear so that one was forced to believe in victory. Gengr Axtain, as he made his way among billowing cloaks towards the Noad’s command-post, experienced a sensation of wading as if through a shallow sea that rippled around him, in the midst of which his destination rose as an island: the pyramidal platform from which the Noad and the omzyr and their staff could survey all the formations and sub-formations of the swirling encampment. Gengr reached the foot of the command-post. He began to mount the ramp.

In one direction twinkled the forest, while in another the serrated Badlands stretched to the horizon. Their succession of naked brown ridges were moderately smeared with dark blue ice. Surrounding all of this the loamland gralm – the great world plain, the solid ocean of Ooranye – must widen beyond the horizon’s curve.

A voice welcomed him: “Ah, it’s Gengr the Syoomean, here to contribute his counsel.” It was the voice of Noad Reyeb Lalldorpl himself. He and his son, the omzyr, stood in a cluster of the principal zynzyrs. Next to this group was a canopy supported by four white poles. Underneath that, resting on a table, lay the city’s most treasured possession: a priceless banessyen – a moving-map.

The figurative carpet of welcome rolled out for Gengr Axtain, as hands beckoned and smiles drew him forward. As an officer, he had already reported for ordinary military duty to omzyr Nekkon, but this was different. Playing the part which he now understood, the role of an exotic Syoomean banner that waved over their campaign, Gengr spoke some suitable words to the Noad and his advisers and chief officers. The top-ranking zynzyrs listened respectfully to such statements of the obvious as, “If the enemy has any sense, he’ll approach through the badlands.” Would they also listen to something more urgent?

The old Noad was speaking to him again.

“Something still bothers you, zamur G-A.”

The group of advisers was dissolving, each zynzyr leaving to take his place in the final formation. They were due to set out within minutes; the banessyen was lifted off its stand, for a moving-map must be borne away in the midst of the departing host… Gengr meanwhile, to his relief, was being given a chance to exchange a few private words with the Noad, whose son, the omzyr, had now departed from the platform.

From close up, Reyeb Lalldorpl looked drained. Small wonder that the actual field command had been given to a younger man. Even as matters stood it was the most that the Noad could do to bear up under the relentless cheerfulness and pride of the zemmg, which gouged through them all as a fast river gouges a hill.

“I was, er, concerned about numbers,” Gengr began.

“Fifteen thousand,” waved the Noad. “Out of a total population of a mere one hundred thousand, and at short notice – we have done well, I think.”

“Too well, perhaps.” Gengr’s voice of realism struggled to be overheard against the continual thrum of confidence in both their minds. “The city is being left depleted…”

“Tell me more –” Reyeb Lalldorpl flung out his arms – “or ask me more – ask me where in all that wasteland Nekkon thinks he will aim our force, and why we are not simply waiting here for the enemy’s attack. He wants to carry the battle to them, so out we go.”

“A risk,” nodded Gengr.

“To be fair,” shrugged Reyeb, “so is the alternative. And my son is more of a fighter than I am.” The Noad smiled tiredly and his arms flopped to his sides. All of a sudden he and Gengr stood in a bubble of relative calm for the thrum of the zemmg became muted on the deserted platform, as the army began to recede from the pyramid’s base.

Now, thought Gengr, was his oppoprtunity to confess his real unease to the Noad. Unease concerning the man’s own family –

Impolitic or no, I must take the plunge. He explained, quickly, what he had noticed in the Archives.

“Ah,” smiled Reyeb, “so you looked at the Noad-list. The Lalldorpl-list, as one might call it, ha-ha! Yes, I don’t mind admitting, some of us were tyrants in the past. Poleva has had its fits of arelk, and may have them again one day… but rest assured, I have kept good watch for signs of it in my time.”

Arelk – the political “hardening of the arteries” – was, in truth, absent at the moment from Poleva. Gengr would have sniffed it ere now if it had been present. Since it was not, his condemnation would have to wait. And in any case where could he find the audacity to voice criticisms in front of this charming old ruler whose good-humoured sincerity was so transparent? The civilized honest voice, quite prepared to admit past wrongs, was so much more effective at silencing Gengr, than a peremptory command to cease discussion would have been. So the immigrant from Syoom did not have the impertinence to push his luck any further.

He took his leave of the Noad, looking back just once. Reyeb Lalldorpl was leaning on the empty map-stand, gazing at the departing host of his people, his worn-out face wearing that serene smile which says “it is all out of my hands now”. Gengr descended to ground level and went back to his nyr.

His duty now was not to think deep thoughts but to stride about and issue orders, to manoeuvre his unit into correct position within its nyzyr. During minutes of local standstill, while other units changed places around them, he made sure that his men checked their gear thoroughly, as they were carrying much more than usual on an expedition. Their cloak-pouches did not suffice; they had to wear packs.

“Polevans!” came another blare from the loudspeakers. The men looked up to see the tall, heavy figure of their leader who stood on a wheeled platform well away from the command post which the Noad had used. “Warriors! Invicible-souled zemmgars! I call you forth to fight the Worm at last! That same Worm which, after so many blows struck against us, has finally poured itself into the form of a Nusunian army which – thank the skies – we can hit. This physical enemy has been winding towards us for the past few days through yonder ridged terrain, and we can trap it there! We all know, do we not, that the Worm never abandons its form until the next blow has been struck: so we need not fear any shift of identity before we crush it. Fate has gifted us an opportunity which may never recur. This is why I judge it worth the risk to lead you all on foot into country which is impassable by skimmers; into a barren land where we must carry all our provisions, but where the enemy must suffer the same disadvantages as we. An enemy of flesh and blood, whom we can beat. So, forward, Polevans, to your best-ever chance of victory over the entrapped Worm!”

Other, similar exhortations were given out at intervals of a few hours.

The units poured over the edge of the near canyon and soon the men’s boots were crunching along a rubble-strewn path between inhospitable slopes. That evening, they bivouacked on a plateau between two gorges, still in sight of their now-distant city. Poleva had dwindled to a toy-sized coloured egg. The next evening, they could no longer see it at all. However, they could never be lost, so long as they retained the banessyen. The moving-map was guarded personally by omzyr Nekkon Lalldorpl.

Gengr was summoned by the omzyr for consultation in the evenings. In his own opinion he contributed little of substance to the discussion. Yet (so he was repeatedly told) the mere fact of his participation had a helpful effect upon the morale of the troops, who were bound to be impressed at the thought of a real Syoomean presence at the councils of war. It was the same old story, rather sad in a way: being valued for what one symbolized, rather than as an individual.

But it was also good luck, for he got to see the banessyen.

The very thought of this priceless object being taken outside the city’s defences might have sown deep anxiety among the people, were it not for the continual thrum of the zemmg, the steady exaltation keeping the army more confident than it would otherwise have been, that the risk was worthwhile. A banessyen was viewed almost as a guarantee of victory, at any rate of defensive victory. According to legend, backed up by archeology, one thousand three hundred and thirty-one of them had originally been made. By now there were only a few score in existence, rare enough for most cities (and a few airships) to possess only one, if any. They came in various designs, the most common being that of a hand-held lenticular object. The ‘sheet’ varieties, which could be unrolled and laid out like ordinary still maps, were the rarest of the rare. The Polevan banessyen was of this special sort. This meant that Gengr could actually stand and pore over it as he would a normal map.

He felt stupendously privileged to be accorded this sight. Even though no big shape was moving on it at the moment, it thrilled him merely to be able to see, on its dark purple background, the stationary fuzz which was the Polevan army encamped, some inches away from the similar-sized fuzz, also stationary, of the Nusunian army. Tempting it was, to try to puzzle out how the map’s dots knew! Futile, to speculate on why those imprisoned dots (a microscopic race, tamed long ages ago by Phosphorus Era savants) should continue to serve as faithfully as ever. Perhaps they had been willingly enthralled. (Or more likely the legends were wrong and the thing was just a clever machine. Legends about the Phosphorus Era never ceased to grow in the telling.) Whatever the case, it was hard to take one’s eyes off the object. Conversely it also took some courage to look at it. The symbols adapted themselves to the user’s emotions – an approaching peril, for example, depicted as a line with white teeth, might suddenly writhe into an unclassifiable shape which communicated terror direct, like a form seen in nightmare. To study a banessyen and to know that its symbols were somehow true was like having one’s fortune told in blobs and moving lines with no choice but to believe.

“What do you notice this time?”

The grate of the voice startled Gengr. Well, his focused gaze had invited the question. He had being eyeing a particular patch on the surface of the banessyen, a patch where the Polevan fuzziness showed a split. It meant that Nekkon had ordered forth a vanguard. To probe for enemy emplacements which might be too small to show up on the moving-map, though the fuzz that denoted the main Nusunian force remained clearly visible.

“Well? What do you think?” insisted Nekkon.

It was as though a Syoomean opinion really had become important this evening.

“Well, the Nusunians…” faltered Gengr, “er, they have started to veer. And they’re slowing their march.”

“And?”

“We have slowed too. I suppose we’re both going to dance around each other for a bit. And then we’ll close in. I guess they have a banessyen too. Either that or their scouts are superb.”

It must have been a sufficient thing to say, for Nekkon grunted and allowed him to go.

That night as Gengr Axtain lay wrapped in his cloak, gradually sinking into sleep with the sense that he had escaped something narrowly, the piquant thought came: if the Worm existed, would it not show up on the banessyen? Would I not see a live portrayal of it there, symbolically squirming? Gengr snickered. He had seen no such shape. Not a trace of one. So much for the Polevan Worm-obsession.

The next day’s march ceased shortly before noon. The zynzyrs had received a halt order from the omzyr. The army had got close to the summit of a windy, gravelly pass. The men removed their packs and sat on them.

As they rested and looked around at the stark horizons, rumours buzzed through the ranks: the omzyr had chosen this place for a stand; the Nusunian army had come into contact with the Polevan vanguard and fighting had begun; the omzyr was taking precautions against a flank attack… Gengr said as little as possible. Quite a few sponndarou asked him what was going on, but all he could think of to reply was, “We shall know soon enough,” – for the first time wondering whether perhaps his own symbolic role might turn out to be more trouble than it was worth, to the authorities. I know I’ve been some use for morale, but I could cause bad trouble for Nekkon, especially if I wanted to.

An officer approached, summoning him to the omzyr. Bystanders nodded meaningly to one another. Gengr felt the eyes of the troops upon him as he rose and walked to the command tent. It was now guarded on either side of the entrance flap by men with lasers drawn.

He stepped in, had time for one glance at the surface of the banessyen –

“I have news for you, Gengr Axtain,” said the omzyr, who was seated with his face turned three-quarters away from the tent entrance, while a noisy wind thumped at the tent walls, punching them inwards. Nekkon Lalldorpl continued quietly, “News flash relayed from Poleva: my father, Noad Reyeb Lalldorpl, died this morning.”

So that was that. One kindly, beneficent ruler was no more. A city was bereft in its hour of need. “Sad news indeed, omzyr N-L,” said Gengr, watching the other’s face.

Nekkon sighed, “I have decided to call off the campaign. The new Noad is going to need the support of all the city’s forces around her. I cannot leave her by herself at this crucial time.” And while he spoke these incredible words, Gengr did nothing but sit and nod at every sentence.

On one level it was astonishing enough: he kept asking himself, what had become of the unstoppable zemmg, the drive to victory, the rousing pledge to go out and fight the enemy? But on another level came a spreading certainty like blood from a deep wound. He must stretch his mind and hide his feelings. At least till he got back to the city. Whereupon he must have his accusation ready. Which meant he must stay alive till then.

“I understand, omzyr N-L,” he said. “You have my full co-operation.”

5: The Worm unmasked

He understood only too well.

As the army pulled back towards Poleva he marched with a burden he could not share. Like a man with an ill-fitting pack he kept trying to rearrange the knowledge. Unfortunately the burden and the weight of decision could not be adjusted to a comfortable fit.

In the confused state of the army, enthusiasm had decayed into mere tension; the men did not know whether they were winning or losing the war; Gengr for his part no longer cared about the danger from the Nusunians. He was concerned only with the question, how much of what he himself now knew might be suspected by Nekkon Lalldorpl. To play safe would entail going into hiding as soon as they reached the city. On the other hand that might be the worst move to make. Perhaps at all costs stay public, surround oneself with witnesses, sleep in the dormitory of a public hostel…

In the end, when the army filed back into the city and the air buzzed with cries of reunion, Gengr simply went alone to his assigned dwelling. He would trust, for one night at least, that Nekkon believed in his continued usefulness.

Exhausted, he lay on his bed. One moment his cheek was on the pillow and his drooping eyes caught a last fading sight of the lush curtains covering the window, as his mind spiralled down into sleep – then he found himself suddenly vertical, flicking those curtains aside, and, due to the excellent travel facilities of dream, looking out upon a scene far, far from Poleva.

It was a scene that blasted him with such yearning that he almost doubled up with homesickness. Yet the place was one which he had only seen twice before in his entire life: the foamscape of Ammye, in central Syoom. Rising in the midst of the foam was the glorious double-tiered disc of Skyyon.

The sunward polar city stood tall and proud on its glittering wineglass stem; stately airships and swarming skimmers clouded its aerial hangars and docks; from the midst of the upper reaches rose the Zairm, the Sunnoad’s Palace, like a solid waterspout or flame that whipped eternally towards the pointlike zenith Sun.

The sight, though awesome, was as familiar as if he had lived in that palace as a child. Dreaming, he accepted this familiarity without question. Indeed there was no need to puzzle over it, for here was the centre of Syoom and it was Syoom that he wanted and needed… He moved forward. He drifted through the palace walls. Like a thirsty ghost he sipped at that sense of belonging, he truly believed that he was really there… even if it were but a dream; for did not the act of thinking about a place mean that one’s mind was there? Anyhow the place itself did really exist, and his soul belonged in it, here at the sunward pole of Ooranye. Next his mind fluttered specifically towards the Sunnoad’s throne. More real than real life, the dream’s lemon-gold became the colour of knowing. This was the key awareness, awareness of the worth of what one saw. No force of gravity could pull so hard.

The palace, he knew, was built of smollk, the foamed ore of Ammye; the pumicelike segments had accumulated age by age, till the Zairm was the size of a small mountain, rising from the upper platform of a still vaster city. Gengr viewed all of it simultaneously, being, in dream fashion, somehow both inside and outside the great structure. The crust of memory was thick. It reached across a geological age in the throne-room, Zdinth Hall. Admittedly the succession of Sunnoads had sometimes been interrupted, but the traditions of the office had never been forgotten.

Traditions – their weight and power – were what he was going to need after he had awoken.

And that thought reminded him, alas, that this marvellous place was in actual fact not really around him; it was unattainably distant because THIS WAS ONLY A DREAM. He snatched at it as it began to fade. Snatch at a glow? Pathetically he zoomed around, trying to “drink” Zdinth Hall as though it were nectar, to grab what could not be grabbed. But suddenly, in reprieve from the gathering goodbye, the scene brightened one last time, as a hero strode into the hall.

The hero was a tall erect wayfarer who advanced between lines of notables towards the throne. Gengr lost no time in merging his own viewpoint with this man so that now he was the tough and successful character; none other, in fact, than the famous Rezram Pamek, who brought vital information for the Sunnoad during the Vrar Crisis of sixty or so lifetimes ago: Pamek, bringing knowledge of the whereabouts of the enemy’s lair…

The viewpoint changed again.

The dream’s atmosphere turned grumbly, became curtained with dissatisfaction as reverence fell away from the hero and the dream-ego reverted to a separate, critical Gengr Axtain who spoke out: it was all right for him. But how am I to do that sort of thing here?

The dream snapped and curled away like cut tape.

He awoke, feeling desolate.